Archaeology and Jihad

Baron Max von Oppenheim at Tell Halaf

Aaron Tugendhaft

Royaumes oubliés: De l’empire hittite aux Araméens

An exhibition at the Musée du Louvre, Paris, 2 May–12 August 2019

Catalogue of the exhibition edited by Vincent Blanchard

Paris: Musée du Louvre editions and Lienart, 2019

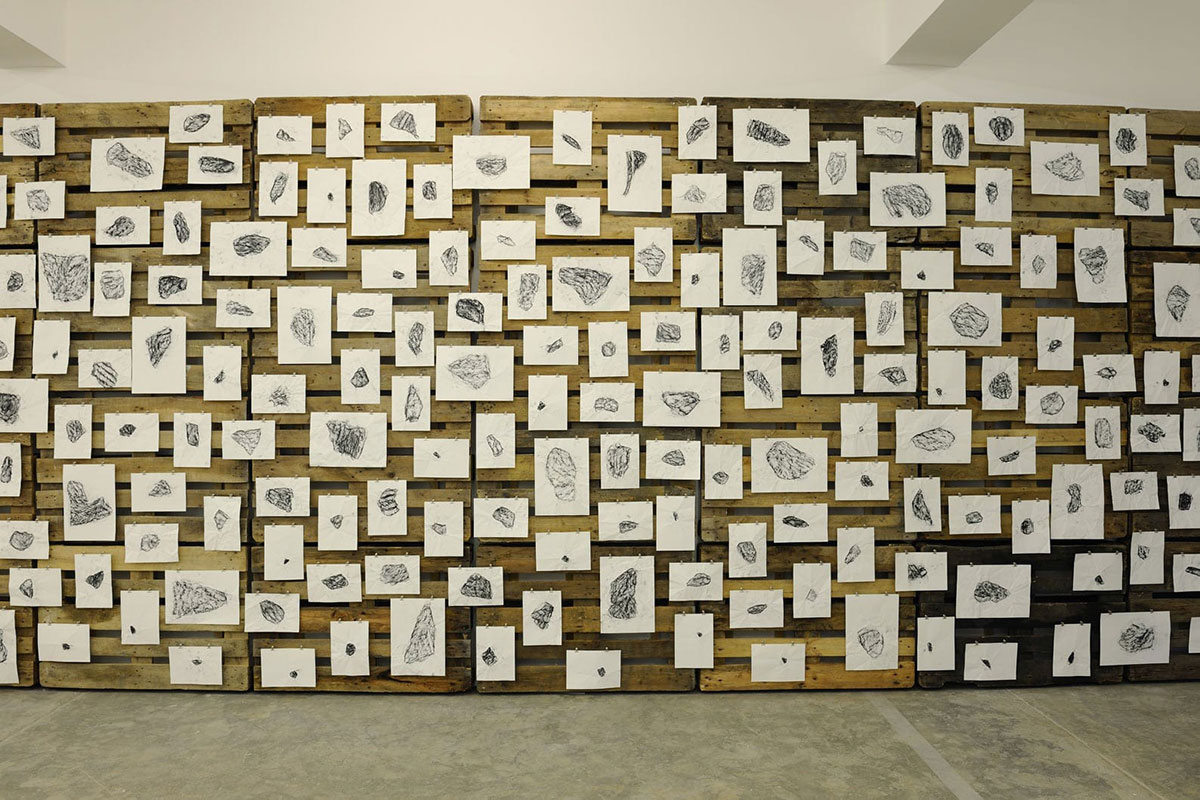

Rayyane Tabet: Fragments

An exhibition at the Carré d’Art, Nîmes, 12 April–22 September 2019

Catalogue of the exhibition by Rayyane Tabet and Jean-Marc Prévost

Beirut: Kaph Books, 2019

The museum and its contents belonged to Baron Max von Oppenheim (1860–1946). Heir to one of Germany’s wealthiest banking families, Oppenheim had acquired the artworks through self-funded excavations at Tell Halaf (ancient Guzana) in northwest Syria. He sought to display his sculptures in the Pergamon Museum on Berlin’s prestigious Museum Island, but when negotiations fell through, Oppenheim settled for a disused machine factory on the other side of town. The Tell Halaf Museum opened to the public on 15 July 1930—the baron’s seventieth birthday. Thirteen years later, an Allied incendiary bomb set the building aflame and the cold water used to extinguish the fire caused the basalt sculptures to shatter into some twenty-seven thousand pieces. Oppenheim convinced Walter Andrae, director of the Pergamon Museum’s Near Eastern collections, to salvage the remains. Nine truckloads of Oppenheim’s treasures finally reached Museum Island, but in fragments. They lingered in a cellar there for the next half-century.

In 2001, a conservation team began the painstaking effort of reconstituting the sculptures. Ten years later, a special exhibition unveiled thirty works that the team had been able to reconstruct successfully. The Pergamon Museum is currently building a new gallery to house these resurrected sculptures. While awaiting their new home, a selection of the works traveled to Paris to form the core of the Louvre’s exhibition.

To complement the works from Tell Halaf, the Louvre assembled an impressive assortment of monumental sculpture and luxury items from contemporaneous cities in northern Syria and southwestern Anatolia. Tell Halaf and these other sites flourished in the centuries following the Hittite Empire’s collapse (ca. 1200 BC). Scholars have dubbed many of them “neo-Hittite,” emphasizing their common roots in Hittite tradition; others attest the first flowering of Aramean civilization. These were small independent kingdoms that shared cultural forms while benefitting from a lull in imperial domination. To round things off, the exhibit included an initial gallery with objects from the Hittite imperial period and closed with a few items heralding the arrival of the Assyrians, who would take control of the region by the eighth century BC.

In the wake of the Islamic State’s rampage through Syria and Iraq, the Louvre spearheaded ALIPH (International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas) with support from the French government and the United Arab Emirates. The exhibition sought to reinforce ALIPH’s efforts by enlisting visitors in the fight to protect a “terribly fragile heritage common to all humanity.” From the Allied bombing of Berlin to ISIS’s ransacking of the Mosul Museum, the ghosts of antiquities destruction haunted the show.

In 1899, Oppenheim was gathering information in northern Syria when Bedouin friends told him about extraordinary stone sculptures that had been found on a nearby hill. He resolved to see for himself. After three days of clandestine digging, Oppenheim recognized that he had made an important find. “It was a turning point in my life,” he later recalled. But with neither proper tools nor permission to excavate, there was nothing more he could do. Only twelve years later—after being dismissed as attaché in Cairo for intrigues considered “a perpetual danger [and] grave menace to peace”—did Oppenheim return to Tell Halaf with a permit from the Ottoman authorities. He excavated the site until the outbreak of World War I turned his attention back to politics.

Oppenheim believed Islam was the Achilles’ heel of Germany’s enemies. From Egypt to India, the British Empire ruled over a hundred million Muslim subjects. Tsarist Russia ruled nineteen million more, and there were nearly as many under French control. If these Muslims could be incited to rebel against their overlords, Oppenheim surmised, Germany would reap the benefits. In the hundred-page “Memorandum Concerning the Revolutionizing of the Islamic Territories of Our Enemies,” Oppenheim outlined a plan to foment a global jihad. It called for the Ottoman Sultan-Caliph to issue a German-prepared fatwa declaring a Holy War against the Entente powers and to flood Muslim lands with leaflets aimed at exploiting resentment against colonial rule.

With the backing of a Foreign Office now willing to overlook his Jewish origins, Oppenheim set up a jihad bureau in Berlin that mobilized German orientalists to produce thousands of pamphlets in the various languages of the Islamic lands. “O beloved Muslims, consider even for a brief moment the present condition of the Islamic world,” one typical pamphlet began. “Wherever you look, you see that the enemies of the true religion, particularly the English, the Russians, and the French, have oppressed Islam. … But the time has now come for the Holy War, and by this the land of Islam shall be forever freed from the power of the infidel who oppresses it. … Know that the blood of infidels in the Islamic lands may be shed with impunity—except those to whom the Muslim power has promised security and who are allied with it.” (The final caveat was necessary to protect Germans and Austrians from the wrath that Oppenheim sought to unleash.)

Oppenheim’s global jihad never ignited. The baron grossly misread the situation on the ground and despite a personal relationship with King Faisal, the son of Sharif Hussein of Mecca, he was ultimately outmaneuvered by his British counterpart T. E. Lawrence in the race to win Arab support. When Hussein declared an uprising against the Turks, the plan’s legitimacy was fatally compromised. By 1915, Oppenheim’s disillusioned protégé Curt Prüfer pronounced the Holy War “a tragicomedy.”

After Germany’s defeat, Oppenheim rededicated himself to archaeology. He arranged for part of his Tell Halaf finds to be shipped to Berlin, while the rest went to the nascent National Museum of Aleppo. He spent the 1930s promoting his museum and overseeing the production of four scholarly tomes devoted to his discoveries.

The rise of National Socialism didn’t disturb the old baron. Oppenheim quickly received honorary Aryan status and was put on the Nazi government payroll. When war broke out, he again composed a memorandum recommending ways to stir up trouble for the British in India and the Middle East. But the führer wasn’t drawn to the idea of encouraging darker peoples to rebel against their white masters.

Oppenheim died of natural causes a year after the war. He had devoted his life to recovering ancient monuments and instigating modern jihad. For Oppenheim, there was no tension between the two. And yet, his jihad pamphlets paved the way for today’s Islamic State videos that provoke the colonial powers by destroying those antiquities that the West holds so dear.

In antiquity, their effect would have been further heightened by their integration into the urban fabric. Visitors to Tell Halaf’s walled ceremonial center would approach it from the south. Just before the gate, mortuary chapels with sculpted images of the city’s illustrious ancestors would remind them that the city’s well-being depended on its ties to the past. The gate’s elegantly decorated doors served to frame and order access to the ceremonial center beyond. Once inside, a plaza provided an unobstructed view of the city’s most imposing building: King Kapara’s Palace.[1]

Five towers produced a dramatic interplay of light and shadow. Along the walls, over two hundred orthostat slabs ran at eye level—alternating chromatically between dark gray basalt and red-painted limestone. Passing visitors could make out repeated scenes of hunters and wild game; a lingerer might notice the outlandish carving of a lyre-playing lion and a defecating horse, both with erect penises. The protruding bench that ran underneath the stone slabs encouraged such leisurely viewing.

But the city’s sculptural climax awaited. A street along the building’s eastern side led uphill to a second plaza. As visitors turned left into the plaza, they would suddenly be confronted by the building’s magnificent portico with its tremendous male and female caryatid figures standing on the backs of lions and bulls.[2] The impressive sculpture towered over anyone who visited. Its effect must have increased when the plaza filled with thousands of spectators to attend mortuary rituals performed before the portico. Afterwards, continued encounters with the city’s sculpture would likely have reinforced the civic cohesion forged on those occasions. Kapara was a curator as well as a king.

And yet, kings and curators aren’t always obeyed. Many neo-Hittite sculptures include inscriptions anxiously entreating those who pass to remember the glorious deeds of old—and cursing those who don’t. On a stone slab from Carchemish, King Katuwa threatens the reproductive capacity of anyone who overturns his monument or erases his name. His inscribed slab was discovered face down, reused as a paving stone in a later king’s grand staircase.

The artist has since traveled to Berlin, Baltimore, New York, and Paris to take charcoal rubbings of the now dispersed Tell Halaf orthostats. Much as the stone slabs once adorned Kapara’s palace, their paper correlates lined the walls of the Louvre exhibition’s entry hall. But paper is more honest than stone. Unlike ancient kings, Tabet claims no right to permanence for his works. His rubbings do not accost us with threats. By respecting their own fragility, these works on paper help us engage the past without an encumbering injunction to preserve it.

When the conservators in Berlin began reassembling the Tell Halaf fragments, they laid out each piece on wooden pallets that filled a vast workspace. At the Carré d’Art in Nîmes, Tabet has transformed that step in the reconstruction process into an object of reflection. His drawings of the stone fragments, each on its own sheet of white paper, have been tacked onto similar wooden pallets, but now standing vertically from floor to ceiling along an entire wall. Each fragment is drawn with a dignity that disrupts our desire to possess things whole. But, of course, it is too late. Tabet’s drawings only preserve the traces of the “fragment-sculptures” that Berlin’s curators dissolved when they reassembled the ancient works.

Tabet’s work acknowledges the fraught history that surrounds the ancient objects that we admire in our museums. They neither seek to obscure that history in veneration nor escape it through iconoclasm. Rather, his drawings inhabit the uncomfortable space between destruction and preservation. They suggest we ought to do the same.

- The name, though attested in inscriptions, is misleading since the building’s main function was ceremonial and the royal residence was located elsewhere on the citadel.

- Oppenheim rebuilt the famed portico in the Tell Halaf Museum using a mixture of original artifacts and new casts; a replica welcomes visitors to the National Museum of Aleppo. The portico will be reconstructed once again in the Pergamon Museum’s new gallery in Berlin.

Aaron Tugendhaft teaches at Bard College Berlin. His book, The Idols of ISIS: Images and Politics from Ancient Assyria to the Internet, will be published by the University of Chicago Press next fall.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.