The Wall and the Eye: An Interview with Eyal Weizman

Architecture and negative planning in the West Bank

Jeffrey Kastner, Sina Najafi, and Eyal Weizman

One of history’s most fiercely contested landscapes, the 2,270 square miles of territory known as the West Bank was under the control of Jordan when it was occupied by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War. Over the last 35 years, the area has become home to some 200,000 Israelis (400,000 including occupied East Jerusalem) who populate numerous, new, purpose-built settlements perched on its hilltops, overlooking long-established Palestinian lowland communities. This ongoing state-sponsored policy of expansion onto the high ground has been paralleled by the development, within the architectural and urban planning professions, of extremely particularized strategies for building on heights. Many of these draw on historical precedents; all are designed to provide basic municipal amenities within a context of highly refined, surveillance-based security.

A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, a catalogue and exhibition originally created by Israeli architects Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman as their country’s official entry to the 2002 World Congress of Architecture in Berlin, is a ground-breaking examination of the character of building, planning, and community in the West Bank. Abruptly cancelled last summer on the eve of the Congress by its commissioning organization, the Israel Association of United Architects, the project has stirred strong opinions in Israel. Although it was dismissed by the association’s president as “one-sided political propaganda,” A Civilian Occupation was praised as a “a rare work in its power and importance for the community of architects and town planners in Israel” by the daily newspaper Ha’aretz. Since the cancellation, Segal and Weizman have found other forums for the work they produced: the catalog is being reprinted by Babel Press in Tel Aviv and a version of the exhibition will be be mounted at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York, at the end of January and in the exhibition “Territories” at Kunst-Werke, Berlin, in May 2003.

In the following interview, Weizman, a partner in Tel Aviv-based Rafi Segal/Eyal Weizman Architects, discusses both the natural and built environment of the West Bank—from the social, political, and religious history of the area to issues of photography and mapping to concepts of strategic building forms and settlement growth patterns. He also asks pointed ethical questions about Israeli architectural and planning practice and considerations of human rights, which he says are central to the research he and Segal continue to conduct. Weizman spoke by phone to Jeffrey Kastner and Sina Najafi from Haifa, Israel, in October 2002.

Cabinet: Your catalogue cites a 1984 publication by the Israeli Ministry of Housing that sets guidelines for the construction of new settlements in the mountain regions of the West Bank. It’s very concrete: it proposes an inner ring and an outer ring of houses, discusses the idea of offering the maximal amount of views to the maximum number of settlers, which obviously also allows a maximum amount of surveillance of the Palestinian population beneath, and so on. This is interesting in light of the interview in your catalogue with the planner and architect Thomas Leitersdorf about towns he has built in the West Bank, where you get a sense that sometimes the government offers no guideline other than “We need a town built here,” and the architect is completely left on his own to do whatever he wants. So we have this severe set of guidelines versus no guidelines at all, apparently at the same time.

Eyal Weizman: When Leitersdorf built Ma’ale Edumim in 1977–78 he was in effect setting the guidelines. Ma’ale Edumim was essential in creating a benchmark standard for building settlements. In general, Israeli architects and planners had little experience of building in mountainous regions. Before the occupation, the Israeli population was located mainly in the valleys, except in Haifa, which is a mountain city, and in Jerusalem. The typical new Israeli settlements were the kibbutz and the moshav, cooperative agricultural and pioneering settlements built mainly on the fertile plains. It is only after the occupation, and following the political changes in 1977, that the mountain enters the public imagination—people write songs about the mountain, talk about it, lecture on it, research it. Architects were starting to think about the mountain too, but they had little experience of building there. So this publication by the Ministry of Housing was incredibly important because it collected different precedents and for the first time set guidelines for how to build in the mountains. The “mountain” is important in understanding the ideological transition in Israel after 1977, when a messianic religious discourse entered the political debate with the right wing coming to power. Along with it came a decreasing emphasis on agricultural pioneering and its replacement with a new typology of the religious suburb, located on mountaintops and without agricultural space to cultivate.

What are the historical sources for this relationship to the mountain?

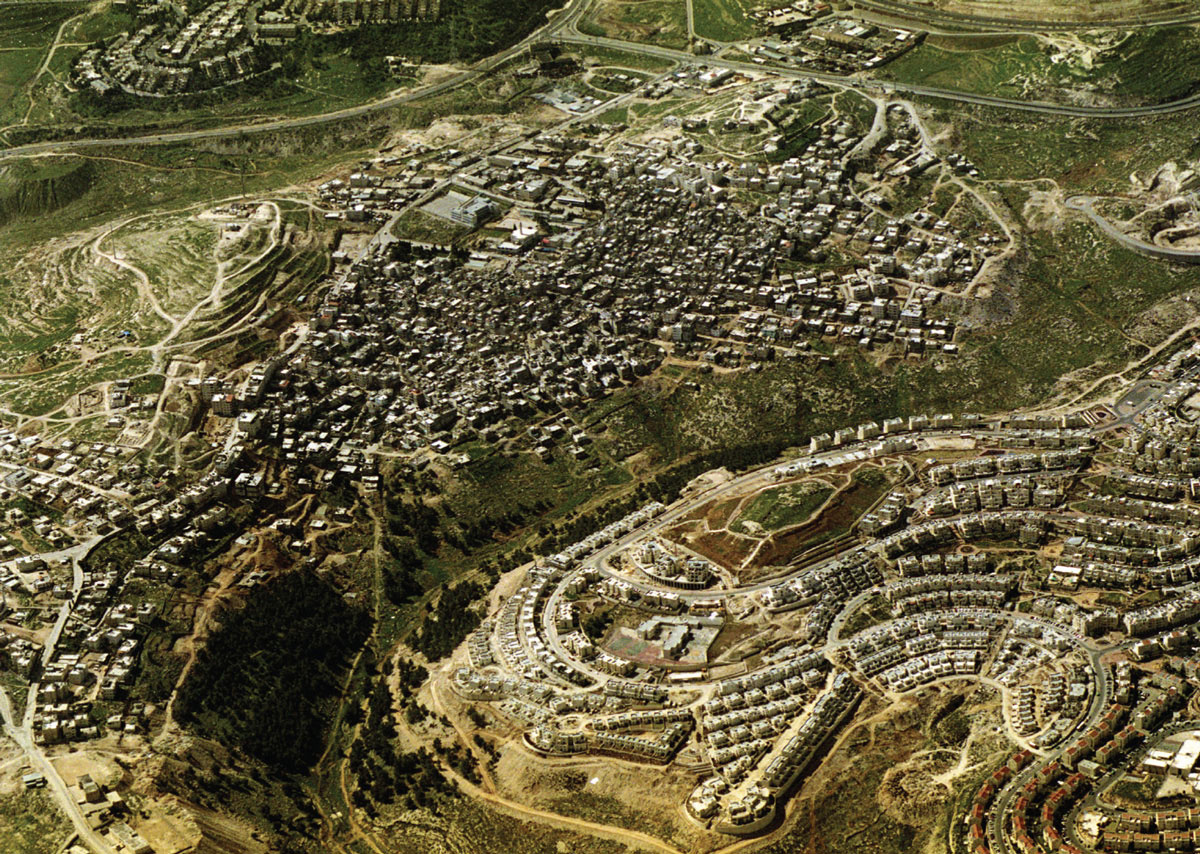

If you look at the geography in Biblical times, the Israelite settlements were primarily in the mountain regions of Judea, Samaria, and the Galilee, whereas the plains were inhabited by the Philistines. So there is a geographical reversal, a paradox: when the Zionists came back to their “promised land,” they initially settled in the places where Jewish history didn’t happen within the land of Israel. The return to the mountain is a return to those sacred places, to the bedrock of Jewish identity. At this point, the mountain appears in many aspects of culture as a symbol and as an unfamiliar reality, and architecture is part of it. The government wanted to resettle the mountain and architects needed to learn how to build there, so the Ministry of Housing came up with guidelines that promoted the use of topography for the establishment of observation points. These were new urban typologies that maximized the potential of the mountain and made use of the precise morphology of the topography. Basically, if you look at the master plans of the settlements, the roads retrace the topographical lines that we charted on maps, so that each settlement takes the exact form of the mountain summit and is built around it as a ring that overlooks all directions. It’s most clear in Ma’ale Edumim, where there is not just one peak but many peaks and ridges. There you see the direct translation of topographical cartography into urban form.

Since mountaintops are not suited to agriculture, presumably many of the settlers are commuting.

Yes. Essentially, the settlements are built there because the mountains are not suited to agriculture. It is because Palestinians could not cultivate these hilltops, where the good alluvial soil has eroded, that they could be seized by Israel and declared state land. It’s a complete reversal of the logic of cultivation. Obviously the settlers have to either rely on the main cities—the metropolitan centers like Tel Aviv and Jerusalem—or on industrial zones near the settlements, again on hilltops.

Are those industrial centers subsidized?

They are subsidized in the sense that you pay much lower income tax and council tax.

You describe an important evolution toward a kind of messianic political ideology. What was going on in 1977 that specifically catalyzed this shift?

The crisis point in Israeli history was 1973 and the Yom Kippur War. This was a time when the Israelis were fearing total defeat and old fears resurface. Until then, Labor Zionism was trying to reverse the traditional image of the Jew—not as a victim, but as a strong, self-sustainable new man. This exemplified itself even in the way the Holocaust was portrayed and sometimes even glorified as an act of national resistance. The national day of Holocaust remembrance, for instance, is called the Day of the Holocaust and Heroism. In 1973, Zionism experienced “the return of the repressed,” with a renewed sense of doom, as the Egyptian and Syrian armies seemed to be driving toward the main urban centers, with only the incredible maneuvers of Ariel Sharon in the Sinai stopping them. But immediately after the war, with Golda Meir’s government in ruins, you see the religious elements in Zionism taking control. One of the first settlements, Sebastia, was created by Gush Emunim, which is a kind of religious organization that has always pulled the government by the nose to build settlements, as if to uplift the gloom of the Yom Kippur War. It took four more years for the Labor government, which had controlled the country from its creation, to be replaced by the right-wing Likud government of Menachem Begin. And the whole settlement policy changed—they discovered the mountain, sacredness, and archaeology again.

By this point presumably the left’s political clout had been much diminished. Were the settlements presented as a fait accompli? Was there a great deal of internal debate in Israel about this program of settlement building?

It was always very controversial from its inception.

But was it presented as a security issue or was it presented as an ideological, religious issue? Or are the two things so tied up together that you cannot pull them apart?

You have all the reasons at play together; sometimes some are stronger, sometimes others. In the first 10 years after the occupation, 1967 to 1977, we had a Labor government. What they did mainly was to settle the Jordan Valley with kibbutzes and moshavs—this is what they knew, frontier settlements on the plains. Between 1973 and 1977, it was Shimon Peres who was supporting Gush Emunim. Shimon Peres was squabbling with Yitzhak Rabin for the hegemony of the Labor Party and he aligned himself with the right-wing policy of establishing settlements just in order to embarrass Rabin. So Peres was actually the first person to promote settlements even before the beginning of “the mountain ideology,” before the reversal of power. As for security, up until 1979 the legal tools that the government used in order to seize land and build settlements were based on the 4th Geneva Convention, to which Israel is a signatory. The convention states that you are not allowed to build permanent settlements on occupied land, but you are allowed to build temporary interventions for security reasons. What the government was claiming was that the settlements were temporary paramilitary posts.

This issue was debated twice in the High Court of Justice (HCJ). There were petitions by Arab landowners against the confiscation of their land and the building of settlements. The first one was the case over the Beit-El settlement, which produced an incredible protocol, with the HCJ judges debating urban form in terms of military-strategic potential and speaking in terms of vision and observation. The HCJ in that instance allowed the construction of these settlements, with the Israeli High Court Justice Vitkon at one point declaring that, “With respect to pure military considerations, there is no doubt that the presence of settlements—even if ‘civilian’—of the occupying power in the occupying territory substantially contributes to the security in that area and facilitates the execution of the duties of the military. One does not have to be an expert in military and security affairs to understand that terrorist elements operate more easily in an area populated only by an indifferent population or one that supports the enemy, as opposed to an area in which there are persons who are likely to observe them and inform the authorities about any suspicious movement. Among them no refuge, assistance, or equipment will be provided to terrorists. The matter is simple, and details are unnecessary.” Here the court is clearly establishing the fact that civilians and residential settlements could have a security function that is normally attributed to the police and the army. The next case in 1979 was that of Elon Moreh, where the settlers practically shot themselves in the foot by claiming they were not there for security reasons but because it was their right and this was their God-given territory. This meant that the court could no longer authorize the settlement as a temporary military intervention.

They were testing this new theoretical definition of what a settlement could be, which was not related necessarily to this temporary security-based issue, but was related to some kind of divine right?

Yes, the settlers felt that as long as the settlement project was judged only on strategic issues they were going to lose their credibility as an ideological-religious movement. And if other security arrangements were found, they could always be evicted. They chose a strategy but ultimately lost the case and the settlement was destroyed.

But did that lay the foundation for future claims?

The government had to opt for another legal tool because they could not build settlements and argue that they were temporary strategic military outposts. They said, OK, we can rely on Jordanian law and start a project of land registry. The West Bank had not had a land registry since Ottoman times, and if you look at Ottoman land laws, you did not have real land ownership. You would just pay tax for what you cultivated. Nobody wanted to own anything beyond what he was growing on, because that is what you paid tax on. If someone fenced off a hilltop, he didn’t register it because that would just mean more taxes. So basically Israel was collecting Ottoman tax documents to establish ownership and map out the extent of cultivated lands. Whatever land could be proven to be under continuous cultivation remained in private Palestinian ownership, and the rest was declared state land according to Jordanian law, which was based on Ottoman law.

But legally, didn’t the Israeli government have to say that the West Bank is actually their land in order to then impose a set of rules on it, no matter where they borrowed those rules from?

What they were saying was that these patches of land here and there, mainly the hilltops because the hilltops were not being cultivated, were State of Israel land. They were state land because they were not under any private ownership, and Israel was the ruler of the area. There were complaints at the UN that Israel could not use state land in the way they wanted to because it was still under temporary possession of an occupying power. But Israel claimed that the West Bank was not actually “occupied land,” because the UN never recognized Jordanian sovereignty over the West Bank. It was a very complex, self-contradictory and elliptical way of arguing. On the one hand, Israel accepted and relied on the Jordanian rules. On the other, it said something that is in fact true, that the West Bank was occupied by Jordan after 1948 but that the UN had never recognized its sovereignty there.

You write about how after 1967 this contested land in the West Bank became one of the most photographed terrains in the world, where 3-D stereoscopic images were constructed using special double-lens aerial cameras. Are the new aerial photographs you’ve included in the catalogue similar to the ones the Israeli government took after 1967?

Not at all. These are photographs taken by Milutin Labudovic for an organization called Peace Now in order to monitor settlement growth. They are taken at low altitudes—we were allowed to fly at 6,000 feet over sea level. The stereoscopic images were essentially 3-D reliefs of the terrain taken at a much higher altitude in order to build topographical maps. Right after the occupation, the government needed to create a map very quickly, and it was difficult to physically get to all the places, so they used this stereoscopic technique in order to recreate the structure of the mountain. Before the occupation, there were no good topographical maps of the area—there were some done by German and American evangelists who were mapping the Holy Land and some general ones done by the British mandatory power, but they were absolutely not good enough to plan and construct with. What interested Rafi Segal and me about the stereoscopic technology was that a methodology of design so clearly relied on a technical apparatus—the stereoscopic images became the primary tool with which topographical lines were charted on maps and then provided the slate for the design work itself. The desire to map the West Bank immediately after the occupation showed clearly that you don’t just map things—mapping is an act of proprietorship and the whole settlement project is built upon those topographical lines, which were drafted on those photographs. It’s as if those lines set the blueprints of the settlements.

Was it difficult to obtain permission to take your aerial photographs?

It is very difficult now after operation Defensive Shield, but previously the Ministry of Defense was allowing us very narrow slots, over the air space the Israeli air force was using and underneath the national routes.

Your aerial images show a number of striking things about the details of the landscape, which nevertheless need to be “read” with guidance. One was the politics of pine trees versus olive trees. The Ottoman rules were that the state could acquire any land that had not been cultivated for a certain amount of time. So now the Palestinians are rushing to plant olive trees and the Israelis are planting pine trees, which grow a lot faster.

That’s true, but it’s not only that they grow faster. Another reason for planting pine trees is to make a difference from the olive tree as a separate national symbol. A third reason is that pines have an acidic drop on the ground. There are no bushes under pine trees, so grazing and shepherding is very difficult in these areas that have been planted with pine. Even if you cut the pine trees, the subsequent acidity of the land is such that it does not allow agricultural cultivation. Right now we are working on an enlargement of one particular image—in a similar fashion to the kind of work that intelligence analysts do during wartime. They can see things that the untrained eye cannot. We try to reveal the hidden narratives engraved on the landscape.

I think that’s important because one of the things our editorial group discussed when we were looking at the aerial photos is the degree to which they aestheticize the information. It sounds like the project you are working on now is one of particularization—putting specific information along with the images. That seems to make a strong case for these kinds of images that are very beautiful but with which the viewer has a strange relation in terms of the contrast between their aesthetic qualities and the information they contain.

That is true, but beauty has an incredible political significance in the context of this conflict, and we tried to show it in these terms. When we talk about the panorama in terms of the picturesque and the pastoral, we claim that, in fact, beauty is thought of as both a commodity and a strategy in terms of the views from the settlements. It is there to draw the settlers in and ever closer to the Palestinian communities (which produce this beauty)—like a moth to a flame. It is a guiding principle that the settlements are urbanistically laid out in order to maximize the view. There is a paradox in this beauty in that what is considered by the settlers to be a pastoral, romantic panorama is actually the traces of the daily lives and cultivation of the Palestinians, and the settlers both enjoy that view but simultaneously supervise it. The settlers obviously have a very ambiguous relationship to this. On the one hand, the view creates for them a kind of biblical landscape that they admire, a way of life that seems to them more authentic. Yet they are, in fact, there to destroy and replace it.

It was also interesting to see the physical relationships of the settlements and the Palestinian towns—how close they sometimes are to each other and how different the building forms were, although, in the more close-up photos you could see some similarities, too. When you look at a Palestinian village near a settlement, many times you’ll see that the houses that are very near to the fence—nearest to the settlement—imitate the red roofs of the settlement, usually with red painted asbestos placed on their flat roofs. So, for example, the architectural sign of a red roof, which for the Israelis is basically a rural, suburban idea of the home, is for the Palestinians a sign of progress, modernity, and luxury—everything they strive for and want to emulate. It is very strange. When you drive through the West Bank, you see the great influence of settlement architecture on Palestinian architecture, and vice versa. In a sense there is a kind of disturbing mutual admiration stretched along the double-poled axis of vision. The settlers try to learn from the Palestinians how to live in nature; they see the Palestinians as the authentic component there, something that they would like to be but cannot.

But in Israeli architecture, that trope of the red, sloped roof is itself a really displaced kind of beauty—a borrowed European, almost Tyrolean, form that in its right context has a purpose but here is not at all suited functionally to the environment.

It functions in the settlements as a sign. Many times, settlement building codes require that anyone building their own home must build with this red roof because it’s a sign that differentiates the “us” from the “them.” And I have heard of a residents’ meeting where settlers tried to resist the red roof—saying it’s a misplaced European element, etc.—while people from Gush Emunim, the main settler body, forced them to build them if only to show Jewish presence. Before the Intifada, when you could still go into the West Bank to Palestinian hummus restaurants, they would quite often have wallpaper of, say, a Swiss landscape on the whole wall. Out the window you could see an equally, or even more, beautiful landscape, but the “ideal” was somewhere else—in Switzerland, somewhere in the West—not where they were.

In addition to the photographs, the catalogue has an aggregate map you’ve put together of all the different settlements. Is that information itself contested by the Israeli government? Or was the compilation the difficult part of the process?

This map is a joint project between myself and the human rights organization B’Tselem that was done in the context of a human rights report on violations through architecture and planning. Nobody contests its accuracy, and some in the Israeli establishment even work with it. I’ve recently heard that even some settlers’ organizations use it. Last summer we presented it to the American administration, to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, to the State Department, and the Pentagon. They checked it and verified it and are now working with it. That is a great achievement for us. Conducting policy with this map is something we think is going to inevitably change the discussion.

Whose maps were used before? Did the Palestinians present their own maps of the settlements at the peace negotiations? Were there two competing versions of reality offered?

The best source for mapping the West Bank was always the CIA. A few times a year they took satellite photographs of the West Bank and produced a kind of status report on the built fabric of the settlements. These were usually classified for a period of time and then released. The novelty in our map is that we actually took and were able to trace almost all the master plans for future settlement growth. These supposedly have to be published, but obviously the government and the regional councils do not have any interest in the Palestinians knowing the master plans. The government is bound by law to make the documents public, so they post them within the settlements, which the Palestinians obviously cannot enter. When we sent letters asking to review the master plans, the councils threw a lot of obstacles in our way and we finally had to threaten them with a petition to the HCJ. Then they gave us some maps, but always old maps, and then they’d say, “Oh, sorry.”

What is the government worried about in terms of what the maps revealed?

Well, the expansion of settlements is guarded almost like a military secret.

So it was less a question of the identification of the settlements as they are than the projections of what the settlements will turn into?

Exactly. This is a map of a possible future of the settlements and of the West Bank.

What general conclusions did you draw from the map when you actually saw it, either ideologically or in terms of planning issues?

Most other maps of the West Bank show the settlements as points. They show the location, perhaps the number of settlers in them. But by actually showing form, we were trying to make a connection between the very organization of matter across the landscape and human rights violations. So it’s not only the fact that settlements are there, but it is the forms of the settlements—their shape, and size—that are contrary to human rights. For example, if you look at Ariel, which is an urban settlement located west of Nablus, it has an elongated banana shape. This is something you don’t see in a map where it’s depicted as a point. And you ask yourself, “Why was the settlement built like that?” If a student of ours came up with a plan of a city like that, we would say, “You must be joking! It maximizes traffic, does not allow pedestrians to walk, does not serve the population.” So there must be other considerations involved. You start breaking down the formative forces that operate on the form of this stain on the map. On the one hand, the settlement wanted to stretch itself as long as possible along Route 505, which is one of the most strategic east-west arteries, an artery that Israel believes would have an armed column going down it in the event of a Jordanian or Iraqi invasion from the East. So the settlement spreads thin as long as possible along that road. On the other hand, it creates a complete wedge across the north-south axis and separates Salfit, which is a regional Palestinian center, from the villages to its north that rely on it for their economy. Another thing that it does is envelop Salfit and prevent it from growing in the direction it would like to. All these are done by formal manipulations, decisions taken by architects and planners—something that shows that we have here a policy of negative planning.

In architecture lingo, we call this weak form. Weak form reacts to a kind of force field that operates around it. Imagine a drop of water that is running on a particular surface and it reacts to the surface—in this case, to topography, but also to the temperature of the surface, its slope, air flow, etc. There are many political and strategic forces that stretch the forms of the settlements one way or another. The very forms embody the momentary balance of forces that created it. What Rafi Segal and I did at our office was to try and read backwards from the form of the stain on the map in order to recreate and understand the forces that manipulated it. With this method of observation, you can see the objectives of the planner. This is our point: It is not only that the settlements are there. If that were the only case, you could argue that it is not the responsibility of the architect and only of the political decision that placed it. But when the form is designed in a particular way to achieve strategic and national goals—bisect a Palestinian road, surround a Palestinian settlement, or to try to create a wedge—the architect is engaged in negative planning, a reversal of his professional practice—like a medical doctor involved in torture. This approach establishes architecture, just like the tank, the gun and the bulldozer, as a weapon with which human rights could be and are violated. The mundane elements of planning and architecture are placed there in order to disturb and dominate, and when an architect is designing in order to disturb the growth of other things, he’s not acting as an architect.

You would say it is unethical.

This is completely unethical! And it’s not architecture. If there are violations of human rights in the plans the architect is proposing—in the way he is designing the houses, in the orientation of the windows, in every detail on both the architectural and the urban scale—then these actions are unethical and illegal. This incriminates the architectural profession. If the architect were just ignoring the Palestinians, it would look completely different. This is much worse. This is why there was a huge controversy here with the publication of A Civilian Occupation. Basically, the architects were like Leitersdorf—liberal, educated, most often Labor supporters who see themselves as building in the West Bank in a way that best serves the Jewish population there. But that is obviously not true. And we were trying to break out the reasons for why the forms are the way they are and reflect from that backwards on the whole ethics of architecture in Israel.

So when someone like Leitersdorf says, “I was given no criteria, but I came back with three sites that took into account air pollution, traffic, commuter routes,” and so on—is it your opinion that all of those criteria hide some other criteria that he’s not willing to confront?

Obviously. If you look at the 1984 government guidebook, it only speaks of the view. But what is this view? Is it simply the pastoral, Biblical landscape that you want to provide every citizen? No, because when you read the larger scale master plans outlining regional strategy, you see how they value observational points, and that their plans lay out a net of visual control vis-à-vis the Palestinians, the roads, and the strategic arteries. The overall master plans of the army and the settlement body are at least more honest in their aims than the architects. The architects themselves are not willing to admit to it, so they internalize those regional principles but argue for them in a completely different way.

Eyal Weizman’s “Politics of Democracy”; www.opendemocracy.net/

debates/article.jsp?id=2&debateId=45&articleId=801 [link defunct—Eds.]

B’Tselem: The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories

Map of West Bank settlements; www.btselem.org/English/Publications/

Summaries/Land_Grab_Map.asp [link defunct—Eds.]

Eyal Weizman is an architect, based in Tel-Aviv and London, who has conducted research on behalf of the human rights organization B’tselem on the planning aspects of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. Weizman is currently developing his doctoral thesis “The Politics of Verticality: Architecture and Occupation in the West Bank” into a TV documentary film and a book to be published next year.

Jeffrey Kastner is a Brooklyn-based writer and senior editor of Cabinet.

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief of Cabinet.