F-Hole

Selling vans, smashing guitars

Justine Kurland

I want to tell you why I sold my van. It’s not the first van I’ve left behind but it might be the last. I would like to publicly renounce a belief system that once seemed useful and true to me; I’ve outgrown the romantic escapism of this mode of travel. The boy who bought my van was excited to have it. He had just graduated from Bard and was planning to use it to drive to Marfa, where he had an internship. I felt like I was passing a baton. But exactly what kind of baton was it? Few things in the popular imagination are as symbolically loaded as cars. Or as guitars, for that matter. But let me start with vans.

The first one was our family car, by which I mean to say, my mother’s van. She named it Ruby Blue. The exterior was tomato-soup-colored and the inside was pink. My older sister was fifteen at the time, which would make it 1980, and had kissed a man twice her age on a bed in the back. He owned the local bar. I remember my mother pulling him out of the van by his hair and my sister scampering away in embarrassment. Sometimes when I remember it, I’m the one on the bed with the bar owner; perhaps he touches my face and tells me how beautiful I’ll be when I grow up, the kind of woman who will make men fall off their bicycles. He did say that to me once. What I see clearly now is the cartoonish way he was expelled from the van—headfirst—by my mother’s clenched fist. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the van was a feminist space.

The enclosure of a van is security to some and a threat to others. It’s a space that seems to exist outside law and convention. I took pride in its wildness, in how feral I became when I traveled in my van. I didn’t need anybody or anything; in my van, I was self-sufficient. If I stayed with a friend, my van was my bed. I could leave at any time of the night without waking anybody up.

When I drive, I’m simultaneously inside and outside. The interior driver is safely strapped into an impenetrable private bubble, while the exterior driver navigates freely through the world and covers long distances. If I’ve been driving for a long time, I turn off the radio so I can hear the engine. What I’m listening for are problems, a misfiring piston or a metallic scrape. When I stop to pump some gas, I like smelling the exhaust fumes and how my ass vibrates for a while after the motor’s been cut.

I’ll probably die one day in an automobile accident. It will be raining and dark with low visibility. Construction on the road forces the four lanes of traffic to converge into two, and each oncoming car splashes another wave of dirty water against my windshield. Their headlights blind me and we scream with our horns. I’m hit head-on but I don’t try to swerve—instead, I use my hands to protect my face.

My father died in 2013, the week before my winter break from teaching, which is when I usually go on a road trip to take photographs. I decided to go anyway that year, leaving the preparations for my father’s memorial to my sister. I stopped the car only to sleep or to pee or to write emails inviting people to his service. I don’t think I took a single usable photograph.

The van was a way to navigate through my grief. I imagined I was driving away from pain but in fact it filled the four corners of my vehicle. I drove the long way to LA, through the South and along the Mexican border. I listened to the same CD the whole way, on repeat for the entire month. It was in the stereo when I started the van and I never bothered to take it out. The CD was by a guitarist, someone I’ve had infrequent but periodic hookups with over the past twenty years; he’d given it to me four years earlier, the last time I’d seen him.

He’s something of a genius improviser in the way he builds a melody and shatters it open. His music feels interior since it registers emotionally, but also exterior because, in order to structurally pull apart a song, there must be distance. A tune might turn itself inside out, negate itself, and devolve into atonality. Listening, I tumble into the lacuna that had once been a song. Later, I learned to recognize particular strains in his songs from the music of his teacher, a Haitian classical composer who, among other things, mimicked the sounds of voodoo drums with his guitar. You can hear it in the rumble of low chords oscillating back and forth, like jumping from your left foot to your right, the strings loose and dirty, slurring as if toothless and drunk. He plays on his own on this CD, and the sound of solo guitar was especially affecting in my state of mind. His guitar became my soundtrack as I drove west and by the end of the trip, I was in love with him. We’ve been involved ever since. Until last month, when he broke up with me. Again.

I never felt comfortable photographing him, so I made pictures of his guitars. A guitar can stand in for a woman’s curved form, or it can be phallic—increasingly so the lower it hangs on a torso. I wanted to unravel the myths surrounding guitars, even if I only cared about the ones that belonged to my Guitarist. I photographed his guitars in order to fix them in my own fantasy.

It’s necessary to traverse a fantasy rather than go around it, if you want to unfasten its hold on reality. By moving through it, you have the possibility of understanding what it’s made of. This isn’t my idea; it’s Žižek’s, or Lacan’s, or somebody’s. Anyway, if you can bear to go the whole distance, you’ll discover there’s a void at the center, a huge abyss of nothingness, and that the journey is compelled by nothing more than cheap, everyday props and disposable promises. It’s a little like driving a car, or soloing on guitar—once it’s over, it’s hard to know why you bothered. Vans are hollow inside and so are a lot of guitars, volumes of empty space designed to amplify sound or capacity.

I’ve had a few vans, but by the time I got this last one, I knew exactly how I wanted it. I designed the interior especially for road trips. The bed doubled as a shelving unit for camera gear; it had a bookcase, cupboards, and hardwood floors. The man who built it built houses and used fancy scrap lumber, birch and cherry. He also played the guitar.

Thoreau’s transcendental philosophy underlies much of my motivation for driving, even if I often find his writings annoyingly self-righteous. Nevertheless, it’s all there: my attraction to natural settings, as though going deep enough into a forest means I can walk into a time before I existed; my sense that isolation and self-reliance can solve the messy problem of other people. The part that most deeply resonates with me is his cabin. When I drew up the plans for my van and outfitted it with the things I would need, I felt complete in a way that’s hard to quantify. Yes, I do happen to have a Phillips-head screwdriver, a pee jar, a cast-iron pan, a copy of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, tampons, the Rand McNally road atlas, peanut butter, and a memory-foam mattress pad. But it’s more than that, more like the love a turtle has for the color, rather than the usefulness, of her shell.

Maybe Thoreau is only a libertarian, claiming a freedom within the margins of his privilege. Haven’t we all heard the story of how, during his two years at Walden, he would walk the four miles home every day for his mother’s fresh-baked cookies? Think about how Virginia Woolf’s “room of one’s own” differs from Thoreau’s cabin. If a woman’s role in society traditionally demands her subjugation, then it might be wise for her to withdraw. Woolf writes of the necessity of “killing the angel of the house,” which splits me in two when I see my eleven-year-old’s body, damp and limp, innocently tangled in his sheets. What about my own responsibility to stick around? After all, someone has to bake the cookies.

After my father died, I walked through his house and photographed his things with my iPhone. I felt creepy doing it—not that he would have minded, but sometimes what a photograph shows isn’t nice. He lived in deprivation and poverty. An angry stoicism marked his house, from his duct-taped orthopedic shoes to the DO NOT RESUSCITATE order taped over my son’s drawing of a train on his refrigerator, aged by speckles of food. The walls were yellowed from nicotine and furry from dust stuck on grease. There were carefully crafted models of Mussolini-era bombers and a table for tying flies: fighting and fishing. I never used the photographs for anything or even showed them to my sisters. But I think taking them changed how I photograph.

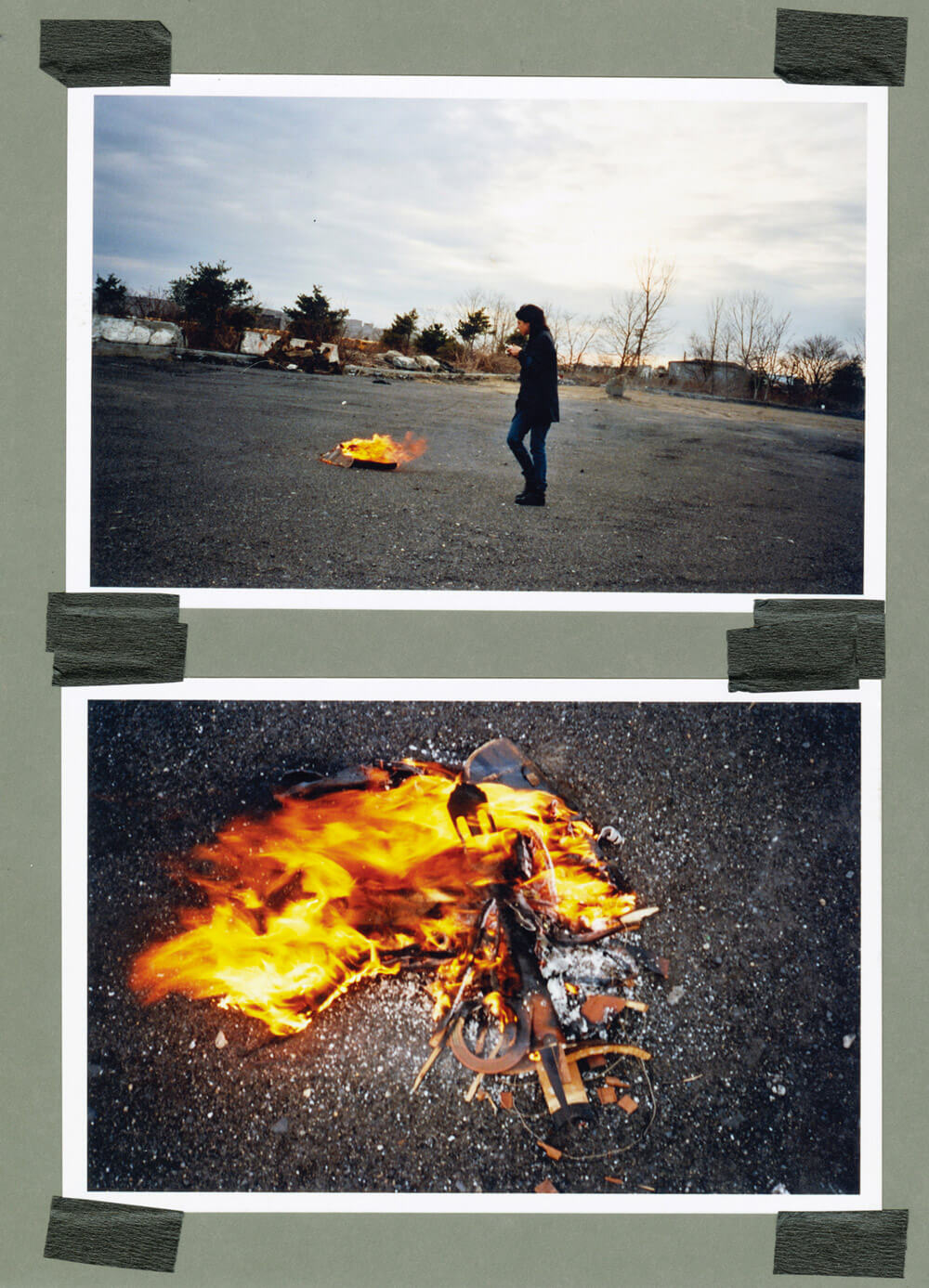

The Guitarist left a guitar at my house so he would have something to play on the rare occasions he came over. It was a beater—the wood had lost its tension and the bridge kept popping off—but he couldn’t bear to throw it away because it had been a gift from his teacher. I didn’t break the guitar out of anger alone. My aggression was tentative, even self-conscious. I only cracked the face at first, careful to keep the body intact. As the weeks went by, I took more liberties. But destroying the guitar was not some easy metaphor. I broke it into pieces because of a trajectory I had set in motion with the first photograph I took of it. I had been photographing his guitars to know what they were made of, to understand them as physical objects in the world, with a finite capacity for distress, and a fixed point of dissolution.

By the time I was done with it, the guitar was small enough to fit inside a tote bag. I brought it to a vacant lot to burn and remembered a story the Guitarist had told me about his teacher. I’ll call him George. In the late forties, George left Haiti with his wife and moved to New York in order to pursue a career as a composer. He told her that he wouldn’t have children with her, also because of his career. The story goes that, while he slept, she crept into his room and tried to cut off his fingers with a pair of scissors. George managed to keep all his digits and later became the father of Haitian classical guitar. But I’m not thinking about him now, I’m thinking about her. I wonder if she was enraged when she held his hand in hers, or merely being practical.

I’m shopping for another car now—a used economy compact, nothing to call home, just a car like any other car. My van had become a container that shaped not only what was inside it, but also what lay beyond. I sold it because it felt like a played-out story, in which freedom had become synonymous with isolation. I need to travel, but there are a lot of different ways to go. Even though I’ve shed my cabin, I’m keeping the wheels.

In William Faulkner’s Light in August, Lena Grove travels in pursuit of her baby’s father. She continues her journey long after it’s clear that no father will materialize. He’s not the reason she goes on, just her excuse for living on the road. “My, my. A body does get around,” she sighs over and over again.

Justine Kurland is a New York–based photographer. Her debut monograph Highway Kind, published by Aperture, was released in the fall of 2016. She is represented by Mitchell-Innes & Nash gallery, New York.