I Put a Light in the Milk

Suspicion in a glass

Jeff Dolven

François Truffaut is ready to move on. He is halfway through his series of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock, which take up the British director’s films in roughly chronological order. The two have been talking about Suspicion, from 1941, the casting of Joan Fontaine, the debates over the ending, the disappointing decision to shoot in a sound stage rather than on location. But Hitchcock detains him over a last detail:

A. H. By the way, did you like the scene with the glass of milk?

F. T. When Cary Grant takes it upstairs? Yes, it was very good.

A. H. I put a light in the milk.[1]

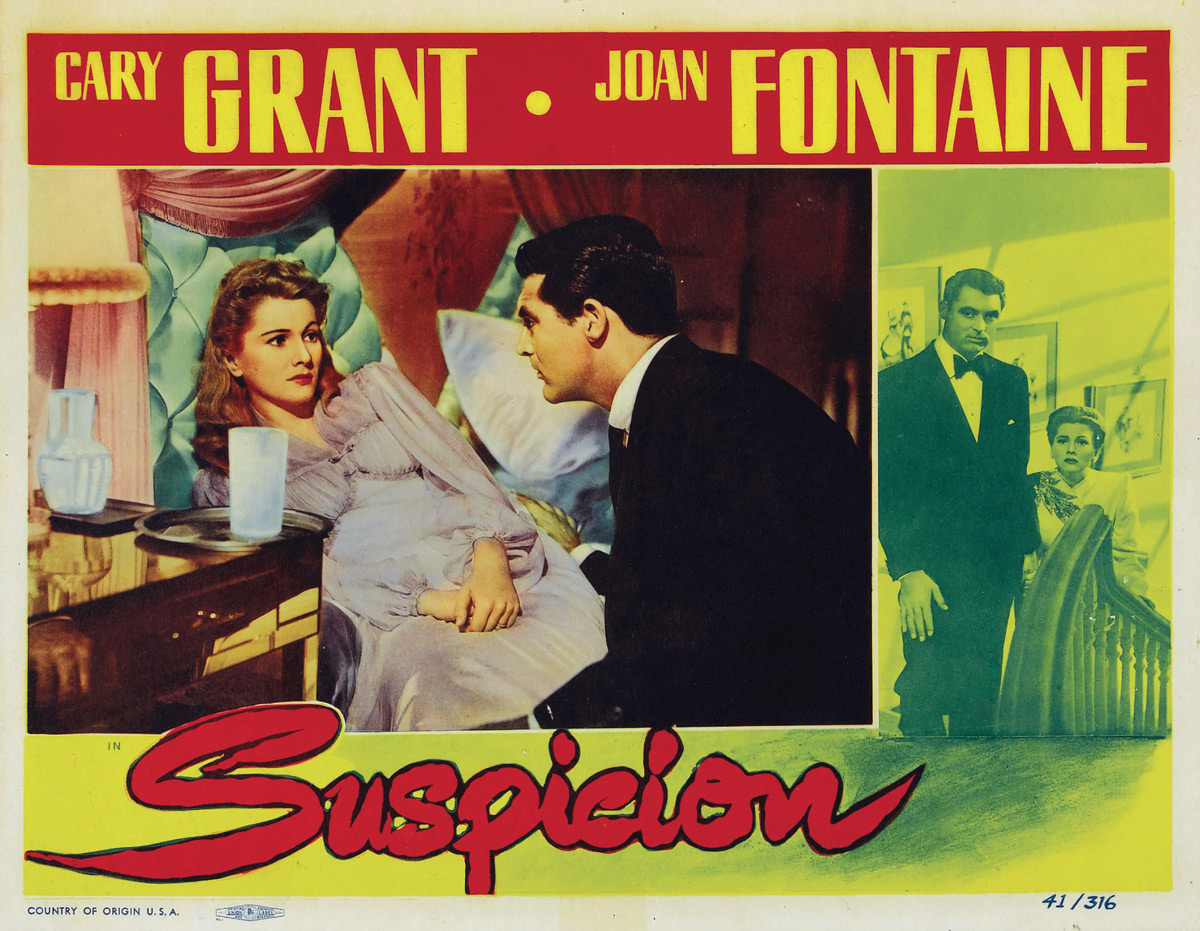

Anyone who has seen the film will have to agree with Truffaut’s assessment. Cary Grant, playing the charming bounder Johnnie Aysgarth, enters a dark foyer in the grand house that he and his new wife Lina cannot afford. The camera follows him from above as he crosses the floor and mounts the stairs, carrying a tall glass of milk on a silver tray held casually, one-handed, just above his belt. He is lit from behind, his face in black shadow, but the milk—the milk glows like a torch, the moving center of the scene, and as he approaches the waiting camera its white glare almost fills the screen. It is a beacon, a sign. But the reader coming upon the still image for the first time, and the moviegoer who has been following the story for ninety minutes, will be equally unsure: a sign of what?

For the reader, a sketch of that story is in order. Grant’s Johnnie meets Fontaine’s Lina on a train, where he persuades her to help him through a little contretemps about having a third-class ticket in a first-class compartment. The next time they see each other, it is at a fox hunt, where Johnnie, in ascot and bowler, carries himself with reassuring savoir faire. Next, he is at her doorstep, in the company of her hunting friends; then he appears again, by himself; in short order, and against the wishes of her father, the upright General McLaidlaw, they are married. It does not take long for Lina to realize what the audience already well knows, that Johnnie has no money of his own, and their lavish new life is lived in expectation of her inheritance. At her urging, he does take a job … but he is soon discovered to be borrowing from the till. The general dies … but when the will is read, they learn he has cut his daughter out. There is a scheme with Johnnie’s friend Beaky to invest in a cliffside real estate development … but Beaky dies mysteriously in Paris. Johann Strauss’s “Wiener Blut” waltz, the leitmotif of the couple’s infatuation, modulates from major to minor in the background. One morning, reading the mail while her husband is in the bath, Lina discovers that he has made inquiries into the terms of their common life insurance policy. Not long after, a mystery-writer neighbor tells that Johnnie has been asking about the relative merits and accessibility of undetectable poisons.