Schloss Murnau, Hollywoodland, CA 90068

Tracing Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau in Southern California

Volker M. Welter

Castles, palaces, and stately manor homes provide the setting for many movies by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (1888–1931), the German silent film director who is today probably best known for Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922).[1] One of Murnau’s earliest films, The Blue Boy (1919) is set in Vischering Castle in Westphalia, which dates back to the thirteenth century. The Haunted Castle (1921) takes place in a neoclassical manor house, and much of the plot of The Burning Earth (1922) happens in and around a castle in Silesia. For Nosferatu, Murnau picked Orava Castle in Slovakia, a building with roots stretching back to the thirteenth century, as the site of Count Orlok’s home. And while the location of The Expulsion (1923) is only a crofter’s home on a faraway mountaintop, its isolation recalls the privacy of the moated Vischering Castle.[2]

Murnau arrived in California in early July 1926 and stayed there, except for a few months back in Berlin in 1927, until mid-May 1929. It was then that he sailed for Tahiti to shoot his last movie, Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931), returning to California by October 1930. A few months later, on 11 March 1931, Murnau died from the injuries that he had suffered in a car accident just north of Santa Barbara the previous day. For parts of his sojourn in California, Murnau made his home in Los Angeles in a building that contemporaries called a Schloss or castle. The edifice and its whereabouts have thus far remained unidentified and its importance and meaning for Murnau, accordingly, obscure. Considering Murnau’s profession, to move into a castle-like home seems to be another case of movie settings determining private architectural taste. However, Murnau’s fascination with castles harks back much further than his rise to one of Weimar Germany’s foremost movie directors. Castles held for Murnau private, positive associations rather than just being sites of inexplicable events or even horror, as some of his movies might suggest.

In 1917, during the Great War, the military unit to which Murnau belonged occupied near Verdun “a beautiful, but rather melancholy château, abandoned by its owners. … [Murnau] had the largest room in the château, arranged in perfect taste. Everything in it was clean and well-appointed; when you went to see him you forgot about the war, and made a polite and civilized visit.”[3]

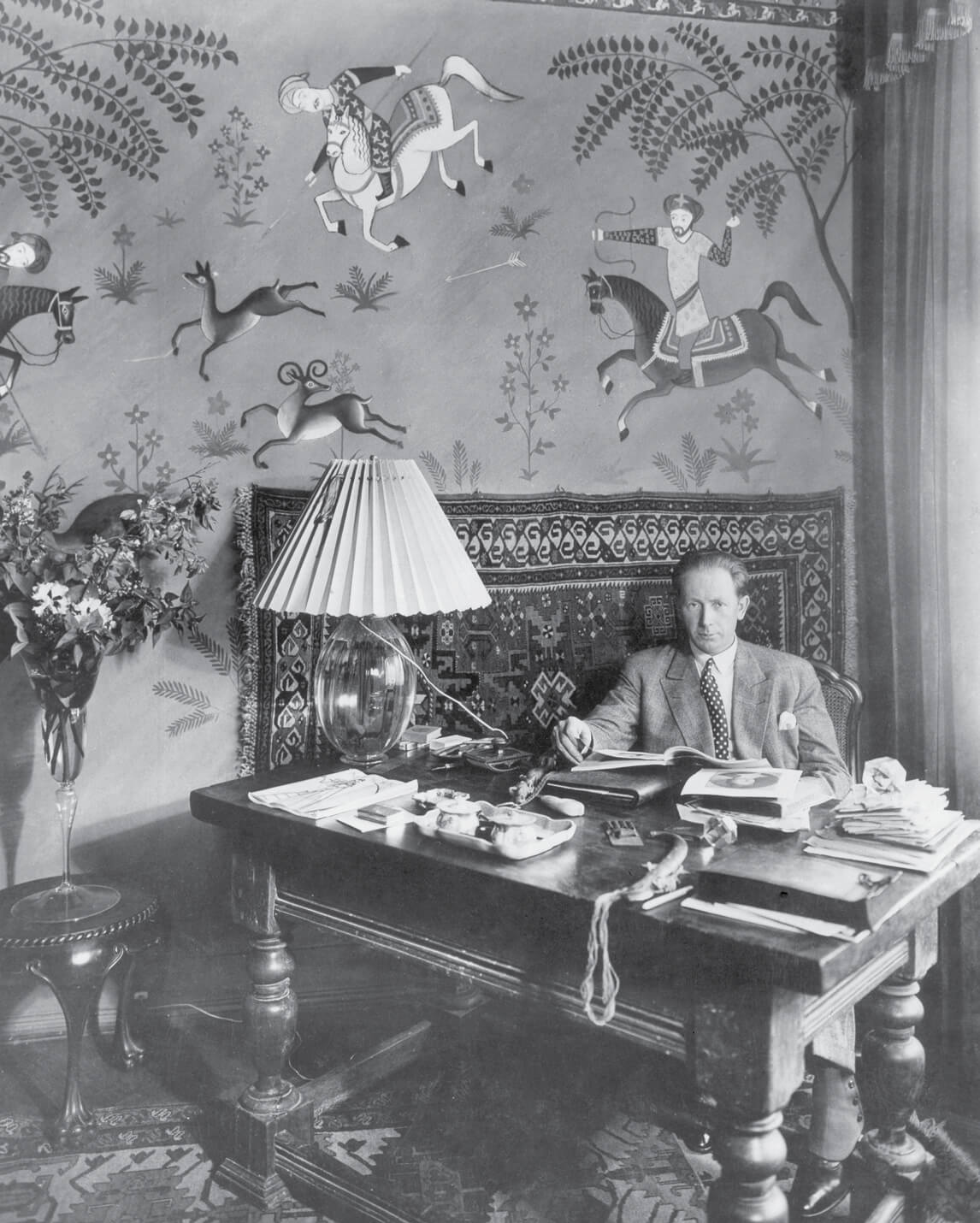

In Berlin, Murnau lived in a suburban version of a home that looked as if it had been lifted from a castle precinct in a walled medieval city. It was the family home of the poet Hans Ehrenbaum-Degele (1889–1915), Murnau’s friend, and perhaps lover, who had been killed on the battlefield. After the war, the poet’s mother had invited Murnau to stay in the home in Berlin’s Grunewald neighborhood and some time later transferred the property to her son’s friend. The building at Douglasstrasse 22–22a consists of two grand, attached townhouses, erected in 1901–1902 by the builder Wilhelm Körner, with Murnau occupying number 22. The tall, timbered roof, darkly paneled entrance hall, and the heavy masonry around the lower exterior walls may recall the past, but Murnau transformed his abode into a place evoking a future life elsewhere. Murnau lived there with the painter Walter Spies—a close friend, perhaps even another lover—and together the two men filled the home with artworks such as Asian marionettes and a mural depicting Persian-style hunting scenes that Spies painted in Murnau’s study; in short, objects and motifs telling of dreams about living elsewhere.

Giving in to his long-felt Fernweh, Spies (1895–1942) left Murnau and their mutual home in 1923, seeking a new life in Bali. Fernweh is the opposite of Heimweh (homesickness) or a nostalgia for the past. It afflicts upon its sufferers a heartbreaking longing for distant shores where they hope to find solace, if not a new self. Unsurprisingly, numerous Germans experienced that condition during the postwar years, though Fernweh’s history reaches back further to the Romantic period and beyond, as evidenced by many German fairy tales. Leaving for California was Murnau’s answer to his Fernweh, a longing he had probably felt for some time, changing his surname, as he did, from Plumpe, which in German evokes notions of clumsiness, to Murnau, a Bavarian village that had been home to an artists’ colony in the late nineteenth century. Ultimately, California could not satisfy Murnau’s Fernweh, as his later journey to Tahiti was supposed to take him even further, on to Bali, and back to Spies.

When Murnau returned briefly to Berlin in 1927, he asked the architect Dieter Sattler (1906–1968) to redecorate the interior of the Grunewald home in advance of his arrival.[4] Together with a mutual friend of both men, the cellist Francesco von Mendelssohn, Sattler created a historicist interior that fused sixteenth-century and baroque antiques, contemporary furniture, wallpapers, and soft furnishings, and paintings by Picasso and Cézanne into the image of a stately home that generations of owners had filled with objects and art works. The interior, as published in the fashionable magazine Die Dame, did not depict Murnau as in any way being interested in modernism in architecture and interior design.[5]

Fictional and real castles, stately manor houses, and visually rich, eclectic, and historicist interiors were the settings of much of Murnau’s private life. From early on they were associated for him with men and with lovers, and expressed his desire for privacy, as illustrated by his decision to set The Blue Boy in Vischering Castle. The title references Thomas Gainsborough’s 1770 painting of the same name, which plays an important role in the Dorian Gray–like plot involving a young man and a precious stone. In Germany’s gay circles at the turn of the century, however, prints or copies of Gainsborough’s painting were also used to signal their owners’ sexuality. Recollections of Murnau by friends and contemporaries often describe him as a quiet, polite, and mannered gentleman, an image more of a member of the landed gentry in a manor house than of exalted gay Berlin during the Weimar Republic. Finally, the stylistic distances these private homes and interior spaces kept from the modernist architectural-artistic concerns of the period express not a nostalgic longing for a past—either lost or out of reach—but emphasize Murnau’s Fernweh. Murnau’s Schloss in Los Angeles, a building designed in a French Normandy revival style, perfectly matched that longing.

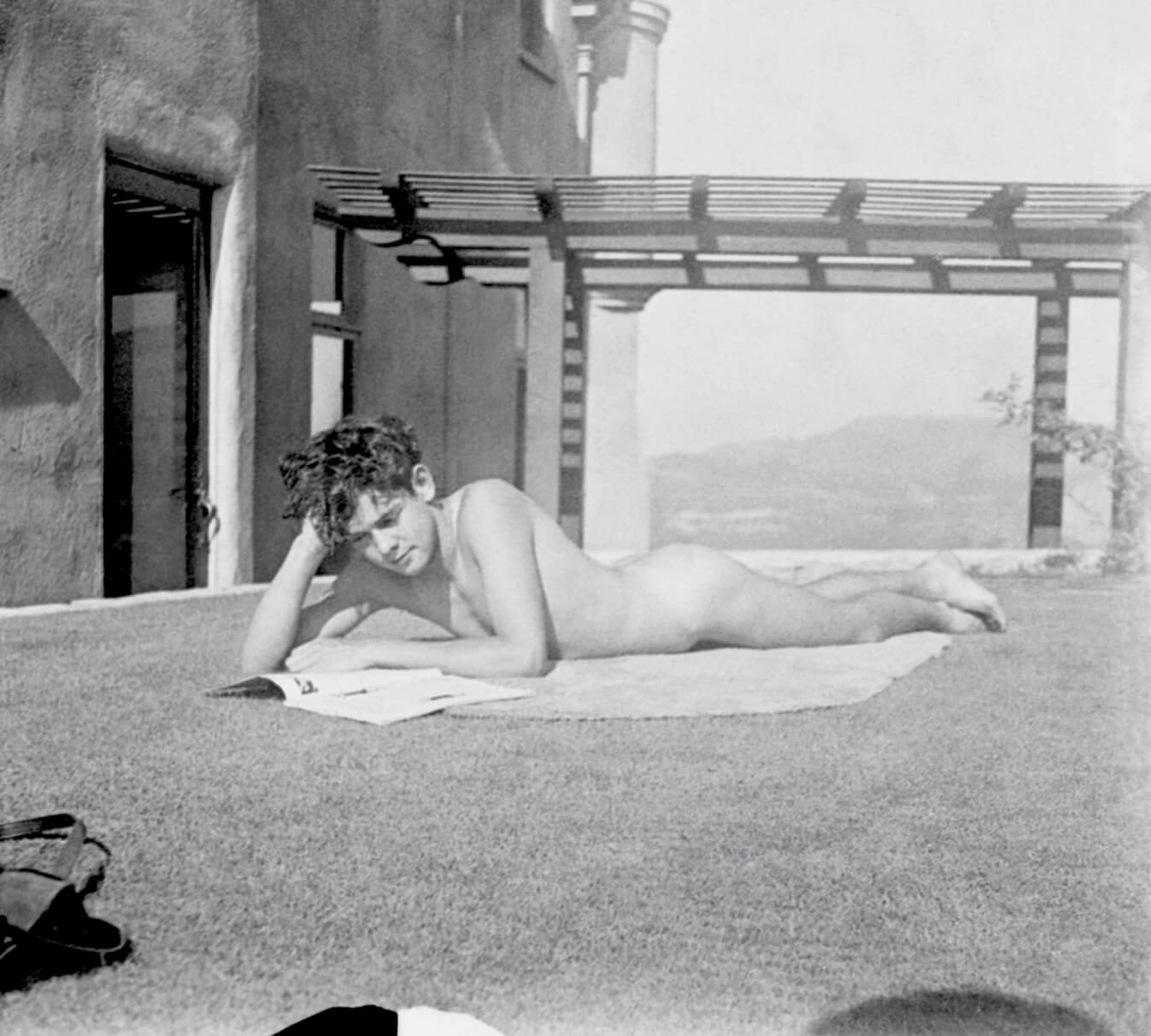

To trace Murnau’s private life in California, one has to go to Berlin. The Deutsche Kinemathek preserves in its Murnau collection a series of photographs of a young nude posing for Murnau and his camera in and around a house that is located in the hills above Los Angeles.[6] Subsequent to the publication of a selection of Murnau’s private photographs in 2013, the young man was identified as the actor David Rollins (1907–1997), whom Murnau considered, but ultimately did not pick, for a role in Four Devils, a movie he shot between January and May 1928.[7] In various interviews later in his life, Rollins told how Murnau, “a great friend of mine,” kept inviting him to his private abode.[8]

In the photographs, Rollins smiles in and out of a pool; inside the house he looks dreamily toward the outside, and appears in general at ease with his nakedness. “I was never ashamed of my body,” he states in one interview, even though, according to the interviewer, “Murnau’s desire to see David [Rollins] in the nude […] both puzzled and surprised him.”[9] Some of Rollins’s poses show the photographer’s knowledge of art history, a subject Murnau had briefly studied at university. Sitting on a small bridge over a pool, the model mimics, for example, Boy with Thorn, an antique sculpture now in the Capitoline Museums in Rome that, for gay men in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, also made coded reference to homosexual desire. Yet where in Los Angeles was this house in the seclusion of which Murnau could shoot such private, intimate photographs of a friend?

There is a description of a home occupied by Murnau that matches the location in the hills captured in these photographs. It comes from David Flaherty, a brother of the movie director Robert Flaherty; both men were in early 1929 in discussion with Murnau about shooting an independent movie in the South Seas, which would become Tabu. Writing in 1960, David Flaherty recalled that right after his return from Tahiti—where he had been on an exploratory visit for a different movie—Murnau asked him over for dinner. “Murnau lived alone with his servants in a castle perched on the highest hill in Hollywood. I felt flattered to be the only guest at the long table, which gave an eagle’s-eye view of the lights of Hollywood and Los Angeles far below.”[10]

With Flaherty’s topographical description of the house’s site in hand, and by examining the edges and corners of the house visible in Murnau’s private photographs, I searched for “castles in Hollywood” online, and was soon able to identify the edifice as standing in the Hollywood Hills at 2863 Durand Drive. Photographs by Murnau of the entire house, which I eventually saw in his archive in Berlin, confirm this identification. Locals know the building as “Wolf’s Lair,” perhaps a fitting name for a home temporarily occupied by a German.

Further up the hills rises the “Hollywood” sign. In 1923, when it was first erected, it read “Hollywoodland,”[11] flashed annoyingly with thousands of light bulbs, and advertised the hillside development below where engineers were cutting roads and leveling building sites. Among the developers was Leslie Milton Wolf (1894–1972), who acquired lots 1 to 4 in Block 2 of Tract 6450, numerical co-ordinates that translate to a triangular piece of land wedged between Durand Drive and Wetona Drive. There, Wolf erected as early as 1924 a two-story building of nine rooms in a French Normandy style, which meant plenty of corner turrets, steep roofs, and an irregular roofline. Access to the isolated spot was via Durand Drive, where a round tower marked the entrance to the lot. Already by December 1926, a second tower had appeared at the rear of the house.[12] And by March 1927, Wolf was expanding the original short entrance tower into a full-blown gatehouse to accommodate servants and automobiles. Beside the now-tall tower, mock medieval tracery and a dovecote were cramped underneath an elongated, hipped roof in a French castle mode. The gatehouse is visible in some of Murnau’s photographs, dating his tenancy in the castle to after the completion of the former.

Two more photographs in Murnau’s archive show the swimmer (and later Tarzan movie star) Johnny Weissmuller with and without Murnau in the garden of Wolf’s Lair.[13] According to the Los Angeles Times, Weissmuller visited the city from 17 to 24 May 1928, which would place Murnau in the house in early spring of that year, around the time when the filming of Four Devils ended.[14] Taking into account that Murnau had arrived back in the US in early October 1927, he may have moved into Wolf’s Lair as early as late 1927. Assuming David Flaherty’s recollections are chronologically correct, the dinner with Murnau happened at the earliest after 15 February 1929, the day when the SS Tahiti, on which Flaherty traveled, arrived back in San Francisco.[15] This would put the dinner most likely toward the end of Murnau’s residency at Wolf’s Lair, but absent further sources, the date of his leaving the Schloss currently has to remain undetermined. That the Los Angeles City Directory from 1929 lists his address as 9 Laughlin Park only adds to this uncertainty, especially as it is neither known when the information for the directory was compiled nor when the volume was published.

Erhard Bahr remarks in his book Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism that as “a city without historical memory,” Los Angeles has always attracted those who wanted “to escape history.”[16] Many of the émigrés escaping (National Socialist) history in the 1930s and 1940s, however, could not find a life without history in Los Angeles, despite Southern California’s reputation, because they in fact missed the very historic background against which they had habitually debated the merits of modernism. But for other immigrants, Murnau for example, this absence was neither cause for lament nor a shortcoming, but the attraction of California.

Already in 1827, Goethe had written “America, you’ve got it better” in a poem about the carefree living that came with freedom from history and remembrance. Still, the poem ends with a stern warning not to re-erect the past, as might happen when a young artist sets out to write poetry: “Protect him […] From tales of bandits, ghosts and knights.”[17] Others, such as the American landscape painter Thomas Cole, severed any reflexive linkage between old stories, historic buildings, and references to the past. In his 1836 “Essay on American Scenery,” Cole points out that the associations that come to the mind of an observer of contemporary American landscapes generally have to do with the present and the future, but not the past. “Looking,” Cole writes, “over the yet uncultivated scene, the mind’s eye may see far into futurity.” As an example of the associative images emerging from that distant future, Cole imagines that “on the gray crag shall rise temple and tower”; thus, historic building types like castles and palaces morph into symbolic images of the future.[18]

In Berlin during the 1920s, when architectural modernism took off, Murnau never succumbed to the lure of naked cubes, horizontal windows, flat roofs, and other signs of architectural modernity, and the life that accompanied it—a life Walter Benjamin once described as one without traces insofar as it was conducted between hard, shiny surfaces. But Murnau was not ignorant about the changes modernity wrought on the perception of (architectural) space and the human life conducted within it. Just the opposite: as early as 1924, he had discussed how the moving, rather than static, movie camera would make visible “the symphony of the melody of [human] bodies and the rhythm of space.”[19] As an art historian, however, Murnau also knew that new techniques of camera usage were mere means for creating images. His trust in the power of images was so strong that he predicted in 1928—wrongly—that “the ordinary picture, without movietone accompaniment, without color, without prismatic effects and without three dimensions, but with as few subtitles as possible, will continue as a permanent form of the art.”[20]

In the same article, Murnau reflected on contemporary America’s love affair with war movies, which made the country appeal to him, “the most extreme pacifist,” because of his longing for romance. The latter, in turn, also sheds light on the fascination castles and manor houses held for the movie director. Murnau recognized in America’s voluntary entry into the Great War a “demonstration of bravery, loyalty and martyrdom, each of these attributes a thread in the cloth called romance.” Postwar Europe was no longer capable of seeing that romance, which, however, had not ceased to exist, even during the darkest time of warfare.[21] Murnau captured that romance when he arranged his room in the occupied French manor house into an image of a time when war was over. He experienced it again, when he lived in his Schloss in Hollywoodland, and he lived the romance whenever he created a private home for himself.

Finding the site of Murnau’s tragic accident on California’s Pacific Coast Highway north of Santa Barbara—on a section of the freeway now known as US Route 101—entailed a visit to a regional archive of the Department of Transportation of California, CalTrans, located in a nondescript office building on the outskirts of the city of San Luis Obispo. According to the coroner’s report, Murnau’s rented car was traveling north, toward Monterey, late in the afternoon of 10 March 1931.[22] The driver was Eliazar Garcia Stevenson, Murnau’s approximately thirty-one-year-old valet, with John R. Freeland, a twenty-six-year-old chauffeur employed by the car rental company, in the passenger seat. Murnau was sitting on his own in the back. Driving on a stretch of road that was leading uphill in a slight right curve, the car tried to avoid an oncoming truck that was traveling downhill on the wrong side of the narrow, two-lane road. The maneuver failed. The limousine careened to the left, ejected all three passengers, flipped over along the far edge of the road, and came to rest upside down in a filled-in depression between the road and the adjacent train tracks. The valet and chauffeur were injured, but survived; Murnau died the next day in Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara.

The police officers tending to the victims estimated the site of the accident to be approximately a mile away from El Capitan Canyon. Historic blueprints from the early twentieth century in the CalTrans archive record how engineers gradually transformed a meandering coastal pathway into a modern road mostly following the contours of the coast and the profile of the land. Poring over one such map from 1914, an area about one-and-a-half miles out from El Capitan Canyon toward San Francisco stands out. There, the lower end of Cañada del Venadito, or “Canada El Arrastradero Creek” as the 1914 map calls it, crosses under today’s route 101, the southbound lanes of which broadly follow the two-lane road Murnau traveled on. As laid out in 1914 and built in the subsequent decades, the road began there to take its first, gentle curve to the right past El Capitan Canyon while also moving upward. Standing at the side of the road in roughly that spot today, one can still match the coroner’s description of the accident site to the broad lay of the land, including that filled-in canyon between the road and rail track in which the car landed.

Murnau’s final resting place is in Südwestkirchhof Stahnsdorf in the southwest of Berlin. The artist Karl Ludwig Manzel (1858–1936) designed a tripartite, bold travertine wall that bears Murnau’s name; a grave monument far more modern than any of Murnau’s private homes had ever been. Indeed, it is far too modern, even too masculine for the lover of castles, romance, and men who lies buried there. In the center of the wall, Manzel placed a bronze portrait bust of Murnau. From there, the moviemaker’s last gaze goes into the distance, the Ferne where California, Tahiti, and Bali lie.

- I would like to thank Professor Janet Bergstrom at UCLA; Les Hammer; Professor Bruce Robertson, UC Santa Barbara; Steve Vaught; Sian Winship, Society of Architectural Historians/Southern California Chapter; Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin; and Chris Mancini and the Regional CalTrans Archive, CalTrans District 5, San Luis Obispo, for their help with and comments on the text.

- I have followed the English translations of the original German titles given in Lotte H. Eisner, Murnau (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), pp. 273–277. In the case of The Haunted Castle, Eisner does not provide a translation, simply using the original German title—Schloß Vogelöd. In this instance, I have followed the translation offered by Kino International, which released an English-language DVD of the film in 2009.

- This account of Murnau during the war by Wolfgang Schramm is published in Lotte H. Eisner, Murnau, p. 18.

- Ulrike Stoll, Kulturpolitik als Beruf: Dieter Sattler (1906–1968) in München, Rom und Bonn (Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2005), p. 49, n. 53.

- “Eine Künstlerwohnung in Berlin-Grunewald. Das Heim des Regisseurs F. W. Murnau”, Die Dame, no. 20 (July 1927), pp. 8–11.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: Die privaten Fotografien 1926–1931, Berlin, Amerika, Südsee, ed. Guido Altendorf et. al. (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 2013), pp. 60–73.

- Professor Janet Bergstrom kindly alerted me to this identification.

- Tony Villecco, Silent Stars Speak: Interviews with Twelve Cinema Pioneers (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2001), p. 166.

- Tony Villecco, Silent Stars, p. 166.

- 0 David Flaherty, “A Few Reminiscences,” Film Culture, no. 20 (1960), pp. 14–15.

- The word “land” was removed in 1949.

- Steve Vaught kindly shared copies of the building permits for 2863 Durand Drive.

- Guido Altendorf et al., Die privaten Fotografien, pp. 54–55.

- Olive Hatch, “Johnny Weissmuller Heads Aquatic Program at Hollywood Athletic Club,” The Los Angeles Times, 17 May 1928; “Weissmuller Hulvey to Vie with Barfoot,” The Los Angeles Times, 24 May 1928. An earlier visit to Pasadena is recorded for August 1927, but Murnau was still in Berlin at that time.

- Passenger list of the SS Tahiti, departing from Papeete, Tahiti, 24 January 1929, and arriving in San Francisco, 15 February 1929; obtained from “California, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882–1959,” an online database available at ancestry.com.

- Erhard Bahr, Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), p. 289.

- Available at schillerinstitute.org/transl/trans_goethe.html#America. Translation by David Platt.

- Thomas Cole, “Essay on American Scenery,” The American Monthly Magazine, vol. 1, no. 1 (January 1836), p. 12.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, “…der frei im Raum zu bewegende Aufnahmeapparat,” Die Filmwoche, no. 1 (3 January 1924). Quoted in Fred Gehler and Ullrich Kasten, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (Berlin: Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, 1990), p. 141. My translation.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, “The Ideal Picture Needs No Titles: By Its Very Nature the Art of the Screen Should Tell a Complete Story Pictorially,” Theatre Magazine, vol. 47, no. 322 (January 1928), p. 41.

- Ibid.

- Les Hammer kindly shared a copy of the coroner’s report of 17 March 1931, which is filed at the Superior Court of Santa Barbara County. Hammer’s F. W. Murnau for the Record (Morgan Hill, CA: Bookstand Publishing, 2010) offers the most detailed account of the accident and corrects the sordid rumors surrounding Murnau’s death.

Volker M. Welter teaches architectural history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His books include Biopolis: Patrick Geddes and the City of Life (The MIT Press, 2002), Ernst L. Freud, Architect: The Case of the Modern Bourgeois Home (Berghahn, 2011), Walter S. White: Inventions in Mid-Century Architecture (Art, Design, and Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2015), and Tremaine Houses: Private Patronage of Mid-Century Domestic Architecture (forthcoming).