Ingestion / How to Boil an Egg

Cracking the ovum philosophicum

Mats Bigert

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

In 1995, when fifty-year-old Malcolm Eccles was diagnosed with terminal bowel cancer, he decided that he would leave his wife Brenda a memento she would never forget. There was one thing she couldn’t cook and that was eggs. Always mistimed, hers would come out either too hard or too soft. Malcolm engaged a specialist glassblower in south London to make a foot-tall hourglass in which a portion of his ashes would be encased. Interviewed by the Independent in 1997, just after Malcolm had passed away, Brenda commented: “It’s just what he wanted. I can see him now laughing his head off at me. He said he had worked so hard all his life and enjoyed it, so he couldn’t see why he should stop working when he was dead. … He said: ‘At least when you turn me over it will make you smile rather than make you cry.’”

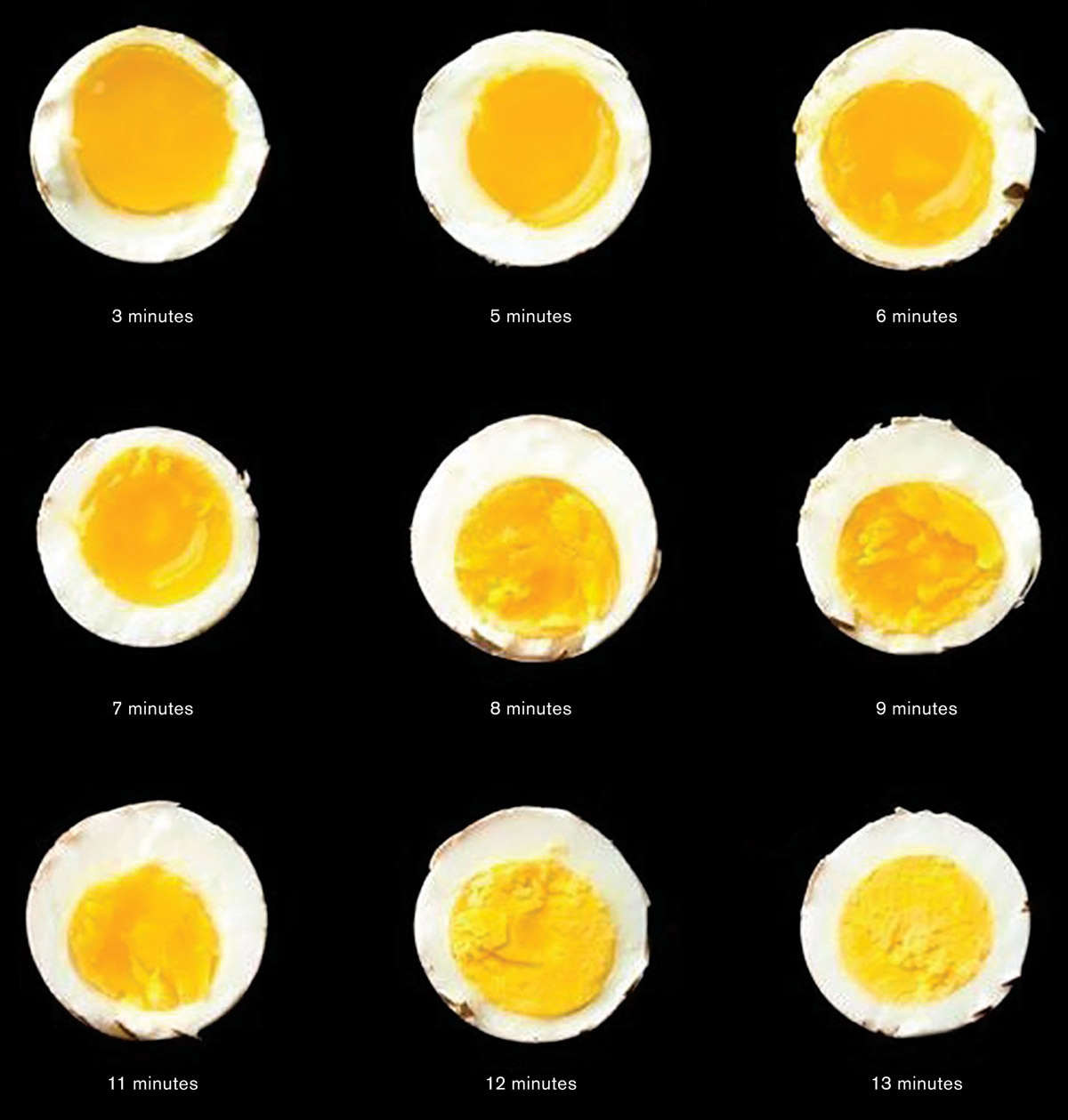

The art of boiling an egg doesn’t have to be a story about life and death, but for many of us it is a serious business that needs some practice to perfect. When I was growing up, my mother boiled our eggs until they were hard as stones, with a sulfuric green aura around their yellow innards. It was Sweden in the 1970s, and in my world, eggs were eaten that way. Often presented as part of a smorgasbord, they were halved and then topped with even smaller eggs squeezed out from fish behinds. But when I had to begin feeding myself, my awareness of the diversity of how eggs could be ingested increased. The first time I ever ate soft egg yolk, however, was a deeply traumatic experience. It wasn’t a boiled egg but a fried one—sunny-side up—presented on a slice of rye bread. After munching into the white corners of the egg, I approached the yellow center. I made a bold decision and took the whole yolk in one ravenous bite. As the sandwich, which I had bought at a canteen, had probably spent most of the day in a covered plastic container awaiting its eater, it had developed a thin coating and its convex geometry adhered perfectly to my concave upper palate, like glue. I had to scrape it out of my mouth with a spoon.

But this experience somehow cracked the ovum philosophicum—the alchemist’s “philosophical egg.” A mystical, gooey substance, which I had only ever encountered in a solid form hermetically sealed in its oval container, was now leaking out from its vessel. It was death, and rebirth. My mother’s hard-boiled egg-stone had metamorphosed into the philosopher’s stone, changing any substance it came into contact with, including my upper palate.