From Carnival to Carnival™

The history and future of a Trinidadian tradition

Philip Scher

Carnival is generally experienced as a chaotic, confused, and disorienting time. All the comforts of time and place tend to evaporate in a gross assault on the senses. Reason flies away. This goes as much for the attempt at reconstructing Carnival’s history as for the actual festival itself. One of the reasons for this is that Carnival is actually not simply one event celebrated in many places. Everywhere that Carnivals have taken root and grown they have become unique events unto themselves. Whatever soil they germinate from tends to influence their final colors. In the United States, the term Carnival is often applied to a variety of fairs or temporary amusement parks that have little or nothing to do with Carnival or Mardi Gras as it is known in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. The latter are examples of New World versions of an old world festival whose origins can be traced to Europe in about the 10th century A.D. One of the most celebrated of these Carnivals, if not the largest, is in the twin island nation of Trinidad and Tobago. Lying just a few miles from the coast of Venezuela, Trinidad is the last island in the Caribbean archipelago. It was here in the mid-18th century that French planters brought their pre-Lenten revelry, and here that Africans transported as slaves and Asian Indians hired as indentured servants turned the amusements of the powerful into the ecstasies of the liberated. Yet this idea of Carnival as a celebration of emancipation itself has a long history.

From the end of the 900s to the middle of the 1100s, some reference is made in Latin documents to carnelevare, a word meaning literally “to lift up the flesh,” or “remove the meat.” The term is used in these documents generally to refer to a regularly occurring festive time during which people were meant to settle debts. It is not certain whether or not this event represented a festive moment before Lent, or the start of Lent itself but it certainly took place during the Lenten season, a time when people abstained from eating meat. Only later, in 1140 does a document appear that mentions the slaughter of animals and a parade through Rome in anticipation of Lent. Lent in the Christian calendar lasts 40 days and culminates in Easter Sunday. It represents the 40 days that Jesus retreated into the wilderness to meditate and fast, and is preceded by Ash Wednesday, at which time ashes taken from the burned palm fronds of the previous year’s Palm Sunday are applied to the forehead of the believer in the shape of a cross. Carnival was gradually incorporated into the Christian calendar as a final festive moment at which meat could be consumed and frivolity exercised in anticipation of the seriousness of the Lenten season.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, writers began to associate the rites of Carnival with ancient Roman and Greek antecedents such as the Saturnalia, Bacchanalia, and Lupercalia. There does not appear to be any direct connection with these festivals, however, and there is a large gap, historically speaking, between the last mention of these ancient rites and the first references to medieval Carnival. What appears to be the most likely scenario for the origins of medieval Carnival is that it served as a sort of ritual magnet for surviving pagan activities. That is, the ritual of a celebration before Lent attracted to it many non-Christian practices and rituals that had been enacted at approximately the same time as Carnival. These included a host of fertility rites, agricultural and hunting rituals, and forms of sun, river, or mountain worship. Many of these rituals were undoubtedly quite ancient themselves, but had clearly gone through enormous changes through the ages before they became incorporated as features of Carnival.

Carnival from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century developed into one of the most important celebrations in Europe; so much so that by the 17th and 18th centuries the Church attempted to radically reform what was perceived to be an unmitigated adventure in sin and the pursuit of pleasure. But by the early nineteenth century, however, Carnival had made a comeback in the urban centers of Western Europe, especially Paris. The popularity and fame of the Parisian Carnival spread not only to other locales on the continent, but to the growing and increasingly wealthy colonies in the New World. In the 1770s the French colonies of Saint Domingue (now Haiti), Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Saint Lucia were on the rise, rapidly becoming sources of enormous wealth for France. This wealth, generated by slave labor on sugar plantations, lead to a colonial, high society with plenty of disposable income and few of the pleasures of the Parisian metropole. Carnival emerged as an important pastime for the wealthy plantocracy who invested great sums in holding Carnival balls and masquerades. Participation by slaves was minimal, but certainly they would have been present not only as servants but also often as musicians or performers.

By 1783 the French and English had become dominant forces in the Caribbean and, of course, in North America as well. As their empires expanded, the Spanish empire diminished in the Caribbean archipelago. The small Spanish colony of Trinidad, occupied in 1498 by Columbus and almost immediately abandoned for 300 years, was, by the late eighteenth century, something of a liability for the Spanish. It was a territory few Spanish wanted to emigrate to, yet it held strategic importance for the Empire. Nearly deserted, it was an easy target for conquest by the Protestant English. In order to prevent the colony from falling into their hands, the Spanish crown issued a cedula de poblacion in 1783, a law allowing foreign settlement on the island by members of friendly Catholic nations. All immigrants would swear allegiance to Spain and would follow the laws of that country. Increasing political uncertainty in France and in the existing French West Indian colonies made moving to Trinidad extremely attractive. Immigrant planters under the cedula would receive nearly 30 acres for themselves, plus half that again for each slave they brought with them. Free “colored” planters received about 16 acres each plus 8 for every slave they brought. These new French immigrants streamed into Trinidad, bringing their Carnival celebrations with them. Yet even with this new French presence on the island, in 1797 the British seized the island for the British Empire.

The influx of thousands of new people in a very short time transformed Trinidadian society. Port-of-Spain, the benighted and neglected capital city, was gradually developed while the countryside saw the rise of new plantations and plantation houses. Along with this transposition of the French plantocracy came that society’s entertainments and diversions. Chief among these was Carnival. The early days of Carnival in Trinidad are marked primarily by lavish masquerade balls held at the homes of the island’s wealthy citizens. There is some evidence that slaves played some part in both these and their own celebrations, but documentation is slim. In the diary of a young German visitor to the island in 1832 (two years before emancipation) we read that on Carnival Tuesday, the 6th of March, “ I went to see the masks. Nearly all were coloured folk and a crowd of acquaintances, and our Negroes had organized a funeral procession to mark the end of the Carnival.” In the parlance of the day, this most likely meant that the masqueraders were free people of color who were masking, while the black slaves held the mock funeral.

The festivities of the whites, however, could be quite lavish. In the late 1830s the wife of a Venezuelan dignitary visiting the island caused quite a stir at one event by arriving in a gauze gown, sewn with hundreds of tiny pockets into which had been introduced multitudes of fireflies that blinked and glittered as she descended the grand stairway. The eyewitness who brings us this information also goes on to say with some disappointment that the grandeur of the gown disheartened the party guests so much that the evening’s festivities came to an end.

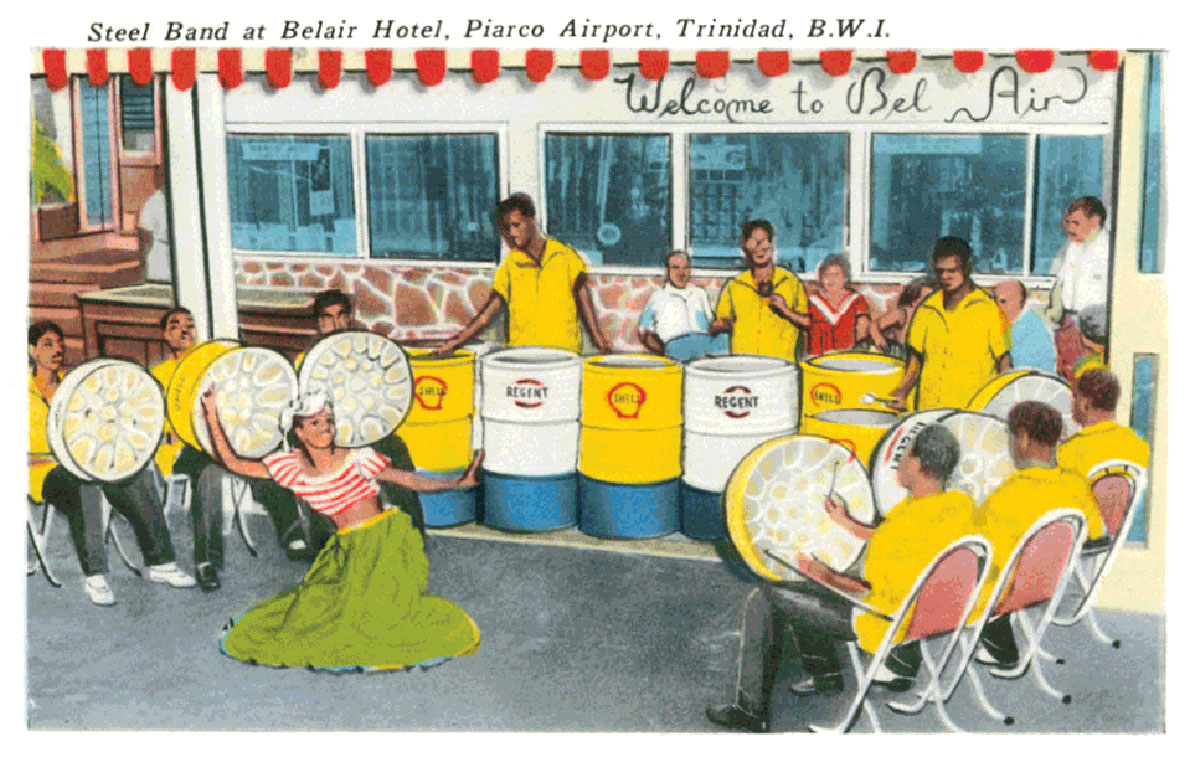

After emancipation, however, the tone of the festival changed dramatically as more and more freed African-Trinidadians began to participate. Suddenly European spectators of the festival as well as nervous Colonial officials and the local elite were scandalized by the license the revelers were taking. Pried loose from the nineteenth-century social corset, the hoi polloi claimed the avenues of the colonial city with abandon. Here is an example of the typically understated nature of elite rhetoric against this new Carnival: “In our towns, commencing with the orgies on Sunday night, we have a fearful howling of a parcel of semi-savages emerging God knows where from, exhibiting hellish scenes and the most demoniacal representations of the days of slavery: then using the mask the two following days as a mere cloak for every species of barbarism and crime.” Most of the main objections to the new Carnival targeted what was known as the Canboulay procession. The term, a Creole version of the French Cannes Brulées, or “burnt canes,” originated with the white planters. Young men from the elite classes dressed as slaves during Carnival and went out at night in a dramatic torch procession through the streets. This nocturnal parade was a sort of re-enactment of the processions of slaves who, holding torches aloft, would be sent out into the fields at night to put out cane fires during the year. The fires (many set by the slaves themselves) would have to be quickly extinguished and the cane salvaged as quickly as possible before it soured. These nighttime emergencies were periods of great excitement and must have made a distinct visual impression in the minds of the elite classes. After emancipation in 1834, however, the former slaves began staging their own Canboulay processions on August 1, Emancipation Day. About fifteen years later, however, and for unknown reasons, revelers abandoned the Emancipation Day processions and began coming out on the Sunday night/Monday morning before Carnival Tuesday. Although Canboulay itself disappeared, it was replaced by J’Ouvert (pronounced “jouvay”), a term deriving from the French Jour Ouvert, or “the day opens.” Beginning early Monday morning, J’Ouvert signals the start of the Carnival and is recognized by the ritual handing over of the keys to the city to the Merry Monarch, king of Carnival. During the J’Ouvert celebrations, masqueraders come out onto the streets dressed in rags and covered in mud, pitch, cocoa, paint, or whatever other substances can be used to messily cover the skin. This is the time of greatest license, as crowds of people move through the early morning darkness to the throb of sound systems and the rounded tones of steelbands. It is during the J’Ouvert celebrations that you see not only traditional characters, like devils and Dames Lorraine, but also what is known as Ole Mas, satirical representations of political figures or allegorical dramatizations of contemporary events.

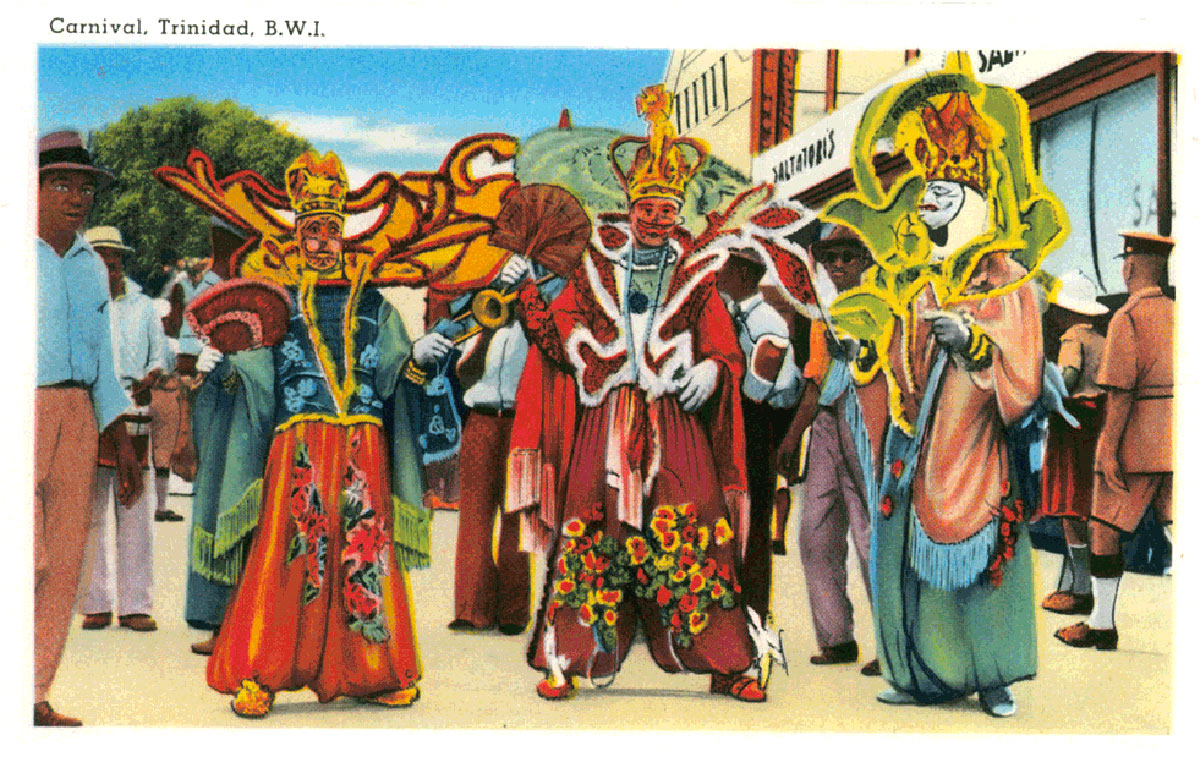

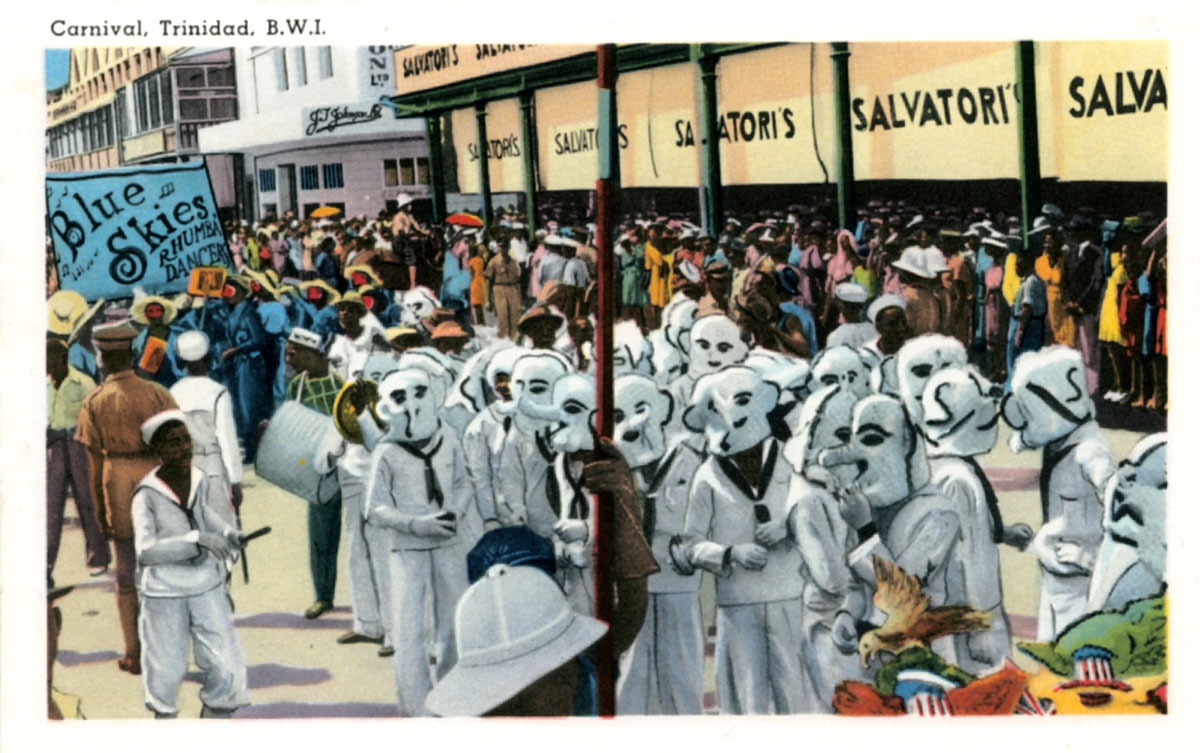

The “demoniacal representations” mentioned by the writer cited above were probably antecedents of the wide variety of Carnival characters and masqueraders that evolved during the 19th and 20th centuries. These characters developed slowly, often beginning as satirical reflections on people or issues in society, as creatures from folklore or history, or as creative elaborations of French and other European Carnival figures. Other characters, like the Neg Jadin, or “garden slave,” were originally played by aristocrats pretending to be their own servants during Carnival. These portrayals were later taken on by emancipated Africans themselves in the role-reversal performance tradition, like minstrelsy, so common in slave societies of the new world where the oppressed imitate the oppressors’ impression of them. Along with the Neg Jadin, there were the Dames Lorraine, the Burrokeets, the Clowns, Bats, Bears, Red and Blue Devils, Jab Jabs, Jabs Molassi, the Wild Indian bands, the Moko Jumbies (stilt walkers), the Midnight Robbers, the Pierrots, and later the multitudes of sailors and soldiers commandeering the streets and sidewalks from would-be onlookers. Many of these characters were formed by appropriating colonial masquerade forms and re-inventing them along African-Trinidadian or Indo-Trinidadian lines. The Neg Jadin, for instance, is an appropriation of the masters’ imitation of the field hand. Others were performance traditions remembered from African festivals; an example is the moko jumbie, a stilt-walking character whose height allowed him to collect money from spectators leaning over balconies along Frederick Street in Port-of-Spain. Each character had a unique costume and attendant performance style. Often certain characters came out at different times of the Carnival. Some emerged during the early morning hours of J’Ouvert, while others were better suited to the daylight hours. Many costume traditions had ritualized speeches associated with them, like the Midnight Robbers who held you up at mock gun- or sword-point and regaled you with terrible tales of their terrible deeds:

For the day my mother give birth to me, the sun refuse to shine, and the wind ceased blowing. Many mothers gave birth that day, but to deformed children. Plagues and pestilence pestered the cities. At the age of two I drowned my grandmother in a spoonful of water. For at the age of five, I this dreaded monarch, was sent to school but anything too mathematic was a puzzle to my brains, but when it come to snatching children’s faces, ringing their ears, biting off a piece of their nose, I was always on top! Now be quick and deliver the hidden treasure. For I am prepared to follow you to the end of the world, as the tiger follows his prey, and pierce my dagger into your heart. Your hair will make my garments. Your eyes I will take to shine as light in my lavatory, your nostrils I will make my trumpet, your brain I will make my supper...

After this tirade you were meant to hand over a penny or two. One of the masquerading traditions that horrified the upper classes the most was the pissenlit. Literally the “bed-wetter,” this piece of performance entailed a grown man sporting bed sheets or linens stained red in imitation of bloody menstrual rags. The Baby Doll masquerade involved the cooperation of two performers: a man in drag holding the “bastard baby” (a doll) of some poor bystander and making a big scene and a “policeman,” called in to force the poor victim to pay child support.

By the late 1930s and right through the 1950s and early 1960s, the sailor bands emerged as the most popular form of masquerade for the average (male) Trinidadian. Trinidadians had been imitating sailors since at least the nineteenth century when the British sailors began making regular calls at Port-of-Spain. But in the 1940s and 1950s, when Americans were stationed on Trinidad during the WWII, the sailor costume achieved the height of its popularity. Thousands of people wearing the basic white sailor outfit, some carrying talcum powder to spray on cringing spectators, would parade behind their favorite steelbands as they moved across the city. Steelbands were deeply rooted in their neighborhoods and their followers were fiercely loyal to the music, the costume, and the home turf. When two steelbands from rival neighborhoods met, pitched street battles, known as steelband clashes, were not uncommon. Some of them have permanently entered into the lore of the Carnival, memorialized in song and, at least in the case of one local folk artist, in sculpture. The steelbands, with glorious names like Desperadoes, Renegades, Red Army, and Invaders (taken from American movies), advanced on the downtown in snaking columns of warriors holding banners that read “To Hell and Back” or “D-Day.”

Many of these costume traditions, especially the more violent or morally questionable, were roundly decried during the colonial period by the middle and upper classes of mostly white and “colored” or mixed elites. Campaigns to either shut down the Carnival completely (white strategy) or reform and modify it (colored strategy) were pursued throughout the end of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. In fact, in one form or another, there are still efforts to modify, curtail, clean up, or otherwise circumscribe the license shown at Carnival time. Some of these strategies have included the outright banning of masks and drumming in the 1880s, elimination of certain portrayals or practices such as the pissenlit or the habit of sailors carrying inflated pig’s bladders with which to strike unsuspecting bystanders, or the more moderate tactic of organizing competitions and contests through which to control costume portrayals and offer prizes and other incentives. This latter strategy has been the most successful and the one most prevalent in the contemporary Carnival. Today in Trinidad, there is a competition or non-competitive exhibition for almost every aspect of Carnival. After Trinidad gained independence from Britain in 1962, Carnival and its traditions occupied a central place in the national culture of the new country. The centrality of Carnival made it imperative that the festival be something the new state and its administrators could both be proud of and begin to exploit. Tourism, not a major part of the early government of independent Trinidad’s overall economic vision, has slowly gained momentum as a potentially lucrative alternative to the oil and agricultural base of the country’s economy. Because of this there had been increasing worry in the government and related organizations, such as the National Carnival Commission, that Carnival be protected and preserved against undue influence by “outside” cultures like the United States or Jamaica (especially the influence of reggae on calypso) or appropriation by other Caribbean islands seeking to cash in on the fame of the Trinidadian parent festival by holding their own Carnivals. The primary reason for their worry is that a changing Carnival is likely to look less and less uniquely “Trinidadian,” a quality that is vital to selling the festival (otherwise, why not just go to Jamaica or Barbados). As a result of this fear of loss, the National Carnival Commission and the Ministry of Culture have explored the idea of copyrighting some of the Carnival’s most distinctive features and characters.

From the Colonial enterprise of banning the festival altogether and ridding the island of objectionable masquerades, the history of Carnival in Trinidad has come now to a sort of neo-Colonial strategy of organizing and controlling the expressive forms of its people in order to create a Carnival product suitable for both internal and external consumption. The imperatives of a world market of tourist destinations have required some government officials to become marketing experts, and local culture is the brand they must sell. But branding culture leads to a conception of culture as a collection of “things” that immediately and self-evidently represent the character of a particular people. The consumption of this culture, either by curious outsiders or by proud natives, approximates a cultural experience. Of course, consuming a cultural product is a kind of cultural experience, but one that is somewhat different than the idea of having an “authentic” encounter with a culture, which is what culture marketers are aiming for. By bringing in experts from UNESCO and the World Intellectual Property Organization, as the government of Trinidad did in recent years, the state is clearly searching for concrete ways to legally objectify expressive culture in the service of a tourist economy that requires the presence of authenticity as part of the total experience. There are multiple ironies, of course, in this, including the about-face of the middle and upper classes, which, in the past, often sought to eliminate the very cultural forms they are now desperately trying to preserve. Another problem is that the historical processes that went into the creation of these old characters (the presence of American sailors and American movies, for instance) are the same kinds of global influences that are now creating new elements in the Carnival (reggae-calypso mixing, for example), but which the government feels the need to stop in the interest of presenting Trinidad Carnival as a sort of living museum. The principal irony here is almost amusingly complex: The characters that now command the most attention from middle-class culture preservers are the ones that evolved through the nineteenth century in response to historical developments that were relevant to the working classes. Many of these same characters and masquerades were the ones the middle classes initially sought to ban. Nowadays, with great zeal, the rightful heirs to that middle-class heritage actively seek to stop the disappearance of the characters they initially condemned, while repressing emerging Carnival forms. All in all, there seems to be a grave misunderstanding of the Carnival process on the part of those in charge of controlling the event. Namely, that it is through change and reinvention that Carnival survives, but that it is that very flux that renders it impossible to grip onto, preserve, and catalogue for neat consumption.

So what do you see when you go to Trinidad these days for Carnival? Do you see a tired, mobile archaeology exhibit of exhumed characters? Do you see a vibrant, inventive group of people constantly conjuring and discarding Carnival masquerades, musical styles, and performances in favor of ever newer ones? Do you see grand costumes that took months of work to create or disposable costumes mass-produced by a vigorous Carnival industry? The answer is yes to all of these things. The Carnival has been and continues to be a staging ground for all of the most vital and current debates within the society. If in the past these debates revolved around, for instance, the presence of American soldiers on Trinidadian soil, or the falling price of petroleum, or the tension between Afro- and Indo- Trinidadians, then now at least one of these debates is about the future of Carnival itself and the shape it will take in the coming years. But controversy seems built into Carnival at some level, as if, forced to settle on something authentic about Carnival, the only thing you would be left with would be a debate about it. As the old-time sailors used to say, “if you ’fraid of powder, don’ play sailor.”

Philip Scher teaches in the Anthropology Department at the George Washington University. His book, Caribbean Carnival and the Formation of a Transnation, will be published by the University of Florida Press in 2003.