Into the Labyrinth

Designing the carpets that design us

Dan Handel

The year was 2013, and I was sitting in a large atrium hotel in Buffalo, taking a break from the annual meeting of the American Society of Architectural Historians. Aspiring academics trotted alongside senior members of that occult group to catch the panel on the freestanding chapels of medieval Europe or the talk on Lord Chesterfield’s boudoir, but none seemed to be paying attention to the space we were all circulating in.

The hotel was a Hyatt Regency, opened in the mid-1980s as a body double of the better-known examples designed by John Portman Jr. for the chain in the 1960s and 1970s. Apart from the atrium, with its PoMo, turquoise-colored metal structure, the most dominant element in the space was the carpet. Calling it a carpet is perhaps misleading, as it may bring to mind a polite rectangle of a rug, maybe vaguely Eastern in color or Native American in iconography, harmlessly decorating an interior. But no, this was a field of dazzling, oversized oriental flowers, almost obtrusive in its opulence, and as much as I tried, I couldn’t associate the loud pattern and the outrageous color scheme with anything I knew from my art and architectural history education.

The most striking thing about this remarkable surface was how easy it was to ignore. It flooded the entire floor surface so perfectly that it just seemed natural that you would glide on this cornucopia of shapes and textures, which made no attempt to reference the space of the hotel or the urban context around it. There was something else. Spending enough time observing the space made it clear that the carpet works in support of the hotel’s organization, in setting an atmosphere, and in moving people in inexplicable ways. “Why does it look like that?” was therefore followed by “What does it do?” during that long afternoon of carpet watching. As it turned out, there were no simple answers. The historians were not alone in their ignorance: front desk clerks and hotel managers, perfectly capable of guiding you through the thickets of the city’s urban history or recommending the right drink at the bar, had no idea who designed the carpet and with what motives.

Tracking down the performance of carpets in buildings—that is, not only how they appear, but what other functional and psychological aims they may serve—led me far beyond the familiar territories of architecture, to the logic of industrial production and into some of the most profitable and extravagant spaces being designed today.

• • •

Carpets have played a commercial and cultural role since antiquity, when they would circulate widely thanks to the trade empires of the ancient world. Plato is said to have amassed one of the most impressive oriental rug collections in Athens, and the oldest known carpet—the Pazyryk rug, which survived for two millennia by the miracle of perpetual snow—was found in a Scythian grave, testimony of the nomadic people’s cultural links and material exchange with civilizations to the south. Carpets entered the history of art via numerous cameo appearances in the works of Italian and Flemish painters, acting as unassuming table covers that were in reality a status symbol, or placed at the foot of a Madonna, where they would usually indicate the identity and wealth of the patron.[1] During the nineteenth century, several influential scholars made the case for examining more closely the role of carpets in relation to architecture. The careful student of art history might recall Gottfried Semper’s assertion that “the carpet wall plays a most important role in the general history of art,” or Alois Riegl’s influential book Altorientalische Teppiche (Old oriental rugs) from 1891, which brought to the attention of modern designers the patterns and usage of carpets in the East.[2] When Adolf Loos, for instance, designed the interior of the Vogl apartment in Pilsen, the carpets followed certain Eastern traditions and were laid out so as to define areas of circulation and activity. This approach was pretty much followed by modernist architects on those rare instances in which carpets were considered in their work. It is practically impossible to locate a single carpet in the drawings of someone like Mies van der Rohe or Walter Gropius, adamant as they were in advocating the supremacy of exposed surfaces. But in Philip Johnson, for instance, one already finds a recognition that the carpet can delineate areas for specific use, and induce a certain atmosphere. Johnson appreciated the value of good entertainment, and in his Glass House, the carpet—which had been carefully drawn in plan—served as a stage for the socialites and Warhols of the world to perform their routine alongside the shrimp and the hired help. The functional approach, which saw carpets as a programmatic device (this can happen here), remained common for decades and can be found in the works of modernist and contemporary architects alike. However innovative in design or tasteful in position, these carpets are of an entirely different evolutionary branch from the one I witnessed in Buffalo.

• • •

It took me five years to get to the place where the Buffalo carpet was most probably produced. Dalton is a small city in northwest Georgia, home to thirty-something thousand inhabitants and more than 150 carpet and flooring plants. As of 2018, 85 percent of all carpet sold in the US market—which represents nearly 40 percent of global carpet sales—was produced within a sixty-five-mile radius of the city.[3] The sidewalks in Dalton were quiet, but the production facilities were bustling with forklifts and machinery, and branded trucks filled with finished goods were constantly spilling onto the surrounding highways.

The unlikely concentration of production in the city is the result of the regional hand-tufting industry, which had been born, according to local myth, due to the efforts of a single person—Catherine Evans Whitener, a young woman who around the turn of the twentieth century began to revive local candlewicking techniques used to produce tufted bedspreads. These had a distinct, fluffy appearance, achieved by cutting the stitches with scissors and applying hot water in the process. As more women got involved, distributors were attracted to the region, paying the tufters with cash and reselling the bedspreads elsewhere. It was this cottage industry that floated the economy of Dalton throughout the Depression. In the late 1930s, some women took the initiative to repurpose Singer sewing machines for mechanical tufting, which ignited a new industry. New technologies allowed for new products to be created—robes, rugs, and especially carpets, with the latter’s sophisticated, science-based, competitive production facilities gradually taking over the resources of the bedspread business.

But Dalton today is no longer home to a people’s industry reliant on a pool of skilled workers from the region. The city is now the embodiment of a consolidated, multibillion-dollar industry, controlled by a handful of colossal companies that communicate well with the colossal brands that control the properties to be carpeted. These days, its appearance in the news is more frequently related to the pollution of its drinking water, or the fact that snow there sometimes turns blue due to the high concentration of dye particles in the air.

The mills are a good place to learn about this year’s sales and next year’s product lines, but are not very telling with regard to the rationale behind the carpets’ appearance and its performance in space. Managers and workers alike responded with a blank gaze whenever I brought up the word “design,” leading the search further—to the corporate bastions of research and development. Luckily, agglomeration economy demands that these functions be near the production facilities. And so, a few hours’ drive brought me to the magical headquarters of Milliken, one of the companies where color and pattern are conceived, to be later sent into the world: The Roger Milliken Center, a pristine architectural haven in Spartanburg, South Carolina, designed in the late 1950s by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.[4]

The design department is concealed in a modernist box of a building. Behind a low door, one finds members of the select caste of professionals whose unsung influence is visible in the more than ten billion square feet of new carpeting laid down every year.[5] These designers operate according to a completely different value system than the buildings’ architects, often seeing themselves as facilitators in the process of sensing the zeitgeist and feeding it into the machine. The real magic happens within the black box of the proprietary software, which translates human experience into a broadloom color scheme, or into pixels in a digitally printed floor tile. And so landscape watercolors and images of galaxies are turned by the seraphic power of code into fantastic patterns that when produced and poured over floors lend the carpet a marked independence from the architecture of a building. This may sound like the work of technicians, but the adept corporate designer knows how to interweave the visual and psychological impact of her design. These sensibilities would frequently be encoded in the “floodplan,” which is the standard document through which the industry communicates with interior designers and property owners. When executed with a high level of expertise, it can negotiate various viewpoints, capturing both the overarching design concept and the effects to be experienced in space. Looking to find out more about the exact nature of these effects and the perils of independent carpets, I was drawn to the sites of their most extreme articulations.

• • •

Since architectural history could not provide much insight into the carpet landscape phenomenon, it dawned on me that the rationale behind its development lays elsewhere. Most of these dazzling surfaces were to be found in very specific kinds of buildings: hotels, conference centers, and casinos. The floor area to cover was always vast, the number of people passing through significant, the space deep and lacking in orientation.

Historically, the appearance of mega-carpets coincided with the emergence of such spaces in the late 1960s. Never before were so many buildings designed to be such a blend of leisure and work. Never were they so immense and made up of so many interconnected spaces. Never were the carpets so loud and articulated. Technologically, what made these buildings possible were developments such as artificial lighting and air conditioning, which allowed for bigger spaces that operated for longer hours. But what truly gave them form were financial arrangements that sought to encase the American dream of personal freedom and legendary riches in mammoth interiors of sensorial overload designed to increase spending.

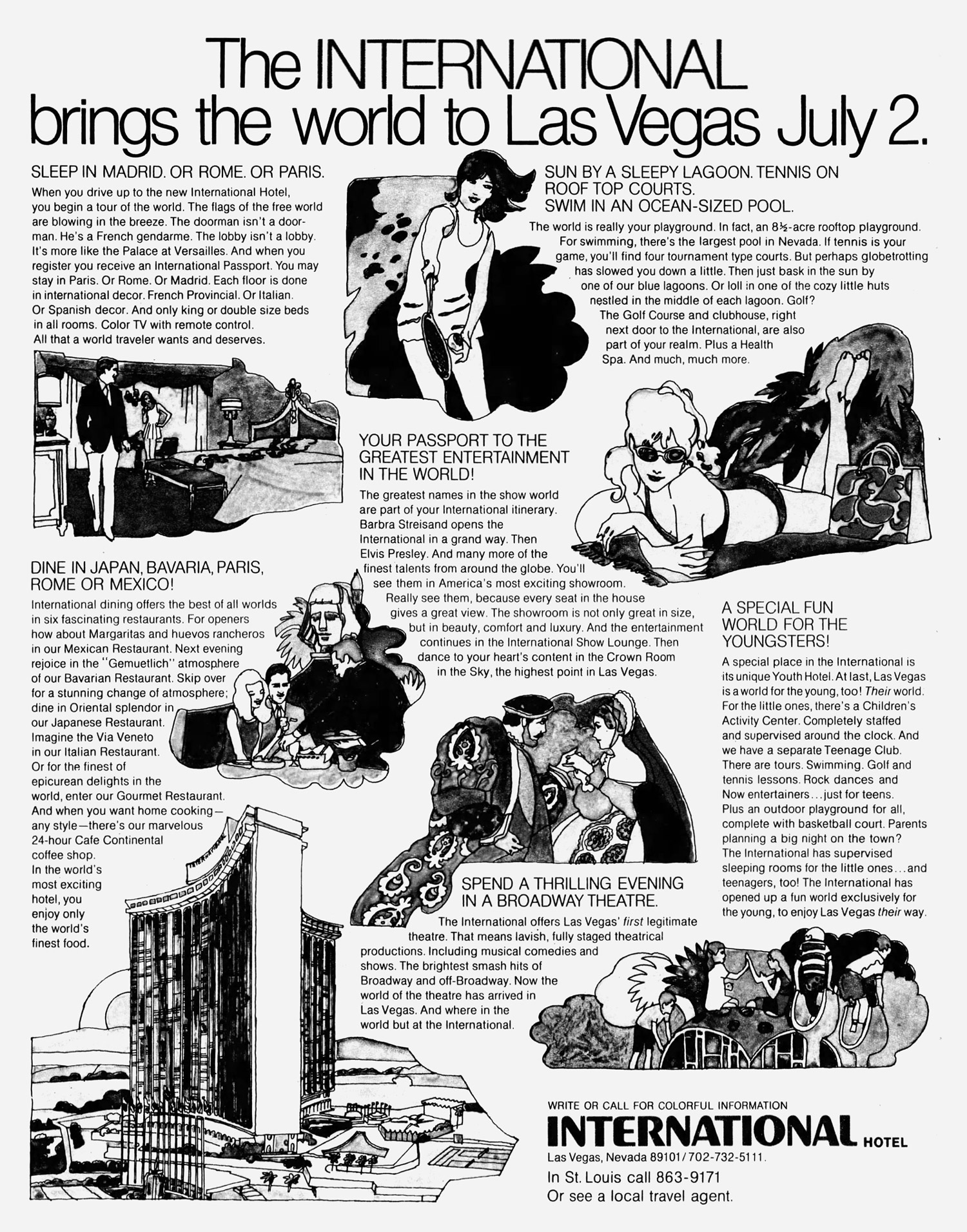

In 1969, Kirk Kerkorian introduced what is considered the first mega-resort in Las Vegas. This was the 1,512-room International Hotel, designed by Martin Stern Jr.[6] In a country fraught with inner city riots, political assassinations, and bloody wars overseas, such a project provided something of a reassurance for the commercial faithful, signaling that not all must be lost to the forces of liberalism and that money could still recreate reality in its image. That was the concept behind the International, where escapism came in the form of all the world’s cultures packed in one complex—where you could have margaritas in the Mexican eatery and then Böfflamott at the Bavarian restaurant; where each floor was decorated to represent another country, and the staff catered to your needs in Scottish kilts or French gendarme uniforms. This interconnected amalgam included, next to the hotel, a restaurant complex, a theater for Broadway shows, a Youth Hotel where staff would babysit the guests’ offspring, a casino for guests to try their luck, and a two-thousand-seat showroom where Elvis Presley performed thirty nights in a row—all to let the outside world know that its services were no longer required.

Groundbreaking as this concept was, it still floundered financially, putting a question mark on the self-mythologizing of Las Vegas as a city built on the visions of eccentric entrepreneurs, from Howard Hughes to Steve Wynn. After Kerkorian failed to raise money to continue operations, he had to sell the International to the Hilton Corporation, which signaled the takeover by professional management of the supposed fantasyland in the desert. With the executives of Hilton came the spirit of the brand, one that required maximum control over every aspect of the property, and as a result, interiors gradually came to be considered components in a total strategy meant to stand out in a saturated market.

In the mid-1970s, the gaming industry saw the creation of a new gospel. Bill Friedman, a recovered gambling addict and casino consultant, began compiling the definitive guide to casino design, including specs for every element in its interior. The resulting book would only be published decades later—under the unapologetic heading Designing Casinos to Dominate the Competition: The Friedman International Standards of Casino Design—but in the meantime, Friedman had made a name for himself as the number one expert on money-making gaming facilities. Nothing was too small to escape Friedman’s obsessive desire to maximize profit: he dedicates paragraphs to the acoustic surfaces reflecting the sounds of gambling and to whatever decorations one encounters in the walk from the car to the casino. In tune with a corporate view of the world, Friedman sees the establishment’s guests as automatons that can be easily manipulated by sensorial stimuli and psychological tactics. Rather than just offering a swingin’ time, Friedman makes sure that the patrons’ weaknesses would be used against them, and he makes it clear that the seduction should start right at the entrance: “Just as the Pied Piper of Hamelin lured all the rats and the children to follow him,” he writes, “a properly designed maze entices adult players.”[7]

The first thing you encounter in the maze is the carpet, and Friedman states that its color and pattern should be carefully chosen: “The carpet is one place brilliant colors can be used. … Reasonably intense colors can amplify players’ excitement as they approach the gambling equipment.” The pattern should be small to conceal stains, and it should be properly padded for players’ comfort during long hours of dedicated gambling. But most importantly, the carpet should be in good taste “because it is the most pervasive decoration in a casino. Its appearance can enhance the atmosphere, or it can create a strong negative impression.”[8]

“Good taste” is, of course, a matter of taste. The era of the Friedmanesque mega-resorts brought with it specimens of carpeting that were unprecedented in their commitment to over-the-top aesthetic experimentation and head-on user confusion. The hard surface flooring and the traditional single-hue carpets one could still find in gambling areas in the 1960s were made extinct by this new generation of delirious surfaces. Covering every inch of the immense floors of gaming establishments, they signaled different use areas, created “yellow brick roads” to carry people from A to B, and played their part in creating the altered state of consciousness understood to be required for maximum spending.[9] By the late 1970s, one can see these patterns looming in the drawings of Martin Stern, who continued to give form to the increasingly complex financial and psychological engineering schemes pushed for by the gaming industry. The architectural mainstream continued to ignore the subject. At best, some were adopting a critical tone imbued with an elitist, Learning from Las Vegas attitude, one that saw academics venturing on brief sorties to these appalling gaming and entertainment universes and then returning with a handful of astute observations—which usually missed the point completely. In the 1980s and 1990s, Las Vegas carpets were adorned with more thematic motifs—from the golden head of Caesar to a coconut tree—and acquired increasing notoriety among intellectuals for how exceptionally ugly and offensive they were to refined taste, even as the populace flocked there in droves.

The resentment masked an ominous feeling among architects, who were coming to the realization that they were no longer in control of their buildings. Except for a few figures (Stern in the gaming sector, John Portman in hospitality), the architecture profession found it hard to follow the accelerating pace of capital and its apathy toward “good” architecture and any predetermined idea regarding the contents of the buildings it commissioned, made especially manifest in the volatile landscape of entertainment and hospitality. How were the students of Bernini and Le Corbusier, trained to believe in the eternal life of built form, supposed to even consider spaces that were predicated on the subjective experiences of their users and measured strictly by the dollar?

In one conversation, a lead designer for the casino industry told me about a case in which a certain dance club, on which millions had already been spent, was dismantled and redesigned as something else entirely due to its failure to comply with the high bar of income per unit area determined by industry experts. Measuring the performance of the space for three months had made it clear that it needed to go. “Luckily,” he said, “they still turned to me to do this, which means that they believe in the power of design to have an impact.” A less sanguine interpretation might contend that such showmanship—necessary for designing in a place like Las Vegas, and to an extent in the entire branded landscape of mega-resorts and ultra-hotels—depends on the ability to recognize that design is, always and under all circumstances, less immortal than money.

Which is not to say that the resulting spaces were always coercive. As the science behind the perfect gaming environment was beginning to explore advanced tracking of behaviors and emotions—as well as sensorial engineering via manipulated air, custom-made soundscapes, and encoded visual cues—there was also emerging opposition to the rat maze paradigm.[10] This new argument claimed that the “zone”—that liminal psychological space in which players, brought to a state of euphoria, are entirely immersed in the gaming activity and are then more prone to take risks—can be achieved and sustained by an entirely different approach to design.[11]

The opposition was led by David Kranes—playwright, English professor at the University of Utah, and casino consultant. In 1991, Kranes ventured on a dérive through several casinos in Las Vegas and published his critical findings in an article titled “Play Grounds.” The text is a piercing architectural critique of casino spaces by an insider attuned both to operators’ intentions and to players’ psychology. “I can walk into any hotel-casino and almost immediately know its survival potential,” he boasts near the beginning, before diving into the details of entrances, thresholds, slot machine and bar placement, and the role of sunlight.[12] Of the Flamingo Hilton, he writes, “The low ceilings and the carpet, both a dark red (no warm colors), close the space in, and one has the impulse to immediately back out through the door and—for survival’s sake—take flight, ” while in the Mirage, he observes, “we are creatures made to feel alive and vital by the sun, and the Mirage has not forgotten this.”[13] As his title suggests, Kranes seeks to advocate a casino design that would feel “pleasurably legible,” that is, one that allows players to understand the space and feel at ease as they slide in from real life into the temporary sphere of play. Kranes draws on Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens, Christopher Alexander’s phenomenological “pattern language,” and Tony Hiss’s “experience of place” to argue for the integration of water and daylight, high ceilings, organic forms, and clear orientation. In short, it was full-on attack on Bill Friedman’s design principles, as well as on the psychological and economic assumptions behind them. And it caught on. After the Mirage, which Kranes cited as a watershed project in the design of Las Vegas casinos, more properties followed the new paradigm, and their profits reportedly skyrocketed.[14]

The gaming industry plays its cards close to its chest, and independent research on casino performance is hard to come by. As part of a milestone, decade-long study by psychologists at the University of Guelph assessing the impact of casino environments’ design on gambling behavior, researchers had to camouflage themselves as handicapped patrons in order to secretly film gaming spaces. The footage was then projected in a 360-degree panoscope that they constructed so that they could simulate different environments and measure participants’ emotional responses. Their conclusion was that respondents were likely to spend more time in, and more likely to return to, a playground environment.[15] Kranes puts it more bluntly: “In the Friedman model, casinos act like drug dealers—abusing and ‘hooking’ the ‘users.’ Their lure is that of a one-night stand … [but] a buyer’s market requires the casino to try to secure the gamer as a return customer.”[16]

So jagged carpet patterns are out of fashion, and the ugly carpets some of us abhor may be on the decline. Kranes is hopeful that more and more establishments will use their carpeting to guide their customers on a pleasant, wallet-draining journey rather than disorienting them between walls of one-armed bandits. This approach, resting as it does on psychological observations, also anticipates a more accurate measuring of affect. As behaviorist and neuroscientific methods are increasingly applied in the gaming industry in order to optimize the financial performance of spaces, the potential of carpets to influence patrons in pervasive ways may be mobilized through ever more sophisticated designs.

• • •

Spending time with Kranes’s playground ideas made me think that I may have missed a piece of the puzzle, one that turned out to have been hiding in plain sight in the history of architecture. In the 1960s, several artists and architects floated the idea of the “megastructure.” These immense buildings, it was argued, could offer relief from the monotony and anonymity of industrial civilization, and give outlet to people’s creative impulses, thus forming a more perfect future society. One of the major proponents of this idea, Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys, relied on the anticipated coming of Homo ludens when creating maze-like complexes the size of cities, which came complete with color, sound, and tactile elements designed to invoke sensorial stimuli.

Walking through yet another casino floor, I began to wonder whether Constant’s New Babylon had been reincarnated in the Luxor: the expansive scale of the interior, the deliberate bombardment of the senses, and the almost tangible presence of the dark sides of human behavior were all in place. As was the aura of ephemerality, of both architecture and experience. The oversized oriental flowers on the carpet leading me through clouds of cigarette smoke and clouded facial expressions were rhyming with the ones seen in Buffalo. The space became nothing more than an echo of a bygone dream of individual emancipation, now used to lure in voluntary prisoners for maximized profit. All that is solid melts into perfumed air.

I wish to thank Assaf Evron for his insights, which gave this project structure and visual form; David Kranes for the invaluable leads; the Graham Foundation for supporting the research; and the Canadian Centre for Architecture, which challenged me to turn it into an exhibition.

- In writing about the carpets that frequently appear in the works of painter Lorenzo Lotto, David Young Kim writes: “Scholarship … has generally treated his paintings as invaluable documents that establish the date and appearance of certain carpet types. … [However,] Lotto meditated on the material constitution of the carpet as a woven product to convey his particular approach to the medium of painting as well as to underscore his authorship.” See Kim, “Lotto’s Carpets: Materiality, Textiles, and Composition in Renaissance Painting,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 98, no. 2 (June 2016), p. 181.

- Gottfried Semper, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave and Wolfgang Herrmann (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 103. The term “carpet wall” refers to a wall made of woven textiles, such as in a nomadic tent.

- The Carpet and Rug Institute, “Quick Facts about the Carpet Industry.” Available at carpet-rug.org/resources/research-and-resources.

- Milliken is one of the more innovative producers in the flooring industry. Their US patents run into the thousands, including the first digital carpet printer in the industry.

- That area is equivalent to almost sixteen Manhattans. The figure for 2019 carpet sales is cited from “Scoring Flooring: Industry Stats for 2019,” Floor Covering News, 30 June 2020. Available at fcnews.net/2020/06/scoring-flooring-industry-stats-for-2019.

- Stern Jr. was probably the most prolific casino hotel architect in the US, designing—besides the International—the original MGM Grand (1973), the unrealized-yet-groundbreaking Xanadu (1975), and additions to the Sands, the Sahara, and the Riviera.

- Bill Friedman, Designing Casinos to Dominate the Competition: The Friedman International Standards of Casino Design (Reno, NV: Institute for the Study of Gambling and Commercial Gaming, 2000), p. 64.

- Ibid., p. 139.

- In her book on casino design and addiction, cultural anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll describes cases in which gamblers were so absorbed in play that they were completely “unaware of their immediate surroundings, each other, and even a dying man at their feet.” See Schüll, Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), p. 35.

- A lead designer I spoke to dispelled the myth of oxygen being pumped into casino spaces, but admitted that the air is engineered to resemble outside air. The perfect formula, he argued, consists of filtering and circulation systems that increase air movement in ways that emulate a light breeze, and just a hint of citron.

- The idea of being “in the zone” evolved in the mid-1970s out of positive psychology, in which it is referred to as “flow state.”

- David Kranes, “Play Grounds,” Journal of Gambling Studies, vol. 11, no. 1 (Spring 1995), p. 93.

- Ibid., pp. 97, 99.

- Developer Steve Wynn’s Mirage was planned by architect Joel Bergman, a former Martin Stern Jr. employee; the interiors were designed by Henry Conversano and Roger Thomas.

- The research evolved over almost a decade and ended abruptly after the passing of the lead researcher, Karen Finlay. For examples of their work, see Karen Finlay, Vinay Kanetkar, Jane Londerville, and Harvey H. C. Marmurek, “The Physical and Psychological Measurement of Gambling Environments: Final Report to OPGRC” (2004), and “Casino Décor Effects on Gambling Emotions and Intentions,” Environment and Behavior, vol. 42, no. 4 (July 2010). The two papers are available at greo.ca/Modules/EvidenceCentre/files/Finlay%20et%20al(2004)The_physical_and_psychological_measurement_of_gambling_environments.pdf and researchgate.net/publication/249624622_Casino_Decor_Effects_on_Gambling_Emotions_and_Inten, respectively.

- David Kranes, email to the author, 17 December 2019.

Dan Handel is a writer and curator based in Haifa. He works on research-based projects, with special attention to underexplored ideas and practices that shape contemporary built environments. In 2021, he curated the exhibition “The Design of Carpets that Design Us” at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal.