The Barbers of the Villes

The container and Haitian tonsorial art

Richard Fleming

Port-au-Prince is home to an astonishing quantity and variety of barbershops and hair salons, so many that one could be forgiven for imagining that Haitians do little else but get their hair done. Just as in the so-called inner cities of the United States, grooming-oriented businesses are an abundant element of the urban fabric. Start-up costs are minimal, there is no education requirement or other significant barrier to entry, and demand is ensured through the irrepressible biology of hair growth.

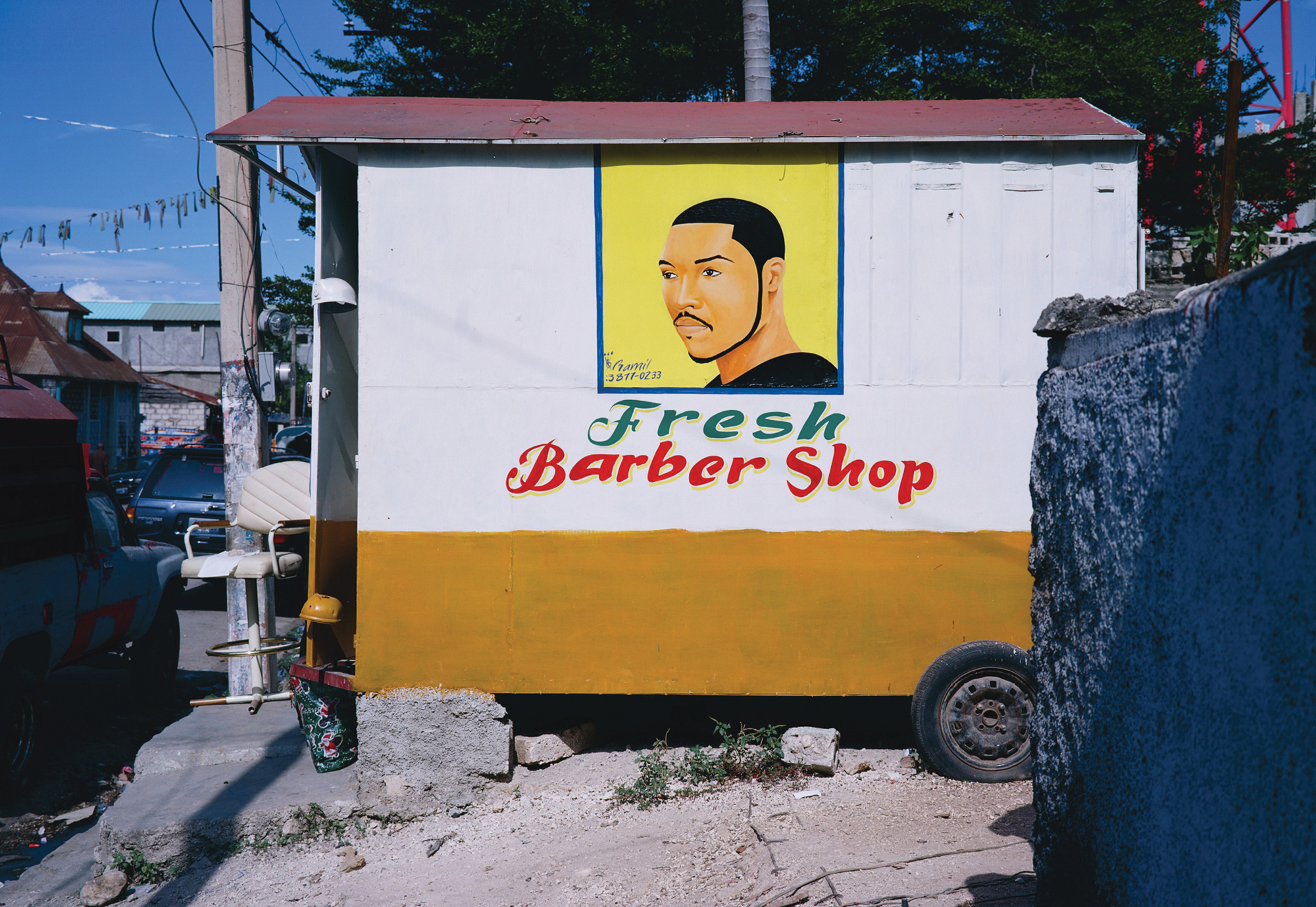

Almost all these salons are adorned with paintings, usually large portraits of international soccer stars, American rappers, or other iconic heads copied from hair-care product packaging or from the well-thumbed pages of catalogues filled with the latest hairstyles. Ranging in style from the naïf to the photorealist, such images are hand-painted directly onto the exterior metal or cinderblock walls of the enterprise. Produced by a significant and vibrant cottage industry of artists, these images are typically chosen by the barbershop proprietor, with guidance and source material offered by the painters. There is an obvious affinity with Africa, where barbershops the length of the continent advertise themselves with painted signboards, but in Haiti they are larger, and more sophisticated.

Many of these Haitian shops are housed in shipping containers. As in the United States, reliance on imports makes Haiti a dumping ground for them; the inexpensiveness and prevalence of these steel boxes is a physical manifestation of a balance-of-trade deficit. They arrive full of product, but with nothing to fill them on their return journey, their value plummets. Dented and stranded, they take on new lives as warehouses, small businesses, and even as homes. The first choice for a barbershop is not the enormous, corrugated intermodal container, but one of its smaller cousins, the back of an expired box truck, for instance. Placed on concrete plinths, lined on the inside with mirror, the doors thrown open to the Caribbean sunshine, these one-time signifiers of delivery, mobility, and commerce are transformed into permanent fixtures of the contemporary architectural vernacular. They become social clubs, places to gather and gossip and watch a communal television just as much as somewhere to get a haircut. Most have a cooler, or a refrigerator. They sell cellphone airtime, photocopies, and sometimes shoes and clothing. Anything to attract custom. As Michel Lafleur, one of the painters, told me, “If you’re going to go down and watch the football match at the barbershop, you pretty much will need to buy at least one Coke, or a beer.”