Ingestion / What’s for Dinner?

Painting the head of the table

Leonard Barkan

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

Suppose that you were a lonely analphabetic with no religious education—the year could be 2017 or 1617, it doesn’t matter—and at the same time zealous for initiation into the narratives that the New Testament offers by way of instituting the Christian faith. You are fortunate enough to have access, whether by magic carpet or internet, to the world’s treasury of sacred paintings. And from this rich sampling you set yourself to deduce the leading features of a creed that, from humble beginnings in Galilee, managed to spread its good news throughout the world.

You might well conclude that it was all about the lure of dinner parties.

If Jesus is sitting with two other guys and staring meaningfully at the bread, it’s the Supper at Emmaus. If He is seated at a heavily laden banquet table in a big crowd and a woman is washing his feet, it’s Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee. If He is seated at a similar table but no woman is washing his feet, it’s Christ in the House of Levi. If He is part of a domestic scene with one woman at his feet and another woman cooking, it’s Christ in the House of Mary and Martha. If He is surrounded by a bunch of his man friends and there is bread and wine on the table, it’s the Last Supper. If He is holding out loaves with one hand and fishes with the other, it’s the Feeding of the Five Thousand, or it might be the Feeding of the Four Thousand. The bottom line is that He did a lot of feeding.

All of which suggests that we ought to pardon our hypothetical novice in matters Christian if she comes to believe that this is some kind of gastronomical eating club. She’d be quite mistaken, of course. The truth is that it’s not Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John who have proclaimed this culinary sect; it’s the painters following in their textual footsteps. For visual artists, whether medieval, Renaissance, or working in any other age, the project of depicting, say, the virgin birth, one God in three persons, or transubstantiation versus consubstantiation, is something of an uphill struggle, and not always easy on the spectators either. On the other hand, who doesn’t like a dinner party? And so it comes to pass that Christianity on the walls of museums and even of churches may appear out of all proportion an affair of the dinner table.

These same cuisine-happy artists, as it turns out, were not content with merely depicting the consumption of meals as the Bible specified them; they insisted on pushing the envelope. Bread and wine are hardly sufficient for many a painter of the Last Supper, so their Holy Tables groan under the weight of what we in Manhattan used to refer to as a Great Neck bar mitzvah. Dozens of Madonna and Child paintings are decorated with a quite extraneous piece of fruit, whose variety—apples, grapes, pomegranates, cherries—suggests that it doesn’t amount to a piece of sacred allegory so much as a means to enable viewers contemplating the Holy Mother and Child to fix their minds on something juicy at the same time.

Then there is the case of Herod and his feast. The biblical account—as sketchy as Bible history tends to be—needs some decoding. Herod Antipas (not Herod the Great of the Slaughter of the Innocents fame, but his son), hearing for the first time about Jesus’s ministry, imagines that the new itinerant prophet is in fact the old one, John the Baptist, who has come back from the dead. At which point the whole story about Salome and the severed head gets introduced as a flashback informing us how John came to be dead. The scene in the biblical text is not a meal at all but rather a birthday party, which Herod has thrown for himself. This is the occasion when his stepdaughter provides the fatal entertainment.

On the premise of this celebration, gastronomic extravaganza erupts among the painters. As early as Giotto in the beginning of the fourteenth century, Herod’s party becomes a grand occasion for banqueting. The biblical dance is taking place, but the largest share of picture space is devoted to a richly appointed dining room, at the center of which, on a pedestal, we see the table decorated with dishes and napery. An out-of-scale viola da gamba player is presumably on the scene in order to accompany Salome, but his placement is such that he could just as easily be construed as providing background music for the feast.

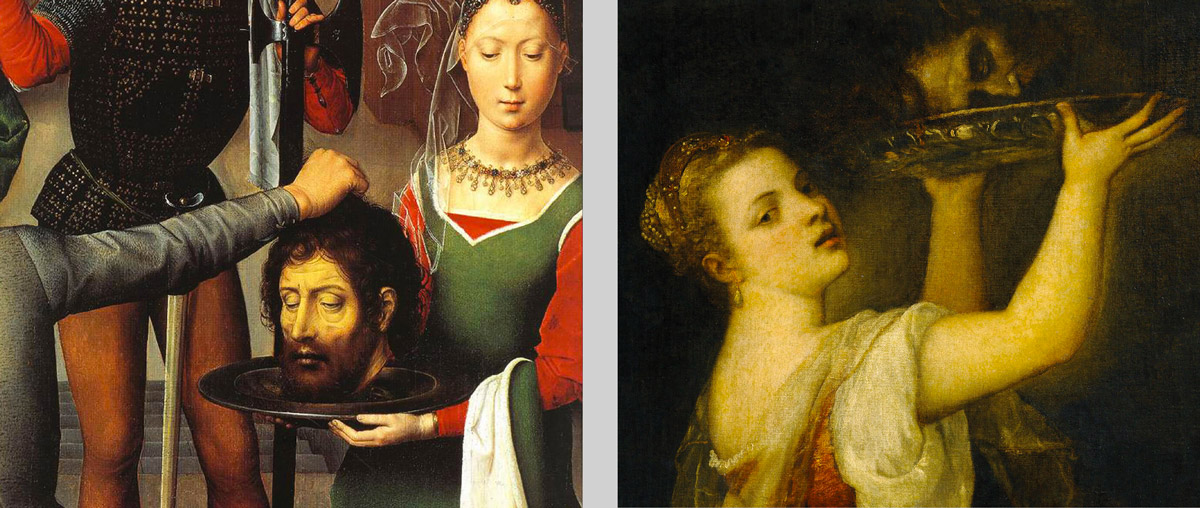

By the time of the High Renaissance a hundred and fifty years later, banqueting has all but swallowed up the story. Both Ghirlandaio and Filippo Lippi seize the occasion for the display of the most grandiose all’antica architecture, appropriate to Herod’s status as a dependent of the Roman empire and designed along sharply perspectival lines. No expense has been spared on these two occasions of feasting: gleaming linens, elegant service pieces, the diners themselves in their finest attire. Ghirlandaio goes so far as to include a wall of gleaming gold and silver chargers, not being used for service, an act of conspicuous consumption along the lines of the advice given to Renaissance Italian princes that, while some dinnerware should be both beautiful and useful, other pieces should be used “for ornament and elegance alone.” In both these late quattrocento frescoes, then, the principal business of the biblical story is overshadowed by the wish to present the latest and grandest fashions of banqueting.

Yet considering the outcome, there is bound to be something strange at this particular dinner. More of the backstory: back in the long-ago days when the Baptist was stirring up trouble in Judaea, Herod had been something of a protector, finding the prophet to be “a righteous and holy man” (Mark 6:20). But now—or rather in the more proximate past—John, with his tendency toward religious fundamentalism, has been declaring that Herod’s marriage to his own brother’s wife (the brother not yet being dead) is illegitimate. The wife, Herodias, has taken that judgment very ill. And she is one to carry a grudge.

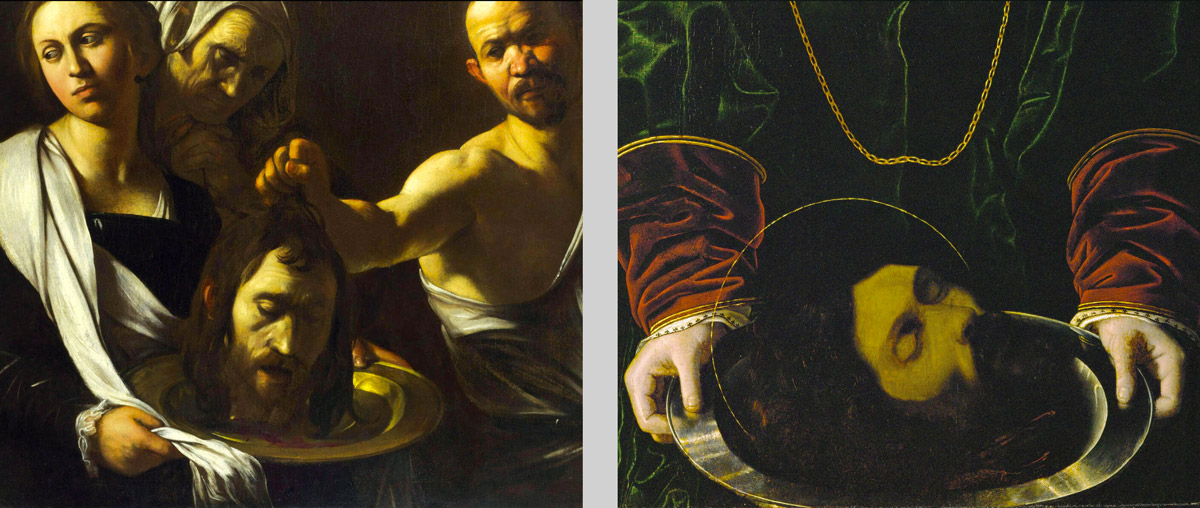

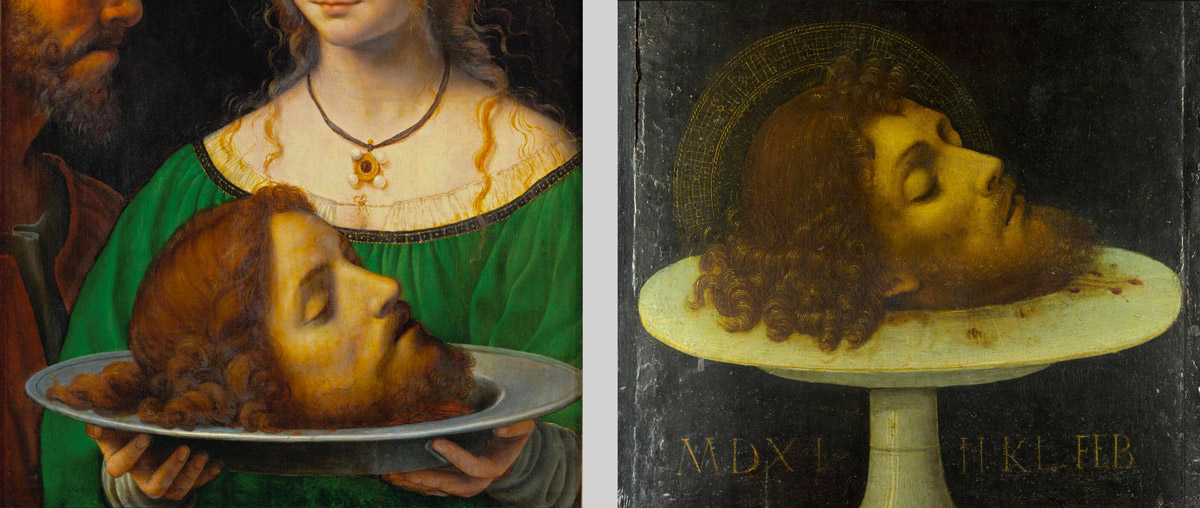

Back to the bare-bones biblical narrative, then: Herod has a birthday; Salome dances. There is no banquet, no china, no silver, but there is something quite unexpected. Salome dances so alluringly that Herod offers to grant any imaginable wish, even, he says, half his kingdom. The girl herself shows no signs of having any wish in mind, but defers to her mother. Herodias, in no state of uncertainty at all, seizes her moment of vengeance and demands the head of John the Baptist. In Matthew, we hear this only in Salome’s voice; in Mark, Herodias says it and Salome repeats it with a difference. In either case, it is Salome who frames the crucial form of the demand: the head of John the Baptist on a platter. Why on a platter? This curious supplement to the request for beheading has, so far as I can tell, excited rather little commentary, though it would seem to beg for exegesis. It does not appear to be a linguistic problem: the phrase itself, (in the Vulgate, in disco), is straightforward and gets translated variously as on a trencher, a charger, a platter, or a plate. In short, the kind of flat disk on which food is served.

What kind of intensification, whether arising from Herodias or magnified in Salome’s transmission of the demand, is this? Not just dead, but decapitated, the head not just severed but on display, not just on display but subject to the formalities of a social occasion—indeed, the sort of occasion at which Salome has performed the dance that has set the whole chain of events in motion. Now that the head is to be presented on a platter, it may be less of a surprise that the occasion tips from a dance recital to a dinner. And, through the magic of narrative prolepsis, propelled by Salome’s further specification that it be done at once (, protinus in the Vulgate), it turns into the kind of fiction where everything can happen simultaneously. Before the evening’s festivities are over, the Baptist can be located in his prison cell, beheaded, and, as it were, served. Perfect for a medium like painting, in which long stories have to be displayed as though they took place in a single moment.

Though the artists may have imposed dinner upon a foodless biblical birthday party, scripture nonetheless was handing them a piece of narrative that cried out for the imagery of the feast, albeit of a perverse kind. Whatever the extent of dining paraphernalia in the visual production of artists from Giotto to the Renaissance, the Baptist’s head becomes the evening’s culinary pièce de resistance. The figure of the inclining servant, in banquet array, offering up the grisly platter in full view becomes quite canonical. It is exactly the posture for displaying to princely diners some highly confected piece of culinary art. Indeed, it fulfills the traditional Renaissance demand for elaborate visual presentation at grand dinners, more important even than the flavor once the food was tasted. The motif makes an appearance as early as Giotto and gets frequently replicated thereafter. Ghirlandaio places the kneeling servant discreetly at some distance from the diners, but Filippo Lippi erases that distance and has a female figure—not, I think, Salome, who is dancing off to the left—delivering the macabre menu item directly in front of the banquet table.

Is it, as I suggested in enumerating the representation of all of Jesus’s feasts, that the painterly lure of the banquet extends so far as to make John the Baptist a cannibal sacrifice? Or was the Bible itself, with that fatal phrase “on a platter,” indulging in the gruesome business of conflating dinner with decapitation, leaving the artists merely to realize in paint what lay implicit in words? Or am I just being a modern revisionist with his mind on the bizarre and the gastronomical?

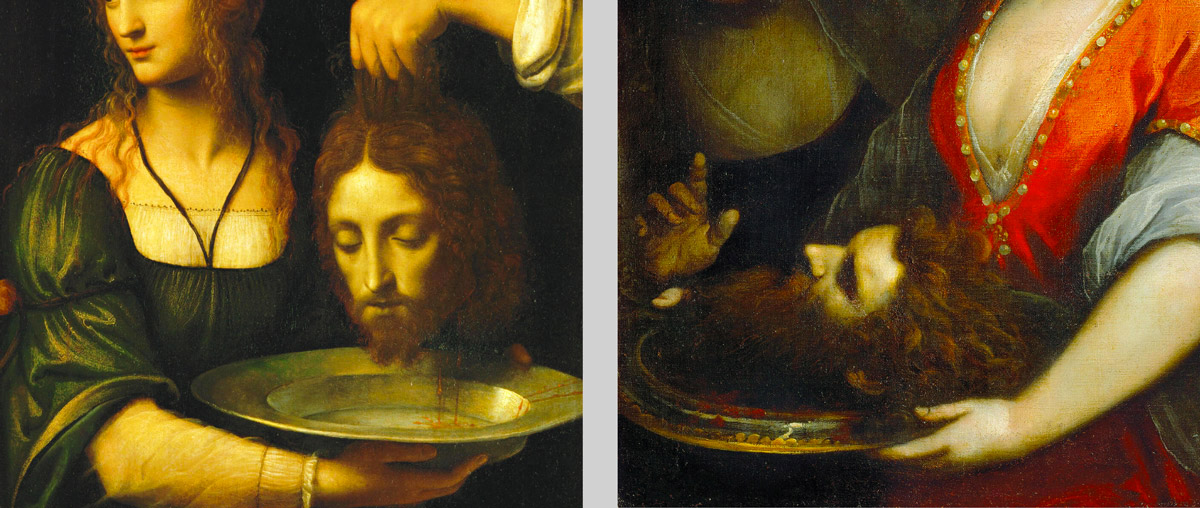

One artist, transalpine and a few decades later into the Renaissance, may suggest some consciousness of what is at stake in this piece of startling visuality. Lucas Cranach was a painter of very considerable versatility, as comfortable with nude Venuses as with portraits of Luther, a maker of serious altarpieces but also capable of pictorial play, like his Fountain of Youth, where old women are transported via wheelbarrow to a swimming pool and emerge young and beautiful on the other side. Whether it was part of his piety or his love for the bizarre, he seems to have had a special taste for sacred beheading, as witness his numerous versions of Judith and Holofernes as well as his several Salomes. Indeed, the beautiful young woman holding the head of a decapitated greybeard is almost a Cranach signature piece.

Cranach’s full-scale Feast of Herod is a bit different, though. As with many of his works, we have multiple versions, some of which may be even posthumous studio work undertaken by his son. The painting in Frankfurt is widely, and I think correctly, held to be autograph. As one might expect from its northern origins, the painting’s subject here is not grand princely dining but more like a family affair among the well-heeled bourgeoisie. The linen is simple, the table appointments minimal. No curtsying liveried servant presents the severed head but, one presumes, Salome herself. There is no question, nevertheless, that this offering is (as it is with the Italians) to be understood in the category of dinner. Cranach in fact makes the point quite unmistakably. To the right of the dining scene, in perfect parallel to Salome with her platter, is another well-dressed figure who carries another platter. One is left to assume that he is part of a mealtime service sequence. On this second platter is a handsome array of apples, pears, and grapes. There is no missing the joke: John the Baptist is the main course; afterwards, there is fruit for dessert. Or in case we do miss the joke, we have the fruit server himself gazing outside the scene and making direct eye contact with us, as if to say, “Get it?”

Leonard Barkan teaches comparative literature, as well as the history of art, at Princeton University. His most recent book is Berlin for Jews: A Twenty-First Century Companion (University of Chicago Press, 2016), and his current scholarly project, about eating and drinking from antiquity to the Renaissance, is entitled Reading for the Food: Art, Literature, and the Hungry Eye.