Street Views

Urban photography and the politics of erasure

Kim Beil

City streets seemed eerily empty in the early years of photography. During minutes-long exposures, carriage traffic and even ambling pedestrians blurred into nonexistence. The only subjects that remained were those that stood still: buildings, trees, the road itself. In one famous image, a bootblack and his customer appear to be the lone survivors on a Parisian boulevard. When shorter exposure times were finally possible in the late 1850s, a British photographer marveled: “Views in distant and picturesque cities will not seem plague-stricken, by the deserted aspect of their streets and squares, but will appear alive with the busy throng of their motley populations.”[1]

During COVID-19 lockdowns, streets and squares truly were plague-stricken and empty. Drones buzzed over the avenues, vacant save for ambulances. Photographers stood in the middle of once-busy boulevards, taking glamour shots of the apocalypse. Although vaccines promise a return of street life, the future of urban photography may nevertheless continue to look more lockdown than lively; for several years, smartphone software engineers have been developing algorithmic methods to remove so-called “obstructions” or “distractions” from digital images, especially street scenes.[2] Automated editing features, such as the Samsung Galaxy’s “Eraser Mode,” can identify moving objects—passing cars, pigeons, pedestrians—that appear in slightly different positions across a burst of photos, and the user is then able to vanish them with a swipe. The language of automated editing makes this process seem natural, as if the real picture lay behind the thing that momentarily blocked the camera’s view. The balance between appropriate subjects and extraneous distractions is established by software designers years in advance and perhaps thousands of miles away.

Editing out distractions can be accomplished in two ways. The first, more common technique is called inpainting or infill, like the method used by Eraser Mode. Once a tedious manual process in Photoshop, recently it has become automated with the software’s Content-Aware Fill tool, which uses algorithms to identify similar patterns and textures to paste into edited areas of the image. When working from a single frame, the algorithm simply assumes that the hidden area is similar to its surroundings. The second method, which is not yet in wide use, borrows the concept of a “clean plate” frame from filmmaking. Cinematographers capture several seconds of an empty scene, keeping lighting and camera angle constant, but without the actors present. In the post-production phase, the clean plate is layered under the live action sequence, so that elements of the scene can be altered easily by deleting aspects of the top layer. Applying this technique to smartphone photography would necessitate a vast archive of clean plate frames, likely focusing on popular destinations.[3] Marc Levoy, a Stanford University professor emeritus who has worked on camera teams at Google Pixel and Adobe, envisions a time when distractions such as buses parked in front of the Eiffel Tower or trolley wires in San Francisco can be disappeared in the camera app, even before the photograph is taken.[4] Looking through the camera app would be like augmented reality. Many of these clean plate frames already exist, although they were not intended for this use. Google’s Photo Sphere (now part of Street View), for instance, invites users to upload and share their own images, recording every aspect of the public environment, from the streets to the seaside.

All pictures made with smartphones today employ some degree of computational enhancement. Jon McCormack, a vice president of software engineering at Apple, explains that iPhones take as many as nine photos to construct a single picture as it appears in the camera roll.[5] The software selects the best elements from each frame and collages them together, automatically and almost instantaneously. Whether we’re aware of it or not, the pictures we take are already influenced by what engineers think of as good pictures.

While computational methods may reposition the locus of control, shifting it from the photographer in the field to a set of rules written by software designers in a lab, earlier analogue photographers were not without outside influence. They learned their visual language from instruction books and magazines, as well as from other photographs, prints, and paintings. The changing aesthetics of photographs are not simply the result of technological progress. Despite the foundational legends of the plague-stricken square and the bare boulevard, empty streets aren’t just a technological effect. They are a cultural choice. Street views show us what and who is valued in images of the city.

• • •

Before people were dismissed as distractions, they were the desiderata of early photographers. The inability to capture even slow-moving objects was considered one of the new medium’s major shortcomings. In the first account of the Daguerreotype process to be printed in a US newspaper, Samuel F. B. Morse noted: “Objects moving are not impressed. The Boulevard, so constantly filled with a moving throng of pedestrians and carriages, was perfectly solitary, except an individual who was having his boots brushed.”[6] Another correspondent described the unsettling appearance of a horse with no head in one of the inventor’s demonstration images.[7]

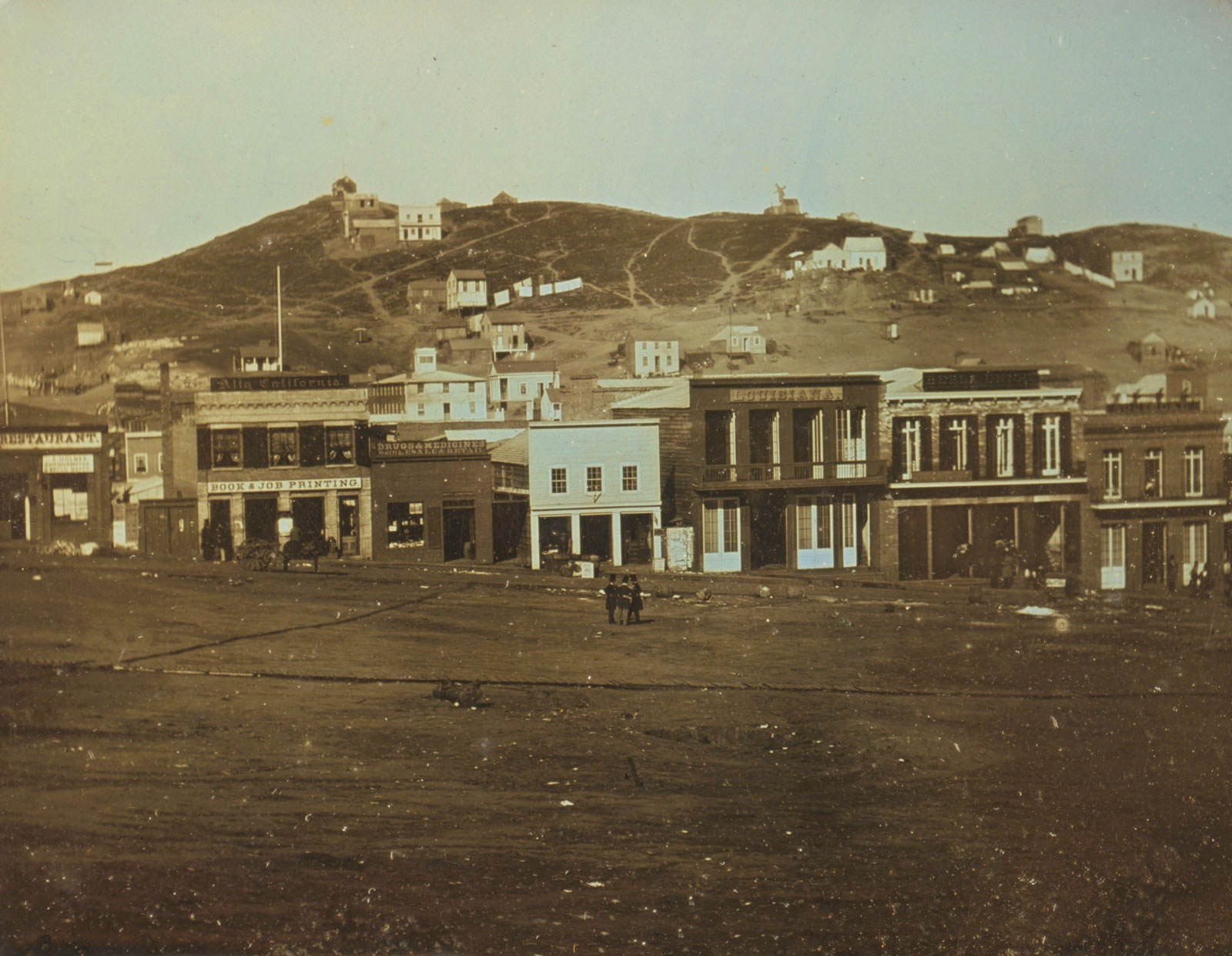

A decade later, street photographers were finding ways to adapt to the limitation. They posed people in front of buildings or showed them surveying vistas like staffage, the tiny figures who had long been used to provide variety and human interest in landscape paintings. An 1849 photograph shows a cast of San Francisco characters who seem to be standing guard outside a grocery store on Stockton Street, which may well have been necessary in the lawless Gold Rush city. In another early San Francisco photograph, three men in frock coats and tall top hats can be seen conferring in the city’s central Portsmouth Square amid the casual mess of abandoned barrels, gaping potholes, and a wooden plankway. A panorama made in the same period employs several of these illustrative figures, posed on a bluff overlooking the chaotic harbor. Behind them is a tangle of ships, abandoned by gold prospectors headed for the Sierra foothills.

These static sentinels of early city views were displaced at the end of the 1850s. City streets came to life thanks to improved chemistry and the use of smaller negative plates, which required less light for exposure. The new process was described as “instantaneous.” The physician and author Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. described one such view of Broadway in New York from 1859: “What a wonder it is, this snatch at the central life of a mighty city as it rushed by in all its multitudinous complexity of movement!”[8]

Holmes was especially taken with the detail of the view. He enumerated its elements in a particularly American kind of ekphrasis, imagining the future life of the photograph’s subjects as if they had been called to testify in a court of law: “The old woman would miss an apple from that pile which you see glistening on her stand. The young man whose back is to us could swear to the pattern of his shawl. The gentleman between two others will no doubt remember that he had a headache the next morning, after this walk he is taking.”[9]

Instantaneous views revealed life on city streets around the world in all its attitudes, from the rote to the raucous. In San Francisco, Lawrence & Houseworth, a pair of retired gold miners turned opticians joined the photographic trade. In their popular views published in the mid-1860s, the ghost-town aspect of San Francisco’s streets was replaced by the busy vérité of horse-drawn streetcars and crowded sidewalks.

A decade later, on 11 July 1877, the photographer Eadweard Muybridge climbed the city’s California Street hill to reach number 999, the site of Mark Hopkins’s mansion. The railroad tycoon’s observatory was then the city’s highest point. Muybridge created a seven-plate 360-degree view of the city in 1877. Opting for sharpness and extreme depth of focus, Muybridge closed his lens all the way down, which necessitated a long exposure. Although he would become famous for his instantaneous views of running horses, moving subjects faded from view in the panorama. More a city directory than an atlas, the descriptive key to the Muybridge panorama designates each site only with its owner’s name, mixing people such as Hopkins’s railroad company co-founders, Charles Crocker and Leland Stanford, with geographical features such as Mount Tamalpais and Alcatraz Island. The key culminates with label number 221: the turrets of the Hopkins mansion, where Muybridge stood to survey the city, which is captioned simply “Mark Hopkins.” In a masterstroke of metonymy, the ground on which the photographer stands to survey the city is Mark Hopkins himself.

Muybridge’s empty streets were part of an emerging tradition of “grand style” urban photography, according to the historian Peter B. Hales. Pictures of Gilded Age cities were lessons in interpretation. They pointed out the keys to civic life—and who held them. Elegant three-quarter views represent iconic architecture and imposing monuments from a generous distance. The boulevards and colonnades are as perfect—and often as empty—as in an architect’s drawing. Hales writes: “At its broadest interpretation, [urban photography] presented a set of urban values. Little coincidence, then, that the pictorial city was more awesome, more orderly, and more civilized than the reality.”[10]

The crowds rushed back into urban photography at the turn of the century. The rise of the photo-finishing industry and the release of the inexpensive Kodak Brownie camera opened up the practice to tens of thousands of new photographers. The company sold 150,000 Brownies in their first year on the market, more than the total number of cameras Kodak had sold in the previous decade.[11] Amateur photographers swarmed the streets, snapping pictures with their simple hand-held cameras. They recorded everything they saw, including each other.

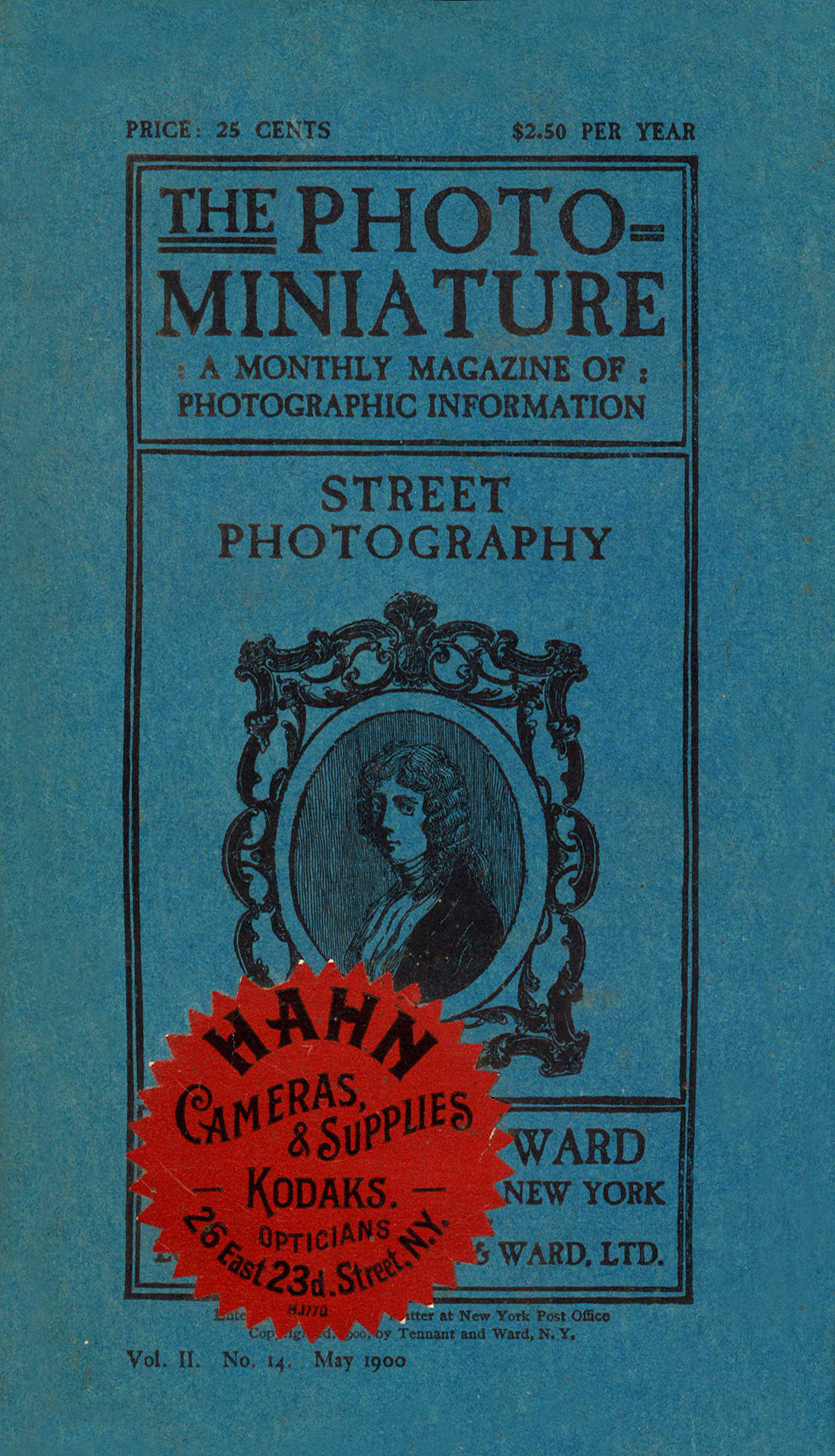

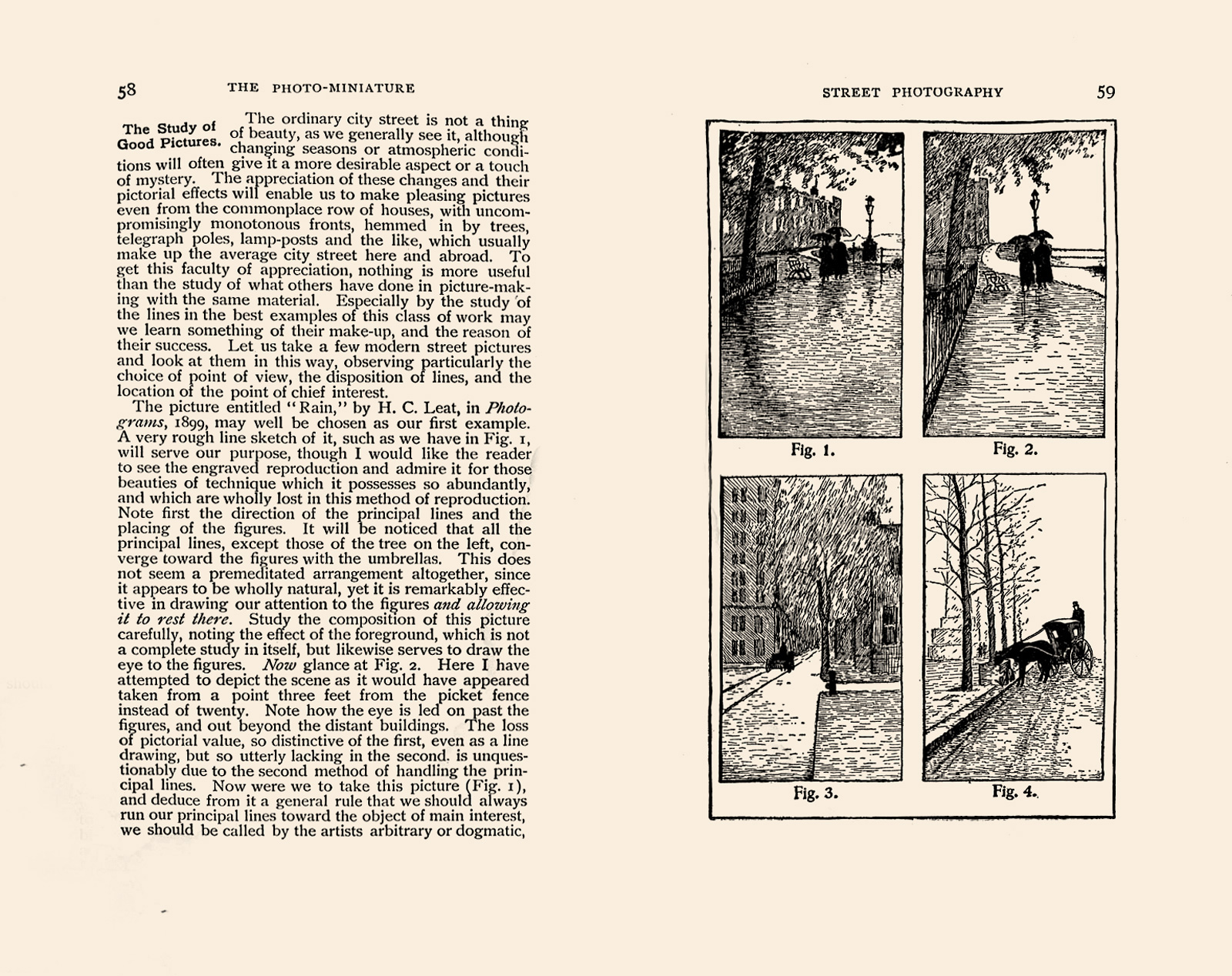

Dedicated columns in established newspapers, as well as scores of new how-to books and periodicals, were aimed at the exploding amateur market. Camera Craft magazine in San Francisco and The Photo-Miniature in New York were both founded in 1900 and featured street photography prominently in their early issues. The Photo-Miniature celebrated “the growing tendency in modern photography to depict the humor and pathos of life, as we see it in our city streets, rather than the beautiful in nature remote from man.”[12] Camera Craft advised amateurs to leave the grand-style architectural views to the professionals. Instead, amateurs should seek out “animated groups, children at play, street or wharf scenes, in fact any scene which may compose well and which might be turned into a picture.”[13] Good street photographs needed people, but they had to be properly placed. This wasn’t the total testimony favored by Holmes, but a vignette envisioned by the photographer.

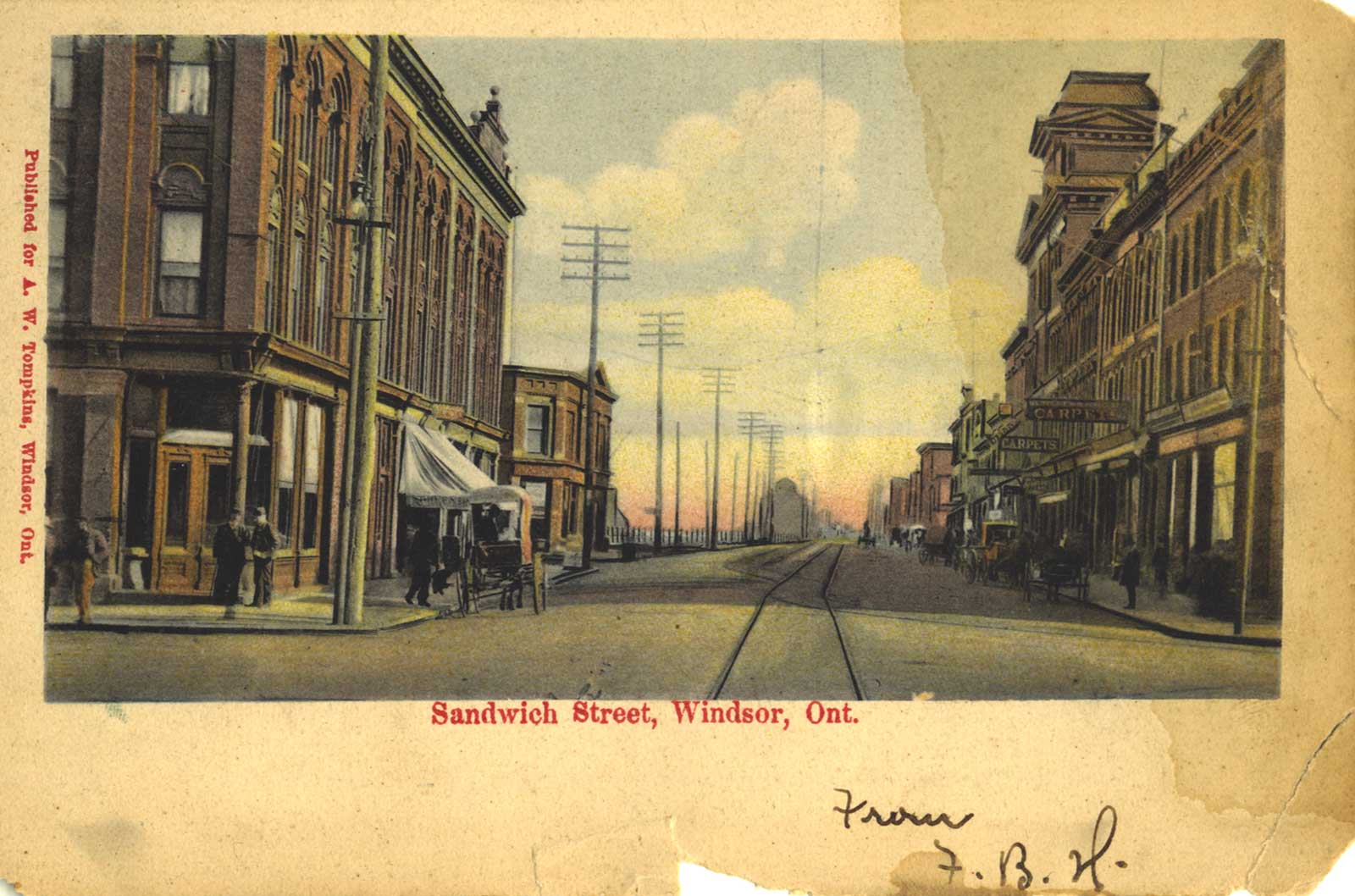

Amateur photographers could turn their hobby into a side hustle by selling their pictures as postcards. Sometimes these views were picked up by postcard publishers, colorized, and reproduced lithographically, but just as often they were printed locally or at home on specially formatted black-and-white photographic paper, called Real Photo Postcards. Some photographers may have attempted to follow the guidebooks’ advice on composition; many others simply captured the crowds as they swarmed the streets. Real, rushing people replaced the still staffage of the 1850s.

The American photographer Walker Evans grew up amid this surge in urban visual representation and became an avid collector of postcards. In 1962, he published an essay in Fortune magazine on postcards, titled “When Downtown Was a Beautiful Mess.” Illustrated with examples from his own collection, Evans wrote: “The very essence of quotidian U.S. city life got itself recorded, quite inadvertently, on the picture postcards of fifty years ago.”[14] Evans pointed to these images and their anonymous makers as the originators of his own photographic tradition, which he dubbed “lyric documentary.”

In a lecture at Yale two years later, also illustrated with postcards, Evans showed several early twentieth-century street photographs that might have been considered less than perfect in their day. He told the audience: “Now I feel that a picture of this sort has mood and authenticity, simple as it is, and also the time has lent it a poetry that obviously it didn’t have. The photographer probably wanted that wagon out of the way and now it makes the picture.”[15] What was considered a distraction in its day later stands as a testament to the realism of the image.

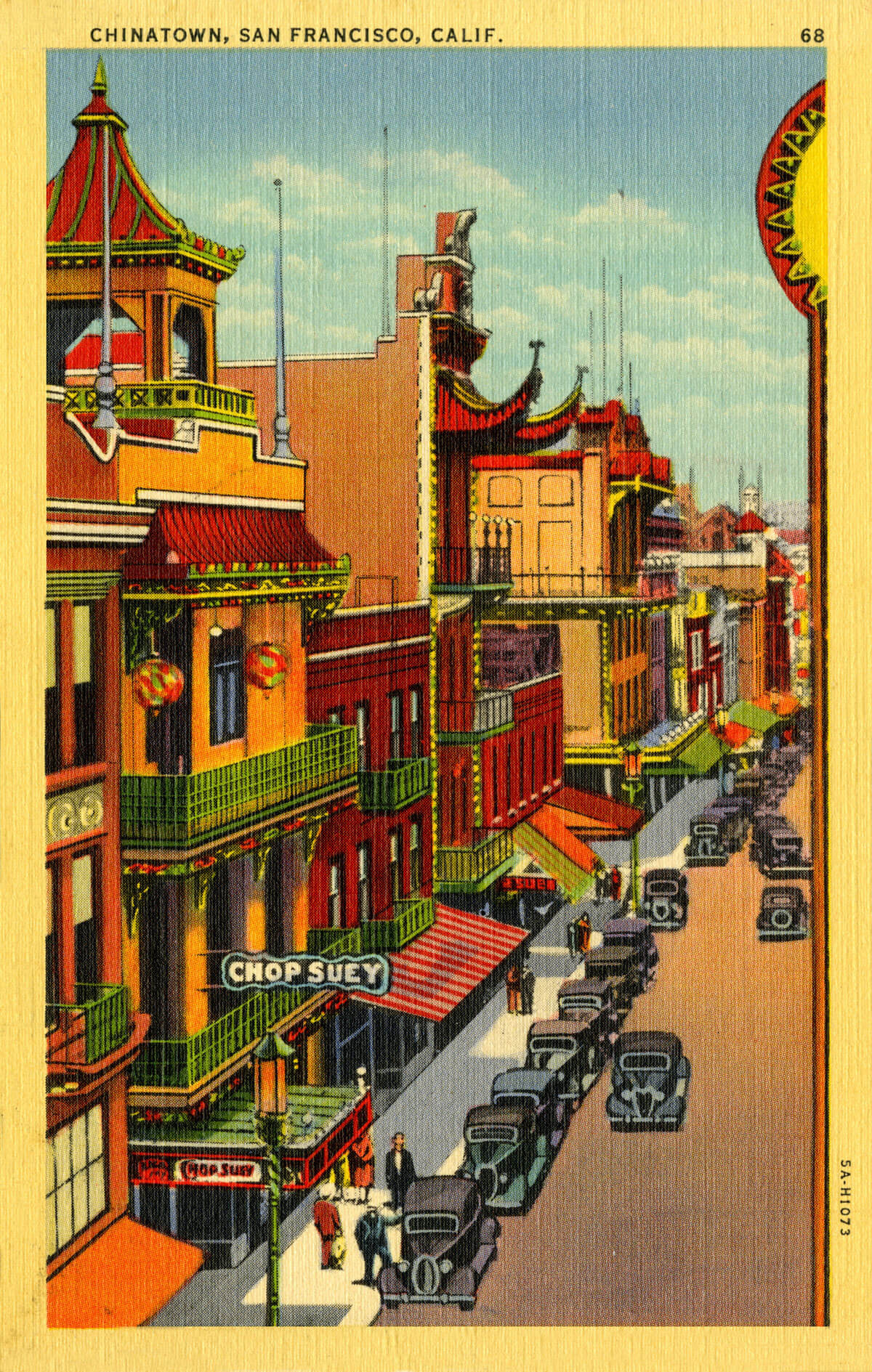

Evans wasn’t contrasting his busy street scenes with the empty streets of Gilded Age photography, but with midcentury postcard views from which the people had disappeared yet again. In 1931, a German-American printer named Curt Teich had developed postcards he called “linens,” which were printed on textured paper approximating the weave of fabric. Made using offset color lithography, Teich’s cards featured bold and varied colors, in contrast with the limited pastel palette of earlier cards. Linens also relied on heavy retouching. Artists corrected lens distortions, erased telephone and trolley wires, and even drew in airplanes, cars, or planned improvements to the street.[16] During the Depression, when crowds of people on the street often indicated breadlines or unemployment offices, linen postcards replaced lived reality with a vivid emptiness, interrupted only by regiments of identically rendered cars.

One hundred and eighty years after photography’s first street views, the avenues were again as empty as they had been in early pictures. The worldwide lockdowns of spring 2020 were seen by most people through photographic representations. Confined by stay-at-home orders, viewers were asked to believe in the realism of emptiness, which for more than a century had been only a trick of photography. Some cities, such as Rome, took advantage of the opportunity to record monuments that are typically surrounded by tourists.[17] In San Francisco, wild animals reclaimed the streets: coyotes and a mountain lion were the new travelers. City streets became their own clean plate frames.

In December of 2020, amid another wave of strict lockdowns, Google announced that Maps would allow user-submitted Street Views using a simple smartphone app. By this time, the trillion-dollar company had already recorded images of 10 million miles of streets and estimated that it covered 98% of the human-populated globe with more than 170 billion Street View photos. In a blog post, the company suggested that the goal of the new app was equity and access to the remaining two percent of the inhabited earth: “Your phone is now all you need to tell Google Maps what’s there—and let people around the world explore it through your lens.”[18]

When Google Street View was launched in 2007, virtual travelers could tilt down to see the car carrying the camera. In an update released the following year, the Street View car had vanished from view. Looking down revealed only the road. Since then, Street View aficionados have sought out glimpses of the cars’ shadows and occasional reflections in street-level windows. Like the turrets of Mark Hopkins’s mansion in the Muybridge panorama, these are the only moments when we see the invisible hand at work behind these corporate images of the city.

Google’s algorithms process the new user-submitted imagery just like official Street Views. They promise to blur faces and license plates. They monitor images and the people in them for obscenity, nudity, and crime. Given the choice, what kinds of photos will users submit: pictures that are empty of people or full of life? Elsewhere in Silicon Valley, software engineers have made the assumption that passers-by are distractions to be removed. But the empty, obstruction-free streets of computational photography are not new. They are bound up in the long history of economic control and the erasure of labor. The “grand style” urban photography of the late nineteenth century, for example, intentionally blurred out people on the street by using long exposures. In this lineage of image making, workers become anonymous or entirely invisible, and the products of their labor are swiftly and indelibly renamed for their employers—whether it is Mark Hopkins then or Mark Zuckerberg now, whose last name adorns San Francisco General Hospital.

Empty street views represent the ideals of industrial efficiency, a city that operates like a perpetual motion machine with little evidence of the workers that power it. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this meant immigrants, women, and child laborers hidden away in sweatshops, or Chinese railroad builders in the American West, who lived in separate encampments along the route and remained nameless in official accounts. Views made to celebrate modern, industrial cities hid workers in their places of employment, ignoring their hard lives outside work, just as their employers did. Pictures of laborers packed into tenement apartments or in the alleyways outside were classified as reform photography. This genre promised to show, in the words of photographer Jacob Riis, “How the Other Half Lives,” since they were invisible in city views that were underwritten by corporate interests.

More recently, this anti-labor ethos has denied full employment status to gig workers. California Proposition 22, a ballot measure heavily endorsed by Uber and Lyft, allows companies to classify their workers as independent contractors in order to avoid paying minimum wage and providing benefits.[19] Although ride-share drivers are ubiquitous on San Francisco’s streets, many can no longer afford to live in the city, where prices have soared due to rising demand from highly paid tech workers. These so-called “knowledge workers” are bused out of San Francisco every morning to tech campuses in Silicon Valley, while service sector workers commute into the city to serve them. By day, service workers deliver packages, clean homes, prepare food, care for children, walk dogs, and landscape yards. In the evenings and on the weekends, they serve food and drink, drive ride-share cars, and deliver still more packages. Empty street views erase this tide of people, one of the most visible symbols of the city’s economy.

The vacant street view also evokes the more recent experience of global contagion. Unhoused people and essential workers, who are disproportionately people of color in the Bay Area, were the only pedestrians on some major streets at the height of the lockdowns. Fetishizing the empty street, as many newspaper feature photos did, contributes to the erasure of these people from historical memory. Computational photography can, and will, be used to remove a variety of “distractions” from a scene. But as in earlier “grand style” urban photography, it is the visible indicators of labor, class, and ethnicity that are particularly at risk, because they make plain the unjust political reality of the city.

Google Photos promises that it’s “a safe home for your life’s memories,” yet the history of street photography suggests that these empty street scenes may be more like the dreams of nineteenth-century industrial titans than Walker Evans’s postcards, “those honest, direct, little pictures.”[20] Before selecting Eraser Mode or clicking delete, every photographer ought to think twice about who wields the power when pictures privilege empty streets. By editing out the lived reality of city streets, even amateur photographers contribute to a corporatized view of the urban environment, which favors free-flowing goods and capital while erasing the human cost that the information economy has exacted on cities like San Francisco.

- Lake Price, A Manual of Photographic Manipulation, Treating of the Practice of the Art; and Its Various Applications to Nature (London: John Churchill, 1858), pp. 161–162.

- Andrew MacQuarrie and Anthony Steed, “Object Removal in Panoramic Media,” in Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Visual Media Production (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015). Available at doi.org/10.1145/2824840.2824844. Antonio Criminisi, Patrick Perez, and Kentaro Toyama, “Object Removal by Exemplar-Based Inpainting,” in 2003 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2003: Proceedings. Available at doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2003.1211538. Han-Jen Hsu, Jhing-Fa Wang, and Shang-Chia Liao, “A Hybrid Algorithm with Artifact Detection Mechanism for Region Filling after Object Removal from a Digital Photograph,” IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 16, no. 6 (June 2007). Available at doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2007.896675. Tianfan Xue, Michael Rubinstein, Ce Liu, and William T. Freeman, “A Computational Approach for Obstruction-Free Photography,” ACM Transactions on Graphics, vol. 34, no. 4 (August 2015). Available at doi.org/10.1145/2766940.

- Though vast, the number of images required is not limitless because the user’s position need not be identical to the vantage point of the photograph being used as the clean plate; spatial discrepancies can be compensated for using the software’s warp and lens-distortion filters.

- Nilay Patel, “Marc Levoy on Moving from Google to Adobe and the Ethics of Computational Photography,” The Vergecast (podcast), 8 September 2020. Available at podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/marc-levoy-on-moving-from-google-to-adobe-ethics-computational/id430333725?i=1000490461345. What Levoy is describing is that the user will be able to choose when taking a photograph which objects the app should “disappear” and replace with the “neutral” background, but can also select in advance entire categories of obstructions that the app should always automatically disappear, such as fences or window-glass reflections.

- Matti Haapoja and Pete McKinnon, “Asking Apple Execs about iPhone Camera Secrets,” The Matti & Pete Show (podcast), 13 November 2020. Available at podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/ep14-asking-apple-execs-about-iphone-camera-secrets/id1462713591?i=1000498527498.

- Samuel F. B. Morse, “The Daguerrotipe,” New-York Observer, 20 April 1839.

- Richard Harlan, “Letter from Dr. Harlan,” Medical Examiner: Devoted to Medicine, Surgery, and the Collateral Sciences, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: n.p., 1839), p. 377.

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Soundings from the Atlantic (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1864), p. 182.

- Ibid.

- Peter B. Hales, Silver Cities: Photographing American Urbanization, 1839–1939 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), p. 132.

- Todd Gustavson, Camera: A History of Photography from Daguerreotype to Digital (New York: Fall River Press, 2009), p. 143.

- Osborne I. Yellott, “Street Photography,” The Photo-Miniature, vol. 2, no. 14 (May 1900), p. 50.

- “Print Albums or Print Scrap-Books,” Camera Craft, vol. 8, no. 5 (April 1904), p. 214.

- Walker Evans quoted in Jeff Rosenheim, Walker Evans and the Picture Postcard (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2009), p. 46.

- Ibid., p. 111.

- Jeffrey L. Meikle, Postcard America: Curt Teich and the Imaging of a Nation, 1931–1950 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015), pp. 306–307.

- Johannes Röll et al., “Rome and Naples in Spring 2020,” Bibliotheca Hertziana: Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte, 1 February 2021. Available at galerie.biblhertz.it/en/lockdown.

- Stafford Marquardt, “Now Anyone Can Share Their World with Street View,” The Keyword (blog), Google, 3 December 2020. Available at blog.google/products/maps/anyone-can-share-their-world-with-street-view.

- In August 2021, a superior court judge in Alameda County deemed the measure unconstitutional and unenforceable, but Uber and others say they will appeal the ruling, which according to California law means that the proposition will stay in effect until the appeal is adjudicated. Proposition 22’s advocates have already spent more than $200 million on the measure, making it the most expensive in the state’s history.

- Jeff Rosenheim, Walker Evans and the Picture Postcard, p. 14. The Google Photos quotation can be found at google.com/photos.

Kim Beil lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and teaches art history at Stanford University. She has written about art and visual culture for The Atlantic, The Believer, and Lapham’s Quarterly, among other publications. Her book, Good Pictures: A History of Popular Photography (Stanford University Press, 2020), tracks fifty stylistic trends in the medium from the nineteenth century until today.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.