The Veterans of Future Wars

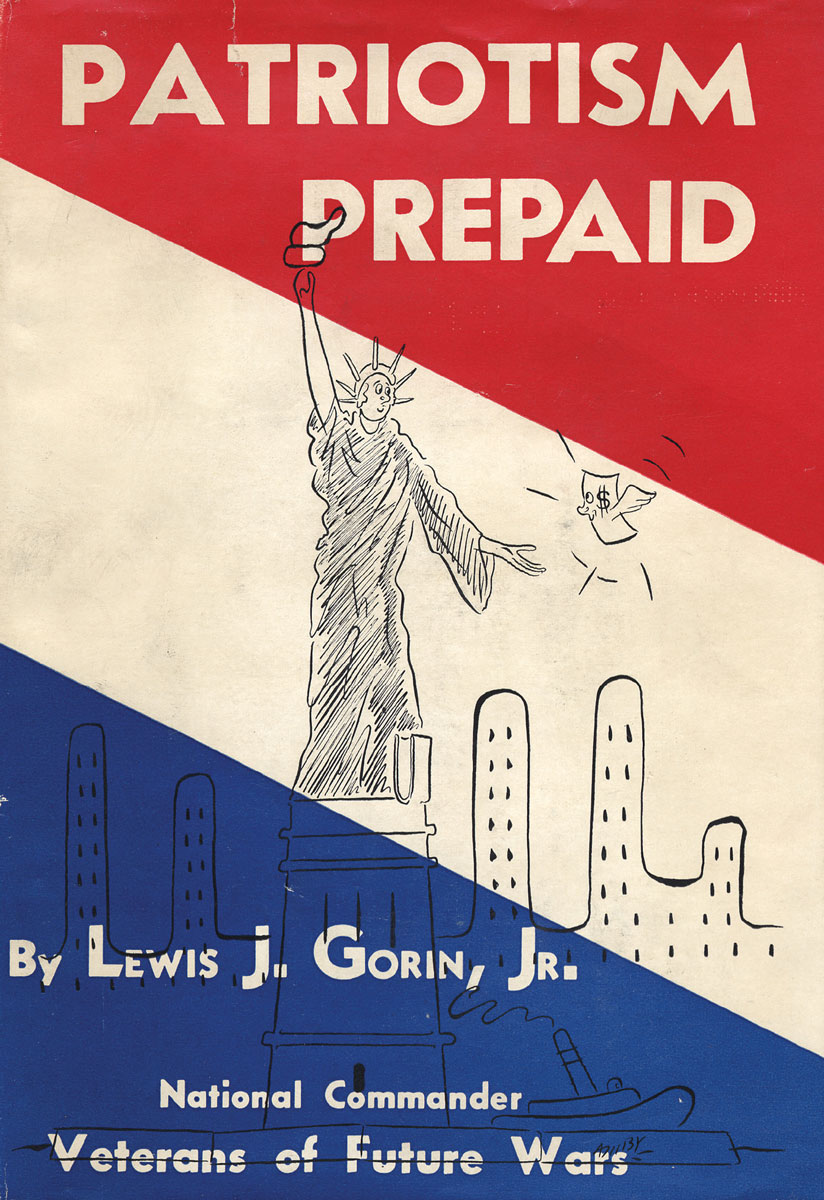

Patriotism, prepaid

Susan Hamson

“Soldiers of America, Unite! You have nothing to lose.” In a time of political uncertainty, threatening war, and economic depression, such was the rallying cry of the Veterans of Future Wars, a Princeton University undergraduate group formed in 1936 in response to the new Harrison Bonus Bill, which allowed World War I veterans to collect their war bonuses in that year rather than in 1940. The legislation, the consequence of intensive lobbying by the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, had struck the students as an unconscionable raid upon the United States Treasury for the benefit of an organized minority. Modeling their demands after the bill’s supporters, the group maintained that given the “inevitability of war,” future soldiers should be given their bonuses—$1,000 in cash—before the war as “any will be killed or wounded in the next year and, hence they, the most deserving, will not get the full benefit of their country’s gratitude.”

The students went all out. They rented office space, held a campus rally, traveled to Vassar to institute a woman’s auxiliary (the “Home Fire Division,” after the name “Future Gold Star Mothers” was protested by a disapproving administration at the school), had their own salute (“The Outstretched, Itching Palm”), and incorporated with the approval of the State of New Jersey. The Future Veterans consisted of a National Council and a network of nationwide collegiate posts. The National Council, based in Princeton and staffed by its founders from the classes of 1936 and 1937, was led by National Commander Lewis Gorin, Jr., with Jack Turner as Secretary, Thomas Riggs, Jr. as Treasurer, and Robert Barnes in charge of public relations. Riggs, Jr. shared the role of Acting Commander with Barnes after summer recess in September until the group’s disbanding in the spring of 1937. The Princeton Press Club sent out stories, the wire services got interested, and all across the country, newspapers ran articles on the Future Veterans. Overnight, local chapters mushroomed on college campuses; at its height, the organization boasted over 60,000 members and had 534 chartered posts throughout the country.

What made the Future Veterans an instant success was their appeal to both conservatives and liberals. Conservatives saw the group as a strong ally against FDR’s government spending. College liberals who were pacifist, anti-war, and anti-military embraced the opportunity to rally against war and the military. But through it all, the Future Veterans stayed true to their “cause,” and played the joke to its last breath. Indeed, Christian Gauss, Dean of Princeton, who had not altogether embraced the movement, considered that the Future Veterans “might have consequences that no one can yet see and that it demonstrates the determination of youth to rebuild the disordered world of their fathers a little closer to sanity.”

The Future Veterans were a short-lived phenomenon; formed in the spring of 1936, they just barely survived summer vacation. There was no money in the treasury, the joke was old, and national attention had switched to the Roosevelt-Landon presidential campaign. Operations were suspended in the fall, and in April 1937, with the treasury showing a deficit of 44 cents, the Veterans of Future Wars closed their books forever.

With the onset of the Korean War in 1950, some efforts were made to revitalize the group, but enthusiasm died out almost as quickly as it began. In the 1930s, anti-war sentiment was high as many watched events in Europe with great trepidation. But overwhelming US victories in World War II and the growing threat of communism made the general population less skeptical of American involvement in foreign conflicts. In this respect, the Future Veterans remains very much a product of its time. But what happened to the students who founded the organization? “With the exception of one undergraduate injured in an automobile crash in 1936,” notes historian Richard D. Challener, “every one of the Princetonians who founded the Future Veterans served in the United States armed forces after Pearl Harbor. And, presumably, qualified for World War II benefits and bonuses.”

Susan Hamson is a project archivist at Princeton University Library where she manages a staff of three in the processing of over 2,200 linear feet of University records. Previously, she was the archivist at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.