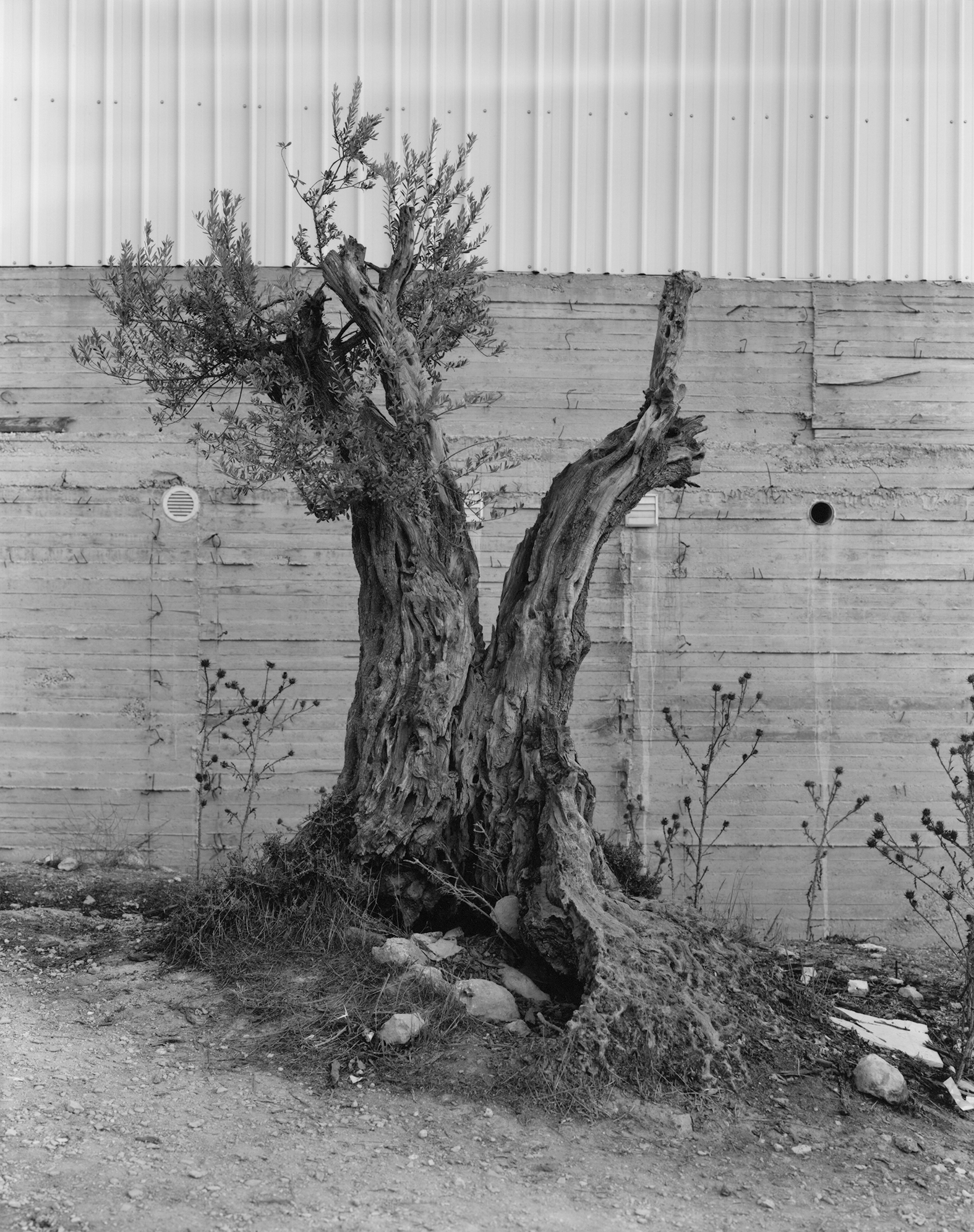

Artist Project / Anchor and Archive

The uprooting of Palestinian olive trees

Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez

Irus Braverman introduces an artist project by Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez, which records the appearance and coordinates of sixty olive trees in the West Bank.

Two major arboreal landscapes prevail along the mountainous strip that cuts across the center of Palestine-Israel from the Hebron hills in the south to the Galilee in the north: conifer pine forests and deciduous olive groves. These treescapes are neither as random nor as natural as they might first seem. Trees in general, and olive and pine trees in particular, play a pivotal role in both Palestinian and Jewish lives and narratives in this region.

Since 1901, the Jewish National Fund, an organization established by the Fifth Zionist Congress to purchase land for Jewish people in Palestine, has planted more than two hundred and fifty million trees in the region, mostly pines. Over the years, the pine has become an emblem of the Zionist project of afforesting the Holy Land and turning it into a European landscape. While this tree has been central to “making the desert bloom,” as the Zionist phrase goes, so too has the olive tree become emblematic of the Palestinians’ steadfast connection (sumud) to the land. In assuming the totemic qualities of their people, both olive and pine trees signify and amplify colonial structures and dynamics.

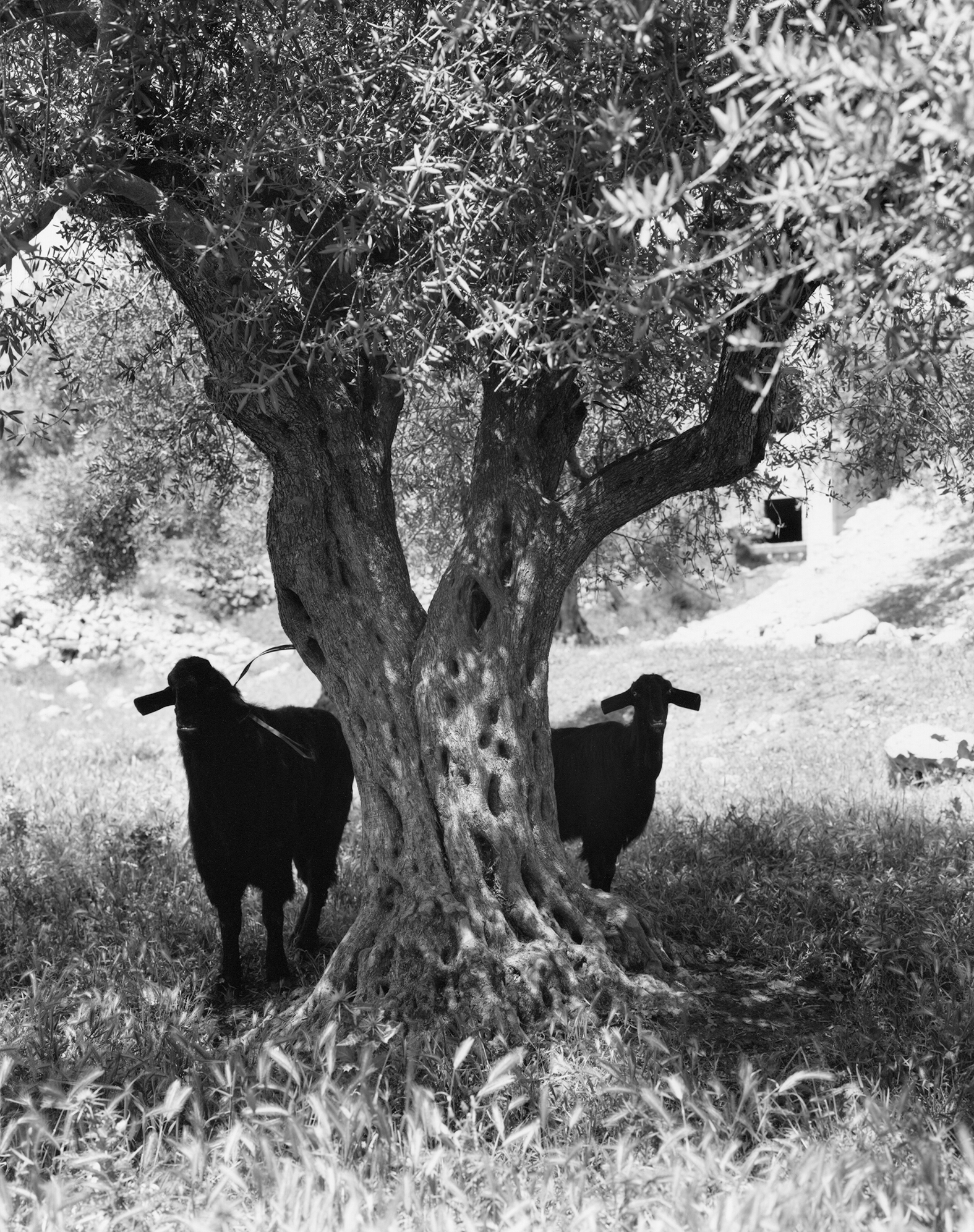

With an estimated total of ten million trees, olives are the largest single agricultural product in the occupied West Bank.[1] Roughly one hundred thousand Palestinian families rely directly on the olive harvest for their livelihood. With another fifty thousand people working with olive trees and their produce, between a quarter and a third of the Palestinian population of the West Bank depends on them.[2] During the harvest in October and November each year, the olive groves become places of celebration where families and friends gather to partake in traditions that have been practiced for generations.

Precisely for this strong physical, cultural, symbolic, and economic relationship with the Palestinians, olive trees have become targets for violence by the state of Israel and by Israeli settlers. A study published in 2012 by the Applied Research Institute Jerusalem estimated that since 1967 Israeli authorities have uprooted eight hundred thousand Palestinian olive trees in the West Bank.[3] Of 211 reported incidents of trees being cut down, set ablaze, stolen, or otherwise vandalized in the West Bank between 2005 and 2013, only 4 resulted in police indictments.[4]

There are multiple rationales behind uprooting trees. As punitive measures, such practices predate the state of Israel. Ottoman rulers uprooted the olive trees of local farmers (fellahin) as punishment for tax avoidance, and the British administration in Palestine later carried out uprootings through emergency regulations. However, Israel’s central rationale for uprooting olive trees has not been presented as punitive, or at least not explicitly so: the Israeli army has uprooted and continues to uproot thousands of olive and other fruit trees for the construction and maintenance of the Separation Wall and to secure roads, increase visibility, and make way for watchtowers, checkpoints, and security fences around settlements in the West Bank.

Additionally, the olive has been uprooted under the aegis of protecting the region’s wild plants. Israel often portrays Palestinians as innately antienvironmental, justifying its intervention as being on nature’s behalf. In a criminal court case against a Palestinian farmer who planted olive trees on his private land in the occupied West Bank, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority claimed that planting new “non-wild” olive trees in nature reserves is harmful from an ecological standpoint. Israel’s chief ecologist in “Judea and Samaria” argued before the court that the trees “might damage fauna and flora” because of the machinery, ploughing, and irrigation involved in their planting.[5] Based on this logic, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority has uprooted thousands of olive trees in its parks and reserves, especially in the West Bank.

Despite the biblical prohibition of uprooting fruit trees—even an enemy’s trees during war—the uprooting of Palestinian olive trees proceeds with immense fervor. According to the United Nations, more than seventeen hundred olive trees were vandalized during the 2020 olive harvest alone.[6] The olive might thus be understood as an “enemy soldier”: a totemic displacement of the adversary itself. For the Israeli state, these enemy soldiers are a threat to its existence and must therefore be eliminated from the landscape. The powerful affinity between the Palestinian people and the olive tree is thus not only the result of its economic, cultural, and historical significance, but increasingly also a product of its brutal targeting by the state of Israel and by certain Israeli settlers.

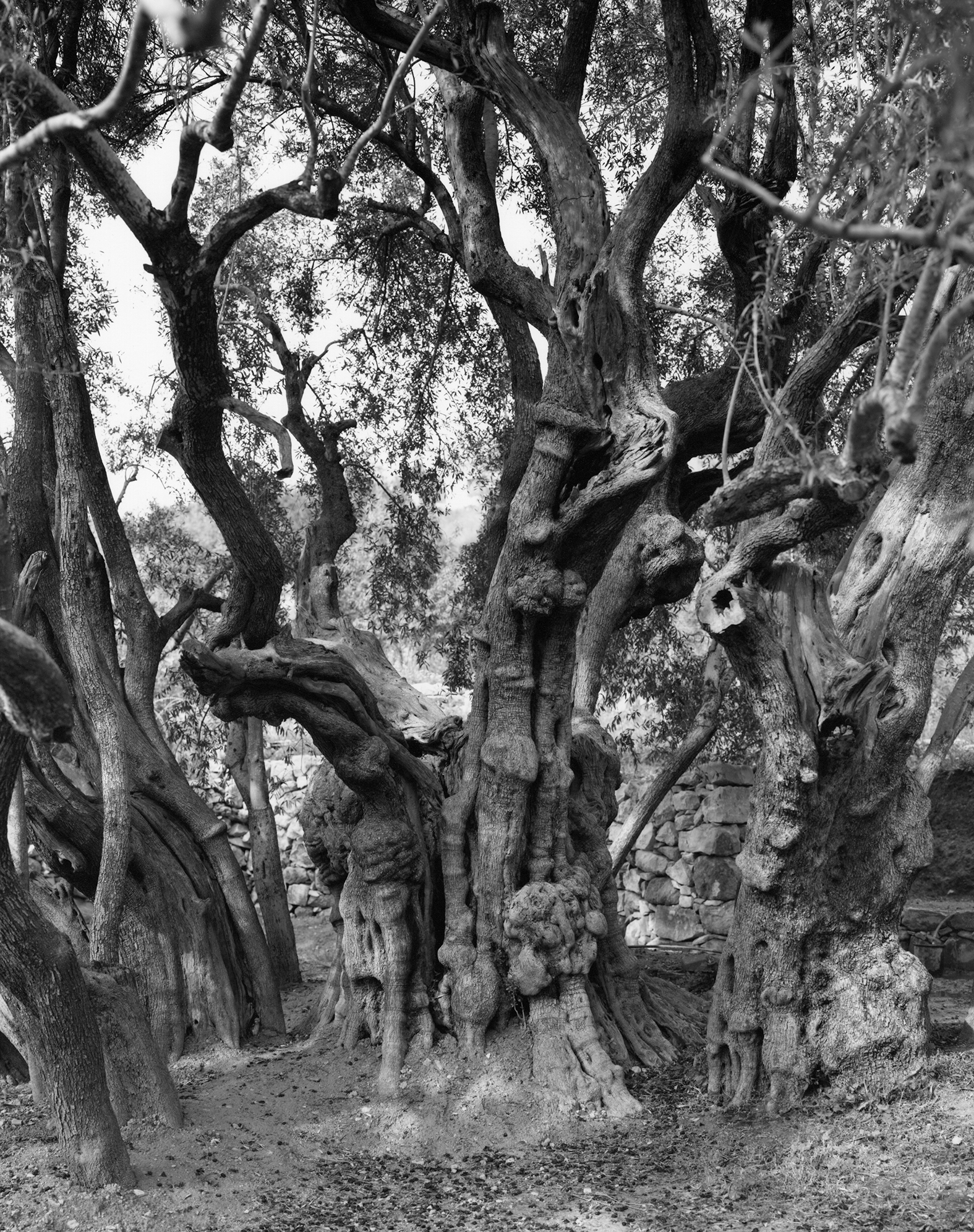

Through burning, uprooting, and denying Palestinians access to olive trees, the state of Israel and Israeli settlers have vested the tree with enormous power. The olive’s steadfastness, durability, and extraordinary longevity are all acutely representative of the Palestinian struggle against Israel’s settler colonialism and its occupying regime. The olive acts as both an anchor and an archive, standing for the Palestinians by witnessing and testifying to what is no longer there. Planting and cultivating olives becomes a project of Palestinian resistance.

There has been an international outcry over the uprooting and burning of Palestinian olive trees, and Palestinian farmers have been embraced by human rights organizations in Israel and worldwide, yet the sabotage of olive trees remains an everyday occurrence. The 2023 Israeli offensive on Gaza following the Hamas attacks of October 7 has introduced record-breaking levels of state-backed settler violence in the West Bank. While international attention has been focused on Gaza, settlers—emboldened with new weapons and enhanced legitimacy—turned the 2023 olive harvest into a life-threatening event. On October 28, Bilal Mohammad Saleh was allegedly shot in the chest by a Jewish settler while picking olives on his family’s land in the northern West Bank. His body was carried out to the road on the ladder that he had been using to reach his olives, witnesses reported.[7] Last year, many Palestinian villagers across the West Bank were unable to access their olive trees, suffering immense losses as a result.

Such actions by Israel have recently been augmented by another form of takeover: this time through configuring the olive tree as the new Zionist tree. Indeed, in 2021 the Jewish National Fund elected the olive as Israel’s national tree in a ceremony marking the 120th anniversary of this organization, whose disastrous legacies of pine afforestation still linger in the natural landscape. During the event, the Jewish National Fund’s chairman stated that “the olive tree is mentioned many times in the Bible, it is one of the seven species in which the Land of Israel was praised and above all the olive has become a symbol of peace.”

Strongly rooted in the Jewish tradition, such visions of peace are difficult to imagine amid the unprecedented violence currently taking place in Palestine-Israel. “We haven’t been to the trees since Bilal was shot,” one Palestinian villager lamented in November 2023. “You have to understand: olive trees take a long time to grow. Maybe 50 years or more, so you can’t just replace them. For me, my olive trees and my sons are the same. They are all my children.”[8]

Irus Braverman, Settling Nature: The Conservation Regime in Palestine-Israel (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2023).

Irus Braverman, “Uprooting Identities: The Regulation of Olive Trees in the Occupied West Bank,” PoLAR, vol. 32, no. 2 (November 2009).

Irus Braverman, “‘The Tree Is the Enemy Soldier’: A Sociolegal Making of War Landscapes in the Occupied West Bank,” Law & Society Review, vol. 42, no. 3 (September 2008).

Images and text reproduced from Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez, Anchor in the Landscape (Mack, 2024).

- United Nations “The Olive Harvest in the West Bank and Gaza,” October 2008. Available at unispal.un.org/pdfs/olive_harvest_fs08.pdf.

- Jason Burke and Sufian Taha, “’No Work and No Olives’: Harvest Rots as West Bank Farmers Cut off from Trees,” The Guardian, 30 November 2023. Available at theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/30/no-work-and-no-olives-harvest-rots-as-west-bank-farmers-cut-off-from-trees.

- Mel Frykberg, “Environmental Terrorism Cripples Palestinian Farmers,” Relief Web, 6 April 2015. Available at reliefweb.int/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/environmental-terrorism-cripples-palestinian-farmers.

- Yesh Din, “October 2013 Data Sheet on Vandalism of Olive Trees,” 21 October 2013. Available at yesh-din.org/en/october-2013-shouldnt-it-be-2014-data-sheet-on-vandalism-of-olive-trees-law-enforcement-on-israeli-citizens-who-vandalize-palestinian-owned-olive-trees-in-the-west-bank-2005-2013-3.

- Irus Braverman, Settling Nature: The Conservation Regime in Palestine-Israel (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2023), pp. 152–153.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “2020 Olive Harvest Season: Low Yield amidst Access Restrictions and Settler Violence,” 13 January 2021. Available at ochaopt.org/content/2020-olive-harvest-season-low-yield-amidst-access-restrictions-and-settler-violence.

- Hana Elias, “For Palestinians in the West Bank, This Olive Harvest Is Literally Life-Threatening,” The Nation, 15 November 2023. Available at thenation.com/article/society/settler-attacks-threaten-palestinian-olive-harvest

- Jason Burke and Sufian Taha, “No Work and No Olives.’”

Adam Broomberg is an artist, activist, and educator. His work was included in “South West Bank,” an exhibition on display at the 60th Venice Biennial. His activist work includes founding Artists + Allies x Hebron, a non-governmental organization that he co-directs with the celebrated Palestinian human rights defender Issa Amro. For two decades, he was one half of the critically acclaimed artist duo Broomberg & Chanarin. Together, they had numerous solo exhibitions, including at the Centre Pompidou (2018) and the Hasselblad Center (2017).

Rafael Gonzalez is a lens-based artist

and educator living in Berlin. He is an alumnus of the

one-year program at the International Center of Photography in New York and is a founding board member of

the Berlin-based non-governmental organization Artists + Allies x Hebron. He currently teaches at the SRH Berlin School of Design and Communication.

Irus Braverman is professor of law, adjunct professor of geography, and research professor at the Department of Research and Sustainability at the University at Buffalo, the State University of New York. Her main interests lie in the interdisciplinary study of law, geography, and anthropology.