Wherever We Are Gathered

The Black Arts School and its afterlives

Joshua Bennett

This text is part of “Imagination and the Carceral State,” a series of essays organized by Joshua Bennett for Cabinet’s Kiosk platform. For his introduction to the portfolio, see here. The other texts in the series include “No Man’s Land” by Elleza Kelley, “Abolitionist Alternatives” by Che Gossett, and “Myth Lessons” by Matthew Spellberg.

I’ve come to understand what people in power have long known—education can be used both to oppress and to liberate. Ideas are indeed powerful things. I further came to understand that America’s colonization of Blacks employed the textbook as often as the bullet.

—William H. Watkins

I had proposed that the task of Black Studies, together with those of all the other New Studies that had also entered academia in the wake of the 1960s uprisings, should be that of rewriting knowledge.

—Sylvia Wynter

My wife and I recently welcomed a baby boy. My days are thus filled with impossible figures, vexed remembrances. I think of my nephew, Miles, told at nine years old that his now hip-length locs were a distraction; that he made his teachers, most of them white, feel threatened, incompetent, small. I think of myself in 1993, almost his age, overhearing a kindergarten teacher telling my parents that I would never function in a classroom. The stories, the data sets, are more than familiar. I keep the relevant charts and graphs at hand. I know their truth in a place where no one can steal it. I hear a colleague from Princeton mention a Pan-African homeschool that meets via Zoom; boys and girls across the country greeting one another each morning, a new collectivity born in the midst of converging pandemics—both COVID-19 and global anti-Blackness, that age-old ecological catastrophe. In quiet moments, I envision the invincible beauty of this gathering. I feel the strength of everything the world can’t take away anyway come back to me. In a flash, it is as the old saints say: I feel like going on. My dreams drift to other such social experiments throughout the history of Black people in the Americas. I was raised uptown, so Harlem, naturally, is the first place that comes to mind; 125th street and all that we built there, however briefly. How this too has been my son’s inheritance since the day he arrived. A legacy of freedom struggle and indomitable splendor, unfettered dreaming in the face of brutality beyond measure. And a love that makes such living, such abiding courage at the edge of life itself, worthwhile.

At its very core after all, Black Art—as Jones and his comrades defined it—demands that we remember. Over and against the myriad temptations of an implicitly presentist US American cultural milieu, the vision of Black Arts embodied in this moment of marching is a call back to a much longer tradition: one of Black marshals and majors and bearers of banners of nations that live only in the freedom dreams of the marginalized. The flags of nations that have never existed and are yet to come. A captive nation within a nation.[1] Or, a Nation on no map, if you prefer Gwendolyn Brooks’s approach.[2] Or the America Langston Hughes calls into being in the fourteenth stanza of his classic poem, “Let America Be America Again”: The land that has never been yet—And yet must be.[3]

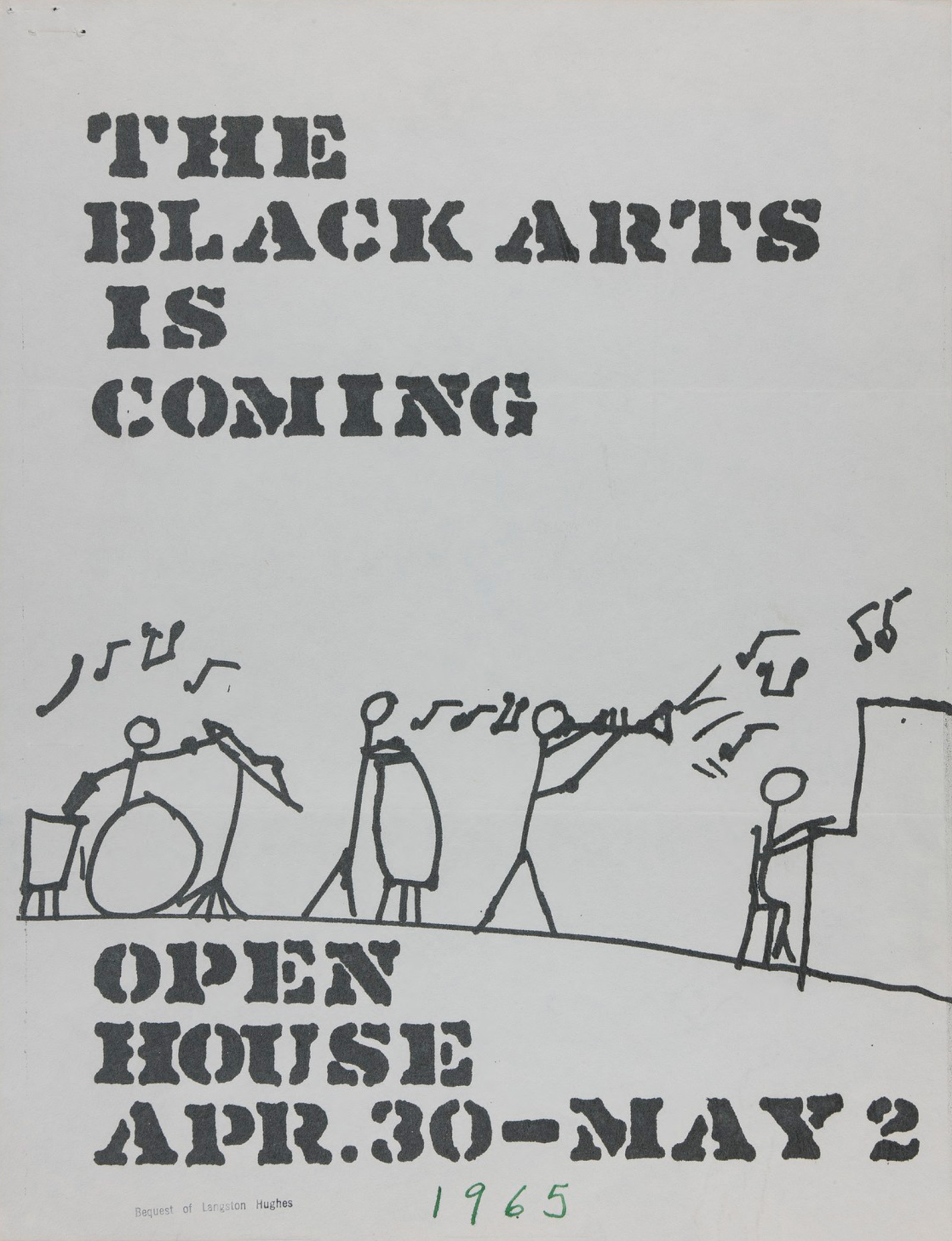

Although BARTS existed for only a year, it had a meaningful impact on the arts landscape of its day. In this sense, it stands as a historical monument to what I would like to imagine here as a kind of Black temporality. Black life as measured not in minutes but moments, Black social life itself an everyday, ongoing set of practices and protocols rooted in the fact that we all ultimately lose what we love, and thus must embrace loss and love not as antipodal, irreconcilable forces, but as irreducibly bound up with one another, entangled as the individual obsidian coils of a baby cousin’s braid, or the internal wiring of a microphone on a makeshift stage from which that child will recite an ode to their neighborhood corner—Lenox or Nostrand or King’s Boulevard—at the very top of their dark and holy voice, as if it were the most urgent news any listening audience could imagine, or else a trumpet to signal the end of the present world and the arrival of another. BARTS comes to us in the present, then, not as an institutional failure in any traditional sense, but instead as an unbound, unbroken meditation on how we might plan outside of the easy binary of success and failure in any terms we might easily recognize within our present order, constrained as it is by the sort of cruel optimism, pace Lauren Berlant, that warps our ability to see the successful school as one in which the children play, grow, learn on and in their own terms.[4] BARTS attracted artists such as Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, and Sonia Sanchez as teachers, and ultimately left an impact in the collective imaginations of both the young people of Harlem whom it immediately served and countless other programs throughout the country.

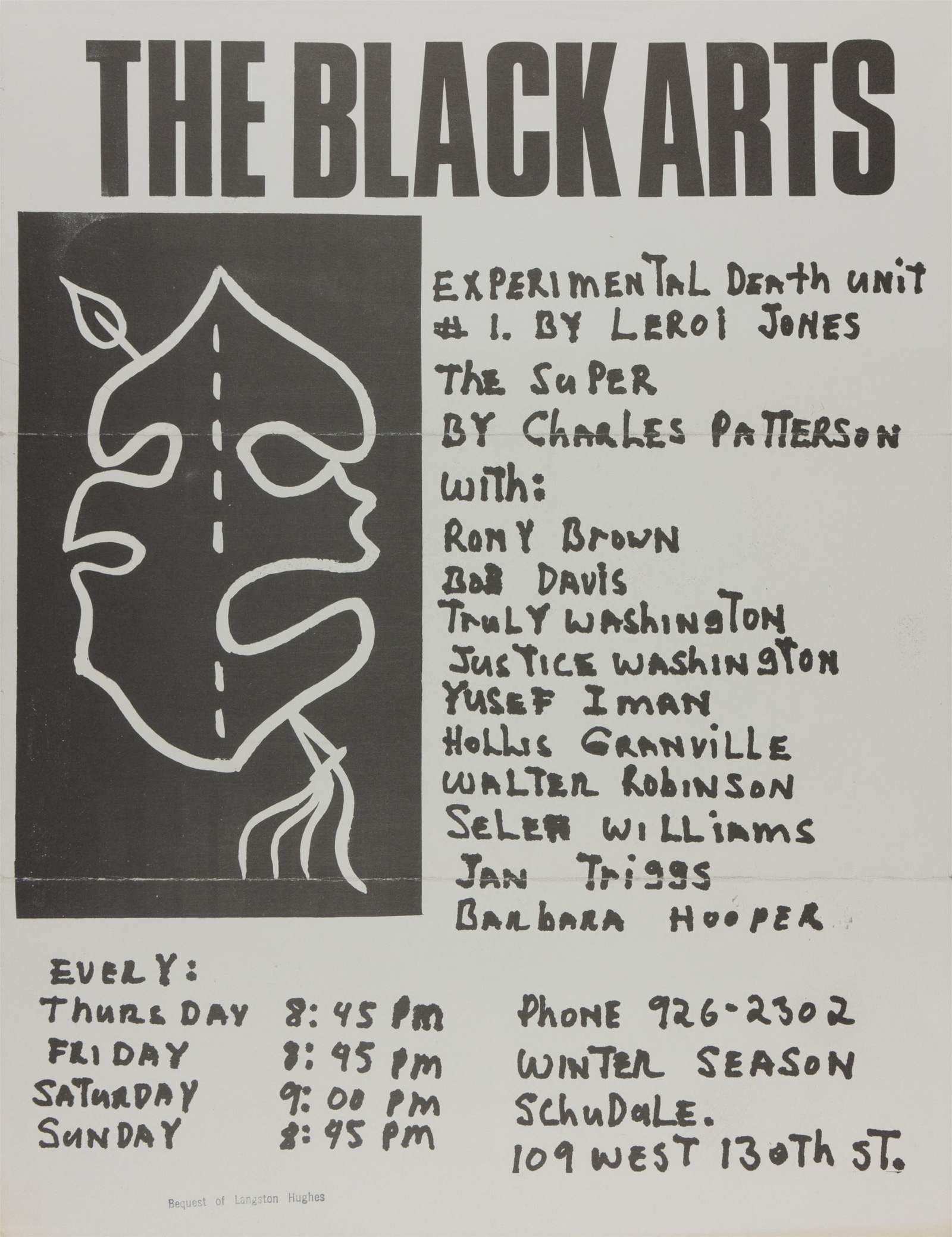

The man holding the left side of the flag is LeRoi Jones. Today, he is wearing sunglasses and a jacket made of military canvas. The flag reads The Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School. A small procession follows the flag and the men who hold its body as it is carried toward West 130th Street. What does this particular flag make possible? What does it gesture toward or concretize? The symbol on the front of the banner is blurred into obscurity, though we know from archival sources that it is a pair of masks meant to stand in for the dramatic arts: one representing comedy, the other tragedy. Seen at a distance, through the cloud of possibilities that this blurring makes available, one can imagine the silhouette of a student, a pirate, a warrior, some rebel or outlaw figure behind each mask, a fugitive with his mind on a different world. The literate slave as the fugitive slave.[5] The acquisition of knowledge as the means through which one might steal (themselves) away.

In addition to core classes in acting and poetry, BARTS also offered courses with titles such as Business Machines, Clerical Job Training, Cultural Philosophy, Dance, Cinema, Music, Political Science, Psychology of Migration, and Social History of the West. Spanning an entire range of methods and disciplinary formations, the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School course catalogue makes clear, in one sense, that Jones’s vision of what comprised a sound anti-colonial education was quite unorthodox. The BARTS curriculum also included a course in Remedial Reading and Mathematics, an entry which, to my mind, clarifies more completely the stakes and aims of the school itself. The goal was not solely to train a cadre of revolutionary artists, but to prepare a generation of young people with every instrument they might need to flourish in an anti-Black world. The aim was a robust liberal arts education with an emphasis on the unheralded peoples of the planet Earth, and the cultivation of not only what Jones then termed “socially responsible” citizens of “the ghetto,” but of Black people everywhere. Jones’s revolutionary vision was one in which the seemingly permanent Black American underclass would find both the necessary psychic instruments to sustain themselves against white supremacist ideology and the everyday skills needed to feed themselves. The school’s broader purpose was essentially inextricable from that of the Black Arts Movement: to encourage a socially relevant set of Black aesthetics that would further build up the global struggle against anti-Black ideology. The theater and school passionately advocated for African diasporic art in all its myriad forms, with dance recitals, poetry readings, visual art shows, and new dramas created by the instructors.

The troupe brought the theater arts into the local community through a number of divergent means, including a vehicle that Jones famously dubbed the Jazzmobile. Instructors from the school would drive the Jazzmobile up and down 130th Street, often enlisting Black youths from the neighborhood to serve as library assistants, teaching assistants, stagehands, and maintenance workers. These young people would eventually teach these crafts to children even younger than they were, creating, in their own way, a tradition within a tradition, a legacy of apprenticeship and childhood collaboration that would remain, no matter the fate of any individual building or community institution. BARTS also brought the theater to the community by putting up improvised stages in playgrounds, parks, in empty parking lots, and on street corners. Anywhere the people were gathered, they showed up and showed out.

Funding from Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited, a local social activism organization in turn funded by the US government’s Office of Economic Opportunity, provided much of BARTS’s support early on. In the end, having so much of their financing tied to this single source would help contribute to the school’s tragic demise. BARTS was founded with the help of a $40,000 antipoverty grant, and eventually, following a concerted disinformation campaign by a network of concerned white citizens in varied positions of social and political power, controversy erupted over such a flagrantly anti-American—at least in the minds of the school’s detractors—use of public funds. In his autobiography, Jones remembers the problem beginning when he denied Sargent Shriver, the head of the Office of Economic Opportunity, entry into the BARTS building while school was in session. On 30 November 1965, an Associated Press release accused the group of anti-white racism, claiming that its productions supported secession and portrayed the general white American populace in a negative light. Several other published articles claimed that BARTS employed members of “Black terrorist groups” such as the Five Percenters, going so far as to cite the theology of the sect at length in print. The public outcry culminated in an armed police raid on the brownstone building that resulted in several arrests and reportedly uncovered firearms, drugs, bomb materials, and an underground gun range. A number of representatives from Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited and other antipoverty programs defended the school’s activities, going so far as to argue that young people in danger of criminal involvement were, in actuality, the very individuals the programs were intended to help. Despite these efforts, public funding all but disappeared. This absence of cash on hand, coupled with a number of internal disputes among the faculty and the exit of Jones, saw the collapse of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School around that same time.

Or, at least, this is the most familiar rendition of the story. But what if there were another rendition of the BARTS creation myth available to us, calling out from the gaps in the historical record? What version of this tale lives on in the darkness? In spaces unattended to or altogether obscured from view? It is my sense that the most compelling, complete versions of this tragedy have yet to be told. Ones that can only be approached by reassembling the fragments and shards left in the wake of the school’s untimely implosion. Such a project is beyond the scope of the present essay. But one such fragment deserves at least a preliminary look for everything it might potentially reveal about the rise and fall of BARTS: the organization’s FBI file.

The affective through-line of the FBI files—though the tone is, unsurprisingly, rather muted throughout—is one of both requisite suspicion and genuine surprise. Various out-of-context BARTS pamphlet passages on the teaching of Black Art as a mystical practice, for example, are no doubt meant to signal for readers at the bureau the sense that they are dealing not with any revolutionary sect in the way they have been trained to understand such a term, but an organization whose central principles are countercultural along an entirely different vector. Page after page, agents describe in great detail an organization energized primarily by its radical pedagogy and loving relationship to Harlem, but always existing at the precipice of destruction given its relationship to financial support from outside the neighborhood. Though their aim—as stated clearly by both Black writers of the time and later scholars such as William J. Maxwell—was to upend the organization, and not merely monitor or oversee it, aspects of the file tell a story marked not just by internal struggle but also by dazzling flashes of pedagogical breakthrough.

This atmosphere of surveillance—the sense that the window of opportunity for this particular revolutionary project was closing for the students and teachers involved, or else would actively, forcefully, be closed for them before long—was no doubt a contributing factor in the collapse of the school. But there were a number of other elements as well, not the least of which was a clash between Baraka, Harold Cruse, and a host of newcomers around how best to guide the institution into the future. In Cruse’s own words, the school was taken over by a group who “destroyed [it] from the inside” and eventually “forced out everyone else who would not agree with their mystique.”[8]

In the present, we would do well to continue the study of the life cycles of revolutionary projects like BARTS. Such study might yield important lessons for arts spaces and organizations that have likewise set their sights on the transformation of the present milieu through the cultivation of revolutionary ideas, and the empowerment, through the singular power of performance, of the narratively condemned peoples all over the globe. In this sense, the institutional history of BARTS serves as powerful historical example and cautionary tale. Especially for those who likewise imagine Black poetics, Black Art, as a kind of collective incantation, a poetics and a praxis made to the measure of the world.[9]

- James Baldwin, “How to Cool It,” Esquire, vol. 70, no. 1 (July 1968). Available at www.esquire.com/news-politics/a23960/james-baldwin-cool-it.

- Gwendolyn Brooks, “The Blackstone Rangers,” in The Essential Gwendolyn Brooks, ed. Elizabeth Alexander (New York: The Library of America, 2005), p. 94.

- Langston Hughes, “Let America Be America Again,” in The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, ed. Arnold Rampersad (New York: Vintage Classics, 1995), p. 191.

- See Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

- For more on this figuration, see Jarvis Givens’s forthcoming book Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021).

- This idea of the “American School” is elaborated by Givens in his forthcoming book, Fugitive Pedagogy.

- See Carter G. Woodson, The Mis-Education of the Negro (San Diego, CA: The Book Tree, 2006), p. 3.

- Harold Cruse, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual: From Its Origins to Its Present (New York: William Morrow, 1967), p. 440.

- I am borrowing this final phrase from Aimé Césaire, who wrote: “At the very time when it most often mouths the word, the West has never been further from being able to live a true humanism—a humanism made to the measure of the world.” See Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001), p. 73.

Joshua Bennett is the Mellon Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Dartmouth College. He is the author of three books of poetry and criticism: The Sobbing School (Penguin Books, 2016)—winner of the National Poetry Series and a finalist for an NAACP Image Award—Being Property Once Myself (Harvard University Press, 2020), and Owed (Penguin Books, 2020). Bennett earned his PhD in English from Princeton University, and an MA in Theatre and Performance Studies from the University of Warwick, where he was a Marshall Scholar.

Bennett has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Ford Foundation, MIT, and the Society of Fellows at Harvard University. His first work of narrative nonfiction, Spoken Word: A Cultural History, is forthcoming from Knopf.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.