Better Luck Next Time

Small consolations

Gregory Williams

There’s nothing like the knowledge of one’s pending execution to inspire a need for comfort. As the 6th-century philosopher Boethius sat out his last days in a dungeon near Rome, accused by King Theodoric of high treason, he penned his Consolation of Philosophy, an imaginary discussion between the condemned man and Lady Philosophy. The ensuing debate pits the all-too-human sense of self-pity against the saving grace of rational thought, the only means of preventing a lapse into pointless sentimentality. As a Christian, Boethius did seek spiritual solace, but only insofar as it was reinforced by the practice of a clear-headed, rigorous assessment of his circumstances. A similar situation confronted Sir Thomas More, who wrote his Dialogue of Comfort in the Tower of London while Henry VIII and his cronies deliberated over More’s demise, which happened in 1535 when he was beheaded. Like Boethius, he invented a conversation, this one between two Hungarian relatives (stand-ins for the threatened English Catholics) trying to come to terms with their likely deaths at the hands of the Turks. For More as for Boethius, a period of anxious anticipation and fear is made tolerable by the soothing words of an internal dialogue.

The terms consolation, comfort, and condolence are often used interchangeably in such contexts, motivated, of course, by the presence of death. Letters of condolence in particular have a long history, with records going back to the ancient Greeks. While on a trip in 90 AD, Plutarch famously consoled his wife upon learning of the death of their two-year-old child. He praises her dignified response to the tragedy: “It did not surprise me that you, who have never tricked yourself out for theaters or processions and have always believed that expense was useless in pleasures, should also have maintained the same simplicity and modesty in time of sorrow.”[1] Stoic acceptance of grief was certainly not the only option for the mourning relative, but it offered a measure of dignity and acknowledged the fleeting nature of life with quiet resolve.

A more recent phenomenon in the category of loss management is the consolation prize, often associated with casualties suffered in the sports arena. In the classical Greek games, prizes were awarded only to the single victors, who typically received the modest gift of an olive branch. They were also given all manner of material rewards by the cities they represented, but the original goal was to establish everlasting fame on earth, the sure route to immortality. Defeat in the classical era was linked with a failure to live on in legend. Only with the rise of the modern Olympics, first held in Athens in 1896, did the practice of granting medals to second- and third-place finishers become established. Yet despite the modern effort to make all talented participants feel recognized as winners, there is still the sense that only absolute triumph will do. Perhaps the most indelible memory taken from Olympic games is the expressions of bitterness on the faces of the silver and bronze medalists. Though they have clearly accomplished a remarkable task, there can be nothing more depressing to an athlete than to hear a sports commentator say, “She gave it an excellent try, but it just wasn’t her night to take the gold!”

Indeed, constant advances in camera technology have enabled television coverage of Olympic events to become increasingly invasive. The number of angles from which an athlete’s every facial expression and bodily contortion is recorded has raised spectator voyeurism to an uncomfortable level. When Sarah Hughes upset the pool of favorites in women’s figure skating at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, viewers were able to closely observe the corners of Michelle Kwan’s mouth for signs of twitching as she grudgingly accepted the bronze medal. Even well after the award ceremonies had ended, the network revisited the negative aspect of “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat” (the classic motto of ABC’s Wide World of Sports) in such relentless fashion that any sense of sympathy with the competitors was lost. The whole experience gradually took on the air of a vast and highly public wallowing in Schadenfreude.

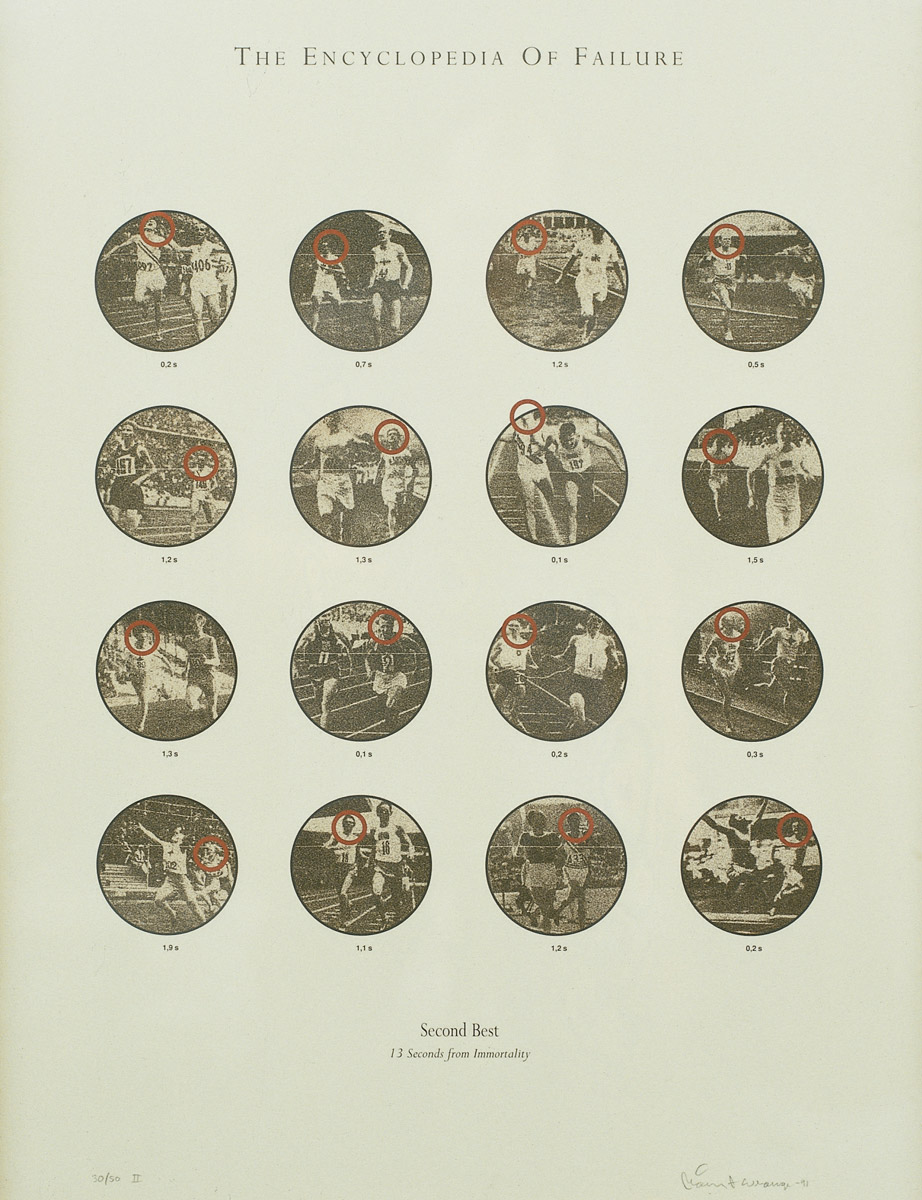

The artists Måns Wrange and Tracey Moffatt take two different views of Olympic-scale downfall in their manipulation of photographic documentation. Wrange concentrates on the moment before the official results are announced, just when the top two finishers from historic competitions pass through the ribbon. He highlights the instant of the photo-finish as the runner-up first becomes aware of the fact that it is all over. Out of the sixteen images from this section of Wrange’s Encyclopedia of Failure, a mere thirteen seconds collectively separates all victors from the vanquished; “13 seconds from immortality” must feel like an eternity. Each of these temporal fragments brings to mind Roland Barthes’s equation of photography and death. The click of the shutter is a form of indirect violence, leaving the second-place runner with a lifetime’s worth of proof that victory is forever irretrievable.

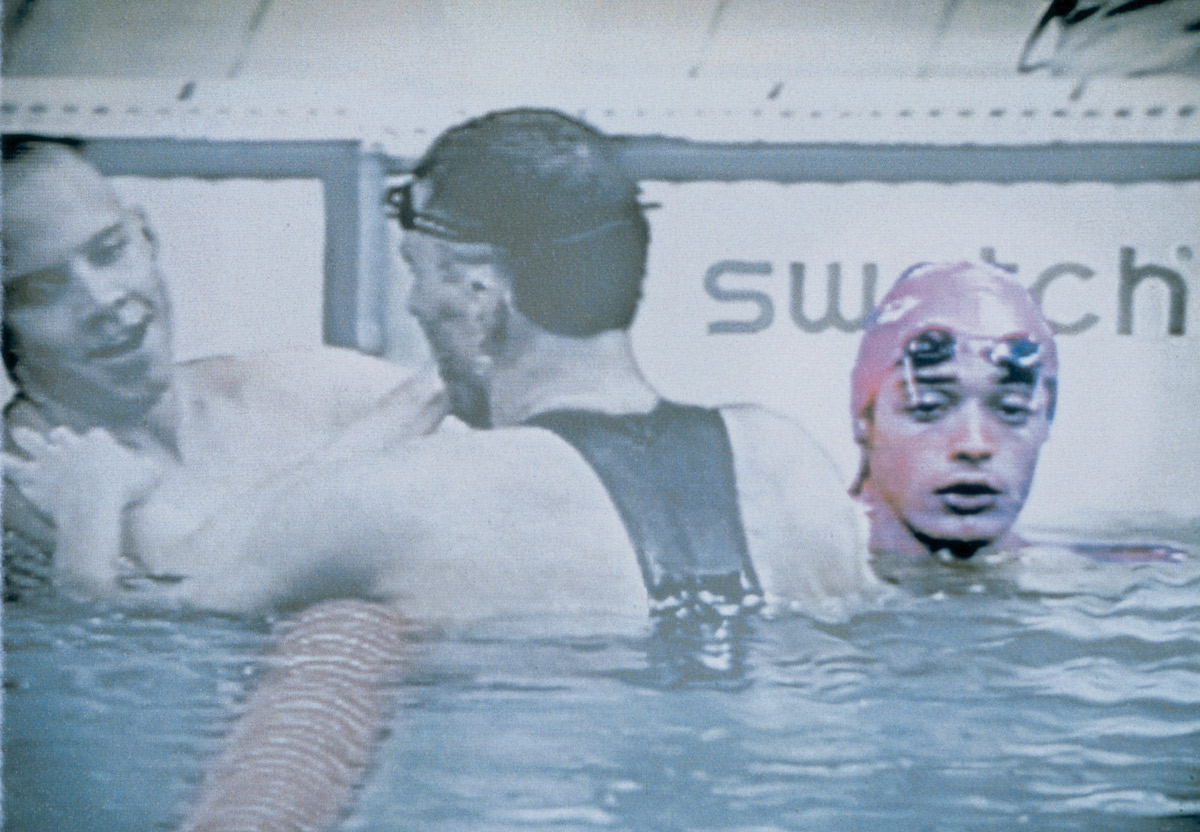

Moffatt, on the other hand, considers fourth place to be the ultimate form of disappointment. To get so close to a medal but to come up short can only be devastating. Like Wrange, she focuses on that decisive shudder of recognition as it is registered on the faces of athletes who will not be ascending the platform to receive even a conciliatory ribbon. As Moffatt stated in a press release for her “Fourths” series (2001), “Fourth means that you are almost good. Not the worst (which has its own perverted glamour) but almost a star.” Her project refers us back to the ancient Olympic desire for fama, that sure route to everlasting glory. Moffatt enacts a futile rescue operation in order to grant the non-medalists a brief reprieve from their historical obscurity. The effect, however, is to forcefully call attention to their misery, plainly visible on their highlighted faces.

- Sarah B. Pomeroy, ed., Plutarch’s Advice to the Bride and Groom and A Consolation to His Wife (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 60.

Gregory Williams is a critic and art historian living in New York City. He is also an editor of Cabinet.