Does the Proletarian Child Need a Fairytale?

The Soviet-production book for children

Alla Rosenfeld

In the aftermath of the 1917 Revolution, the Bolshevik regime regarded children’s books as major vehicles for transmitting Soviet ideology and influencing the new generation. Children’s literature would impress upon young readers of the post-Revolutionary epoch, many of whom belonged to the working class and peasantry, the need to become active participants in the building of the Communist state. On 1 November 1917, the People’s Commissariat of Education (Narkompros) decreed that the Soviet state should achieve general literacy as soon as possible by introducing obligatory and free education.[1] As discussed in “The Forgotten Weapon,” published in a February 1918 issue of Pravda, children’s literature would serve an important function in the class struggle:

In the great arsenal with which the bourgeoisie fought against Socialism, children’s books occupied a prominent role. In selecting cannons and weapons, we overlook those that spread poisonous weapons. So focused on guns and other weapons, we forget about the written word. We must seize these weapons from enemy hands.[2]The issue of children’s literature engaged Communist Party leaders at the highest levels, including the Commissar of Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky, and Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya. It also captured the imagination of leading Soviet avant-garde artists, such as Vladimir Lebedev, El Lissitzky, Aleksandr Rodchenko, and David Shterenberg. Throughout the 1920s, such figures designed highly experimental children’s books that embraced the principles of contemporary art movements such as Suprematism and Constructivism, and were not only propagandistic tools but also innovative artworks in their own right.

Discussions about children’s books were carried out within the broader context of the spectacular transformation of the Russian educational system in the aftermath of the Revolution. American pragmatism, in particular the theories of John Dewey (1859-1952), greatly influenced the Russian school programs of the early 1920s. The Soviet adherents of Dewey’s theories claimed that the task of the school was not to educate but to create the conditions for the development of useful skills. Courses in religion, ancient languages, and ancient and medieval history disappeared from the curriculum.

In the pre-Revolutionary era, children’s literature primarily consisted of fairytales, legends, and fantasy stories. However, as if in response to the tremendous social changes that accompanied the Bolshevik upheaval, the years following the Revolution saw a rapid, marked decline in such themes. While folk legends and fairytales constituted approximately 25 percent of all children’s books in 1918, they represented only 5 percent of them the following year.

The appropriateness of fairytales for Soviet children’s books was a subject of intense debate during the 1920s and 1930s. Many Soviet educators deemed fairytales incapable of accomplishing the tasks assigned to children’s literature in the new epoch, while others defended their social value. The former condemned the fairytale as emblematic of the old regime, regarding it as a literary genre that contained elements of mysticism and religiosity and led children into the world of dreams—impediments to the goal of introducing young readers to the themes and subjects of contemporary life. Opponents also believed that fairytales reflected the ruling-class ideology of the eras in which they were created. Since many tales preached loyalty to kings and included religious superstitions, numerous Soviet pedagogues regarded it as virtually criminal to introduce proletarian children to ideals that had no place in a socialist society.

In her 1925 book Does a Proletarian Child Need a Fairytale?, the pedagogue E. V. Yanovskaya, one of the leading authorities on preschool education, focused on the fairytale’s role in child development from the perspective of class consciousness. She argued that the fairytale acted as an obstacle to the child’s understanding of historical materialism and called for the abolition of the genre. Describing fairytales’ improbable (occasionally impossible) plot developments—old men turning into young men, stupid people turning smart, and poor men becoming rich—she concluded, “The bourgeoisie needs these fairy tales to support their exploitation. Fairytales are needed so children who are hungry and cold can escape into the world of fantasy and feel imaginary happiness.”[3] Criticizing the story of Cinderella, for example, Yanovskaya argued that it was “a political catastrophe in the upbringing of a new generation” for children to have a sympathetic attitude toward this heroine.[4]

To replace the disgraced fairytale, Soviet writers introduced a new genre: the child-oriented production book. The production book addressed themes that reflected the importance of modernization in Soviet society, focusing on science and technology, the central components of the First Five Year Plan, construction and urbanization, and the conquest of nature. Several thematic groups developed within this genre, including stories about mass production, various professions and trades, different types of machinery, and agriculture. Many Soviet critics argued for the social importance of the themes. The most highly regarded theme was industrial development, while topics such as the production of cosmetic powder or women’s fans were dismissed as unworthy of treatment in book form.

Another requirement for production books was that they celebrate technology’s progressive potential. This feature would help distinguish Soviet publications on modernizing, industrial themes from their pre-Revolutionary predecessors and Western counterparts, which, the Soviet critics of children’s literature presumed, described the oppressive and alienating labor of capitalist societies. In 1935, the Soviet critic G. Eikhler wrote:

The first and primary requirement for Soviet children’s books on science and technology is a clear demonstration of the principal difference between socialist and capitalist technology.… The blast furnace of the Communist state is totally different from the one of capitalist society since in the West it furthers the exploitation of the working class while in the USSR it is a means of strengthening Socialism.[5]

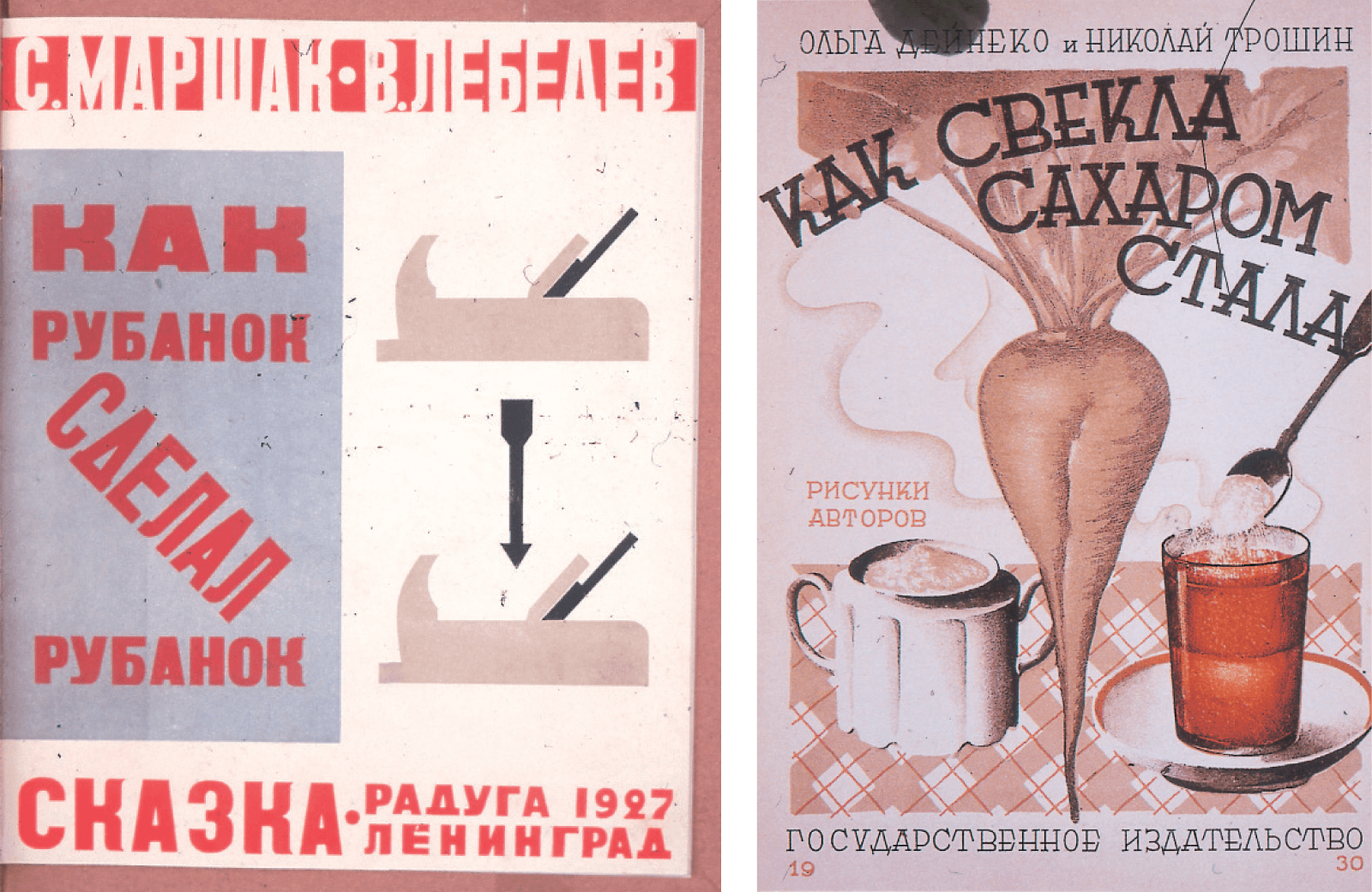

Left: Cover of How the Plane Made the Plane (Leningrad: Raduga, 1927). Right: Cover of How Beets Become Sugar (Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo, 1930). Both titles translated from the original Russian.

• • •

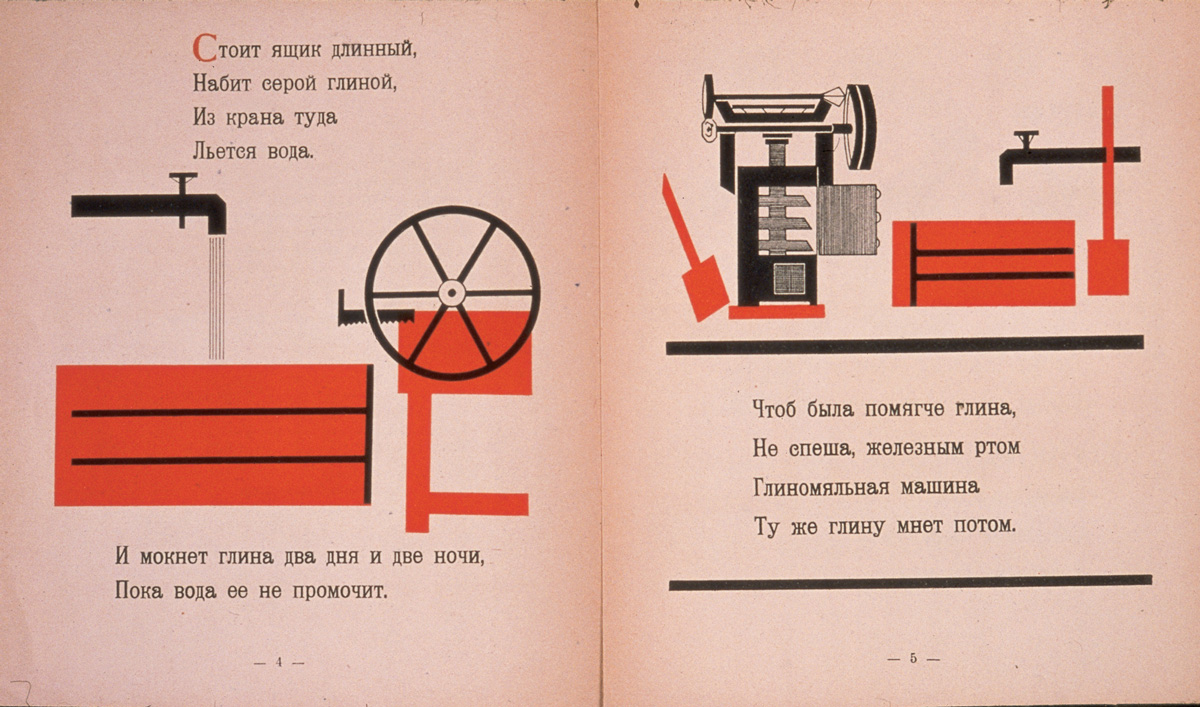

During the second half of the 1920s, the production book became one of the most important art forms of the Constructivists, many of whom, unable to implement their innovative ideas in industry and architecture because of material scarcities, turned to graphic design. Their works combined ideas from abstract painting with experimental typography to create a new visual language of Soviet children’s book design. Among the first successful experiments was the work of two Moscow-based artists, Galina and Olga Chichagova, who in the 1920s were students of Aleksandr Rodchenko at VKhUTEMAS (Higher Artistic Technical Studios). Between 1923 and 1929, the Chichagova sisters produced around 20 books, many in collaboration with the writer N. G. Smirnov. Often created with a compass and ruler, the sisters’ designs embraced the Constructivist machine aesthetic, featuring straight lines and schematic, elementary forms that resembled technical drawings and corresponded to mechanical printing. In the 1924 book Where Do Dishes Come From?, they depicted the stages of dish production. Although the workers are mentioned a number of times in the text, they are absent from the Chichagova sisters’ illustrations, which focus on machinery and production tools. While one contemporary reviewer described the book as “quite boring” and “lifeless,”[6] another reviewer, Anna Grinberg, herself a children’s author, praised it as “precise and to the point,” “devoid of sentimentality,” and “capable of holding a young reader’s interest without resorting to fables.”[7]

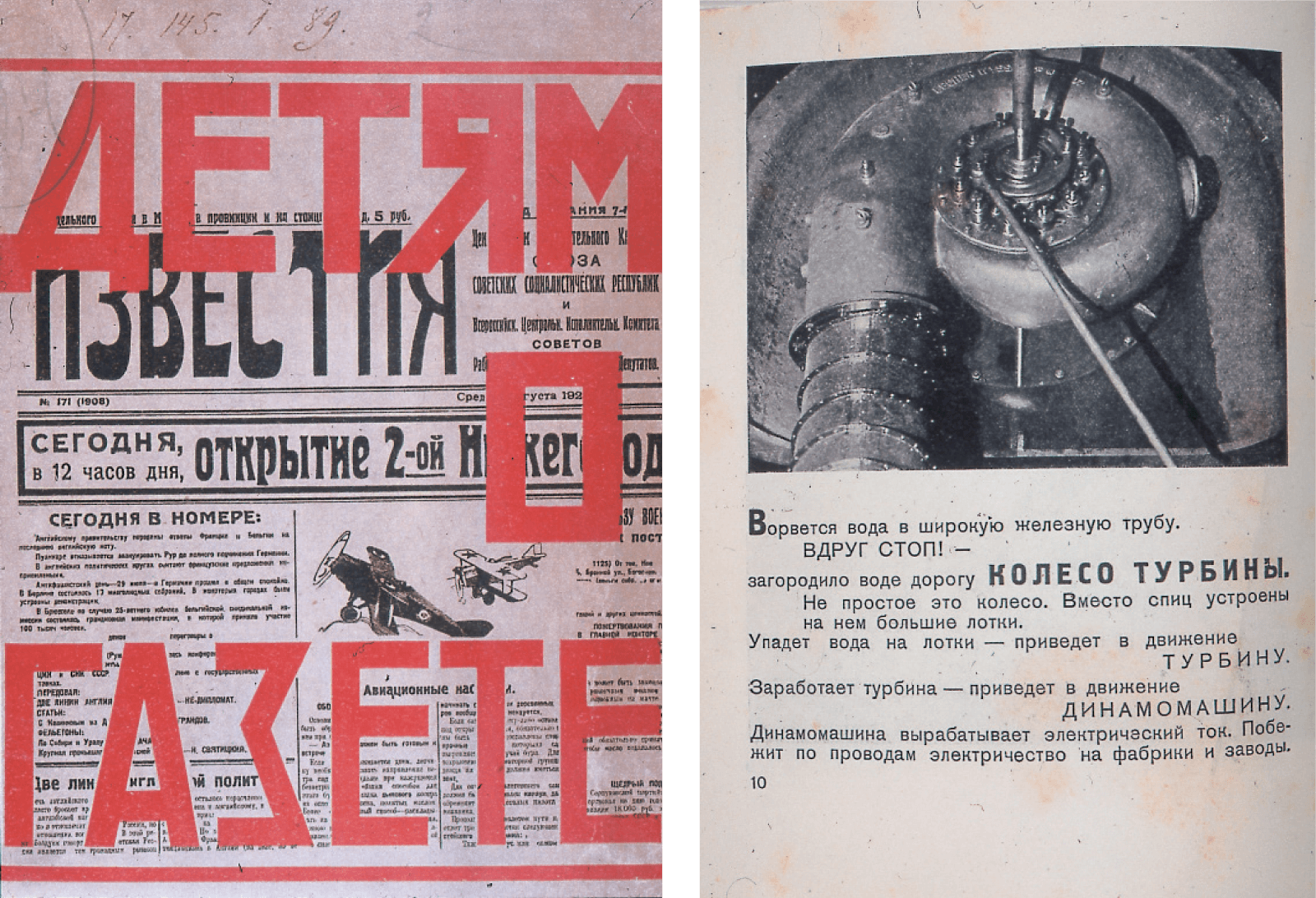

Another Smirnov-Chichagova book, The Newspaper Explained to Children, describes the process of newspaper production and features the front page of an actual issue of the Soviet newspaper, Izvestiia. The book’s illustrations, which are strongly reminiscent of Rodchenko’s advertising designs, adhere to the typographic principles developed by the Constructivists, employing a rigid geometrical organization, asymmetry, and sans serif lettering. Only one of its images features a specific individual rather than a generalized type—a photo-portrait of Leon Trotsky woven into the text that mentions his name.

The illustrations of Vladimir Lebedev, another Soviet artist who produced important children’s books related to technology, emphasized the two-dimensional nature of the page. In his 1927 illustrations for Samuil Marshak’s How the Plane Made the Plane, the artist reveals the structure of the plane’s parts: some of the instruments are depicted in cross-section to show their interior components and demonstrate their uses or processes. In the cover design, the topographical character is dominant to the exclusion of any decorative feature.

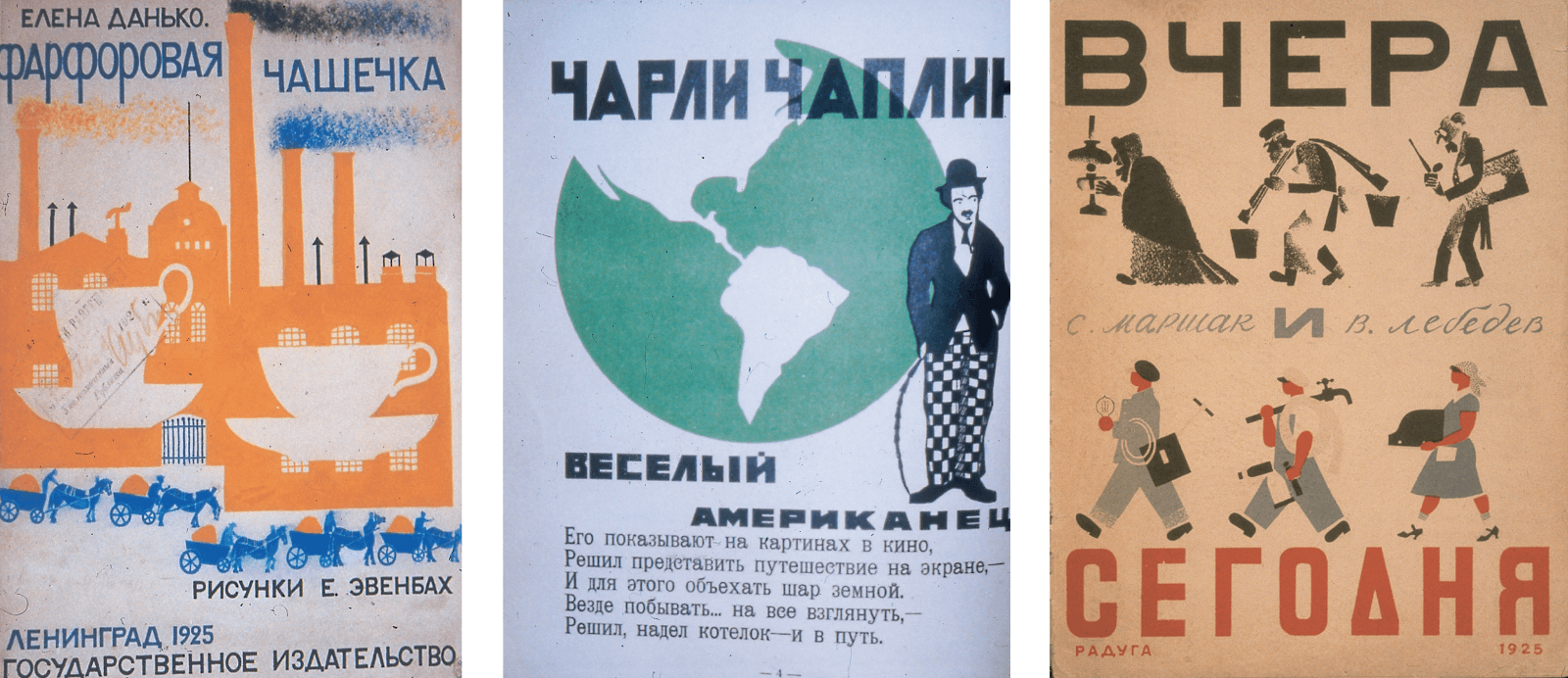

Yesterday and Today paradoxically uses the form of the fairytale to address the industrialization of Soviet society and the victory of progressive technology over traditional ways of life. Lebedev’s illustrations for the book promote modernization, featuring poetic images of the new objects that are produced by contemporary technology to replace the old ones.

Lebedev supervised a group of artists working at the Leningrad State Publishing House for Children (Detgiz) who completely changed the face of the new Soviet children’s book design. These artists included Evgenia Evenbakh, who based many of her illustrations on close observations of objects and production processes. When Evenbakh worked on a cover design for the 1926 book Market, she bought a pike at Leningrad’s Andreevsky market and made many sketches of it. In order to create her illustrations for the book Porcelain Cup, Evenbakh carefully studied the process of porcelain production at the Lomonosov Porcelain Factory in Leningrad. This type of intimate engagement was widely promoted during the later 1920s and 1930s, a time when many publishing houses organized business trips for their artists to industrial centers and collective farms. The artists Olga Deineko and Nikolai Troshin participated in these excursions, making the preliminary drawings for their production books directly at the factories they visited. Deineko and Troshin’s books informed young readers about metric units or explained where their cotton clothes, bread, shoes, and sugar originated.

Soviet children’s book illustrators commonly employed found photographs as figurative elements, often utilizing the avant-garde technique of photomontage. For his illustrations to Nikolai Mislavsky’s book, Dneprostroi, which demonstrated via short stories and numerous photos the ongoing construction of a hydroelectric station, Lantzetti appropriated various archives of press photographs.

The most successful production book for children about the First Five Year Plan was written by Mikhail Ilyin in 1931 and illustrated with photomontages by Mikhail Razulevich. This book, entitled Moscow Has a Plan, explained to its thirteen-year-old readers the processes of Soviet Socialist construction, representing the events described in the book through documentary photographs. Ilyin consistently compares the capitalist and socialist systems in favor of the latter. For example, one chapter of the book, entitled “Crazy Country,” criticizes the overproduction of food and consumer goods in the American economic system. A caption under a photograph depicting a pile of smashed cars reads: “Among this pile of used cars there are perfectly good ones. These used cars were bombed from an airplane so they would become totally unusable. It happened in Chicago, USA.” Those benefiting from burning the harvest, throwing out food, and destroying used cars are “Mr. Fox and Mr. Pox,” Ilyin’s fictional American capitalists. In contrast to these greedy, wasteful figures are the Soviet workers and peasants, who are pictured as happy individuals, proud of their active participation in the building of socialism. The latter’s portrayal is enhanced by Razulevich’s cover design, which depicts workers as towering, powerful figures seen from below in the manner of Rodchenko’s photographs. A whole generation of Soviet children received their introduction to socialist and capitalist economics by reading Ilyin’s book. The book was translated into English, Chinese, and Japanese, and published in over 20 countries. It caused somewhat of a stir in English left-wing circles.

Other important subjects of photo-illustrated children’s books of the 1930s were the struggle for the collectivization of Soviet agriculture, the protection of the harvest, and the Young Pioneers’ important role in the achievement of these goals; these themes are presented in P. Postyshev’s Patrols of the Harvest (1934). The book’s cover image contains a photo-portrait of a Young Pioneer intensely watching a collective farm field. The Pioneer’s facial expression exemplifies the political atmosphere at that time, with the constant search for “enemies of Soviet people.”

As early as 1927, the Committee of Children’s Literature prohibited the release of 81% of the children’s books by Raduga, the most experimental publishing house, since, according to the Soviet authorities, they were contaminated by harmful bourgeois ideology. In 1934, the First Congress of the Union of Soviet Writers in Moscow mandated Socialist Realism as the only acceptable artistic method for Soviet literature and art. For book design, this signified a return to traditional, non-experimental typography and design. In the following year the Communist Party issued a decree that placed all publishing houses specializing in children’s literature under the supervision of the Central Committee of the Komsomol (the Young Communist League), which established a system of strict censorship over children’s publications. The 1936 Pravda article, “About Artist-Doubters,” initiated a severe reaction against avant-garde experiments in children’s book design and forced them to employ more realistic and figurative styles.[8] That same year, an editorial in the Children’s Literature journal severely criticized Lebedev for his formalist approach: “Instead of concrete images of realistically rendered distinguished workers of the Soviet Union, Lebedev depicted schematic lifeless mannequins. In his drawings, the images of dull monsters have nothing in common with the most productive workers of the Soviet Union.”[9]

A previous version of this paper was presented at the Museum of Modern Art’s symposium “The Russian Avant-Garde Book, 1910–1934” on 30 March 2002.

- Sbornik dekretov i postanovlenii rabochego i krestianskogo pravitel’stva po narodnomu obrazovaniiu (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo APN, 1947), p. 156.

- L. Kormchy, “Zabytoe oruzhie,” (O detskoi knige), Pravda (Moscow), 17 February 1918, p. 3.

- E. V. Yanovskaya, Nuzhna li skazka proletarskomu rebenku? [Does a Proletarian Child Need a Fairytale?], (Kharkov: Knigospilka, 1925), p. 35.

- Ibid.

- G. Eikhler, “K voprosu o nauchno-tekhnicheskoi literature dlia detei,” Detskaia literatura (Moscow: Izdanie kritiko-bibliograficheskogo instituta), no. 3, 1935, pp. 1-3.

- Z. Dreizin, “Retsenziia: Otkuda posuda? N. Smirnov, G. Chichagova i O. Chichagova” in E. I. Stanchinskya and E.A. Flerina, eds, Iz opyta issledovatel’skoi raboty po detskoi knige (Moscow: Doshkol’nyi otdel Glavstsvosa, 1926), pp. 44-45.

- Anna Grinberg, “Knigi byvshie i knigi budushchie (dlia malen’kikh detei),” Pechat’ i revoliutsiia, nos. 5-6 (June–September, 1925), pp. 252-253.

- “O khudozhnikakh-pachkunakh,” Pravda, 1 March 1936; Quoted in Detskaia literatura (Moscow: Molodaia gvardiia), no. 3-4, 1936, pp. 40-42.

- Editorial, “Protiv formalizma i shtampa v illustratsiiakh k detskoi knige,” Detskaia literatura (Moscow: Molodaia gvardiia), no. 3-4, 1936, pp. 43-44.

Alla Rosenfeld, a native of Russia, is currently director of the Department of Russian Art and senior curator of Russian and Soviet nonconformist art at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. She is also a Ph.D. candidate at the Graduate Center, City University of New York.