A Stamp on History

Remembering Deir Yassin

Hunter Dukes

His stamp collection is spread over the mattress – stamps of all sizes, large and small, squares and rectangles, with differently coloured serrated edges. Among them I see one with strange angular lettering. It looks ancient, pharaonic. I read the small Arabic script: Israel. When I point to it, my uncle puts his stubby finger to his mouth and whispers, “Hush.” He turns his head to look around him, as if to see whether anyone has overheard us. Silently, I scrutinise the stamp more carefully. I am curious about the image on it. It is of an extended arm with strong fingers gripping an orange and white flower. What sort of body produces such a grip? I imagine broad shoulders and thick rippling muscles. Could that unreachable land be peopled by giants? There is writing on the side in Roman script, which I can’t read. I ask my uncle to translate and he tells me it is French for “the conquest of the desert.” I ask what conquest means and he explains.[1]

—Raja Shehadeh

On 9 April 1948, Zionist paramilitaries attacked the Palestinian village of Deir Yassin, a hillside community some five miles west of the Western Wall. During this early Friday morning, around 130 soldiers climbed up from the southeastern valley abreast quarried limestone veins.[2] The New York Times would hastily report that they encountered an “Arab force” of “2,500 men.” [3] Present-day historians put the population of Deir Yassin closer to 700, less a force than a village. The soldiers systemically massacred approximately ninety-three unarmed Palestinians, two-thirds of whom were children, women, and men over the age of sixty—this number does not include combatant deaths.[4]

This conquest was an early salvo of David Ben-Gurion’s Plan Dalet, a program to ethnically cleanse Palestinian communities and establish a Jewish state across the whole of Mandatory Palestine. Liaising with neighboring settlements, Deir Yassin had previously reached a non-aggression pact ratified by Haganah, the central Zionist military organization in Jerusalem; by approving the attack proposals of two offshoot ultra groups—Irgun (aka Etzel) and Lehi (aka the Stern Gang)—Haganah’s leadership tried to insulate itself from backlash.[5] A commander for this unit would come to admit that, in the events leading up to 9 April, “there was not even one [hostile] incident between Deir Yassin and the Jews.”[6]

An embedded Haganah member who witnessed the killings claimed that this was “a massacre in hot blood, it was not pre-planned,” but the events that unfolded in Deir Yassin that day cannot be deemed an aberration.[7] An Irgun leader recalled that “the majority [of his organization] was for liquidation of all men in the village and any other forces that opposed us, whether it be old people, women or children.”[8] Fahim Zaydan, who was a twelve-year-old resident of Deir Yassin at the time, described the indiscriminate murder she had witnessed. “They took us out one after the other; shot an old man and when one of his daughters cried, she was shot too. Then they called my brother Muhammad, and shot him in front of us, and when my mother yelled, bending over him—carrying my little sister Hudra in her hands, still breastfeeding her—they shot her too.”[9] Machine guns, knives, and bombs were the soldiers’ weapons. It was reported that they stripped women of jewelry and clothing; eyewitness testimony and later investigations suggested multiple instances of sexual assault.[10]

By the early afternoon, captives from the village were loaded into seized trucks, taken to Jerusalem, and paraded through the streets. Still others were relocated to East Jerusalem. The dead were buried by bulldozer in a nearby quarry, which had been a longtime source of prosperity for Deir Yassin’s residents. News and distortions of the massacre spread rapidly and helped precipitate the Nakba, when a nascent nation displaced approximately 750,000 Palestinians from their homes, land, and country.[11] Many other massacres soon followed. “As in Deir Yassin, so everywhere, we will attack and smite the enemy,” Israel’s future prime minister Menachem Begin, then a member of Irgun, would declare. “God, God, Thou hast chosen us for conquest.”[12]

Today, the former site of Deir Yassin is home to the Kfar Shaul Mental Health Center, a leading institute for the study of Jerusalem Syndrome, a form of religious psychosis. Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, is a few minutes’ drive away.

Postage stamps are sticky things. An ignored coda, a preface neglected: stamps are the last glimpse of a missive dropped into a mailbox; they catch the recipient’s eyes before she has time to tear the flap. They are a duty, or rather, evidence of duty exacted. In the case of international mail, stamps traverse a quartet—sender to receiver, state to state. They are issued by a nation and often commemorate it as so; without a bilateral treaty, postage goes nowhere. Letters enter archives while stamps get shorn from their words, preserved in manila folders and philately sleeves. They rarely return to their origin, and if they do, it is under cancellation, effaced enough to make them void.

Beginning in 1965, a series of stamps was issued by the Arab Postal Union ahead of the twentieth anniversary of the Deir Yassin massacre. Egypt (then the United Arab Republic), Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Kuwait, Algeria, Jordan, and the Yemen Arab Republic all offered variations, sometimes more than one, on a similar design.[13] It shows a map of Mandatory Palestine with a dagger plunged in its center—black and red blood pools between the River Jordan and Gaza. The iconography was intended “to symbolize that Palestine is bleeding and to honor the martyrs who fell,” writes Michael Sharnoff, and to recognize that Palestine’s borders “span from the River to the Sea.”[14] As opposed to the strong arm of the state described by Raja Shehadeh above, no hand thrusts this dagger—the action is complete, we are left only to witness the aftermath.

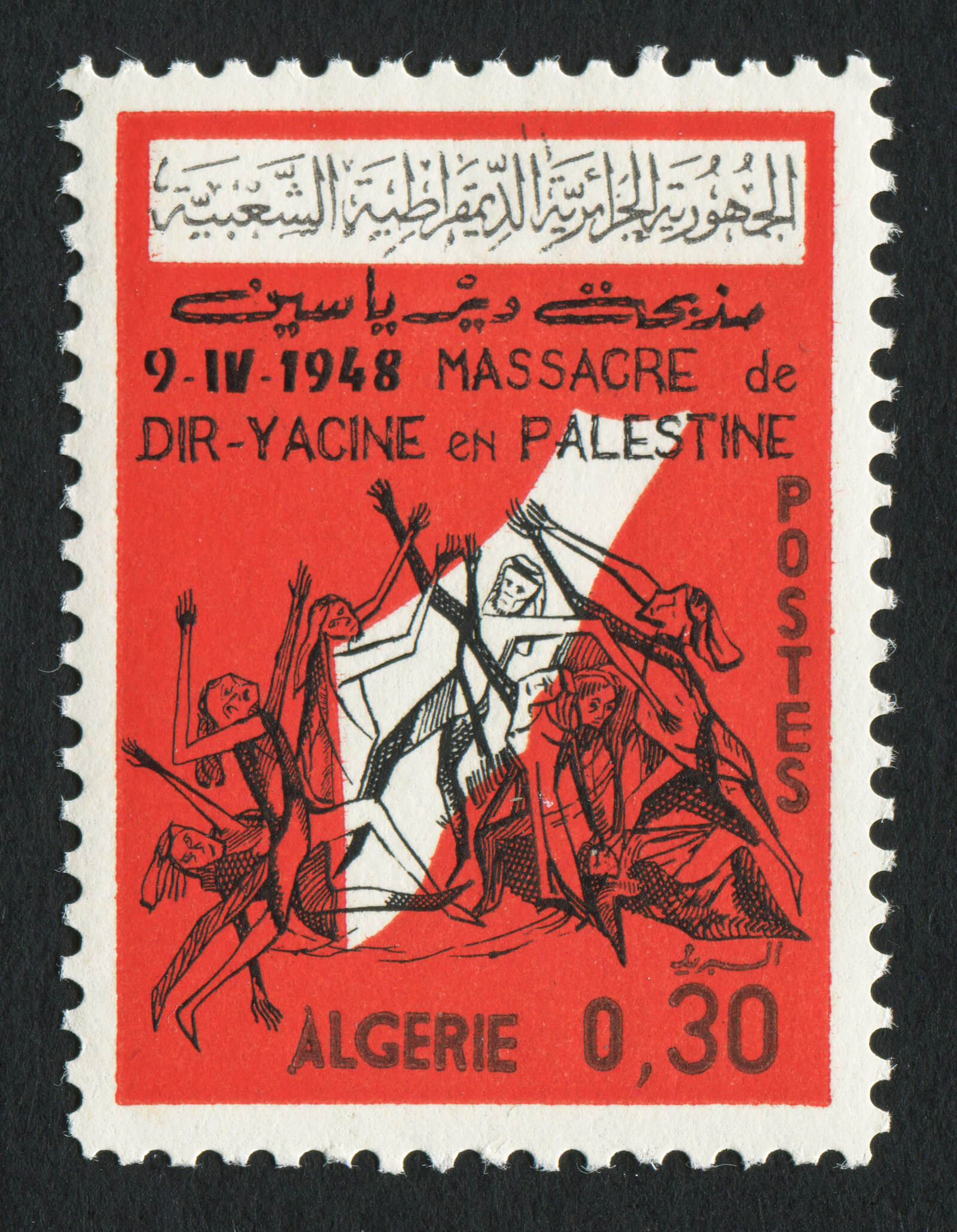

There are differences between the stamps. Their colors vary widely, as Palestine appears olive green, Tyrian purple, and numerous shades in between. A radial sun sometimes illuminates the weaponry; Acre, Haifa, Jaffa, and Deir Yassin are labelled in different Arabic hands. Half of the daggers have curved bodies and spiraled pommels with a cross guard shaped like an integral sign. The others are tapered blades with quillons slightly bent at their ends. The Algerian stamps differ significantly from their sister specimens, and were released later, on 24 September 1966.[15] Against the cartographic backdrop of Palestine, women and children writhe in Guernica-like agony.

A dagger plunged into a nation can be a double-edged symbol. Here the iconography is not so much vengeful as eulogizing. The imagery strikes a similar tone to that found in Iraqi poet Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati’s 1956 series “Odes to Jaffa”: “O Jaffa, your Jesus is in bonds. / Naked, daggers tearing at him, beyond the crosses of borders.”[16] The plight of individuals and communities is mapped onto landscape and territory. When employed by the Arab Postal Union, the dagger—no matter its form or provenance—strikes a chord of pan-Arab strength and solidarity. From at least the early 1980s, this iconography was appropriated by Israel’s supporters to symbolize Arab aggression. Filastin al-Thawra, the former PLO weekly, reported on Israeli descriptions of the Gaza Strip as “a dagger plunged into Israel’s side” on 20 January 1980.[17] The ex-CIA officer E. Howard Hunt—one of Nixon’s “plumbers” and an architect of the 1954 coup in Guatemala—published a novel in 1981 whose cover shows a bloody dagger bisecting the Star of David.[18] (Its subtitle gives the gist: “A Novel About the Arab Plan to Explode an Atomic Device above Tel Aviv.”) Israeli foreign minister and future prime minister Yitzhak Shamir—once a member of both Irgun and Lehi—called the 1981 Fahd Peace Plan, which asked for a return of Israel’s 1967 land seizures, “a dagger to be driven into our heart.”[19] David R. Blumenthal, a retired professor of Judaic Studies, maintains a database of stamps that he and his students have labelled as “Anti-Israeli.” Among a list that includes a 1968 stamp for “International Human Rights Year for Palestinian Refugees,” we find the Deir Yassin design, described as “a propaganda stamp directed against Israel.”[20] This last interpretation depends on a different reading of the stamp, one Blumenthal shares with the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith’s 1981 claim that the postage shows “a bloodsoaked dagger aimed at the Jewish state.”[21] This claim seems less convincing—although the valence is perhaps present, no matter the original intention. Yet if the stamps were meant to denote Israel in 1965 (and not the landmass of Mandatory Palestine), why not depict Green Line borders or explicit Israeli iconography? What’s more likely: that the Algerian variants—one of which shows innocents bleeding out across a map of Palestine—radically break with the other stamps in their theme of commemoration? Or that the Arab Postal Union’s daggers mark not a call to aggression but a still-bleeding wound?

Founded in April 1952, the Arab Postal Union was one of several organizations created by the Arab League, along with the Arab Telecommunications Union (1953) and the Arab Development Bank (1959), to coordinate economic life between member states.[22] Postage stamps had circulated through Ottoman Palestine since 1863, while Britain issued 104 stamps distinct to Mandatory Palestine between 1918 and 1942.[23] After Gaza fell under the United Arab Republic’s control in 1948, stamps were supplied for a time directly from Egypt—images of the Nefertiti Bust and scenes of industrialization overlaid with the word “Palestine”—and Jordan overprinted its own stamps for use in the West Bank prior to annexing it. What makes the Deir Yassin stamps unusual is their departure from self-valorization and territorial claims on the part of their issuing governments.[24]

Stamps are vectors of “visual nationalism,” writes Stanley D. Brunn in a study of postage politics—arguments for legitimacy, lionization, and heritage.[25] They often become propaganda for state narratives and imagined communities, serving as frames that envelope every communication. When sent out to distant stations, they are propaganda in an older sense: that which spreads or propagates. Online auction websites list Deir Yassin stamps still affixed to envelopes. Images of a bleeding Palestine arrived in postal boxes around the world; one envelope currently for auction was sent from Kuwait to Appleton, Wisconsin.[26] These envelopes also reveal a coordination between the handstamps used for postmarks by members of the Arab Postal Union in this period. Letters from Cairo were postmarked with an image of a dagger and blood but no landmass; an envelope originating from Iraq is stamped thrice with circular postmarks that commemorate Deir Yassin in Latin and Arabic script.[27] But what remains most striking is the geographic autonomy embossed on the postage. In an era when the Arab League’s politics were anything but fully aligned, the Postal Union chose to depict Palestine as a sovereign territory, cartographically free from the encroachment of settlers and neighbors—wounded, but still whole. And by doing so, they mailed an alternative future into the world.

It is impossible to reconstruct what effect these images might have had on their addressees. Whether they found themselves overcome with grief, encouraged toward action, or if they simply allowed their eyes to glaze. Some letters likely never reached their destination; perhaps a few remain on their way. “To recall Deir Yassin is not just to dwell on past disasters, but to understand who we are and where we are going,” Edward Said once wrote. “Without it we are simply lost, as indeed it seems we really are.”[28]

- Raja Shehadeh, Where the Line Is Drawn: Crossing Boundaries in Occupied Palestine (London: Profile Books, 2017), pp. 1–2.

- On the region’s geography, see Andrew Ross, Stone Men: The Palestinians Who Built Israel (London: Verso, 2021).

- Dana Adams Schmidt, “200 Arabs Killed, Stronghold Taken,” The New York Times, 10 April 1948, p. 6.

- Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications, 2007), p. 91.

- “Okay you do it; we are breaking the agreement,” David Shalteil, the Haganah chief in Jerusalem, reportedly told Irgun and Lehi leadership. See Daniel A. McGowen’s interview with Colonial Meir Pa’il, a former Haganah member who witnessed the Deir Yassin massacre, in Remembering Deir Yassin: The Future of Israel and Palestine, ed. McGowan and Marc H. Ellis (New York: Olive Branch Press, 1998), p. 37.

- Yona Ben-Sassoon quoted in Matthew Hogan, “The 1948 Massacre at Deir Yassin Revisited,” The Historian, vol. 63, no. 2 (Winter 2001), p. 314.

- Meir Pa’il quoted in Eric Silver, Begin: The Haunted Prophet (New York: Random House, 1984), p. 94.

- Benzion Cohen quoted in Eric Silver, Begin, p. 90.

- Fahim Zaydan (also transliterated as “Fahimi Zeidan”) quoted in Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 90.

- For a discussion of the contentious historiography of sexual assault at Deir Yassin, see Hogan, “The 1948 Massacre at Deir Yassin Revisited,” pp. 326–328. For a wider discussion of sexual assault in the 1948 and 1967 forced displacements, see Frances S. Hasso, “Modernity and Gender in Arab Accounts of the 1948 and 1967 Defeats,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 32, no. 4 (November 2000).

- For recent figures of the Nakba, see: Ahmad H. Sa’di and Lila Abu-Lughod, Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007); Nur Masalha, The Palestine Nakba: Decolonising History, Narrating the Subaltern, Reclaiming Memory (London: Zed Books, 2012); and Voices of the Nakba: A Living History, ed. Diana Allan (London: Pluto Press, 2021).

- Menachem Begin quoted in Alan Balfour, The Walls of Jerusalem: Preserving the Past, Controlling the Future (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), p. 131.

- For a catalogue of variations, see Middle East Stamp Catalogue (London: Stanley Gibbons, 2018).

- Michael Sharnoff, “Maps of the West Bank in Jordanian Postage Stamps, 1952–1985”, Contemporary Review of the Middle East, vol. 9, no. 1 (2022), n.p. For the second quotation, see Michael Sharnoff, “Visualizing Palestine in Arab Postage Stamps: 1948-1967”, Middle Eastern Studies (21 February 2024), p. 14. I am grateful to Emma Fenton for this reference.

- The date for this and the 1965 issuance above comes from Michael Sharnoff, “Visualizing Palestine in Arab Postage Stamps: 1948–1967”, p. 14.

- Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati quoted in Bashir Abu-Manneh, The Palestinian Novel: From 1948 to the Present (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), p. 54.

- Quoted in “‘Autonomy’ for the Gaza Strip,” Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 9, no. 3 (Spring 1980), p. 177.

- E. Howard Hunt, The Gaza Intercept: A Novel About the Arab plan to Explode an Atomic Device above Tel Aviv (New York: Stein and Day, 1981).

- Quoted in “Israeli Comment on the Fahd Plan,” Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 11, no. 2 (Winter 1982), p. 178.

- The quotation is available here: davidblumenthal.org/Stampcharts/antiIsraelstamps.pdf. Blumenthal and his students’ database of “Anti-Israeli Stamps Featured in Israeli and Topical Judaica Philately” is available here: davidblumenthal.org/Philatlely.html.

- Available at google.de/books?id=ep0rAQAAIAAJ.

- The Arab Postal Union was not meant to replace the Universal Postal Union, which has facilitated a global postal system since 1874. As the Arab Postal Union’s 1971 constitution states, “The Union, its General Secretariat and its Administrations shall co-cooperate with the UPU and its International Bureau in connection with the postal service.” Rather, the Arab Postal Union’s task was to facilitate closer coordination among member states. The 1971 constitution of the Arab Postal Union also speaks, for instance, of “tightening bonds,” adhering to the Union’s “interruption of postal relations with Israel,” using “the horn of posts and a flying pigeon” as an emblem, and “supervising the Arab Postage Stamps Museum.” See Amos J. Peaslee, International Governmental Organizations: Constitutional Documents (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1976), pp. 95–121.

- Barth Healey, “Philatelic Diplomacy: Palestinians Join Collectors’ List”, The New York Times, 19 June 1998, p. 8.

- There were some precursors for this iconography on stamps issued to commemorate the Nakba and refugees, but the vast majority adhere to nationalist themes. For the exceptions, see Calvin H. Allen, Jr., “Stamps of the Palestinian Authority: Asserting National Identity While under Occupation, 1994–2019,” in Stamps, Nationalism, and Political Transition, ed. Stanley D. Brunn (New York: Routledge, 2023), p. 277.

- Stanley D. Brunn, “Introduction: Stamps as Symbols of Visual Nationalism,” Stamps, Nationalism, and Political Transition, p. 3.

- Available at ebay.com/itm/404558218813.

- The Cairo envelope is available at ebay.com/itm/363955055654. The Iraqi envelope is available at ebay.com/itm/134840577764.

- Edward W. Said, The End of the Peace Process: Oslo and After (New York: Vintage, 2001), pp. 158–159.

Hunter Dukes is the managing editor of Cabinet

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.