Notes toward a History of Skywriting

A language of the air

D. Graham Burnett

On 28 November 1922, shortly after noon, office workers in downtown Manhattan lifted their eyes to a startling apparition: four large, numinous letters traced in grey smoke against the blue autumn sky—H-e-l-l.

As the New York Tribune put it in a short article the next day: “There were no casualties, but even blasé lower Broadway was thrilled.” It took some time before the “stampeding stenographers discovered that the message was not of supernatural origin,” and only then did they go “calmly back to their business of eating lunch among the ancient tombstones and time-worn inscriptions of Trinity churchyard.”[1]

A fifth letter—an o—had changed the mood.

This (ambiguous) inscription has traditionally been taken to mark the origin of skywriting in the United States.

• • •

Across the Atlantic just a few months earlier, on 31 May, a sizeable audience gathered to watch the Derby Stakes at Epsom (lorgnettes at the ready) found their attention redirected high over the infield to a nearly invisible World War I biplane, which began tracing a legible cursive inscription in the clouds. At the stick of the small se5a fighter sat Captain C. Cyril Turner of the R A F—the same pilot who would later interrupt lunching New Yorkers with that brimstone shiver. As chatter filled the stands below, a smoky scrawl spelled out Daily Mail above the racetrack.

Reporting breathlessly the next morning on their own advertising coup de théâtre, the Daily Mail declared a new epoch in human communication:

This remarkable achievement, to be repeated, weather permitting, this evening over busy London streets, tells us in words as plain as can be that a new era has opened in signalling from the air, marking an advance which is bound to produce far-reaching results, particularly as regards warfare both on land and at sea. We can now write orders to armies and navies on the sky as plainly as a schoolboy writes on his slate. An aeroplane can disappear in a cloud of its own making, or conceal the ships it is escorting in a dense mist. Other wonders doubtless are wrapped up in “sky-writing.”[2]

Some schoolchildren who saw the inscription out the window of their classroom asked if an angel was writing in the clouds.[3]

The Daily Mail incident may have been the first instance of skywriting in the United Kingdom—though ambiguity persists. There is good evidence that a previous and less glamorous effort by the same team (Major J. C. Savage, who had patented the avionic smoke-generating mechanism the previous year; his pilot, Turner, who had been practicing the necessary maneuvers for months) was more or less effaced by the publicity around the Derby Stakes caper. A passing mention in a short article in Flight, the newsletter of the Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom, notes without fanfare that earlier in the same week, Savage and Turner had written Castrol in the sky—and there seems little reason to doubt that they did indeed make a flight touting this engine lubricant (then used in both airplanes and automobiles).[4] Castrol, then, was probably the first word in the English skies, but the company did not possess a newspaper with which to immortalize their own innovative self-promotion.

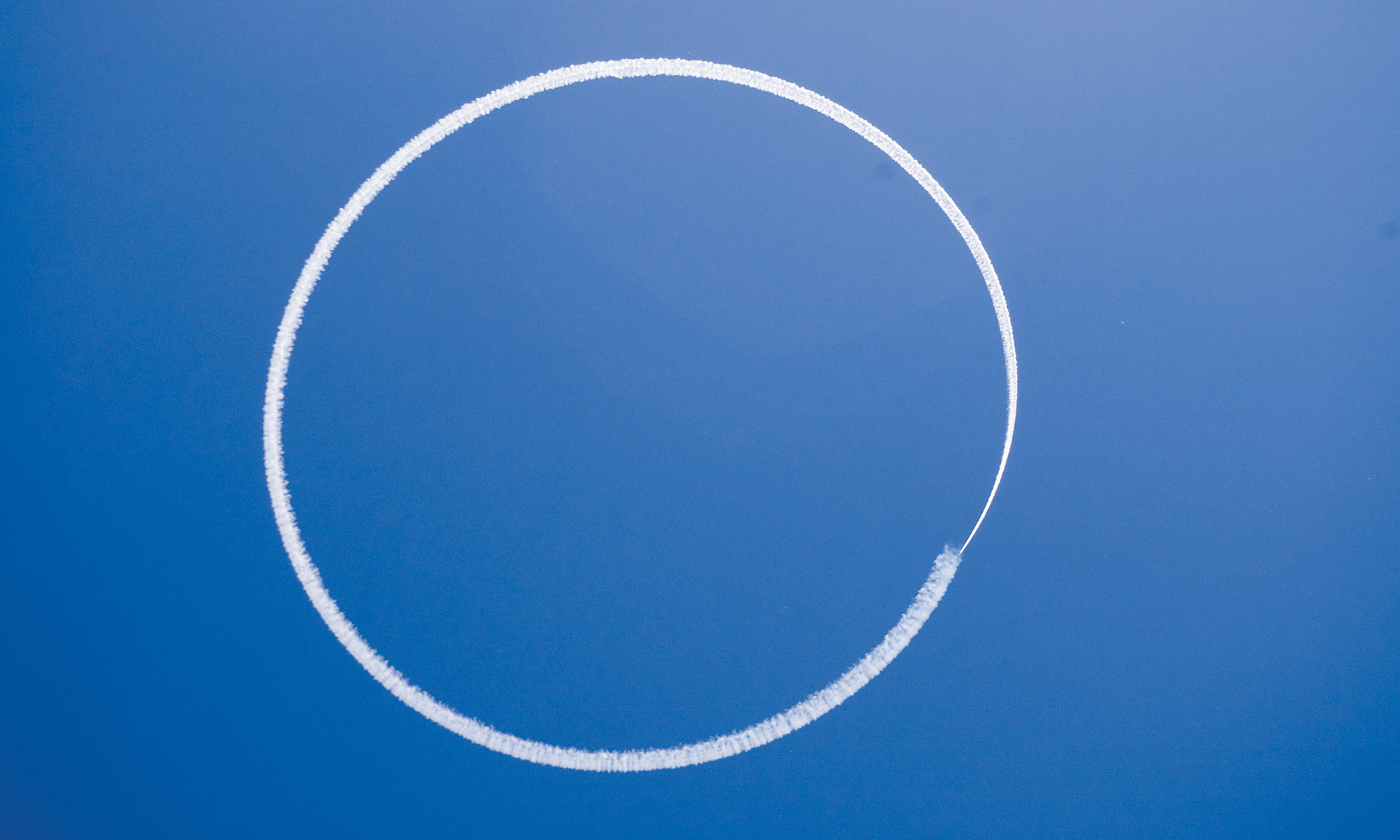

Having been careful to secure his intellectual property, Major Savage was prompt and relentless in his campaign to commercialize the technology he had developed. At the heart of the mechanism lay a relatively simple apparatus that permitted the pilot, by means of a lever in the cockpit, to release a small stream of fluid (different materials were used, and treated as trade secrets, but any ordinary lightweight, low-viscosity oil, such as Castrol, will work) onto the hot metal of the aft-canopy exhaust manifold. Billows of thick trailing smoke resulted. The work of actually making text from this stream lay with the pilot, who needed to trace a penmanship course in the sky (working out of the sun; reversing the letters so they would read correctly from below; and being careful, when revisiting an extant component of a letter, e.g. crossing a t, to do so several hundred feet above or below the altitude of the existing element, so as not to blow it away—the dimensional separation remaining invisible to earthbound readers).[5]

Patent disputes and litigation aside, Savage and the companies he spawned succeeded in making skywritten commercial advertisements a nearly ubiquitous feature of urban skyscapes on both sides of the Atlantic in the interwar period—so much so that legislation was several times proposed (and Parliamentary hearings actually conducted) to address what was thought by some to be the unacceptably unregulated and fundamentally unaesthetic clouding of the heavens by advertisements for insurance, cigarettes, soda, and patent medicines.[6] One paper in the early 1920s ran an opinion piece on the topic under the title “Page John Ruskin!” asking what the deceased English aesthete would have made of the “solemn dome of heaven” serving “to herald particular makes of shoes, hams, catsups, stove polish and underwear.”[7]

In this context, the early history of skywriting must be treated as a significant (if mostly overlooked) aspect of the larger transformations in advertising culture that attended the consumerist bubble of the 1920s and the rise of the automobile—a conjunction best exemplified in the increasing ubiquity of the new “billboards” in the peri-urban landscape.[8] Indeed, as early as 1925, the history of skywriting itself could be résuméd by one commentator under the simple title “Bill Boards of the Air.”[9]

Shortly after writing Hello in the sky over Manhattan, Turner smoke-wrote the telephone number at the Vanderbilt Hotel where he and Major Savage could be reached. They were trying to scare up business. In this sense, the first heralded skywriting in the United States was meta-advertisement: an ad for ads.

• • •

So much for what we might call the “received” history of skywriting, which has long heralded Messrs. Savage and Turner’s 1922 debut, while emphasizing the close links between the emergent art of avionic air-inscriptions and the interwar apotheosis of the ad men, who were anyway ascendant in the period.[10] Is a different account of writing in the air possible? It is. And in what follows I will work to sift out an earlier and more uncanny genealogy for this ethereal feature of aeronautical modernity: what we might call the ghost-semiosis of human flight.

For starters then, en route to a revisionist treatment of skywriting, we would do well to reach back and take another moment with those schoolchildren musing on the angels—or indeed, with those stenographers who paused at their sandwiches beneath the vaporous name of Dis (and cast an anxious glance, we may suppose, at the headstones of Trinity graveyard).

Both these scenes, properly regarded, help evoke something of the ecstatic-transcendent strangeness of the actual emergence of smoke-words in the sky—a strangeness too easily overlooked by an overhasty assimilation of early skywriting to mere avionic wheatpasting. One early newspaper, reaching for analogies (and perhaps expressing a sublated premonition of the general death dance of the giddy 1920s), went so far as to liken the new technology to the writing on the wall at Belshazzar’s feast.[11]

I propose that we linger with that image—monitory, disruptive, inscrutable, ultimately maddening—as we work to recover forgotten elements of a fleeting moment: the tender interlude before wispy, mile-long texts in the heavens came to be routinized as yet another shill.

A few suggestive fragments along these lines can indeed be culled from the archive. For instance, the satirical journal Punch opened a cynico-comic window onto the weirdness of it all, running a skywriting cartoon in 1922 that depicted an English farmwife running to her husband crying, “Coom, Jarge, quick! One o’ them woireless messages ‘as caught foire.”[12] It is a joke that plays on the proliferation of new and unsettling technologies of communication in the period, even as it affectingly invokes a kind of generalized atmospheric volatility that proved prophetic in the context of a Europe suspended in the brief truce separating two world wars. The joke was presumably funnier to those who did not yet know the German word flak, which would soon come into English usage. Radio operators calling down flaming skies were indeed in the offing.

The unstable and the imminent also glints when one comes upon evidence of a “path not taken” in the development of the new skywriting technology. The most touching of these? Perhaps a few visionary allusions to the way that fleets of planes, equipped with colored smoke-generators, might soon be able to produce gigantic and ethereal “paintings” in the heavens.[13] The proposition secretes something of the deranging glory of the visionary Italian Futurist Fedele Azari, who in his 1918 manifesto “Il Teatro Aereo Futurista” called for vast sky ballets of mechanized warbirds wing-dancing in the name of the avant-garde. Azari killed himself in 1930, by which time there were lots of ads in the sky for Pepsi-Cola, but no celestial polychrome smoke paintings to be seen. Nor did Morse code skywriting get picked up as a form of visual telegraphy (as some predicted)—though the mooted possibility reached back to traditions of Amerindian smoke-signaling, and promised one of those folds in time that can provide reassurance in times of radical change and discontinuity.

A nervous allusion to the possibility that the technology might be converted for use in spreading poison gas proved more prescient.[14] Major Savage himself would later work on versions of his machine that could be used to mist fields with insecticide—yet another instance of that jittery exchange between killing animals and killing people.

And it is here that we reach something like a properly revisionist “proposition” in relation to the received history of skywriting, a proposition that might be summarized as follows: excessive emphasis on the dominance of the advertising business in the history of skywriting obscures the deep complicity of early skywriting and military avionics.

The martial matrix of the whole activity in the 1920s and 1930s is hidden in plain view.[15] Not only were Savage and Turner both former raf pilots with wartime experience over continental Europe, there is good evidence that Savage’s early experimentation with smoke generation from flying planes proceeded from interest in signaling systems for military use.[16] The Daily Mail’s original story on skywriting emphasized not only that possibility but the still more dramatic notion that airplane-generated smoke screens could become nimble and protean forms of battlefield camouflage. And while this did not take shape, streams of smoke were indeed used to advance military designs in other ways, including aerodynamic testing—one of the applications touted by Savage and his promoters.[17]

But none of this goes to the heart of the matter. What is essential to recognize is that the tight and intricate aeronautic maneuvers required to produce legible script in the heavens were exactly those required for air-to-air combat. The vrille, the renversement, the virage, the retournement, and the notorious Immellmann turn—indeed, the entire repertoire of the tactical airman working to gain position on an opponent—all of these became the essential penmanship of smoke calligraphy. Which is to say, in early skywriting there exists a perfect and reciprocating scintillation between writing and fighting. Skywriting must be understood as nothing less than the grammatology of the dogfight.

All of this was perfectly clear to contemporaries. In fact, one of the primary arguments brought by defenders of skywriting against those who sought to regulate or even ban the practice (in the name of general aesthetic well-being, or out of a narrower concern for the creep of commercial exhortation into every sunset and seascape) was precisely that skywriting provided a totally unique way to maintain, in peacetime, a well-lubricated and highly skilled cohort of aces.[18]

Fair enough. But we can go much farther than this in our historical reappraisal of the skywritten. For, in fact, recently surfaced sources clearly demonstrate that Savage and Turner were very much not the first practitioners of the art in question, which antedated 1922 by a considerable margin. An excavation of these largely unexamined materials points to something closer to a proper counter-history of writing in the sky: a genealogy for this practice that locates its origin not in the precision maneuvers of the aerial killers, or the petty solicitations of lumpen shopkeepers, or indeed at their unholy convergence, but rather in the cryptic traces of what we might call the Icarian carnivalesque. What these earlier sources suggest is that the first words in the sky were not vaporous product placements, but in fact smoldering, calligraphic ululations howled at the moon. Billboards in the air? On the contrary. An indecipherable babble of mist and flame, more like an Ursprache of high-flying linguistic délire.

For it turns out that skywriting was not born of underemployed raf pilots trying to sell soap (grooving their maneuvers for hours at the airfield to teach their rudder-tongues to articulate legible smoke-speech), but rather began in the corybantic “aerial insanity” of a man who came to be known as the Human Comet.

• • •

The diminutive Art Smith, who stood a little under five feet three inches, was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1893. At the age of seventeen (just a few years after the Wright brothers’ first successful flight), Smith persuaded his parents to take out a mortgage on the family home—to afford him $1,800 to build his own heavier-than-air flying machine. Lore has it that his mother sewed the canvas coverings for the stick-structure wings. The craft crashed on its maiden flight, but Smith survived, recovered the motor from the wreckage, and persevered. Within two years, he had become a Midwestern celebrity as one of the new generation of fearless birdmen—a reputation burnished to national brightness by his orchestrating, in 1912, the first “air-elopement.” He succeeded in sweeping away an eighteen-year-old (French) Indiana girl by the improbable name of Aimee Cour and winging her to Hillsdale, Michigan, for a matrimonial union ostensibly unblessed by the bride’s parents, who were reported to have had stakeouts at the relevant train stations. The drama of the occasion was immeasurably enhanced by a Romeo-and-Juliet crash landing in a cornfield just south of the nuptial destination—an accident that left both flyers unconscious. The newspapers, which printed lurid images of the wreckage, reported a ceremony in which vows of eternal fealty were exchanged by heavily bandaged lovers.[19]

The marriage would not survive, but the bravura of its inception catapulted Art Smith into the first rank of aeronautical stuntmen. In those years, said ranks were continually thinned by plunging death. And it was in fact a particularly lurid spectacle along these lines that afforded Smith his big break. He had drifted out to California by early 1915, and was effectively an understudy to the most famous American aviator of the day, Lincoln J. Beachey, the main attraction at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Beachey, the “Demon of the Skies,” was a melancholic defier of fate who had for years conducted a very public love-hate relationship with stunt flying. On the one hand, he had pioneered a host of gasp-inducing tricks—including a world altitude record, upside-down flight, the dreaded “inside loop,” and even a mock dive-bomb of the White House. On the other hand, he felt himself to be personally responsible for twenty-four young aviators who had died attempting to emulate his antics at the stick. He spoke openly with the press about himself having shaken hands with the reaper of souls—and it is not clear that he was simply providing good copy. On 14 March 1915, death called in their deal. In front of some fifty thousand people gathered along the marina, and perhaps another two hundred thousand looking on from outside the fairgrounds, Beachey failed to pull out of an extended inversion. It seems the force of his maneuver snapped the wing struts, sending the aviator and his crumpled craft on a fatal dive into San Francisco Bay.

Art Smith got the call. And as if intent upon whisking away the sepulchral taint of his colleague’s harrowingly public demise, Smith instantly became a whirling sky-dervish the likes of which no one had ever seen. He flew like a man possessed. The papers coined a new phrase, “aerial insanity,” to capture the mad terror of Smith’s frantic abandon: “Smith appeared to lose all control of his machine, rolled and tossed about in the gale that swept through the Golden Gate like a ship tossed in a storm. His biplane tumbled over and over, forward and backward; then suddenly the aviator would, with a long, graceful loop, come out of the seemingly dangerous condition and would again sail away.”[20] He looped the loop twenty-one consecutive times. He “tangoed.” He dipped sideways. He did something called a “lunatic glide.” Another paper reported it this way: “In his afternoon flight it seemed as if the boy had gone mad. His machine dipped and curved and hesitated … a kite in a gale could not act more insanely. Right over the crowd and not 500 feet high, he rolled over sideways, summersaulted forward and backward, and then rolled across the wind like a barrel going down stairs.”[21] One headline ran simply: “Crowd Holding Its Breath Expected Tragedy.”[22]

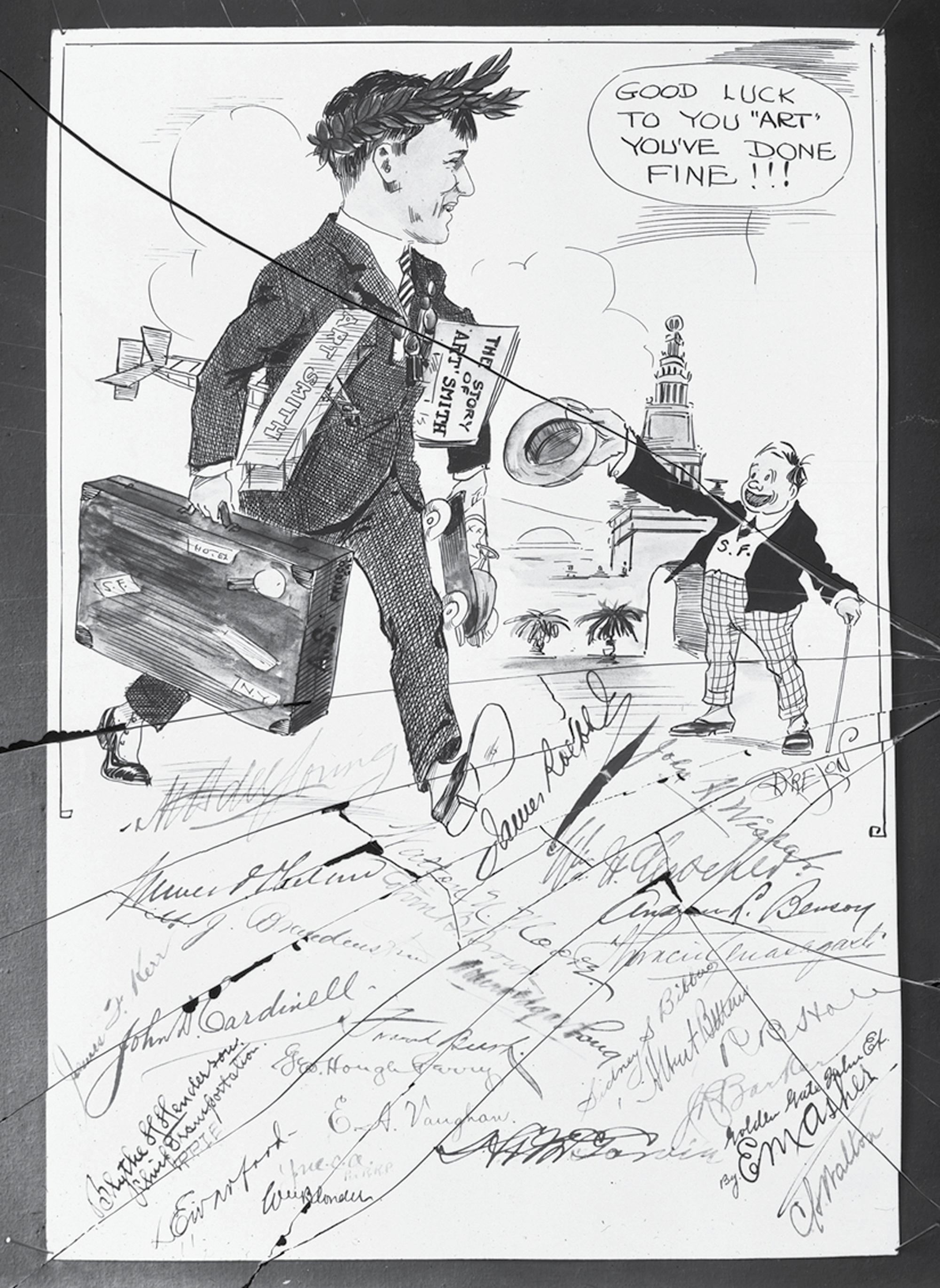

Below: His final farewell? Like the inscription made by Smith on 8 August at the end of his first stint flying for the exposition, his looping flight path on its closing night has also been interpreted as a written goodbye note. Courtesy San Francisco Public Library.

By late spring, Smith was the toast of San Francisco, and yet it would appear that he experienced an unsettling need to continue to surprise and amaze. It was in this period that he pressed forward a dubious line of stunts that earned him the sobriquets Nighthawk, Human Rocket, and eventually Human Comet—to wit, nocturnal flights in which his paper-light and inflammable contraption would be stuffed to the guy-stays with flares and fireworks and smoke-pots, which he would set off in mid-air. Smith did not invent airborne pyrotechnics, but in the summer of 1915, he took them farther than any aviator had dared: “Smith’s night flights are distinctively his own,” wrote the Evening Tribune of San Diego in July; “No rivalry exists among other aviators in this particular line. He is the only one known today who flies at night with his planes enveloped in fire.”[23]

Here we come to the unexpected hinge in the blacklit history of skywriting. Sometime in mid-June of that year, an anonymous photographer working for the Cardinell-Vincent Company (the official photographers of the Exposition) made a long-exposure shot of one of Smith’s night flights. The technique would appear to have been the same as that used for other nocturnal documentation of the well-lit pavilions of the Expo, but in the context of Smith’s suicidal rocketry, the photographer’s emulsion recorded an exquisitely fluent and expressive ribbon of brightness across the black expanse of night.[24]

It looked for all the world like a signature.

Or anyway, it would seem that Art Smith himself (along with many others) quickly came to read it as such. Indeed, that very same image would soon be reprinted under the tagline, “Night Photo of the Famous Aviator Writing His Name in the Sky.”[25]

To be sure, there is no reason to think that this is what it “represented” (to Smith or anyone else) at the moment that the demon-aviator was hurtling to earth in a ball of flame feeding greedily on the onrushing night air and the photographer depressed his shutter-stop and held it down for fifteen long seconds. On the contrary, similar images—even this one itself—had previously run under headlines like “Burning Fireworks Leave Long Trail of Brilliance as Daring Flier Completes Loop after Loop in Midair.”

But we are here on the cusp of something more than a mere “misreading”—as if the world’s first instance of sky writing were a case of mistaken identity, a misprision, a curling tendril of thanatological parapraxis. Rather, we are here in free fall from the cusp of writing itself. After all, the degree zero of writing might be understood to be the scrawled “mark” of an illiterate asked to sign the unfamiliar page. Signatures are inscriptions inked across the borderline separating signifier and signified. They are signs still possessed of the primitive magic that entangles people and things. They participate in the logic of similitudo, correspondence, ressemblance. This is not the linguistics of Saussure, but that of Paracelsus.

Flaming comet tails plummeting in mad loops, downward to darkness on extended wing? This was indeed Art Smith’s signature. He was surely writing his name in the sky. Writing his name. Signing his fate.

He would die, of course, a few years later, alone, in a fiery plane wreck on a dark, cold night.

If one squints long enough at the squiggle, it does almost look like it could be trying to say, “Art Smith.”

• • •

There’s more, of course. (There always is.) One could play it all out. But does it matter? Writing and unwriting. Words and fire. Soaring and falling. Language and nonsense. As if the project of making meaning in the heavens were a kind of exhaust, a spitting in the wind. Shortly after the “signature” incident, when the papers were full of ads for the “daring young aviator who writes his name in the sky,” Smith promised to celebrate “Press Day” at the Panama-Pacific Expo by writing the word press in the sky in a “trail of fire,” a stunt to be accompanied by a sadistic-clown burlesque on communication itself: the mid-flight hurling of a prominent San Francisco newspaperman into the bay.[26] The aviator seems to have earned his wings in allegory.

Perhaps, though, to be faithful to the task of historical revision, we should bracket all this overdetermined poignancy, and instead dutifully rehearse how Art Smith also experimented with skywriting in actual smoke in the same period, and appears to have had some modest success by the end of the summer of 1915—thereby stealing the march on the so-called invention of Savage and Turner. Immediately, however, one stumbles on evidence that his best-heralded effort to smoke write consisted in forming a short-lived valediction—the words Good-By, which the papers said could be read in the whirlings of his wake “with a little imagination.”[27] (Was it there? Or wasn’t it? Was he?)

And indeed, having read one’s way through all the materials, it is difficult not to see that notable smoke-farewell as little more than a discursive elaboration of the terrifying stunt he had pulled on 26 May of that year—perhaps his definitive signature. That afternoon, before a huge audience, high in the air, he “ignited a great powder pot” placed under the bonnet of his plane, and then, smoke billowing out of the compartment, cut his motor, drifting in the silence of a free fall as the terrified spectators watched—certain his engine had exploded in midair, and that they were watching the ephemeral sky-smudge tendril of his final, sacrificial auto-immolation.[28]

• • •

Skywriting: the by-product of a relentless and imaginative effort to document a death wish.

- “‘H-e-l-l,’ in Letters Mile High in Sky, Jars Manhattan,” The New York Tribune, 29 November 1922. Unlike most modern skywriting, these early instances of the art seem to have been exclusively in cursive.

- “Writing on the Sky,” The Daily Mail, 1 June 1922.

- “Sky Writing Pilot,” The Daily Mail, 3 June 1922.

- “The Writing in the Sky,” Flight, 8 June 1922, p. 330, and “Writing in the Sky: Something More Than an Advertising Stunt,” Flight, 17 August 1922, p. 475.

- Savage’s device permitted the flyer to turn the flow of smoke on and off, so as to “lift the pen” to make a finishing stroke.

- The Skywriting Corporation of America, founded shortly after the New York debut of Savage’s technology, was central to the development of the commercial application of skywriting in the United States. A considerable archive of related materials were recently acquired by the Smithsonian, and catalogued as the S. Sidney Pike Collection. In 1932, the House of Commons created a committee “to consider the use of appliances for projecting writing or other displays on the sky” that ultimately declined to recommend significant restrictions on smoke writing in the sky, but did recommend a total ban on the (related, but now forgotten) practice of “sky-shouting,” which involved using airplanes and loudspeakers in an aerial version of “barking” promotion. See “The Sky Writing [sic] Report,” pp. 617–618, and “Sky Writing [sic],” p. 638, both in Flight, 8 July 1932.

- The Ruskin reference can be found in The Anaconda Standard, 5 September 1922.

- On the history of billboards, consider Catherine Guidis, Buyways: Billboards, Automobiles, and the American Landscape (New York: Routledge, 2004) and John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle, Signs in America’s Auto Age: Signatures of Landscape and Place (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2004).

- Ernest Jones, “Bill Boards of the Air,” National Aeronautic Association Review, vol. 3, no. 8 (August 1925), pp. 117–118.

- It is worth noting that there is, in fact, much less scholarly history of skywriting than one might expect. My bibliographical survey in preparation for writing this essay turned up more critical commentary on the brief skywriting scene in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) than can be found in the entire historical literatures on aviation, advertising, the history of technology, cultural history, etc. But consider Scott M. Cutlip, The Unseen Power (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994).

- The Belshazzar’s feast allusion comes from “Sky Advertising in Daylight,” The Bay City Times Tribune, 22 June 1922. The specification of “daylight” in this piece points to an easily forgotten context for smoke writing from planes: projective advertisements that made use of focused (and filtered) beams from arc lamps or other bright light sources. These had existed in various forms since at least the mid-nineteenth century. For an interesting discussion, see Erkki Huhtamo, “The Sky is (not) the Limit: Envisioning the Ultimate Public Media Display,” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 329–348.

- See Punch, 14 June 1922, p. 461.

- “Words Miles Long Formed of Chemical Smoke Trailing from Airplanes,” The Dallas Morning News, 24 September 1922; the article was widely reprinted, and I remain unsure as to where it originated.

- Ibid.

- The point was recently noted by Paul K. Saint-Amour in Tense Future: Modernism, Total War, Encyclopedic Form (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 114, footnote 32.

- Savage actually took out a patent in the United Kingdom in 1919 for such a signaling system, but he claimed to have experimented with it during the war. The topic is discussed in the 1938 US federal patent dispute case Savage v. Phillips Petroleum Co.

- “It therefore appears possible that these smoke trails may prove of the greatest value. For instance, small jets of the smoke, allowed to emerge in front of a flying aeroplane and travelling back over its various parts may, if observed, or better, even, photographed and cinematographed from another machine, teach us a very great deal about such things as downwash, slipstream effect, eddies around projecting parts, and so on.” From “Writing in the Sky: Something More Than an Advertising Stunt,” Flight, 17 August 1922, p. 475.

- “If it were merely a matter of smoke advertisements against the sky, in spite of their being but temporary ‘emanations,’ there would be little to be said against the prohibition. But surely this is a case of helping to maintain that keeping-fit ‘Kruschen feeling’ [period slang for a “state of vigor”] plus very valuable smoke screen experience against future (however distant) war-time requirements. Lord Birkenhead made the very telling point that this company is maintaining a large staff of pilots, mechanics and machines, and without a farthing paid in subsidy by the nation. Surely this is an important consideration, as both the personnel and material would be available in case of national emergency.” From “Skywriting,” Flight, 24 May 1923, p. 274.

- The incident was widely reported, making the front page in some newspapers, e.g., “First Elopement by Aeroplane; It Almost Ends Disastrously,” Riverside Enterprise, 4 November 1912. Was it all a publicity stunt? It is not impossible, though I can find no concrete evidence to support the suggestion. On “aerial nuptials” in the early age of flight, see Joseph J. Corn, The Winged Gospel: America’s Romance with Aviation, 1900–1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 56.

- “Art Smith, New Exposition Aviator from Chicago [sic], Does Wonderful Stunts in the Air,” The Evening News, 6 April 1915. See also “Aerial Insanity, Latest Thriller,” The San Diego Union and Daily Bee, 6 April 1915.

- “Night Stunts of Boy Aviator Set Watchers’ Hearts Aflutter,” The San Diego Union and Daily Bee, 1 August 1915.

- Headline from The Evening News, 1 May 1915.

- “Daring Aviator to Make Flights,” Evening Tribune, 31 July 1915.

- It appears that several of these photographs were released to reporters on or about 17 June 1915. One (that was subsequently reproduced many times) ran as “Night Picture of Art Smith, the Famous Aviator, Looping Loop” in the San Jose Mercury News on 20 June 1915. Another (also many times reprinted) first appeared, as best I can discern, as “An Illuminated Aeroplane Looping the Loop over Panama Expo Grounds,” in the Arizona Republican on 18 June. It should be mentioned that a much less spectacular short exposure of an earlier flight, showing only a brief arc of its course, ran with the tagline “Smith’s Biplane Like a Flaming Comet” in the San Francisco Chronicle on 25 April 1915. Lacking the calligraphic sweep and intricacy of the images made later, it apparently did not lend itself to being read as a legible inscription. It is also worth noting that a newsreel film of Smith’s night flights appears to have circulated to movie houses in the summer of 1915; the Morning Olympian of 26 June 1915 advertised a screening of “Sensational Night Flights of Art Smith and Auto Wrecks” at the Ray Theater. For more on Smith’s night flights, see Noelle Belanger and M. Elizabeth Boone, “‘Art’ Smith, Flying at Night, and the 1915 San Francisco World’s Fair,” Panorama, vol. 1, no. 1 (Winter 2015). Available at journalpanorama.org/art-smith-flying-at-night-and-the-1915-san-francisco-worlds-fair.

- This tagline, which accompanied the image in “Birdman Cuts ‘Aerial Insanity’ Capers,” The San Diego Union and Daily Bee, 1 August 1915, seems to be the first to identify one of these long-exposure images as a legible inscription of the aviator’s name. The previous day, the same paper ran a short piece under the title “Master of Air Sought by Fair” that opened: “Some persons have a difficult time in writing their name with a pen or pencil so that it can be read, but what do you think of a daring young man, who has not yet cast his first vote, writing his name in the sky?”

- “‘Art’ Smith’s Farewell Flight on Press-Day,” The San Jose Mercury News, 11 July 1915. It isn’t clear that Smith actually performed either of these stunts.

- “‘Good-By,’ [sic] Writes Art Smith in Air,” The San Francisco Chronicle, 9 August 1915. Citing a San Francisco Examiner article from 7 May 1915, Belanger and Boone state that Smith wrote the word “Zone” in smoke in the air in early May. In fact, the Examiner reported Smith promising to do so on “Zone Day” later that month (27 May). While this promotional promise was reiterated in advance of the occasion (and may have contributed to record attendance at the fair that day), there is no contemporaneous confirmation that Smith performed the stunt. On the contrary, “Art Smith Works Out Smoke Chain,” a San Francisco Chronicle article from 2 June 1915, states that weather conditions had prevented Smith from making clear smoke figures prior to that date. This may be so. Regardless, while it appears to be true that Smith had been able to loop smoke threads in the sky as early as April of the same year (see the photo accompanying “Thousands Watch Boy Flier’s Acrobatics,” The San Francisco Examiner, 24 April 1915), I have found no evidence that Smith actually made a legible smoke inscription before 8 August of 1915. The existence of premonitory talk of words in the sky in May 1915 underscores that the idea of skywriting was very much “in the air” in mid-June, when the dramatic long-exposure photos of Smith’s illuminated trajectories were first seen as linguistic. For further documentation of Smith’s apparently writing in smoke later in the year, see “The Sky Scribbler,” The San Jose Mercury News, 9 December 1915.

- “Art Smith’s Engine in Mock Explosion,” The San Francisco Chronicle, 27 May 1915.

D. Graham Burnett is an editor of Cabinet and teaches at Princeton University. Recent collaborative work includes “The Bog˘aziçi Rolls” at SALT-Galata, Istanbul, and “The Trochilus Exercise” at the Asian Arts Theatre, Gwangju, South Korea.