Telling Stories

The entangled narrators of true crime

Lukas Cox

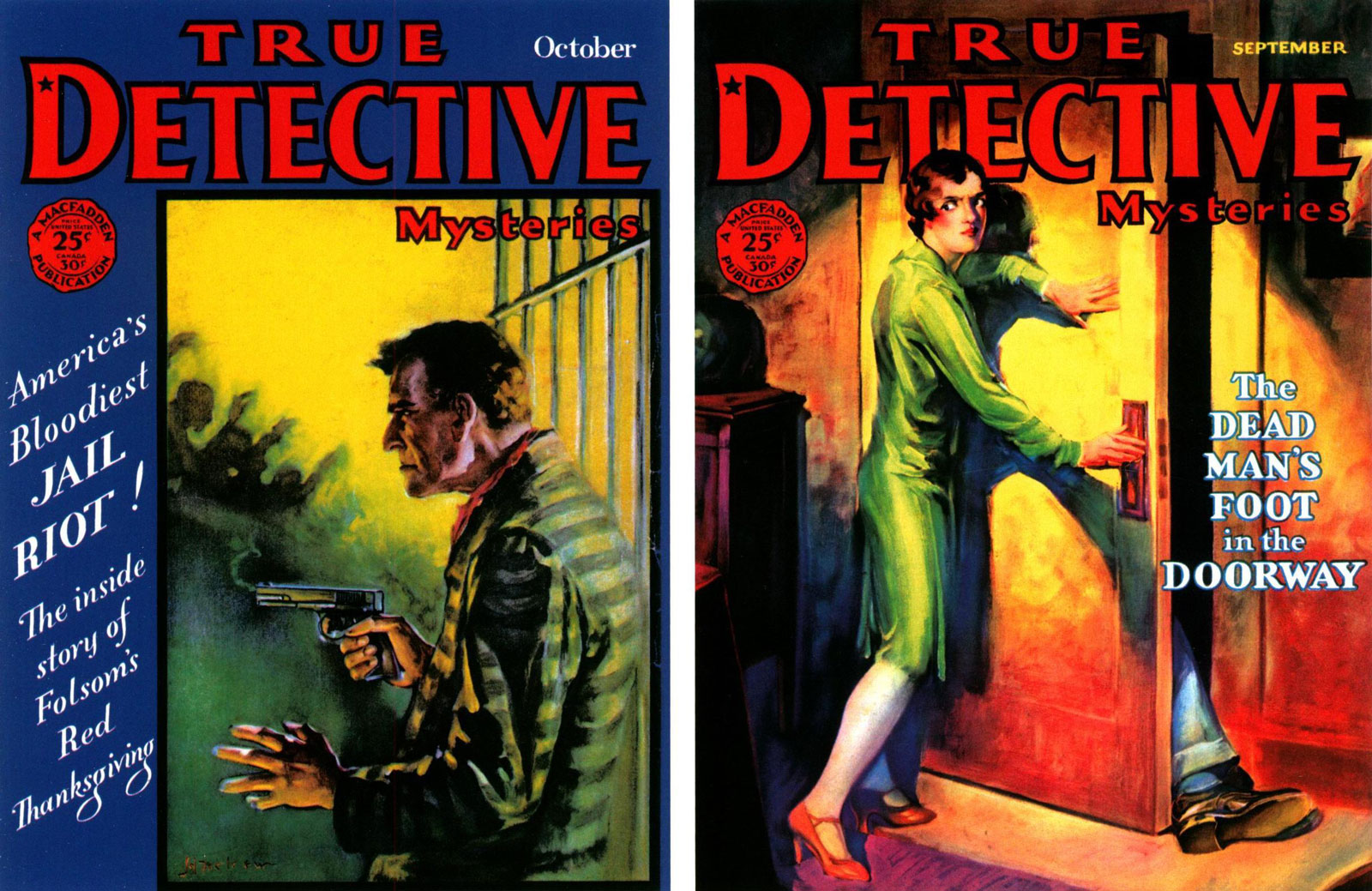

In the late summer of 1941, a young woman identified by the initials J. B. wrote to the editor of the wildly popular crime magazine True Detective with a story about her father. “Whenever Dad came home from work,” she begins, “he usually found me huddled in a chair reading a mystery magazine.”[1] Her father does not approve. To him, the stories in the magazine—lurid and sensational tales of real murder cases, complete with vibrant illustrations of partially clothed women—are “just trash.” One night, her father calls for something; captivated by the story in her hands, she doesn’t hear him. “Suddenly he was standing before me, tearing the magazine from my hands as he raved, ‘I’m tired of your reading this trash—let me see this!’ He looked through the magazine and finally glanced up: ‘Hmmm, this really has something.’ That was the last I saw of the magazine, for Dad read it through.” He can’t help it: the stories are too entertaining, too engrossing, too real. In a flourish sure to pique the interest of the magazine’s marketing staff, the anonymous writer finally identifies the publication in question: “Yes, you guessed it. It was True Detective.”

However apocryphal her letter may be, J. B. has her finger on the pulse of the troubling matrix of questions, repulsions, and curiosities that still swirl around the true crime genre in the twenty-first century. True crime stories thrive at the interstices of journalism and tabloid, horror and mystery, the newspaper and the novel. Some may, as J. B.’s draconian father presumes, revel in the melodramatic spectacle of car chases and spattered blood. Others, like Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, win the Pulitzer. Should we feel bad reading, watching, and listening to these stories? Or thrilled? And above all, why are we—and our fathers, mothers, brothers, and sisters—perpetually unable to put them down?

In an attempt to resolve these questions, critics and commentators have gravitated toward one overriding theory of readership. At the heart of this theory is the contention that, given the simultaneous brutality and reality of the criminal activity it describes, true crime literature must instill in us an unusually visceral identification with its characters. Two camps have formed regarding the locus of this identification: some claim that we identify with the criminal, while others insist we identify with the victim. Sympathetic identification with a murderer, for its part, suggests a macabre fascination with the “evil mind,” a fixation on the gory details and logistical vagaries of killing, and perhaps the morbid understanding that violent tendencies similarly lie “within” each of us. Identification with murder victims, by contrast, mobilizes a safer, more sanguine formulation of human psychology in which true crime stories become how-to guides, riveting lessons on how to avoid becoming victims ourselves.

The first of these two arguments has become a notably common explanation in critical circles. David Schmid, for example, argues that “there is something intrinsic in true-crime narratives that generates sympathy for the criminal,” given that literature of the genre is “always about the criminal in a way that it is not about the victim.”[2] Karen Haltunnen carries the thesis further, delineating a path between identification and a form of implication: “if the killer is so deeply alien to us,” she asks, “why must we repeatedly imagine ourselves walking in his footsteps, accompanying him to the crime, witnessing his murderous violence, revisiting the scene, examining his weapons, gazing upon his victim?”[3] This is a line of questioning steeped in Schadenfreude and voyeurism, compelling in its affirmation of a universal obsession with death and violence. Indeed, for Schmid and Haltunnen, these are deeply human instincts; true crime merely allows us to revel in them.[4]

The second strand of thought, which hypothesizes that we instead identify with the victim, is equally popular. In a recent piece for the New York Times, for example, Kate Tuttle attempts to explain statistical evidence that true crime readership is overwhelmingly female by granting the genre a powerful didactic effect. “Perhaps our fascination with these stories stems in part from wanting to learn from them,” she reasons. “If a woman escaped her attacker in this particular way, we think, perhaps I could too.”[5] University of Richmond professor Laura Browder concurs: in her estimation, true crime narratives uncover “a secret map of the world, a how-to guide for personal survival,” especially for women.[6] Tuttle and Browder don’t deny the viscerally enthralling phenomenology of reading true crime—Tuttle notes that she herself “devoured” true crime books with pleasure; Browder acknowledges true crime’s “vicarious thrills”—but in both formulations the genre is, more importantly, instructive. The patriarchal world of true crime serves as a heightened manifestation of quotidian life—and its authors root their narratives in a foundational identification between female readers and female victims.

These theories are plausible, rational, and intuitive. But in their search for juicy psychological conclusions about the human psyche—and their rush to assume a direct line of identification between a story’s audience and its characters—they neglect to account for the critical force generating and focalizing our experience of the genre: the narrator. Narration in true crime stories is inherently active and often presented in first person, unmistakably molding our understanding of both the criminals and their victims in real time. In this way, true crime narrators are models of reading, more sources of mediation than identification—and they hold the key to understanding true crime’s undeniably hypnotic effects.

Take Serial, the hit podcast whose first season quickly amassed millions of devoted listeners and arguably launched our latest wave of infatuation for true crime. The first episode’s opening words, spoken by host Sarah Koenig, disclose a deeply personal journey: “For the last year, I’ve spent every working day trying to figure out where a high school kid was for an hour after school one day in 1999.”[7] The next twelve episodes function in much the same way—Koenig’s reevaluation of the murder of Hae Min Lee and the subsequent conviction of her ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed is driven, as a number of critics have already noted, by the meta-narrative of her own investigation, her uncomfortably close relationship with Syed and her deep-seated indecision about his guilt.[8] “My interest in the [case], honestly, has been you,” Koenig admits to Syed in one of their many phone conversations. “You’re a really nice guy. Like, I like talking to you, you know?” Syed abruptly responds—“You don’t even really know me, though, Koenig”—and Koenig is taken aback: “But wait, are you saying you don’t think that I know you at all?”[9] In these moments, which so frequently punctuate the show as to define it, Koenig deftly blurs the lines between narrator and character: she is an investigator at work, admitting and embracing the messy strains of allegiance and subjectivity that govern her investigation. Along the way she makes mistakes, often pursues the wrong avenues, and litters her narration with the unmistakable inflections of casual conversation (“like,” “you know,” “I mean”). This captivating portrayal of ambivalence continues through Koenig’s final declaration in the season finale: “I don’t believe any of us can say what really happened to Hae. As a juror I vote to acquit Adnan Syed … [but] if you ask me to swear that Adnan Syed is innocent, I couldn’t do it. I nurse doubt. I don’t like that I do, but I do.”[10] Season one famously ends with no conclusive answers, but it remains a compulsively bingeable paragon of true crime storytelling for admissions like these.

A similar narrative voice takes hold in the thrilling finale of HBO’s Emmy-winning 2015 documentary miniseries The Jinx. In the previous episode, the show’s director, Andrew Jarecki, and producers Marc Smerling and Zachary Stuart-Pontier uncover shattering new evidence implicating multimillionaire Robert Durst in the 2000 murder of his friend Susan Berman. The season finale provides an engrossing behind-the-scenes look at the filmmakers as they plan an encounter with Durst. “This is a guy,” Jarecki explains on camera, speaking of Durst, “who in some ways I’ve been giving tremendous benefit of the doubt … not just in terms of the kinds of questions I ask him, but in terms of my emotional connection to him. You know, I like the guy.”[11] He continues to borrow from Koenig’s playbook: “For years I’ve been saying to people, ‘I’m not afraid of him. I don’t feel fear.’ But at the same time you can’t help but consider that ... you’re potentially becoming the enemy.”[12] If Jarecki appears more acutely troubled about the personal stakes of becoming Durst’s “enemy,” of losing the close “emotional connection” the two once shared, than he is about the serious criminal implications of new evidence, this is no accident. Jarecki’s new role as a documentary subject, a character in front of the camera as well as behind it, betrays the formative investigative role he has played all along. There is no ethereal bond between viewer and criminal here; the dark and potentially psychopathic machinations of Durst’s mind remain frustratingly inaccessible. Instead, like Serial before it, The Jinx draws its power from its narrator’s tangible reckoning with his own disturbing involvement in the story, his ethical instability, his lack of journalistic objectivity. To understand Durst, we need Jarecki; without him, Durst is merely the subject of a tawdry news story.[13]

The recent influx of true crime podcasts and TV shows find their roots in a well-documented canon of print media—a canon unsurprisingly chock-full of strong narrators. Ann Rule’s nail-biting, best-selling debut The Stranger Beside Me (1980) tracks—what else?—her troubling personal relationship with Ted Bundy. “I have labored for a long time with my ambivalence about Ted,” she admits, just before advertising her enviable journalistic access: “Probably there is no other writer so privy to every facet of Ted’s story.”[14] Michelle McNamara’s 2018 book I’ll Be Gone in the Dark is an equally intimate first-person account, this time of a citizen investigator on an obsessive quest to uncover the identity of a murderer whose moniker she coined: the Golden State Killer. (Its opening words: “That summer I hunted the serial killer at night from my daughter’s playroom.”[15]) Truman Capote famously declared that he wrote In Cold Blood (1966) “without ever appearing myself,” but in his consistent and often manipulative penchant for planting clues, narrating dreams, and constructing wholly fictional scenes, Capote’s presence reverberates throughout.[16] The stories of True Detective maintain a similarly conspicuous editorial voice, shot through with extradiegetic entreaties to the reader—to seek and capture the fugitives its stories portray, to commend the valiant work of police officers and detectives, and above all to uphold the magazine’s strict law-and-order politics.[17]

In the world of crime fiction, of course, the entangled first-person narrator is nothing new. Twentieth-century hard-boiled novels are replete with detectives hampered by their wavering ethical commitments, broken relationships, and troubling pasts. But Koenig, Jarecki, and their fellow narrators are not hard-boiled detectives, and the crimes they investigate are not morality-soaked whodunnits conjured in the minds of Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler. Here the victims and killers are painfully real, the moral implications unavoidably murky, and the investigations governed less by the satisfying finality of a solved case than by a frustrating, seemingly inevitable sense of futility. (In Koenig’s world as in McNamara’s, questions merely lead to more questions; no conclusive declarations of guilt or innocence are revealed.) To be taken seriously, then, to operate and investigate in the same world, true crime narrators must appear just as real as their subjects. They must cop to their conflicts of interest, probe their own ambivalence about suspects, and sit with the uncomfortable reality that the crimes they investigate may never be solved. This performance of candid, self-reflexive narration is built into true crime, reifying the genre’s anomalous claim to truth. It is also, on a broader level, a natural byproduct of the genre’s hybridity: a crime reporter may state a fact, and a mystery novelist may make one up, but only at the queasy intersection of these two forms is a discursive formulation of authority required to reassert itself, constantly defining and redefining its own relationship to the story in question.[18] It is by this sleight of hand that true crime is allowed to have it all—the emplotment, suspense, and intrigue of fiction and the indelible immediacy of journalism—and because of it that the genre continues to thrive.

- True Detective, vol. 35, no. 5 (August 1941).

- David Schmid, Natural Born Celebrities: Serial Killers in American Culture (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006), p. 180.

- Karen Haltunnen, Murder Most Foul: The Killer and the American Gothic Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: 2000), p. 245.

- See also Jean Murley, The Rise of True Crime: Twentieth Century Murder and American Popular Culture (Westport, CT: Praeger), p. 160.

- Kate Tuttle, “Why Do Women Love True Crime,” The New York Times, 16 July 2019. Tuttle cites statistics presented in Amanda M. Vicary and R. Chris Fraley, “Captured by True Crime: Why Are Women Drawn to Tales of Rape, Murder, and Serial Killers?,” Social Psychological and Personality Science, vol. 1, no. 1 (Jan 2010). Available at researchgate.net/publication/240287787_Captured_by_True_Crime_Why_Are_Women_Drawn_to_Tales_of_Rape_Murder_and_Serial_Killers.

- Laura Browder, “Dystopian Romance: True Crime and the Female Reader,” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 39, no. 6 (December 2006), p. 929. Browder later notes that “true crimes allow women to gaze into the abyss—both of the terror suffered by crime victims and of their own traumatic memories—and to survive.”

- “The Alibi,” episode 1 in Serial: Season One (podcast), 2014. Produced by Ira Glass, Sarah Koenig, and Julie Snyder. Available at serialpodcast.org/season-one/1/the-alibi.

- See, for example, Ellen McCracken, “Introduction: The Unending Story,” in The Serial Podcast And Storytelling in the Digital Age, ed. Ellen McCracken (New York: Routledge, 2017). McCracken summarizes the argument of Jillian DeMair, whose contribution to the volume is “Sounds Authentic: The Acoustic Construction of Serial’s Storyworld.” DeMair rightly notes that this duality amounts to a recapitulation of the central argument in Todorov’s 1966 essay “The Typology of Detective Fiction.”

- “The Case Against Adnan Syed,” episode 6 in Serial: Season One. Available at serialpodcast.org/season-one/6/the-case-against-adnan-syed.

- “What We Know,” episode 12 in Serial: Season One. Available at serialpodcast.org/season-one/12/what-we-know.

- “What the Hell Did I Do,” The Jinx, episode 6 (2015), directed by Andrew Jarecki.

- Ibid.

- It is telling and more than somewhat ironic that Durst’s initial offer to participate in Jarecki’s project, revealed in episode 1, was that he was “not interested in doing the true-crime kind of stuff,” that “you [Jarecki] know more about Robert Durst than any of those people do.”

- Ann Rule, The Stranger Beside Me: The Shocking Inside Story of Serial Killer Ted Bundy (New York: Gallery Books, 2018), p. xxxix.

- Michelle McNamara, I’ll Be Gone in The Dark (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), p. 1.

- Capote in an interview with George Plimpton, “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel,” The New York Times Book Review, 16 January 1966. For more on Capote’s “absent presence” throughout In Cold Blood, see David Schmid, Natural Born Celebrities, pp. 190–196.

- One long-running segment, the “TD Line-Up,” is particularly notable in this regard. The Line-Up featured a real-time list of wanted criminals, complete with photographs and identifying features “furnished by law enforcement agencies,” and offered a large monthly sum as a reward to readers who provided “authentic information” about them. In a blunt effort to encourage reader participation, the magazine boasted a running tally of criminals apprehended via this method—by 1958, for example, a total of 217 captures and $41,670 paid by the magazine.

- This sense of hybridity—and its tantalizing implications for narrative—is frequently emphasized in the spate of “how-to” guides on true crime writing published in the last three decades. Tom Byrnes, for example, urges prospective true crime writers to apply “the narrative techniques of the best fiction with the grim realism of nonfiction reportage.” See Byrnes, Writing Bestselling True Crime and Suspense (Rocklin, CA: Prima Publishing, 1997), p. 8.

Lukas Cox is a writer and filmmaker based in Los Angeles. He is currently working on an upcoming documentary series for Hulu.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.