Poor Connections

A long history of videotelephony

Vera Tollmann

Video conferencing becomes popular in times of crisis. During the early 1990s Gulf War and especially in the aftermath of 9/11, when executives temporarily lost trust in air travel, the use of this communication technology became more common as a business tool. This winter, the immobility and social distancing necessitated by the global spread of COVID-19 triggered again an urgent need for video conferencing technology. Almost overnight, companies, schools, and universities needed reliable livestreams; as a query in Google Trends demonstrates, searches for such tools increased exponentially in the second week of March, coinciding with the lockdown policy in Europe.[1] This was the first time that videotelephony became widely used by large groups.

Though technology of this kind may seem a recent innovation, its development has in fact taken nearly a hundred years to reach this moment—with many iterations, public demonstrations, and market failures along the way. Developers tried to couple telephony with image transmission technology, and later computers and the internet, from the very moment these technologies became available. The social use of videotelephony was advertised by AT&T and Bell Labs in the 1970s, as a promotional film demonstrates, but really only took off in the aughts with the launch of Skype as a way for transnational families to keep in touch.[2]

Following its 2011 acquisition of Skype, a company that had been founded only eight years earlier, Microsoft further developed the software to make it a more stable platform for conducting job or research interviews, which both saved on travel and also enabled conversations that otherwise might not have taken place at all. Before long, it was also being used to transmit art performances and lectures.[3] Skype still uses a skeuomorphic ringtone while the caller is waiting to be connected and its glitchy audio and video feel like a nostalgic resumption of an old pre-COVID digital practice that had been superseded by mobile applications like Apple’s FaceTime even before the advent of the new generation of Silicon Valley multi-user teleconferencing tools popularized during the pandemic, when many white-collar workers had to virtually meet with socially distant others. Skype supposedly could have had a brighter future, an article in The Verge suggests, were it not for Microsoft’s decision to promote Teams, their cloud-based videoconferencing software.[4]

In actuality, the conditions necessary for videotelephony to become ubiquitous had never converged until this moment. First, the service needs to be free of charge; the ability to meet in real life has to be unfeasible or restricted; there has to be a necessity for real-time communication; and users must have reliable broadband coverage. At the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, the number of Zoom users increased dramatically, from ten million in January to two hundred million in early April to three hundred million by the end of that month.[5] The software first won accolades for being the most convenient and reliable. It was free to use for a duration of forty minutes, though the company for a short time decided to allow unlimited free calls as a promotional deal. It later turned out that Zoom is also malware-prone and privacy-challenged. Never one to miss a lucrative opportunity, Facebook—still frequented by many despite torrents of criticism—hurriedly launched a messenger room capable of fifty simultaneous video streams. Google Meet, much like the company’s previous attempts at social apps, is less popular (as of April 2020, they had only a third of the number of users that Zoom did), and so the company is offering free access until September and an AI that they promise will cancel ambient noise. Having joined the party late, Google is hoping to seduce users with such extras, even though most video conferences take place behind closed doors with little extraneous noise to cancel.

Will video conferencing stay with us as a platform for business and teaching after the pandemic is over, or will license agreements be terminated and the applications deleted shortly thereafter? Will people instead long to have meetings in real life and to once again enjoy chance encounters, as they used to? Face-to-face conversations enable eye contact and the possibility of reading the other’s micro-expressions, whereas online meetings, with their video glitches, audio delays, and the occasional distorted ghostly voices, often feel dissociated. Those technical effects can appear uncanny and funny at the same time, as the medium reminds its users of media history itself, when, for example, humans performed as mediums, receiving messages from the beyond through hypnosis and telepathy. “Media always already provide the appearances of specters,” Friedrich Kittler writes in Gramophone, Film, Typewriter.[6]

The irritating thing about the BigBlueButton experience is that you talk most of the time to a more or less blank screen. Due to a lack of server power, the university asked in the first couple of weeks that students be muted and invisible whenever the teacher was talking. What began as a technical requirement developed into habitual black-screen anonymity, as students aimed to avoid what they describe as an unusual and mostly unwelcome invasion of their personal spaces. Onscreen, all I could see were the usernames of invisible, muted students hiding during classes. Some students feel their privacy is violated when contributing with the microphone on because unwanted background noises in a shared flat might make it into the virtual seminar space. The software’s benefits are features such as a whiteboard, recording options, so-called breakout rooms (a function that splits the group into separate audio streams for a defined amount of time), and integrability with the school’s own cumbersome learning platform. Still, for those who think critically about data-greedy surveillance capitalism, its key advantage is that it runs locally on the university’s servers.[8]

On the social level, streaming less data could be considered an act of solidarity with fellow students, since some join the virtual “room” with older computers, shared routers, and lower bandwidths.[9] But this mode also turns out to be a less tiring form of co-presence since there’s no need to worry about one’s self-presentation. One might think that this upside would be undercut by the fact that we can no longer see others’ gestures and facial expressions, but in fact signs of agreement, incomprehension, or disagreement are almost impossible to convey in video conferences, unless you signal emphatically using an emoji, or mime like an actress in a silent movie. In addition, one might want to argue—given that the technological convergence of originally discrete devices has been a feature of the evolution of videotelephony across the twentieth century—that this is a moment to resist being subsumed into the massive consolidation of multiple media, even if this refusal comes at one’s own expense in the form of poor user experience. This is in no small part because the strategic erosion of privacy that is fundamental to the business model of Silicon Valley corporations is abetted by all media usage ending up on one device. And one final argument in favor of those absent faces, this too unrelated to sociality: our ecological footprint is much smaller without video streaming, which is why Tom Holert suggested at an early stage of the lockdown that cultural institutions reduce their electricity consumption by limiting livestreaming, which should be reserved only for medical and educational contexts.[10]

At that time there were two directions of development for television—wireless broadcasting and wired transmission over telephone lines—and the research field was crowded. In 1927, AT&T—apparently with no knowledge of the work of Dieckmann or other engineers in the German-speaking tech bubble—successfully demonstrated the possibility of using the emergent technology of television to transmit an image-signal over phone lines. The demonstration essentially amounted to a one-way TV signal, sent via wire, that transmitted images of Herbert Hoover, then US secretary of commerce, in Washington to the president of AT&T, Walter Gifford, who was at the company’s headquarters in New York. (This was followed by a blackface skit to demonstrate “live” television.) The two men could speak to each other, and the visual signal from the camera trained on Hoover was also sent “over phone lines at the rate of eighteen frames per second,” which resulted in a poor image.[13] By 1930, AT&T had established a system capable of making two-way videophone connections between its Bell Laboratories and its headquarters, both in New York City; christened the Iconophone, the setup “sutured the audio and the visual into a single communicative space.”[14]

At the same time as AT&T was conducting its experiments, Fernseh AG—a partnership established by a number of pioneering radio and film equipment companies such as Bosch, Zeiss Ikon, D. S. Loewe, and Baird Television—and the Deutsche Reichspostzentralamt (the German national postal service) were developing their own research.[15] They presented an early prototype of a “television-telephone” service to the public in 1929, first at the 6th Great German Radio Exhibition in Berlin and then at the Deutsches Museum in Munich. Masterminded by a German engineer named Günther Krawinkel, the technology involved separating the image into thirty lines and recomposing it on a screen. A television-telephone had had a fantasy cameo in the technology-driven urban future modeled in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

The scene in which the imaginary communication system is shown had to be filmed with a special-effects technique called “synchronized projection.” And even earlier, it had been popularized in stories by Jules Verne, which might have served as the inspiration for Lang.[16]

At the 1928 edition of the annual German Radio Exhibition, mechanical engineer Dénes von Mihály, who had moved from Budapest to Berlin four years earlier, presented his publicly funded research on televisual transmission. His television receiver prototype, named the Telehor, and a device developed for Telefunken by August Karolus, were the first receivers with tiny screens presented to the general public. But Milhály intended his television research not only for public broadcasting, but rather for military and police use. He even advocated equipping airplanes with the new technology for espionage and monitoring department stores via cameras and screens.[17] In these early years of laboratory trial and error, before receivers entered living rooms, it was world exhibitions, post offices, and specially arranged press events—as in the case of Hoover and Gifford—that offered occasions for public demonstrations. In February 1928, Mihály, who was said to be particularly good at gathering journalists in his Berlin laboratory to spark publicity and garner political support, had demonstrated at one such event the successful transmission of a still image via a telephone line.

The technology’s early adoption as a tool for surveillance and forensics is evidenced in Wer fuhr IIA 2992?, a propaganda film that the Nazis produced for the 1939 Postal Union Congress in Buenos Aires.

The film, whose title means “Who was driving the vehicle with license plate IIA 2992?,” is the story of a fictional hit-and-run case in which a gas station attendant is asked to identify the driver in a virtual lineup. In the film—which its writer conceived after seeing a television appeal for the public’s help in solving a real murder case—the attendant notices that a car that pulls into his station has been damaged in an accident. That same evening, an announcement is made on TV that police are trying to identify the driver of a hit-and-run vehicle. The attendant remembers the license plate of the damaged car and informs the police. He is then asked to remotely identify the driver by means of a kind of television intercom. But it turns out that the owner of the car brought in for identification was not the driver. Instead, the gas station attendant later recognizes the guilty man when he sees him by chance in the audience of a horse race being shown on the television in the investigating commissioner’s office. Since the publication of George Orwell’s 1984, there has been an intense and ongoing scrutiny of the connection between communication technologies and surveillance, but what is surprising is that almost as soon as television went on air, it was being pressed into service as a tool for forensics.

In 1936, the year of the Berlin Olympics, selected post offices in German cities offered customers a new service in the form of TV-based viewphones. In contrast to the wireless technology being used by the German state broadcasting corporation, the postal service decided to use a completely new system for the transmission of video and audio signals, namely a modern coaxial cable. That year, Fernkabel 501, the world’s first broadband cable for videotelephony and television, connected Berlin and Leipzig to mark the opening of the Leipzig Trade Fair, transmitting videophone conversations, television programs, and telephone calls simultaneously. Part of the very expensive infrastructure (just like 5G today) was a manned amplification point every thirty-five kilometers; in these repeater stations, television technicians could follow the calls and television broadcasts on control monitors. The analytical shift from apparatuses and devices to transmission and nodes, from figure to ground, was conceptualized by Geoffrey Bowker as “infrastructural inversion” to describe the fact that historical changes, often attributed to the spectacular product of an era, are often more the result of the infrastructure that enabled the development of the product in question.

As it turned out, the videophone, technically a television-telephone, failed as a user technology. In his study of television under fascism, however, media scholar Erwin Reiss argues that the costly technology was never meant for the consumer, but was instead always primarily intended for commercial and military applications; at its core, it was a new means of circulation for capital and a new means of administration for its state. Four years later, the “coffins”—as people called the dark video call booths in the post office—disappeared. After World War II, the Allies took down the entire infrastructure.

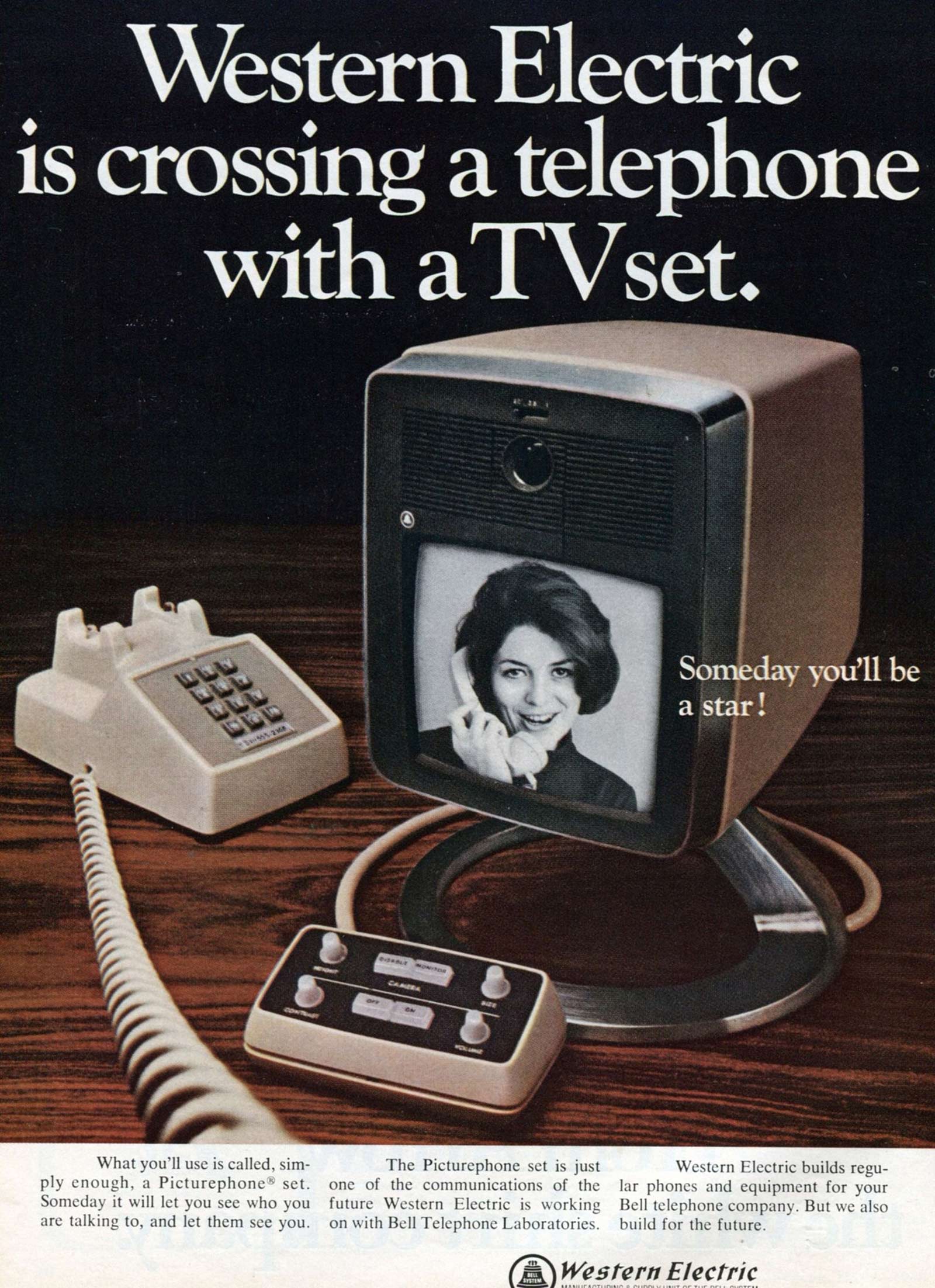

Despite these early breakthroughs in wired videotelephony, it turned out that people either felt discomfort with the video call environments—as was the case in Germany, for example—or in fact felt no desire or need for such technology. It was too expensive, and too bureaucratic. A similar story was playing out in the United States. In 1930, AT&T had demonstrated the Iconophone, its two-way visual telephone, but it would not be until 1956 before the company would try again, but its Picturephone test system was limited to transmitting a picture every two seconds, rather than moving images. When the company finally debuted its Picturephone at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, every second person who had tried the Picturephone in one of the seven calling stations at the Bell System Pavilion reported that they had felt uneasy on seeing their conversation partner represented in a vertical black-and-white picture. A similar setup would soon be tried out at Disneyland in California, and AT&T later installed family-type booths designed like private living rooms in service centers in major American cities.[18] Despite these efforts, the commercial service had little success.

In 1970, AT&T tried again with improved technology. The Picturephone Model II service was launched at eight companies in Pittsburgh, chosen because it had the first commercial radio station in the United States. In a public demo arranged for the occasion in an auditorium at the company’s Pittsburgh offices, the city’s mayor, Pete Flaherty, called John Harper, the Chairman of Alcoa, sitting a block away. The Model II had a larger screen and featured a camera with a zoom lens, a full-motion black-and-white picture with a 250-line resolution, a plug for a computer mainframe to share documents on the screen, a privacy mode that blacked out the visuals, and some graphic functions. Three pairs of copper wires were required for this phone to operate, one for the audio, and two to carry the video. Despite these improvements, the product remained unpopular, in part because the technology was perceived as intrusive. The model also failed due to insufficient resolution and extremely high prices, costing between $16 and $27 (that’s $105 to $178 when adjusted for inflation) for just three minutes of teleconferencing.[19] A postmortem study conducted by AT&T in 1974 concluded there was little demand for mediated face-to-face communication, especially in the midst of a recession.[20]

The technology was consistently plagued by the same problems, chief among them what Stewart Brand pinpointed in 1987: “The bandwidth bottleneck is the eternal bugaboo of communications technology: it governs the amount of data a medium can transmit per second. The reason we don’t have wonderful cheap picturephones is that you can’t squeeze all the information needed for good picture and sound through the ‘twisted-pair’ copper wires of conventional telephone lines.”[21]

Some of these issues finally began to be addressed in the 1990s, a pioneering decade for internet video conferencing as a result of the development of new codecs for data compression and the dotcom boom. In 1994, the eyeball-shaped QuickCam became the first consumer-grade webcam, retailing for $99. Several studies at the time concluded that an assemblage of media such as video, chat, and slides in a “universal system” was most productive in business settings and also fostered a sense of community between employees. It was also a time when researchers suggested testing stereoscopic video conferencing, which would allow algorithmically calculated eye contact between participants.[22] But the stereoscopic vision initiatives never took off, and viable video conferencing remained a fantasy through the low-fi mid-1990s. (Simulating the eye contact we experience in face-to-face conversations is still a primary focus of research and development; researchers at Intel, for example, are working on a neural network solution to this problem.)[23]

As late as 1997, German Telekom could introduce an ISDN picturephone, the T-View, and advertise it as the technology of the future. The phone, equipped with a video screen the size of a Kodak photo, was discontinued in January 2001 because by then, equipping a computer with software, a camera, and a headset cost only one-fifth of the price of the T-View. One-on-one video meetings would soon become commonplace, though group video conferencing was to remain a product of the future.[24] Until now.

One of the students in the department where I teach started a petition against the use of Zoom for university classes because he does not wish to participate in a corporately sponsored classroom watched over by surveillance capitalism.[27] In a thoughtful blog post, Simon Strick expanded on this idea, arguing that teachers are in danger of losing the crucial element of “presence” when their classrooms have to meet in “environments built around projects, corporations, positivism, monitoring, and—crucially—loneliness and absence.”[28] He has a point. But is refusal the way to go? What would we lose in doing so? Is “embracing rather than rejecting this chaos,” in front of and behind the camera, an option for both private and public gatherings?[29] So far, the digital commons have made the experience an abstract one. Or rather, as Doreen Mende has astutely pointed out, we need to discuss the techno-politics of live-streaming; at stake is the question of who has a stable connection, the latest equipment, and, therefore, smooth output, and who does not.[30] We need to be attendant to these “networked vulnerabilities,” to use Wendy Chun’s phrase.[31]

After running out of pre-uploaded backgrounds, my nephew ponders what’s next. He asks for some background noise, the sound that would come with the depicted scene: the sizzling of a steaming pot, the noise of a coffee maker, cars on a street, a conversation, the breath of a giraffe. The tiniest home turns into a green screen and anything becomes possible, like traveling the world—or perhaps, traveling among the TV products you have consumed. In times of self-quarantine, these mediated spaces become alternate hangouts. We can think of them in terms of the “no-place” of the screen, to use the phrase Kris Paulsen has suggested to describe the spatial experience of telepresence.[32] Or, are they the epitome of the “non-places” that Marc Augé had in mind when writing about shopping malls, airports, and hotel lobbies as places without windows to the outside? Or, perhaps they are embodiments of “AirSpace,” a term Kyle Chayka has coined as a description of the generic style of environments such as coworking spaces or apartments featured on home-sharing platforms.

At the end of a recent forty-five-minute student exam via Zoom, a colleague ironically told me, “This worked well. And finally, I could see where you live.” For a moment I felt embarrassed; I had not shared a revelatory view of my home, not even the notorious bookshelf.[33] I had not spent time on the mise en scène of the webcam perspective; instead, I had offered a boring blank white wall as my background.

A speaker at the Chaos Computer Club was recently quoted in a tech blog saying that the problem with apps like these is that they are often released very quickly; there are still gaps in the software, which means the users are also its beta testers. Then there is the question of tracking, data extractivism, and security bugs. Are we then doomed to soliloquize into BigBlueButton’s big black void? Perhaps we can be encouraged by the fact that Zoom has responded to criticism and changed its code? I think it’s more of an ongoing process and there are no clear choices between good (open source) or bad (surveillance capitalists), if you also take into consideration the question of the user experience. And that’s what it’s all about: striking a balance between what works and is tolerable, and what is alienating. This needs to be considered when expanding the digital commons. Instead of refusal, which results in less interactivity, demanding trustworthy data handling and a comforting interface might set in motion transformative change. Until then, the low-definition video conferencing experience will continue to feel like time travel back to the 1990s, when the digital present was defined by text chats and pixelated images. If we want a virtual sociality that everyone can participate in, for now this seems to be the best that is on offer.

- See trends.google.com/trends/explore?q=%2Fm%2F011c8m4f.

- The emergence of video calling apps for smartphones, such as Apple’s FaceTime, made video conferencing into a quotidian activity; In 2013, an ad suggested that users “FaceTime every day” by stitching together emotional scenes of people communicating via the video-calling protocol. For an anthropological take on the variety of ways in which video conversations are used, see Daniel Miller and Jolynna Sinanan, Webcam (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014). In Skype: Bodies, Screens, Space (London: Routledge, 2016), Robyn Longhurst considers mothering on Skype from a queer-feminist post-phenomenological angle.

- Shabina Aslam and Eleanor Dare, “Skype, Code, and Shouting: A Digitally Mediated Drama between Egypt and Scotland,” Leonardo, vol. 48, no. 3 (June 2015), pp. 284–285. Sometimes, those lectures failed due to limited bandwidth, for example Donna Haraway’s contribution to the documenta XI press conference at Berlin’s HAU theater, which suffered from noise and frozen or pixelated images.

- See theverge.com/2020/3/31/21200844/microsoft-skype-zoom-houseparty-coronavirus-pandemic-usage-growth-competition.

- Compare this to Skype’s rate of growth when it was still owned by its Estonian inventors; in 2006, senior Skype executive Sten Tamkivi stated: “The core of Skype, that now has been downloaded two hundred million times and we have seventy million users. … Every five days we get another million.” See “Internet Use Skyrockets in Estonia, or what is sometimes dubbed ‘E-tonia,’” Associated Press, 11 January 2006.

- Friedrich Kittler, Grammophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), p. 22.

- Ulrich Kelber, Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information, stated that Zoom is not recommended “when personal data is involved.”

- As historian Quinn Slobodian has convincingly shown in a review of Shoshanna Zuboff’s book Surveillance Capitalism, however, the surveillance metaphor might hide the fact that users are “not rendered supine.” See Quinn Slobodian, “The False Promise of Enlightenment,” Boston Review, 29 May 2019. Available at bostonreview.net/class-inequality/quinn-slobodian-false-promise-enlightenment.

- In some rural areas in Germany, internet coverage is still an issue. The German Federal Network Agency has developed an app to indicate dead spots and measure broadband access. See breitbandmessung.de/kartenansicht-funkloch.

- Tom Holert, “Reconfiguring liveness,” Rosa Mercedes, “Mutual Aid” issue, 21 March 2020. Available at harun-farocki-institut.org/en/2020/03/21/reconfiguring-liveness.

- The patent number is DE420567.

- See Albert Abramson, “110 Jahre Fernsehen: “Visionen vom Fern -Sehen,” in Vom Verschwinden der Ferne Telekommunikation und Kunst, ed. Edith Deckerund and Peter Weibel (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1990).

- Donald Crafton, The Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound, 1926–1931 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 49.

- Mara Mills, “The Audiovisual Telephone: A Brief History,” in Handheld? Music Video Aesthetics for Portable Devices, ed. Henry Keazor, Hans W. Giessen, and Thorsten Wübbena (Heidelberg, Germany: ART-Dok, 2012), p. 40. Available at archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/1867.

- See Klaus Winker, Fernsehen unterm Hakenkreuz (Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 1994), p. 24.

- See, for example, Jules Verne, “In the Year 2889,” The Forum, February 1889. Scholars now believe that this story, first published in English, was primarily the work of Verne’s son Michel.

- See Bernd Flessner, “Fernsprechen als Fernsehen,” in Der sprechende Knochen, ed. Jürgen Bräunlein and Bernd Flessner (Würzburg, Germany: Königshausen & Neumann, 2000), p. 34.

- Tobias Held, Face-to-Interface: Eine Kulturgeschichte der Videotelefonie (Marburg, Germany: Büchner, 2020), p. 54.

- Mara Mills, “The Audiovisual Telephone: A Brief History,” pp. 34–47.

- Tobias Held, Face-to-Interface, p. 73.

- Stewart Brand, The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1987), pp. 67–68.

- See Brid O’Conaill, Steve Whittaker, and Sylvia Wilbur, “Conversations over Video Conferences: An Evaluation of the Spoken Aspects of Video-Mediated Communication,” Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 8, no. 4 (1993), pp. 389–428, and Sabine Braun, Kommunikation unter widrigen Umständen? Fallstudien zu einsprachigen und gedolmetschten Videokonferenzen (Tübingen, Germany: Gunter Narr Verlag, 2004).

- Leo F. Isikdogan, Timo Gerasimow, and Gilad Michael, “Eye Contact Correction Using Deep Neural Networks,” GroundAI.com, 12 June 2019. Available at groundai.com/project/eye-contact-correction-using-deep-neural-networks/1.

- One early attempt at multi-party video conferencing took place in Japan in 2003 when Nippon Electronic Corporation (NEC) launched one of the first mobile phones with a front-facing camera, the flip phone NEC e606, back in the days when Japan was a leading player in electronics. The then-new mobile standard UMTS supported mobile videotelephony. This was the decade in which compression algorithms and picture resolution improved, and delay became less of a problem.

- See Manyu Jiang, “The Reason Zoom Calls Drain Your Energy,” BBC.com, 22 April 2020. Available at bbc.com/worklife/article/20200421-why-zoom-video-chats-are-so-exhausting.

- David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest (Boston: Back Bay Books, 1996), p. 148.

- The student’s petition is available at kein-zoom-an-der-uni-hildesheim.de.

- Simon Strick, “Digitally Drunk,” Gender-Blog (blog), Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft, 28 March 2020. Available at zfmedienwissenschaft.de/online/blog/digitally-drunk.

- Naomi Fry, “Embracing the Chaotic Side of Zoom,” The New Yorker, 27 April 2020.

- Doreen Mende, “The Live-Stream’s Split-Screen, or, Urgent Domestic Politics,” Rosa Mercedes, “Mutual Aid” issue, 5 April 2020. Available at harun-farocki-institut.org/en/2020/04/05/the-live-streams-split-screen-or-urgent-domestic-politics-2.

- Wendy Chun, Control and Freedom (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006), pp. 136–138.

- Kris Paulsen, Here/There: Telepresence, Touch, and Art at the Interface (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017), p. 14.

- See Amanda Hess, “The ‘Credibility Bookcase’ Is the Quarantine’s Hottest Accessory,” The New York Times, 1 May 2020. Available at nytimes.com/2020/05/01/arts/quarantine-bookcase-coronavirus.html.

- Alexander R. Galloway, “How Control Exists after Decentralization,” in Networks, ed. Lars Bang Larsen (London: Whitechapel Gallery and Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2014), p. 162.

- Alexander R Galloway, “Global Networks and the Effects on Culture,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 597, no. 1 (January 2005), p. 30.

Vera Tollmann is a Berlin-based writer and a teacher in digital media theory at the University of Hildesheim. Recent writing includes “Wow, that’s so postcard!” in Planet Earth (Humboldt Books, 2019) and “Proxies” (co-written with Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Boaz Levin) in Uncertain Archives, forthcoming from the MIT Press. She is co-curator of the exhibition “Sensing Scale,” which will be on view at Kunsthalle Münster in 2021.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.