The Doll Games

Thirty years on, a scholarly reconsideration of the Jacksons’ childhood world

Pamela Jackson and Shelley Jackson

This excerpt from the Jacksons’ unfinished collaboration is edited and introduced by J. F. Bellwether, Ph.D.

The Doll Games are a ground-breaking series of collaborative improvisations by Shelley and Pamela Jackson that took place in a private home in Berkeley, California, in the first half of the 1970s.

The Doll Games cannot be precisely dated. 1970 and 1976 are generally understood to mark the limits of the period of greatest energy and invention, though any attempts to identify an inaugural moment are defeated by the nebulous nature of the phenomena under discussion. The Doll Games did not spring fully formed out of a Mattel box, but evolved by degrees out of earlier games (stuffed animals, “Kleenex dolls,” Kiddles). When did the Doll Games begin? As Babette Jackson has said, “That depends on how you define the Doll Games.” The ending point of the Doll Games is easier to locate, though too much weight has been placed on Shelley Jackson’s famous dictum (1976): “People are more interesting than dolls.”[1]

The Games themselves, as well as the numerous documents and artifacts they generated, borrowed freely from literary and consumer culture. To make up a cast of characters comprised of swashbuckling heroines, tender heroes, bumbling he-men, whores and roués, the Jacksons used whatever material came to hand with bold directorial instincts and a sense of identity fluid in the extreme. Barbie’s kid sister Skipper got a butch haircut and later, clay breasts, and became the dashing heroine Aina; baby dolls were reimagined as obese adults; Little Red Riding Hood, sporting a moustache, became the lecherous wolf Harvey, the Doll Games’ enduring antihero.

Similarly, the Games’ highly conventionalized narratives, employing stock scenarios such as “pirates,” “the orphanage,” “the rebel princess,” and “running away,” appropriated and remixed elements of the epic, comedy, romance, and farce. (Tragedy and gothic horror, though deliberately excluded from the doll world, visited the Doll Games from without, a point I make in “Laurie Reborn: Death, Resurrection, and the Chaste Hermaphrodite in the Doll Games of Shelley and Pamela Jackson.”[2]) Giving the postmodern pastiche a comradely nod but eschewing its cynicism, the Doll Games have confused some critics. Never afraid of acknowledging wish-fulfillment as narrative’s primum mobile, the Doll Games presented a resolutely cheerful Weltanschauung, leading some scholars to dismiss them as naïve. However, this scholar would argue that this optimism was a radical gesture, given that the values the narratives affirmed were in stark contrast certainly to playground norms, but also to those of the larger society around them—a contrast of which the artists were very much aware.

The Doll Games emerged in Berkeley, California, at a time when gender, politics, race, and sexuality were fiercely and publicly debated. Indeed, as the dolls were taking their first steps toward literary history, the artists’ family was opening a feminist bookstore just down the street from People’s Park. The Doll Games’ privately staged confrontations between androgynes and “dainty ladies,” their outlaw utopias and anarchic child societies, and their uncompromising moral vision, cannot be understood without reference to the larger public discourse in which they took place.

The Doll Games held up a funhouse mirror to their times, and what survives of them are historical documents of a wobbly, comical sort. But the Doll Games transcend their epoch. Intricate, obsessional, moral, violent and sexual, funny and tragic, the Doll Games propose doll games as a true folk art form, renewing itself with every performance. Obedient to no rules except those its practitioners invented for themselves, completely collaborative, the Doll Games was a genuinely interactive art form. In this theater of two, every audience member was a co-creator.

“The Doll Games” is also the title of a project the adult Jacksons undertook to document their childhood collaborations. It was conceived at different times as, variously, a multimedia art extravaganza, a work of postmodern cultural criticism, an open-to-the-public celebration of and clearing house for foul-mouthed ex-little girls, and a collection of thoughtful and rather poetic autobiographical essays. It is no wonder that it became none of these things, but languished as a collection of poorly copyedited fragments in the files of the Jacksons, while they went on with less ambiguous projects—until I, as a tenacious admirer and scholar of the original Doll Games, persuaded them to abandon their files to the ministrations of my jiggling keyboard. As an independent scholar I have studied the Doll Games for some years; I feel immensely privileged to introduce this curious little world to a new audience.

It is up to the reader to say whether a Doll Games configured and, yes, perhaps disfigured by an epigone can succeed where, by their own admission, the adult Jacksons’ own “Doll Games” failed. That abandoned project has been for some years a ruined edifice housing a ruined edifice: a mystery inside an enigma. It has haunted me. This fossil, this derelict, I have done my best to disensepulcher, and even, in so far as it is possible for one not privy to the secrets of the Doll Games first hand, to restore. I consider myself in the light of an archaeologist working two sites at once: a ruined city, and the ruined city it was built upon. Perhaps this work of mine will itself fall to ruins and become the object of a future archaeologist’s course of study, and perhaps the opus that results from that study will fall to ruins in turn and await a still more future scholar of endeavors past, and so on. Or perhaps in my own investigations I will penetrate so far into these worlds within worlds that I will find myself examining the back of my own head, having come full circle.

Not the least peculiar object that has come down to us from that late, decadent period of the Doll Games so particularly rich in artifactual droppings, is a doll-sized mirror. A crude moustache, eyebrows, and shaggy “do” have been cut from electrical tape and arranged on the face of the mirror in such a way that a doll (or her handler) sees her face transformed. This influencing machine, fashioned with who can say what degree of knowingness about the theatricality of gender, this all-purpose Duchamp, is already tremulous with the implied moustache of Harvey, but—mise en abyme—when Harvey himself is the Narcissus, becomes delirious with the double spectacle/specularization of the moustache-implicit antagonizing and defeating the moustache-explicit. Which latter, to add exquisite layers of irony, is itself a disguise and a supplement, so that the transfigured Harvey in the mirror might look to him/herself, if you will pardon this fancy that bestows sight on a doll, rather more feminine than usual, in his/her reduplicated facial decorations, because more like any other female in a false moustache, and therefore both less like him/herself (“Harvey”) and more like him/herself at once, restored to the Little Red Riding Hood that is hidden inside every wolf.

As, in my mind’s eye, I look at a little girl looking at a doll looking at a reflection of a doll disguised—and unveiled—in the candid duplicity of this most extraordinary mirror, I may be excused, I hope, for experiencing a moment of vertigo, especially if I inform the reader that I too have a moustache, and for a moment seem to glimpse my own image in the glass. Is it possible that I am neither the critic nor the audience, but just the latest dummy of the Jackson girls—that those pint-sized ventriloquists are throwing their voices out of the past, not to reveal their secrets, but to play yet another Doll Game?

—J. F. Bellwether, Ph.D.

Presented to S. Jackson under the name “Fluff” in Christmas of 1970 or 1971, Aina became the Doll Games’ first and finest heroine. A cheeky tomboy with cropped hair and a wide smile, Aina led the games through most of their finest years together with Laurie, her sidekick and romantic partner, playing such roles as runaway princess, orphan girl, and pirate apprentice with pluck and panache. Aina acquired a second head some years after the first, and alternated between the two thereafter. She was supplanted by identical twins Mara and Melanie in the later Doll Games; this is generally considered to mark the beginning of the decadent era, and of the Doll Games’ eventual decline.

The Doll Games’ most beloved boy hero and its martyred saint, born into the Barbie family as little sister “Skipper,” passing into the hands of P. Jackson on Christmas of 1970 or 1971, and recast soon thereafter as Laurie, androgynous twin and chaste lover of Aina. Sensitive, lithe, comely, with flowing hair, Twist ‘N’ Turn body, and poseable wrists, Laurie embodied the Doll Games’ romantic male ideal. Tragically mutilated during a makeover, the circumstances of which remain shrouded in mystery, his body, and perhaps some part of his spirit, lived on in his sometime rival, Jesse.

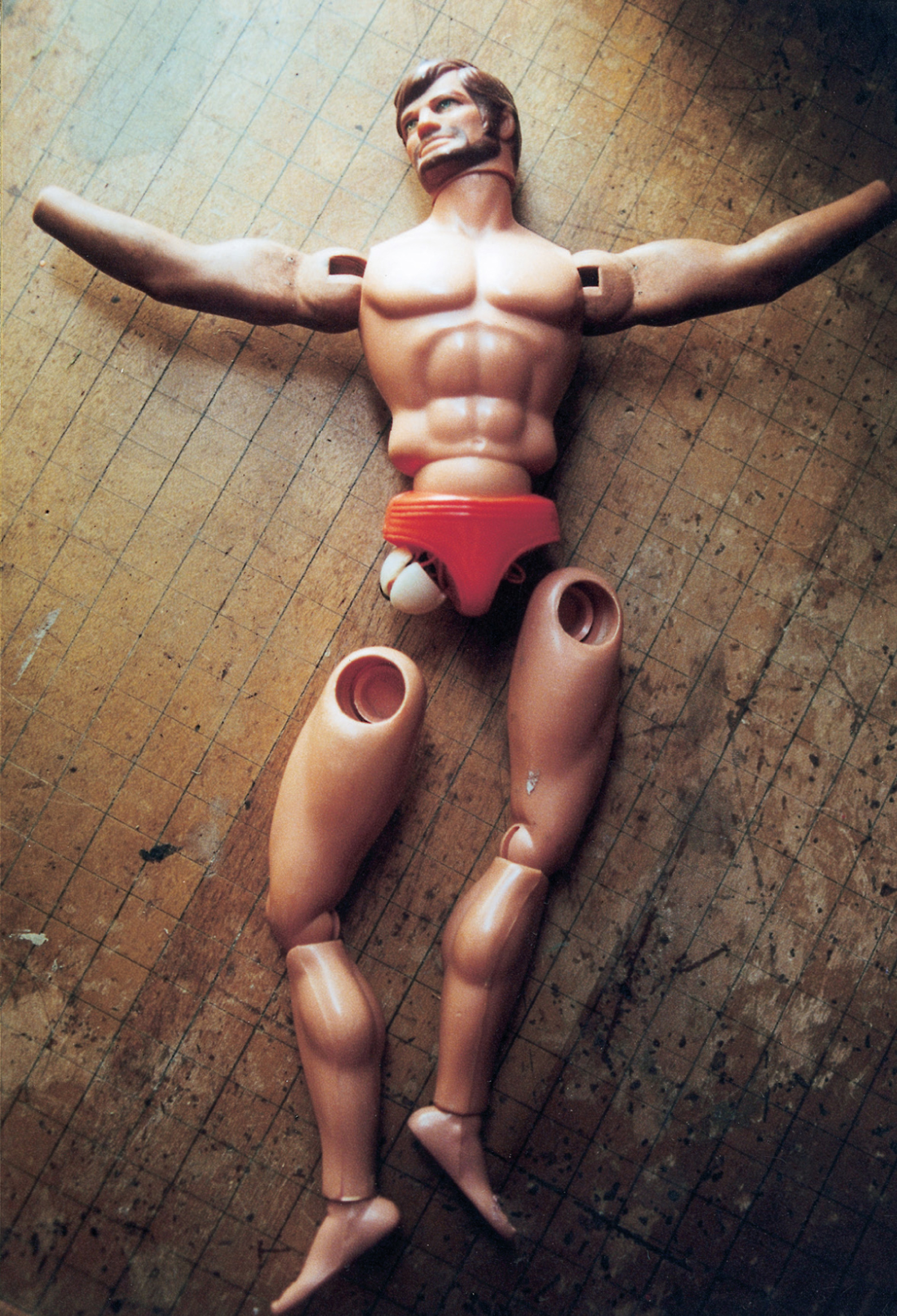

The Doll Games’ archetypical “manly man” with action arm, originally used to chop a plastic log (now lost). His name seems to gently parody his original identity as brawny lumberjack, “Big Josh.” In spite of his muscled torso, moustache, and the mature bulge in his plastic underwear, all of which marked him as masculine “other” to the youthful androgynes Laurie and Aina, and no doubt to the young Jacksons, Josh had a vulnerable quality. His legs dangled weakly from his loosely jointed hips, and later began to loosen and fall off, as did his hands and even eventually his left foot, making him a source of comedy, especially in the late farces, but also transforming him, in the end, into what we can only see as the Doll Games’ sorrowful, suffering Christ.

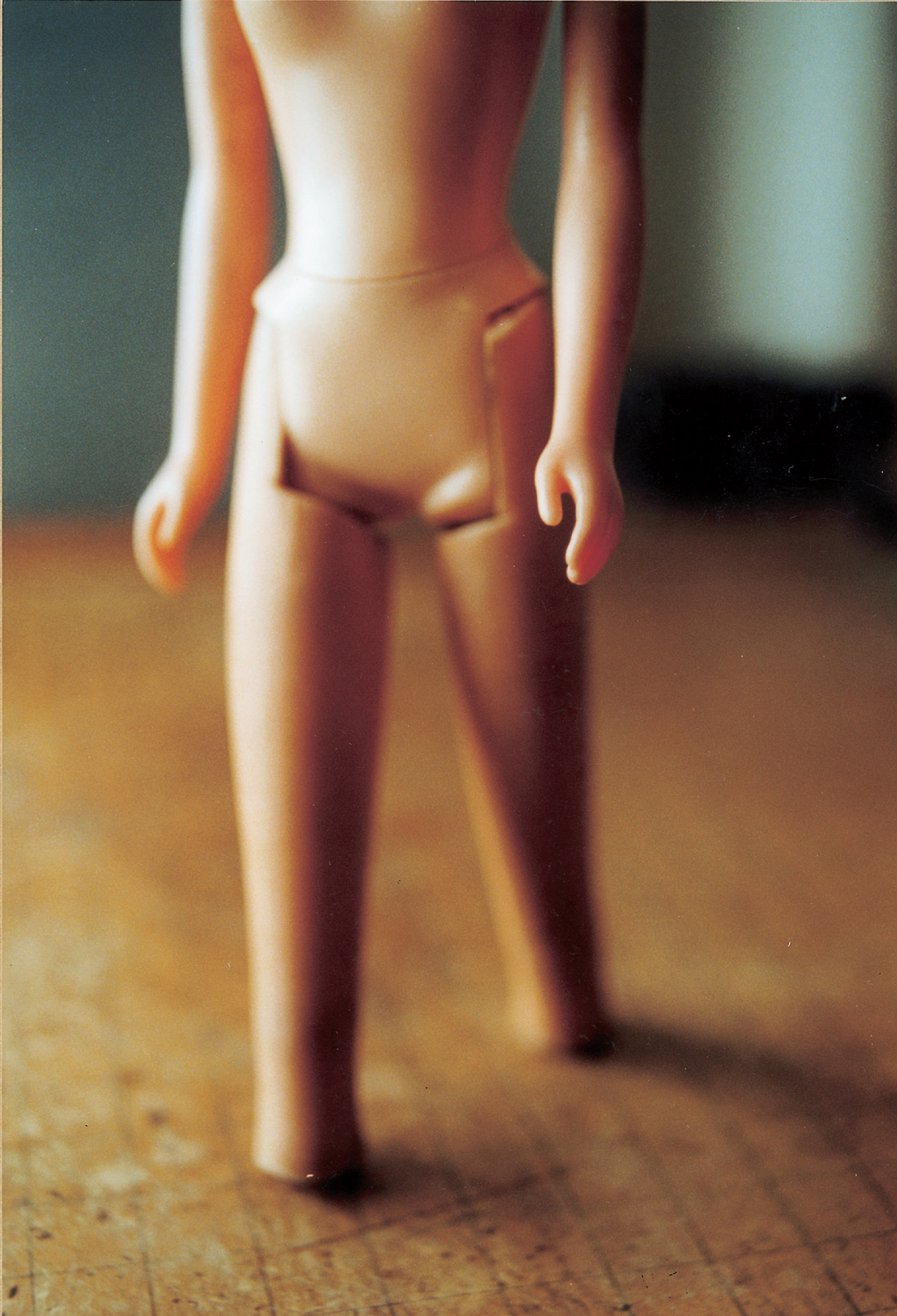

Long snubbed by the Doll Games, a “found” Barbie was finally admitted in the late classical period, on the condition that she suffer her trademark blonde hair to be dyed black, and her legs to be amputated just below the knees. Unfortunately, the offensive “blackface” and ungainly leg stumps that resulted from these operations made her a laughingstock, and she never found a lasting place in the Doll Games; her name, if she was given one, has been forgotten.

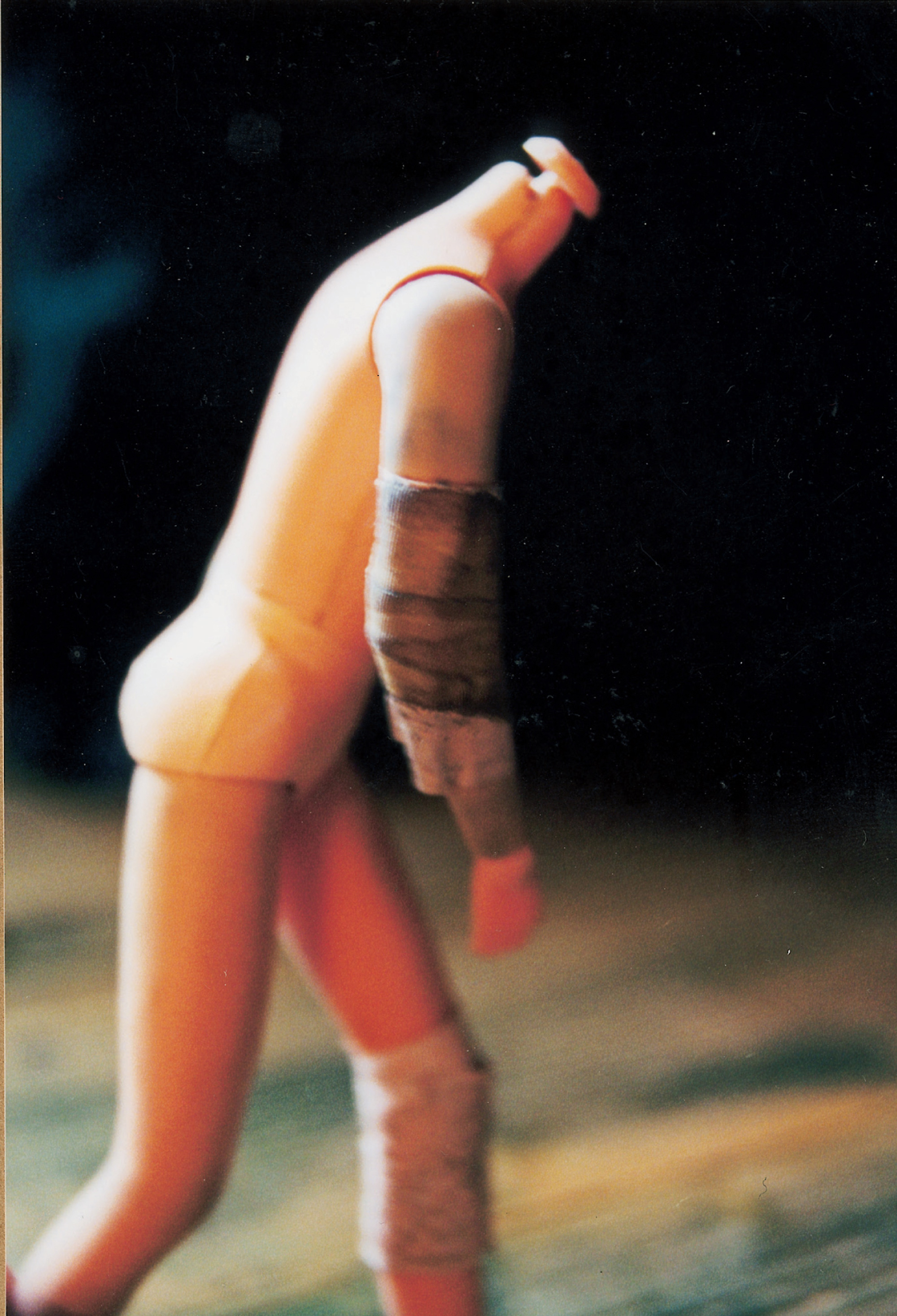

Dainty, wasp-waisted, and vain, reviled for her showy breasts and cheap feminine allure, Dawn was cast as the trashy “bitch/slut” of the Doll Games. Insinuating herself into the chaste plots of the virtuous heroes and heroines in order to seduce them into vice, Dawn was ritually vanquished and “put in her place” as the Doll Games’ cheerful moral order reasserted itself at the end of each game. A tendency, in keeping with her crass exhibitionism, to split in half, leaving her hips and legs naked on the ground, was deterred by a thick bandage of medical tape wrapped about her waist.

Poet and libertine, the Doll Games’ “horny fop” was originally a Little Red Riding Hood doll of unknown make. The combination of delicacy and swollen obscenity we see in his curious physique was matched by his personality: Harvey was at once tenderly lyrical and crudely predatory, both a hapless Romantic with perfumed hair and a goatish lout. His eternal amorous pursuit of the unreachable Mara and Melanie, interrupted by ferocious rutting with the likes of Dawn and Sue, was one of the great comic motifs of the late Doll Games.

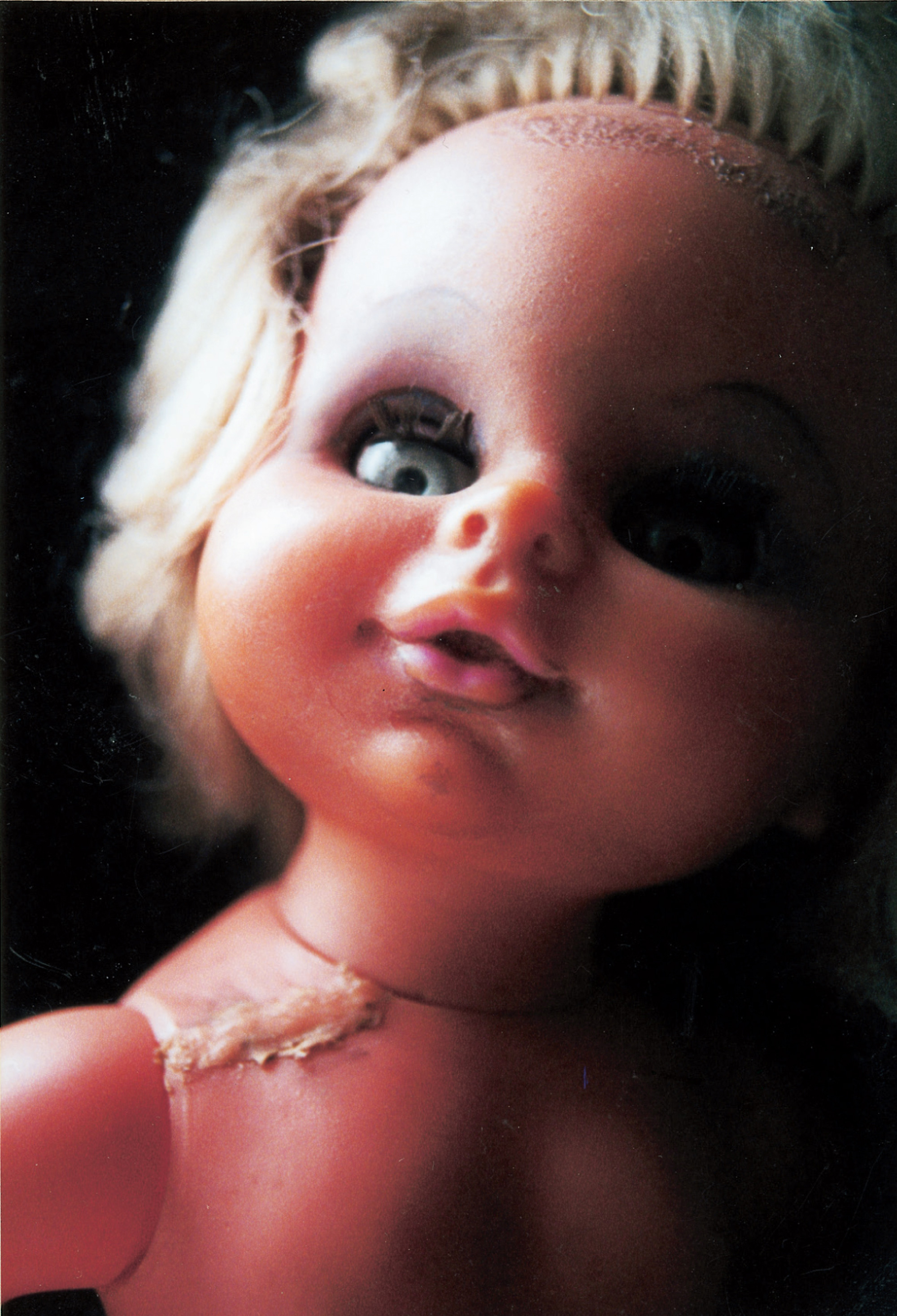

The Doll Games’ Sadean baby doll, a cruel voluptuary who presided over the orphanages and boarding schools of the so-called “nasty” games, corrupting virtuous boy dolls and jealously tormenting rivals Aina, Mara, and Melanie. At once mother-substitute and gargantuan infant, Matron was a key element in the Doll Games’ studies of the “maternal grotesque” as well as the “infant whore,” while the surrogate families she ruled became Oedipal laboratories in which the Doll Games conducted many of their boldest experiments.

Dreamy, gentle Jesse entered the Doll Games as a disembodied head, plundered along with Aina’s second head (or Aina2) from a matched pair of Scandinavian costume dolls. Initially sharing Laurie’s body and taking turns with him, just as Aina2 shared the body of Aina1, Jesse took over Laurie’s body and his role at Laurie’s death. Much remains to be examined in the original foursome, that intriguing set of doubly matched pairs in which we can see the “twinning” motif of the Doll Games worked out in its most complex and fatal form: one of these four blonde lovers/rivals, the lamented Laurie, perished in an attempt to dye his hair black that was seemingly motivated by the wish to differentiate and de-couple him from his siblings.

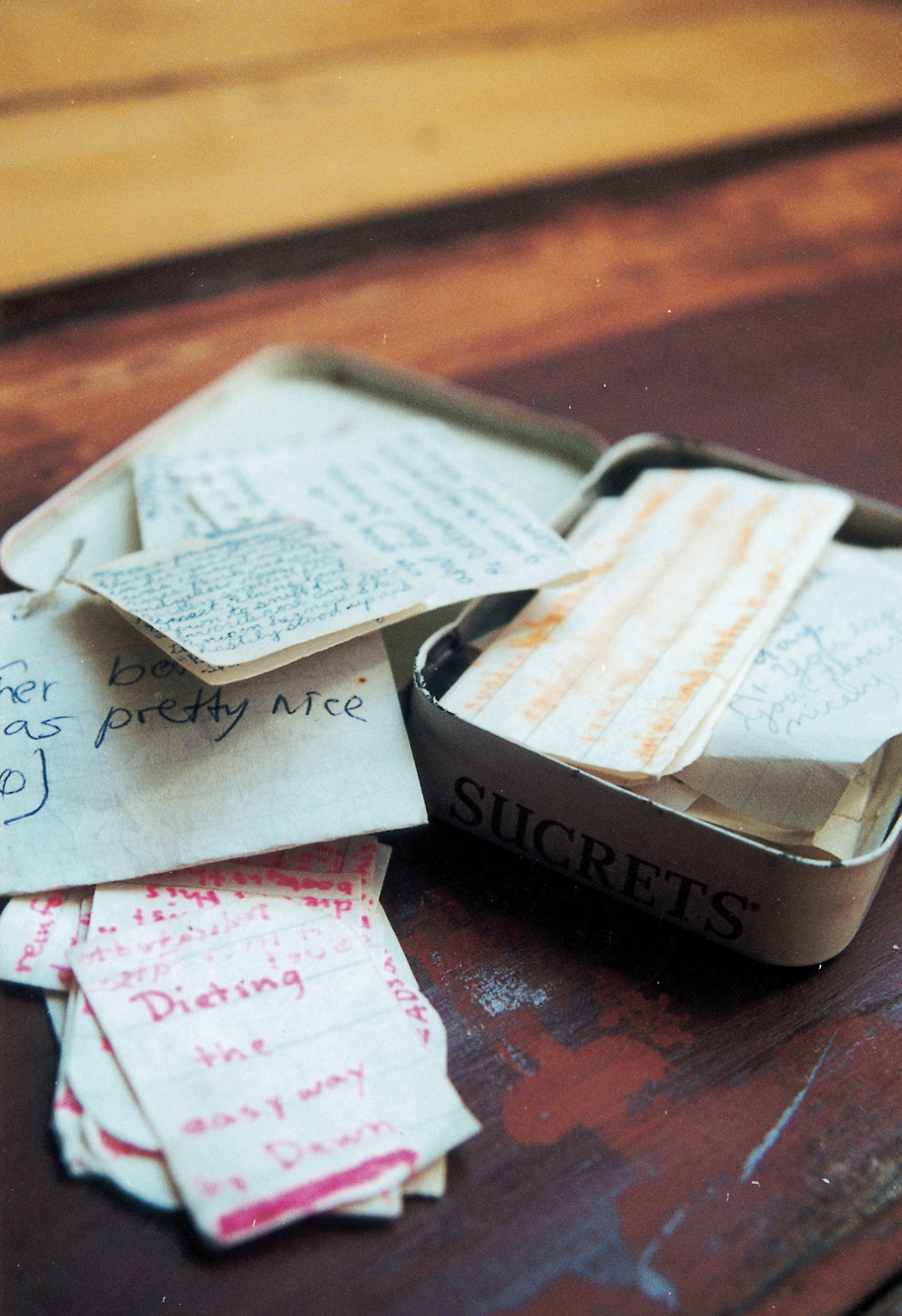

![A photograph depicting small modeled objects. The caption reads: Bathroom commodities in molded “plastic wood” decorated with magic marker to resemble name brands, including Desitin lotion (in pump dispenser), Stridex medicated pads, Secret deodorant, Noxzema, Band-Aids, Johnson’s Baby Cream, Suave Shampoo, Johnson’s Baby Powder, Coppertone, Sucrets, Johnson’s Dental Floss, [brand illegible] nasal spray, Buffered aspirin. Emblematic of the way the Doll Games consumed the larger culture, transforming and reconfiguring it for its own purposes, these jewel-like miniatures, none more than half an inch tall, are the products of thoroughly American dreamers.](/issues/9/cabinet_009_jackson_pamela_jackson_shelley_009.jpg)

1. Steel dagger made of a round-headed nail, half of which has been hammered flat to make a straight, narrow blade; the sheath is faux leather, folded and stitched up one side with telephone wire, the end of which is left loose to serve as a strap.

2. Aluminum dagger made of a length of wire hammered flat.

3. Bamboo dagger, whittled flat and tapered toward the tip. The grip is colored green on one side; a short hand-guard is affixed to the blade with white medical cloth tape. The blade fits snugly inside its sheath, which is real leather folded and joined with more cloth tape. A thin strip of fraying green cloth is taped to the top of the sheath; this once formed a loop for hanging, but is torn close to the sheath on one end.

Daggers, not all of them as finely crafted as these, were de rigueur for the heroes and heroines (above all the spunky Aina) of the Doll Games’ “Pirate” and “Outlaw” scenarios.

![A photograph depicting a piece of card with drawings on it. The caption reads: Poem printed in pencil (verse) and red magic marker (chorus) on inside of folded index card and signed by Harvey in pencil. On the other side of the card is a vivid semi-abstract mixed-media drawing (pencil, magic marker and white-out) with distinct sexual overtones, signed in purple marker by Harvey and with the title, “Mara and I” printed on it in red marker, as well as a redundant legend in purple identifying this as a “picture (abstract)”. The poem is a stellar example of that combination of sentimentality and ribaldry so characteristic of Harvey. Displaying his gift for drawing as well as poesy, and signed on both sides, this may be the most precious item in the collection.

Ah... Mara...

to feel you, warm and yielding

against my strong chest,

is bliss

Ah... Mara...

The glorious oneness I feel

with your innocent lips

upon mine, which I never

feel otherwise, (except when

it’s Melanie’s, Dawn’s, Philisses, anne’s [sic] or Jenny’s lips)

Ah... Mara...

to feel warm and peaceful,

after fucking long & vigorously

with you,

is an experience I will never

forget

Ah... Mara... My fair queen

of love...

I adore you.](/issues/9/cabinet_009_jackson_pamela_jackson_shelley_016.jpg)

Poem printed in pencil (verse) and red magic marker (chorus) on inside of folded index card and signed by Harvey in pencil. On the other side of the card is a vivid semi-abstract mixed-media drawing (pencil, magic marker and white-out) with distinct sexual overtones, signed in purple marker by Harvey and with the title, “Mara and I” printed on it in red marker, as well as a redundant legend in purple identifying this as a “picture (abstract)”. The poem is a stellar example of that combination of sentimentality and ribaldry so characteristic of Harvey. Displaying his gift for drawing as well as poesy, and signed on both sides, this may be the most precious item in the collection.

Ah... Mara...

to feel you, warm and yielding

against my strong chest,

is bliss

Ah... Mara...

The glorious oneness I feel

with your innocent lips

upon mine, which I never

feel otherwise, (except when

it’s Melanie’s, Dawn’s, Philisses, anne’s [sic] or Jenny’s lips)

Ah... Mara...

to feel warm and peaceful,

after fucking long & vigorously

with you,

is an experience I will never

forget

Ah... Mara... My fair queen

of love...

I adore you.

- I argue this point at greater length elsewhere; see “Did the Doll Games Ever End?” Postmodern Culture, MDXIXVIIIIIX.

- Per/forma 11, Summer 1998.

Pamela Jackson is an independent scholar. She is working on a book about Philip K. Dick.

Shelley Jackson is the author of The Melancholy of Anatomy, a collection of short stories, and Patchwork Girl, a hypertext novel.