Native, Foreign, Hybrid

Los Angeles, garden city

Angela Blake

Los Angeles is not usually thought of as a city of gardens. “The gardens of Los Angeles” sounds as counterintuitive as “the ski lodges of Miami.” But in fact it is the number of trees that first surprises the newcomers as they descend toward the runways of LAX, and the scent of some unknown blossom that can confuse those who leave their windows open as they traverse the city. Los Angeles is a city of gardens, a horticultural cornucopia instigated in the late nineteenth century when the design and planting of gardens shaped a landscape that—at least in the eyes of the city’s new Anglo settlers—was undefined, nameless. The story of the city’s landscaping can, like other L.A. stories, be interpreted as a narrative of racial hierarchies, conspicuous consumption, and the fantasies of out-of-towners.

If you go in search of L.A. gardens today, you’re likely to eventually end up in the grounds of the Huntington Library, located in San Marino, an elite enclave next door to Pasadena. Railroad magnate Henry E. Huntington was one of the foremost shapers of L.A.’s turn-of-the-century landscape, and a key player in the city’s Anglo power structure. Huntington, whose Pacific Electric Railroad cars spanned the nascent metropolis, purchased a large Pasadena ranch in 1903. He delighted in his new property, splendidly situated both to see and be seen, framed by the San Gabriel Mountains behind and the still-forming city below. Pasadena, a community formed in 1875 by a group of Indiana residents tired of the Midwestern winters and eager to start anew in the “land of sunshine,” soon became home both to wealthy winter sojourners from the East (of which Huntington was one) and to upper-middle-class weather refugees like the initial band of pioneering Hoosiers. Other Anglo settlers from the Midwest and East Coast repeated this pattern of settlement throughout L.A. and other parts of Southern California. Booster pamphlets and real estate ads depicted lush orange groves, snow-capped mountains, and neat single-family homes nestled in the hybrid gardens that would come to define L.A.’s horticultural landscape: unequal parts English cottage garden, Spanish hacienda, Italian villa, and gaudy perennial flower show. Just add water and stir.

Such Los Angeles gardens played an important role in constructing a regional identity for Southern California in the early twentieth century. Both elite and upper-middle-class garden owners aimed for a sumptuous garden display, preferably including exotic plants such as palms, cacti, decorative citrus, and a year-round floral display, signaling not only wealth and status but also an active appreciation of “the Southland’s” climate. Although there were certainly large and impressive gardens in the estates of the East Coast’s wealthier citizens, Southern California’s much-touted climate—referred to by boosters sometimes as “Mediterranean,” sometimes as “semi-tropical”—made the outdoor display of wealth more important than it was back East. With parties and other social occasions happily spilling outdoors most of the year, the Southern California garden frequently functioned as a key space of social capital to a greater extent than gardens could in the season-bound climate of the Northeast. Nursery owners, amateur gardeners, and landscape architects, as well as elite garden owners such as Huntington, all contributed to Southern California’s image as a horticultural Eden through their enthusiastic experiments with an extensive range of plants.

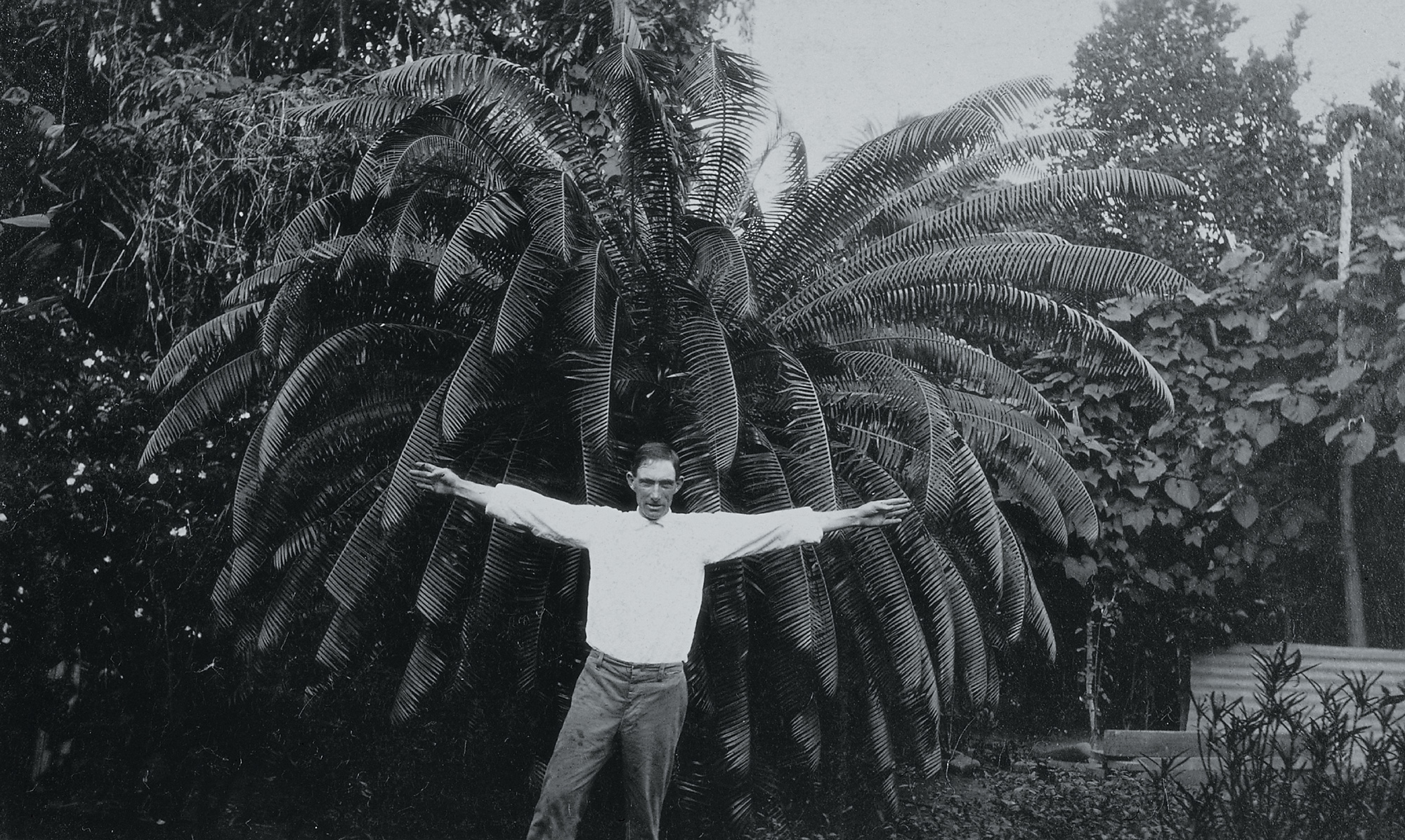

As Huntington’s house neared completion in February 1909, he and his architect, Myron Hunt, discussed the possibility of constructing an Italian garden in front of the terrace, the major southern vista. Despite the fact that such a garden might have worked quite well with the Italianate villa Hunt had constructed, for some reason Huntington soon questioned these plans. When Huntington’s landscape gardener, William Hertrich, weighed in on the matter, he made the case for collecting cycads, a relatively rare semi-tropical plant, which he said would make an excellent landscaping feature. Hertrich sent Huntington a list of cycads available from one of the major American commercial nurseries dealing in exotic plant material, W.A. Manda’s Universal Horticultural Establishment, based in the not-so-exotic location of South Orange, New Jersey. Hertrich piqued his employer’s desire for distinction by pronouncing that the acquisition of such a collection “would be of more fame than any Italian garden.”[1]

Anyone could have an Italian garden, Hertrich suggested. And he was right, at least concerning his employer’s peer group: The fashion for Italian gardens was well established by 1909 throughout the private estate gardens of the United States, and became one of the dominant garden styles in Southern California. Huntington took his landscape gardener’s advice and bought the cycads from the New Jersey nursery at a cost of over $4,800. Throughout the 1910s, Huntington competed fiercely with other wealthy L.A. garden owners to assemble the most extensive and comprehensive collection of cycads. In September 1913, Hertrich gleefully wrote to Huntington about his purchase of a large collection of rare cycads: “I am pleased to tell you that I bought the Bradbury collection of plants for $8,000 and I am very proud of them. Some of them are the finest in existence and others only have one duplicate which is found in Kue [sic] Garden, England.” Second only to Hertrich’s pleasure at obtaining the plants was that of thwarting a Los Angeles competitor in plant collecting, millionaire oil man Edward Doheny. In that same letter Hertrich told Huntington how Mr. and Mrs. Doheny and a local nurseryman, “pretending to know all about plants,” had gone to inspect Bradbury’s cycads. “None of the three had ever seen plants of that kind before nor did they know the value of them.” By a mixture of finagling and sheer luck, Hertrich managed to beat Doheny to the purchase and negotiate a lower price than that offered to his competitor.

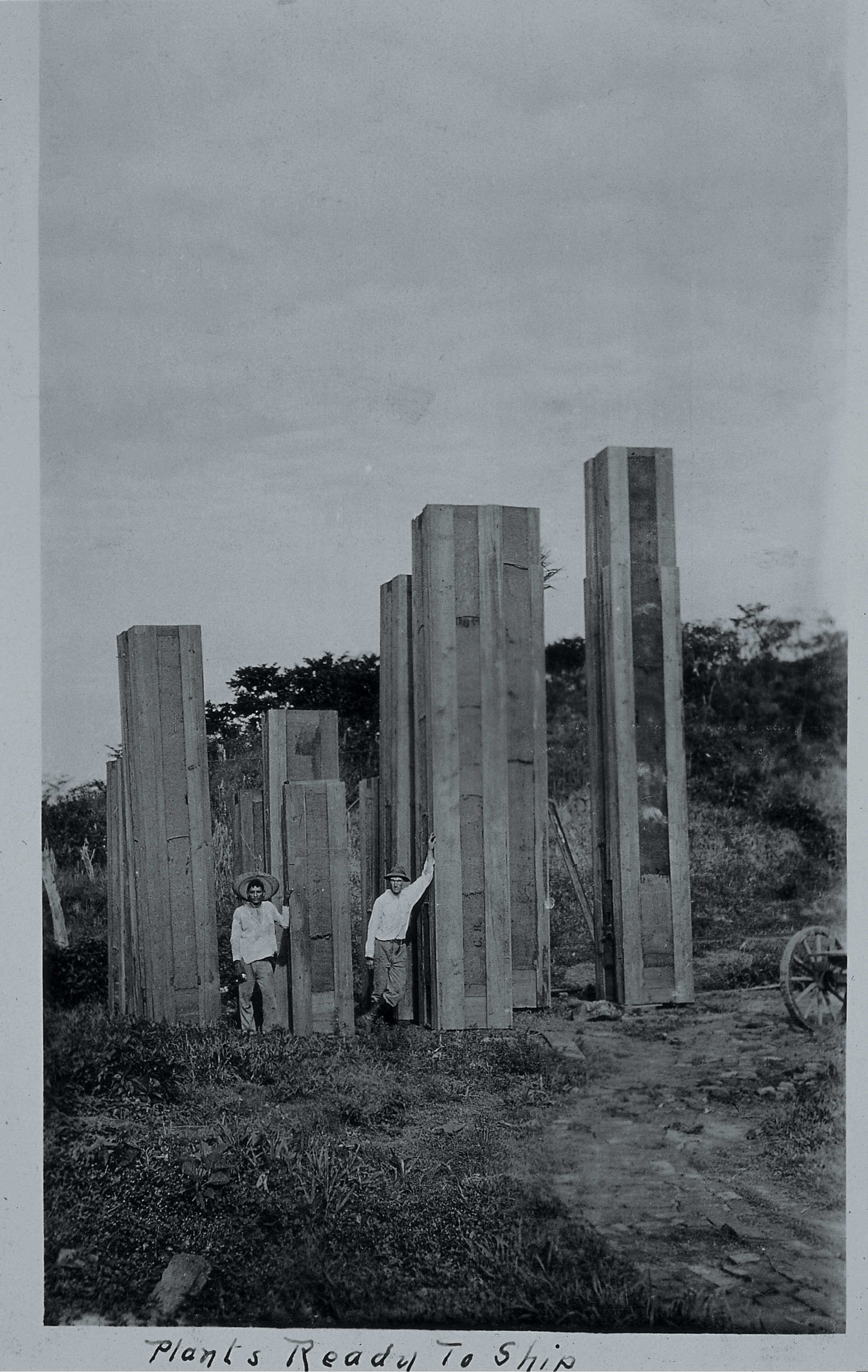

The cycad was the ideal collectible for those elite but anxiously nouveau riche garden owners wishing to demonstrate not only wealth but taste. The cycad, most closely related to the fern but often mistaken for a member of the palm family, is a species of plant found in the southern parts of the Western hemisphere (e.g. southern Mexico, Central America, and Chile) and in the Eastern hemisphere in Japan, New Zealand, and Australia. The collectability of the cycad in part rested in the fact that the plants could so easily be mistaken for something less rare. A cycad’s value and rarity was not obvious to the untrained eye. The thrill of owning such plants was undoubtedly increased by making the owner a possessor of a secret knowledge, poised at any moment to display his erudition in the face of others’ ignorance. Cycads, certainly during the years when Huntington and other L.A. powerbrokers like Doheny were collecting them, rarely came on the market. The New Jersey and Bradbury purchases were rare US opportunities. When they did turn up, the sales most commonly occurred in European markets. A third option, certainly for wealthy collectors, entailed hiring a specialist plant “hunter” to go in search of cycads, then complete the laborious and expensive process of digging them up, packing them in crates, hauling them overland, and shipping them to the US.

The cycad worked as a carrier of one notion of regional identity held dear by the city’s Anglo settlers: that Los Angeles was a semi-tropical region in which thick, lush vegetation should and would fill their gardens and line their streets. This imagined semi-tropical landscape brought to mind images of Eden—an ideal garden in which the very first “settlers” frolicked naked and picked fruit off the trees ... only this new Eden would have a happier ending for the fruit pickers. Furthermore, the idea that the region was only semi-tropical belied any fears that L.A. would offer too enervating a climate. Anglo settlers wanted warmth, sunshine, fecundity, and varied vegetation to please the eye, but they did not want to suffer the fate rumored to befall Europeans in a truly tropical climate—the loss of energy and vigor, the stupor induced by steamy heat, and the sight of half-clad “native” bodies.

The regions in which plants such as cycads grew wild generally enjoyed regular and significant amounts of rainfall and a warm, humid climate. One of the problems with the idea of Los Angeles as a semi-tropical region was that such a notion was simply inaccurate. L.A., with its largely arid climate, could only support semi-tropical transplants by means of intensive irrigation. British writer A.T. Johnson, observing Pasadena gardens in 1913, criticized the use of water-hungry plants: “Look ... into the valleys and plains of California and you will find that they are for three seasons of the year sunburned deserts. ... It is the liberal use of the hose pipe and the garden sprinkler ... that has been the main factor in making the wilderness blossom as the rose.”[2] While Johnson’s alarmist image of “sunburned deserts” should be read bearing in mind the perspective of a visitor from a damp, cloudy island, nonetheless the Los Angeles area is a type of desert region—just not the camels-and-sand-dunes type.

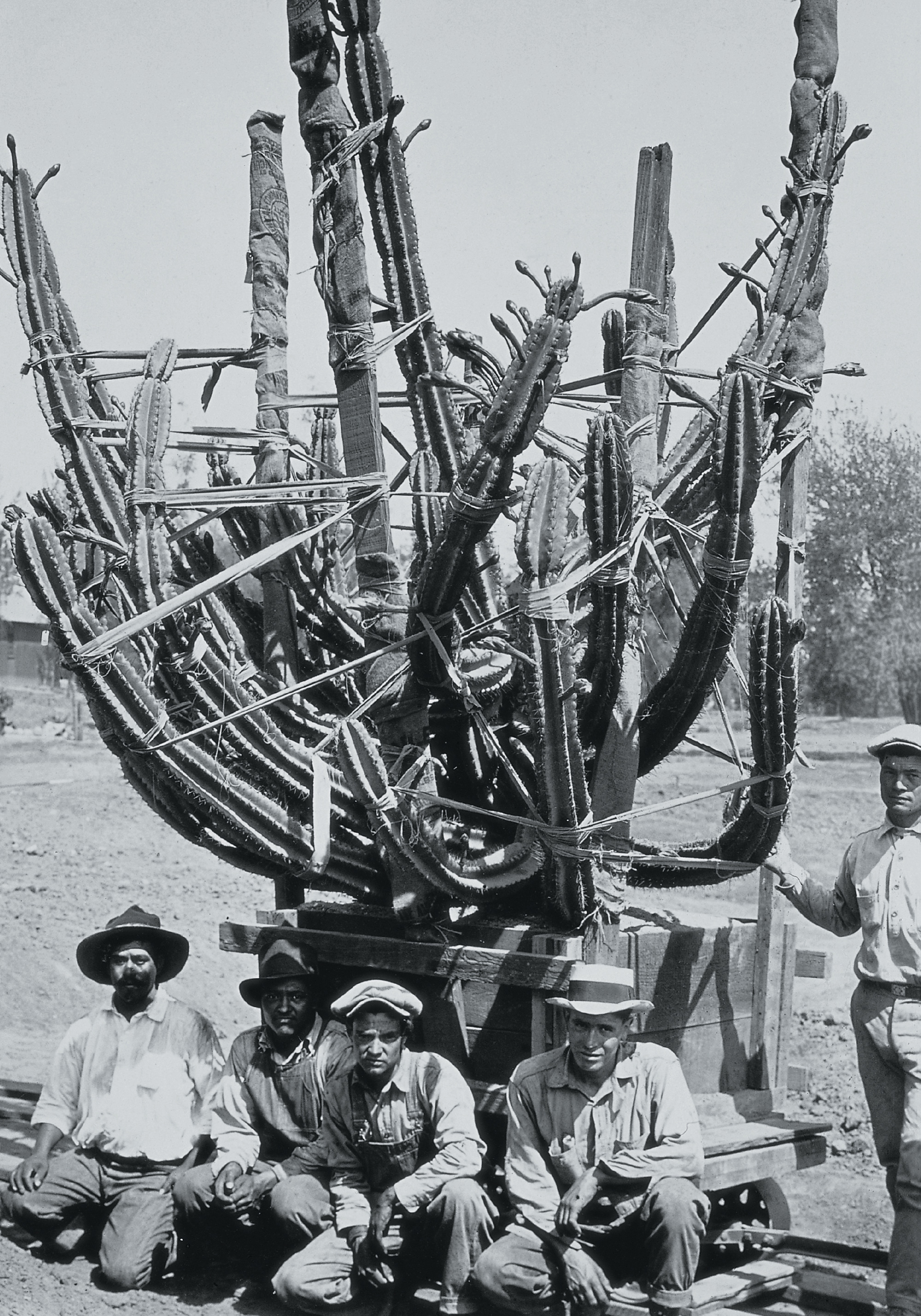

Had Johnson wandered into the lower reaches of the Huntington gardens in 1913, he might have found a plant collection more in keeping with his interpretation of the area’s climate. Begun even before the new Huntington mansion was completed, the Desert Garden comprised a collection of cacti and other “succulents” from around the world, and suggests some of the paradoxes at play in these horticultural explorations of regional identity. While part of the identity project at work in turn-of-the-century L.A. involved using irrigation to make the arid landscape bloom like an English garden, the image of the desert also held its own appeal. Many photographs of the period showed large cactus plants and other desert standards such as agaves and yuccas surrounding the homes of the city’s residents. William Hertrich’s decision to collect cacti from around the world was thus a garden project that both acknowledged the region’s desert aspects while insisting on the “foreign-ness” of a species of plant native to the area. Of the many varieties of cacti and other desert plants displayed in the Desert Garden on Huntington’s estate, some were rare but all were decidedly exotic in the eyes of Southern California’s numerous settlers from the East and Midwest states. The collecting and display by the settlers of such obvious exotics—many of them bizarre shapes, covered in spines, and sprouting truly extraordinary flowers in springtime—affirmed to the transplanted but less exotic owners that they really had escaped the more drab environs of their origins and alighted in a place unlike any other they knew.

The presence of Mexican and Mexican-American garden laborers complicates the role that gardens played in constructing a regional identity. California’s past as an outpost of the Spanish empire, and subsequently a region of Mexico, raises questions as to who and what was “native” and “foreign” to Los Angeles. The photographic and textual record of L.A. garden labor at the turn of the century includes depictions of Mexican laborers transplanting and maintaining plant material imported at great expense from Mexico and the southwest United States. The plant material designated “foreign” but exotic and therefore valued, took pride of place in gardens across the Southland. The laborers, with similar geographic origins in their recent or distant past, were designated “foreign” insofar as they were non-white, and usually occupied the lowest rungs of the pay scale. Similar ironies of transplantation affected local Japanese residents, many of whom were involved in small-scale farming, the nursery business, or other horticultural work. While plants and garden styles from Japan were very popular in L.A. at the time, immigrants from Japan were seen as a threat both to white racial hegemony and to white labor. On Henry Huntington’s estate, the Japanese garden constructed for him by his German immigrant landscape gardener—William Hertrich—has been since its completion (around 1915) one of the most popular attractions for estate visitors. For a short while, Hertrich hired a Japanese man to live in the garden, in a converted tea house bought from a failed Japanese tea garden in Pasadena.

Exotic plant material represented a type of warm-climate foreignness that Midwesterners and East Coast city exiles could collect, control, and consume. Their attitude to exotic plants contrasted with what some of them saw as the “undesirable” exoticism of immigrants in their home states. Those culturally threatened turn-of-the-century American WASPs saw Southern California, and L.A. in particular, as a new Anglo-Saxon homeland, unsullied by the immigrant “hordes” reshaping New York and Chicago. The connections in this horticultural history between plants and people are occasionally contradictory, always provocative. The local human population of Mexican origin, labeled “foreign” and “Mexican,” seem to have been regarded as generally harmless exotics. But, if resistant to the newly “native” Anglo transplants, they could easily be weeded out.

During the spring of a year spent in L.A., I became enamored of a particular section of the 134 Freeway, a route I took across the city almost daily. There were two hillsides I passed as I drove home, where the freeway curved southwest away from Glendale. As I looked out of the window, I could see the creamy white blooms of the yucca whipplei shooting straight up, sometimes 10 or 12 feet high. An expression of botanical jouissance, it was the unplanned, uncontrolled response of the un-landscaped “native.” Those freeway drives, from the lawns of L.A.’s sprinkler classes past the unkempt chaparral of the hillsides, provided me at least with a beginning and an end to this narrative of L.A.’s landscaping, the outlines of a horticultural history.

- All quotations from William Hertrich are taken from his correspondence, located in the William Hertrich Collection at the Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. The author wishes to thank the staff, librarians, and curators in the Readers’ Services, Rare Books, Manuscript, and Photographic divisions at the Huntington Library for their generous help with the research on which this article is based, and for kind permission to reproduce images from the Library’s photographic collections.

- A. T. Johnson quoted in David Streatfield, California Gardens: Creating a New Eden (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994), p. 63.

Angela Blake teaches American history at the University of Toronto and is writing a cultural history of gardens in Los Angeles.