Inventory / Regalia

The decline and fall of a ribbon empire

Paul Lukas

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

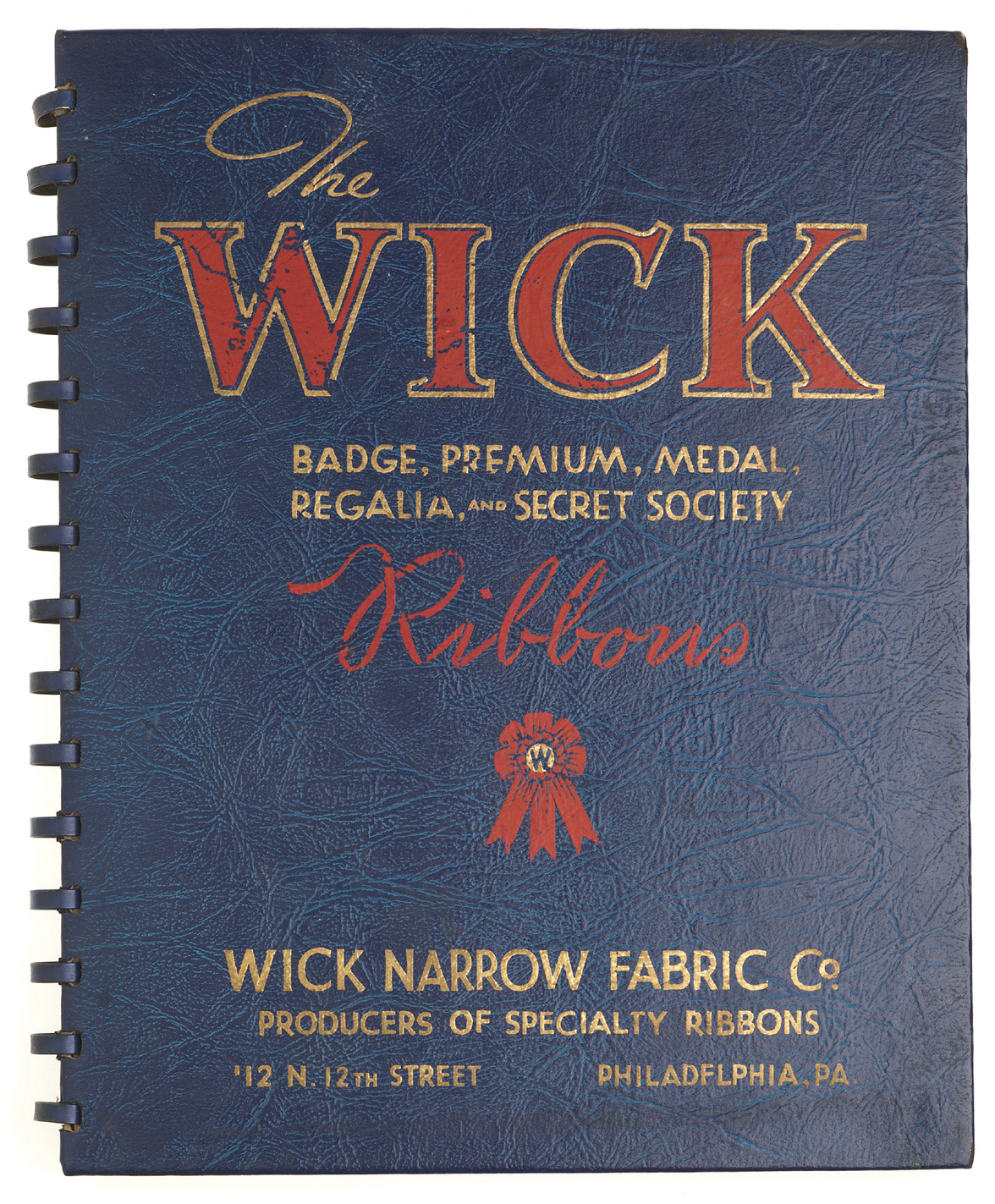

There are lots of ways to measure the changes wrought by modern life. Andy Webster measures them like this: “In the old days,” he says, “if you got a present that was wrapped with a ribbon, you saved the ribbon. Today you just toss the ribbon away.” Webster speaks with some authority on this subject, because he owns the Wick Narrow Fabric Company, a New Jersey operation that’s been making ribbons for over a century. I became interested in the firm after coming across one of its old salesman sample catalogues from the 1940s. Like most trade sample books, the old Wick catalogue provides a window into the particulars of an industry that most of us never think about. Although ribbons and ribbon imagery are fairly ubiquitous—encompassing everything from ribbon-cutting ceremonies and blue ribbon commissions to “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree”—you probably haven’t given much thought to how ribbons are designed, manufactured, or sold.

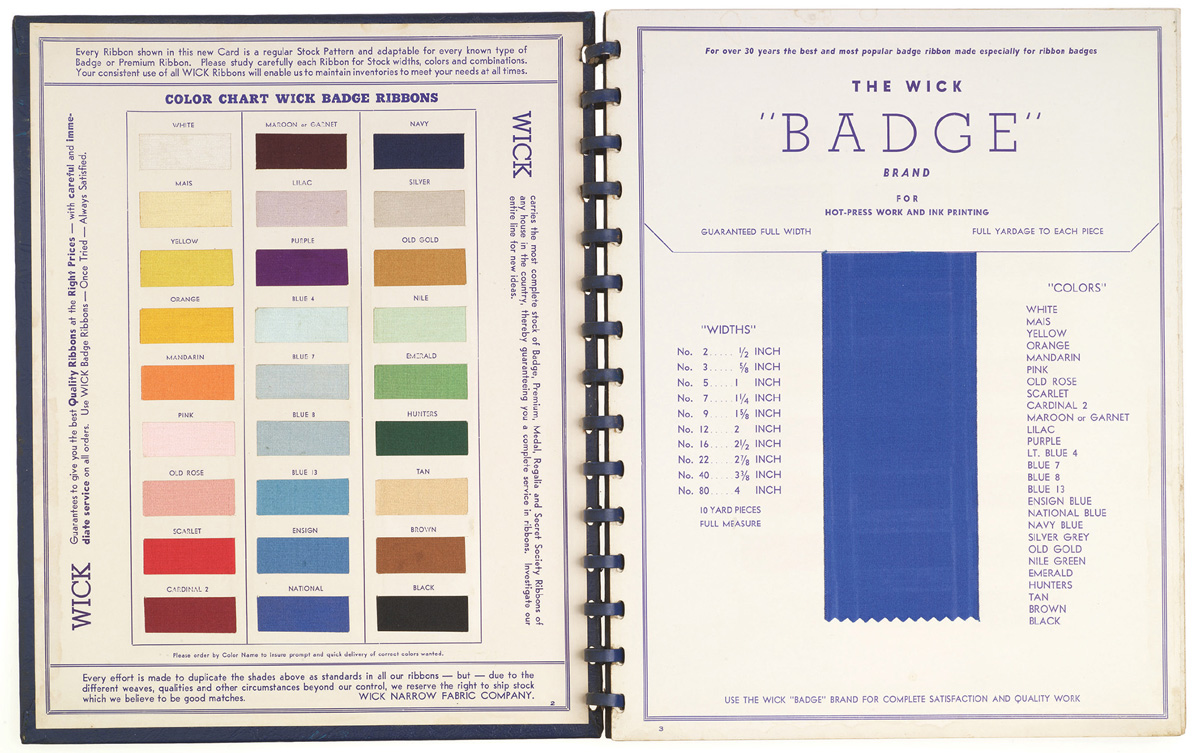

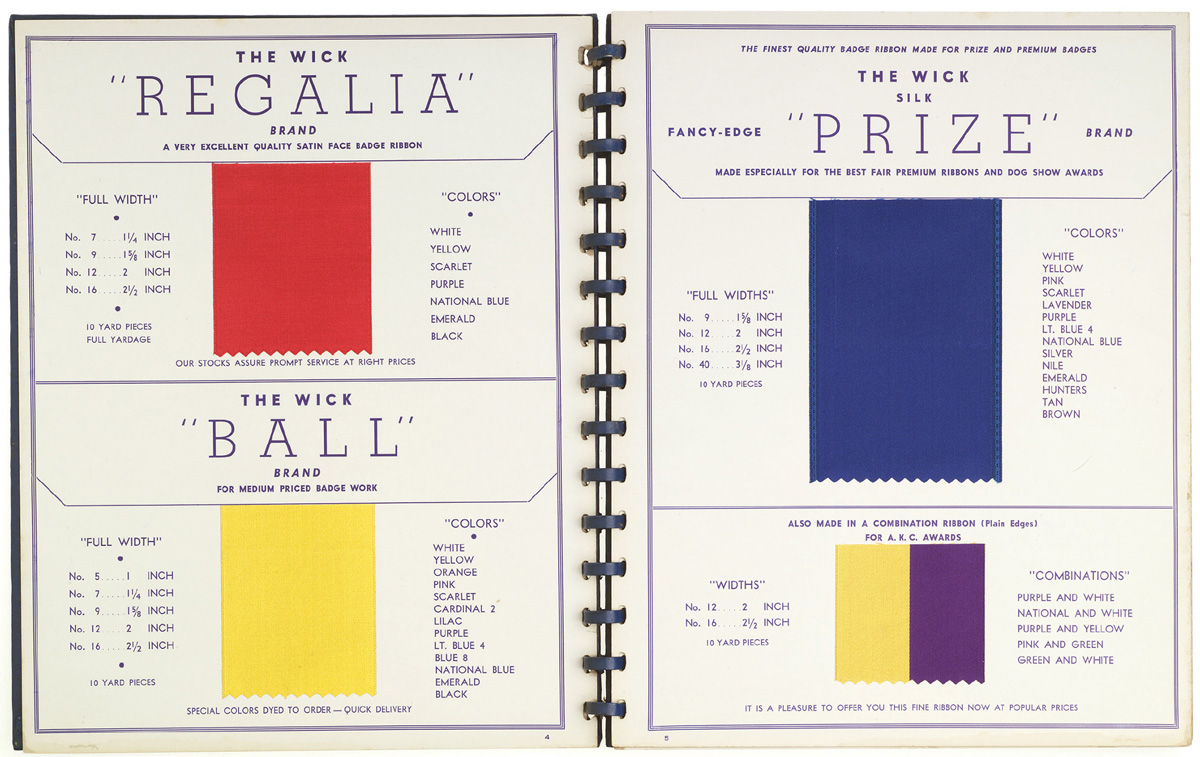

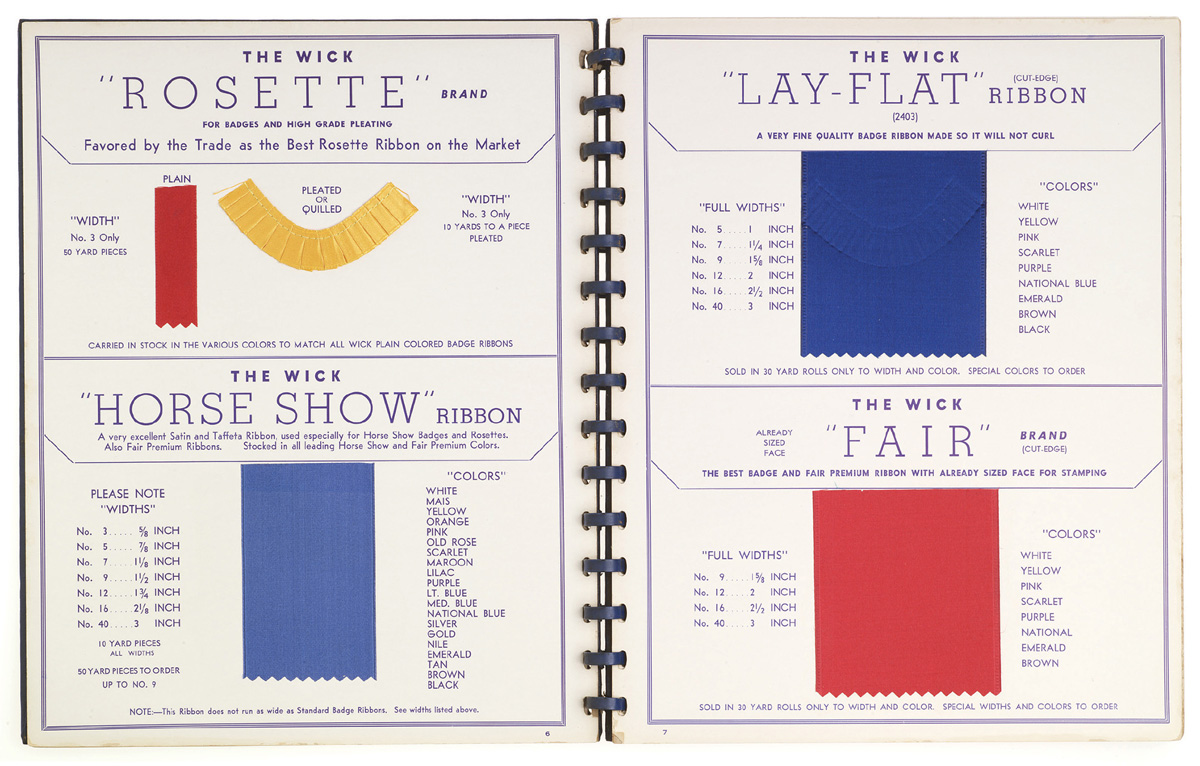

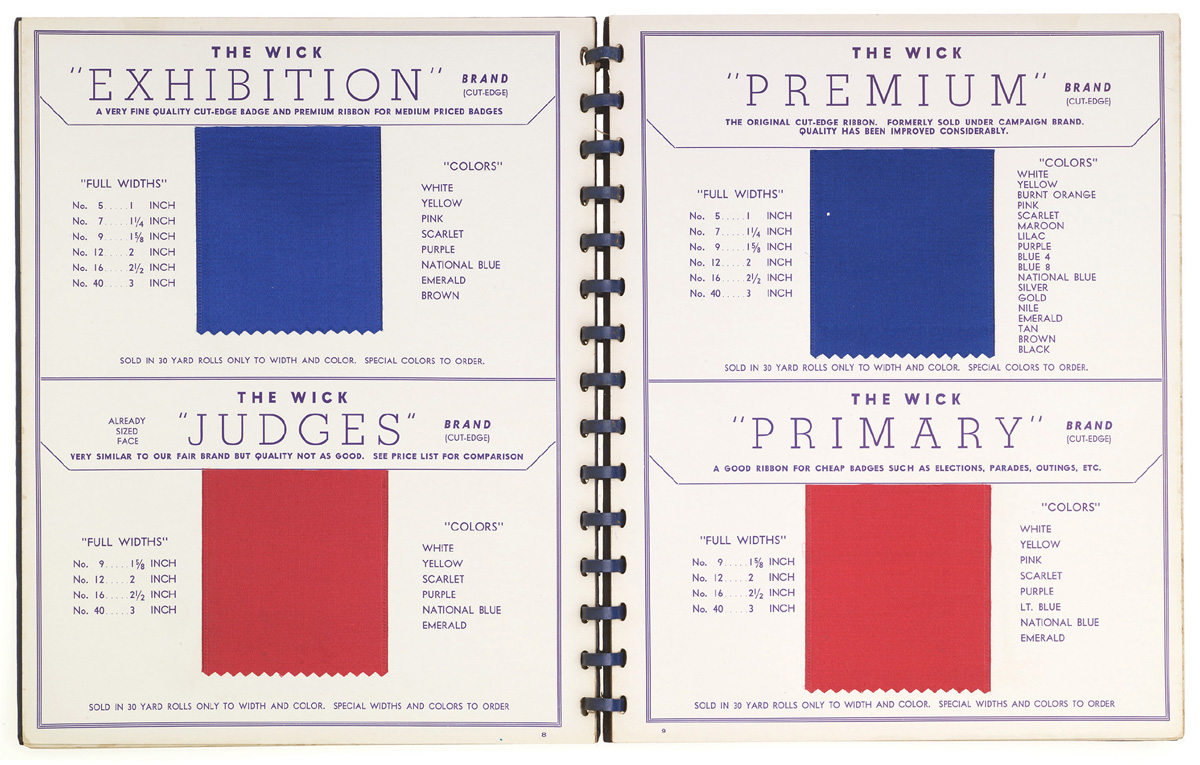

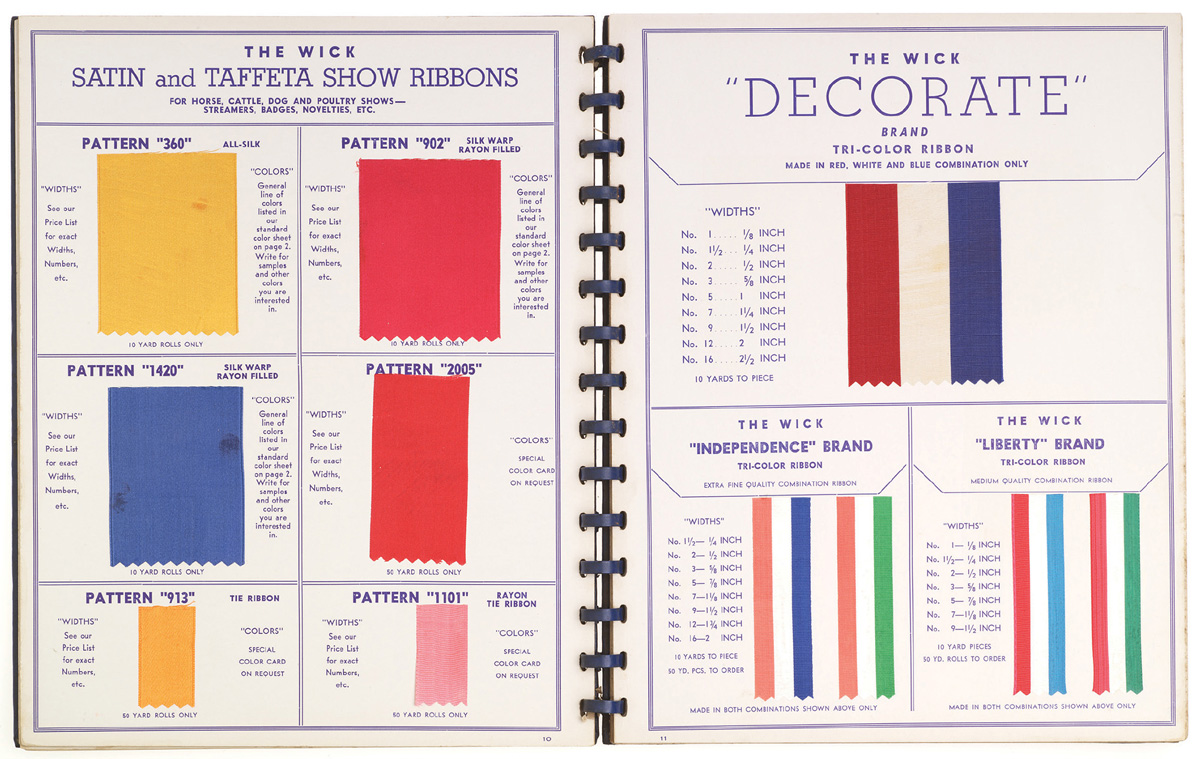

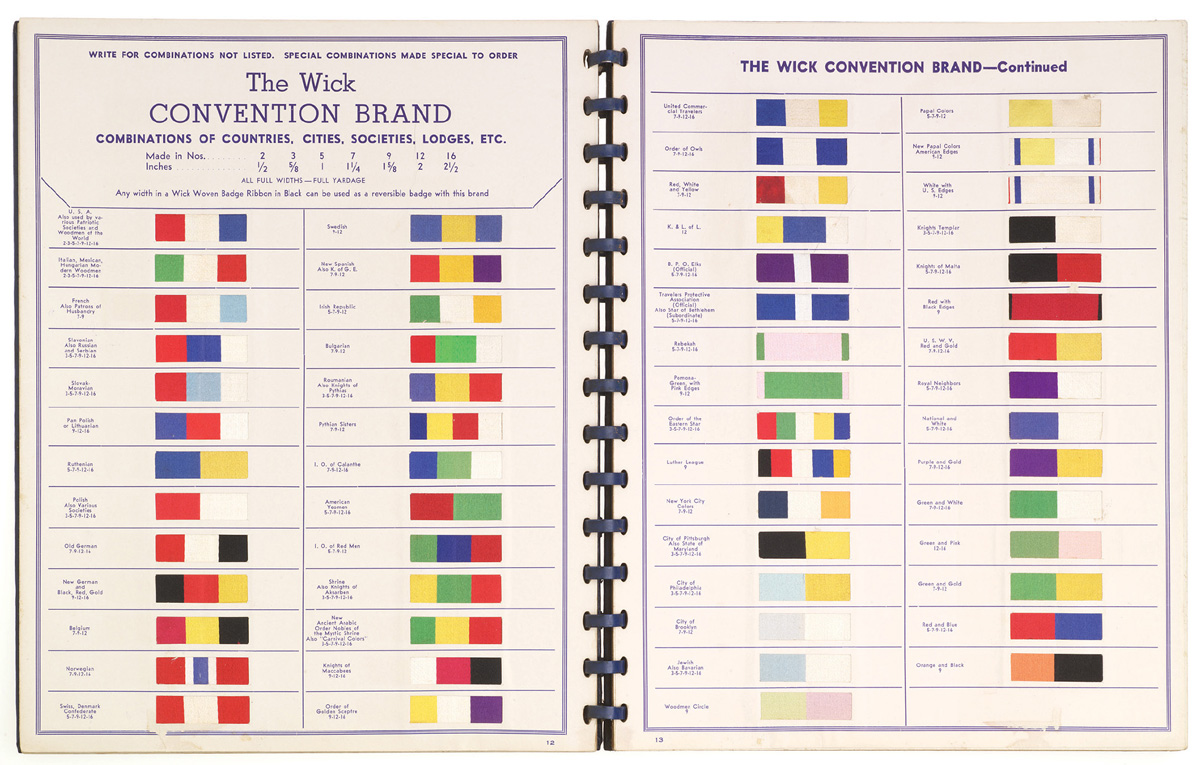

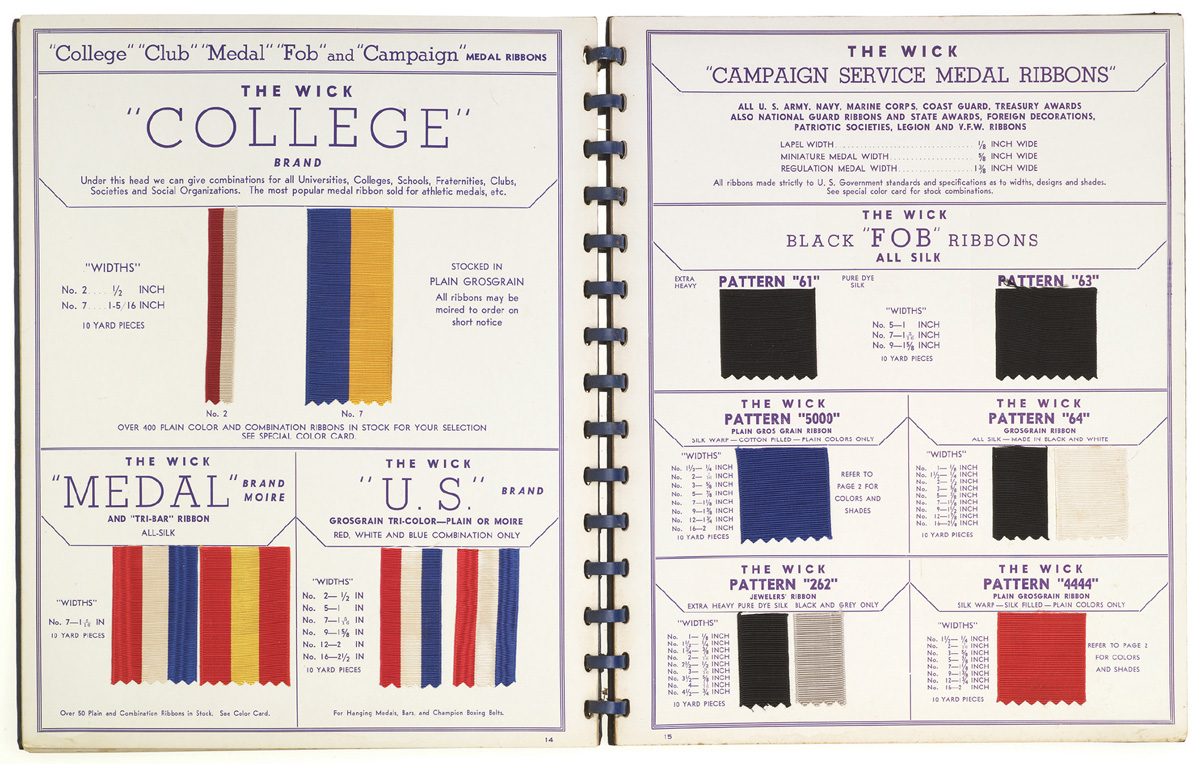

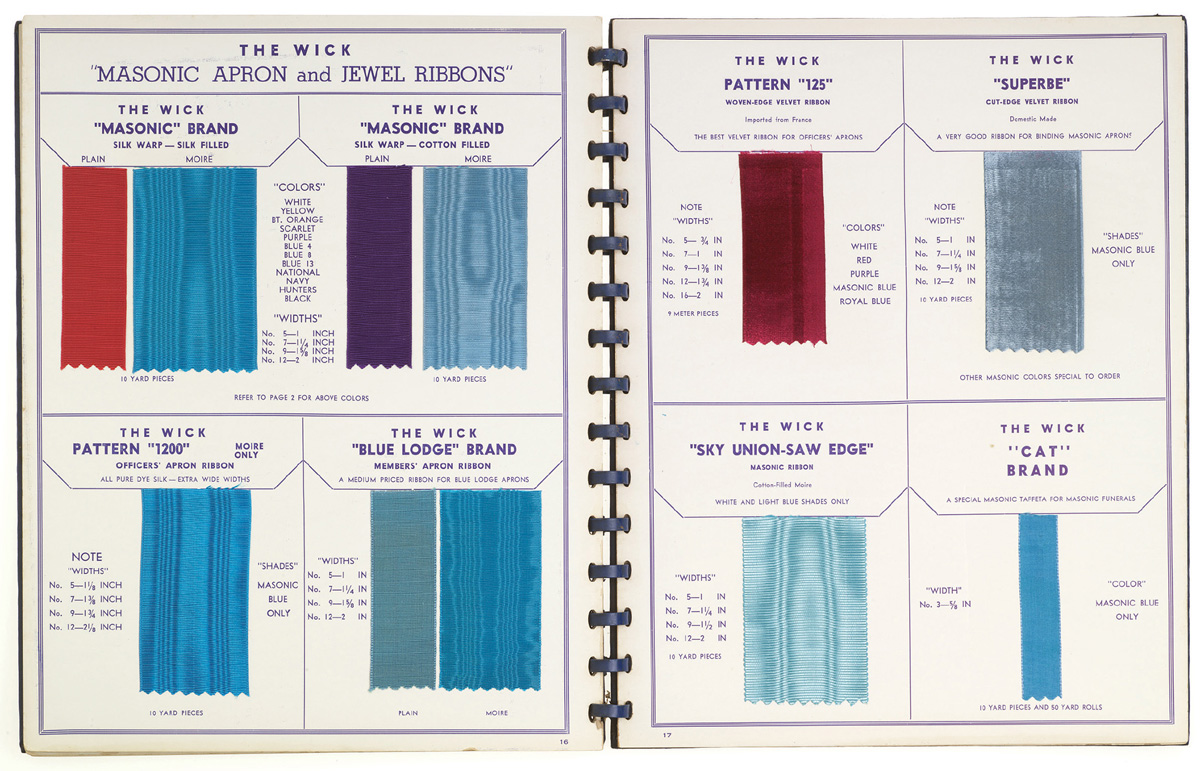

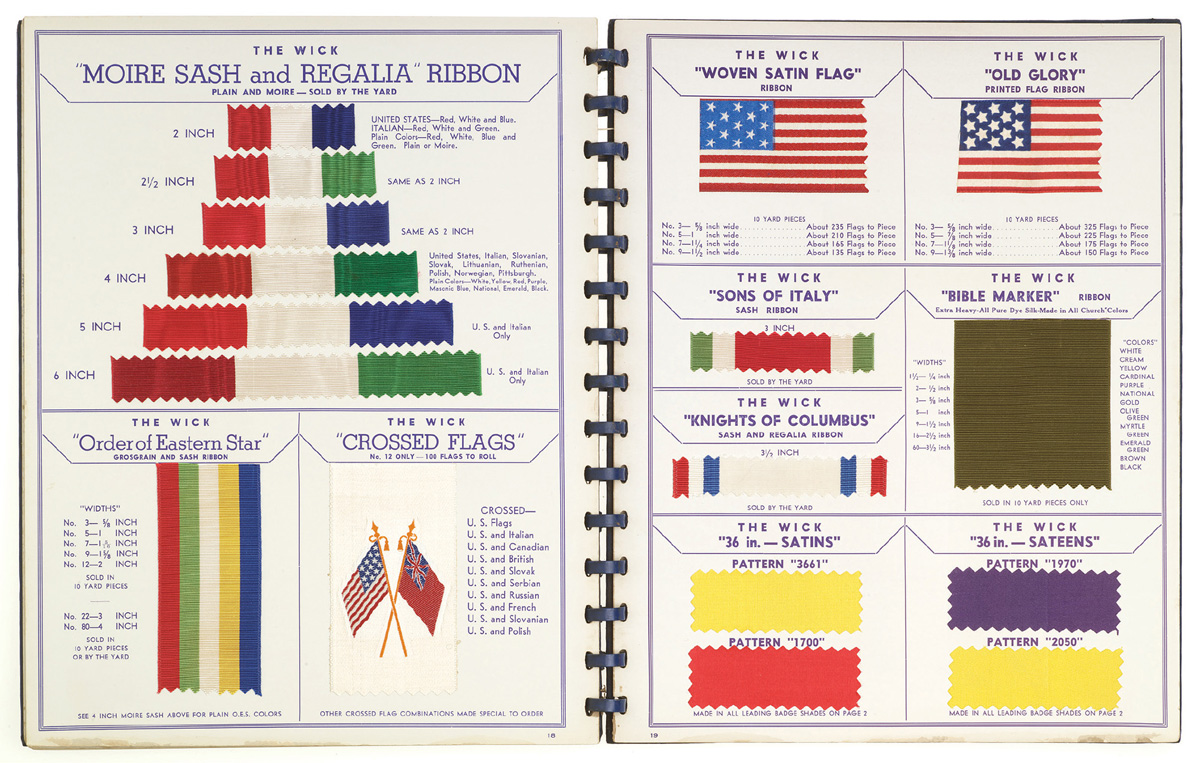

The old Wick catalogues are filled with colorful swatch samples, and hundreds of ribbon varieties: badge ribbons, regalia ribbons, convention ribbons; silk ribbons, satin ribbons, pleated ribbons; moiré and velvet, taffeta and cotton-filled. It’s a textile fetishist’s wet dream. There’s also an impressive degree of functional specificity, from awards for “horse, dog and poultry shows” to Bible bookmarks to Masonic funerals.

The funeral ribbon is part of a two-page spread of ribbons designed specifically for use by the Masons, and the catalogue also features ribbons for many other secret societies, fraternal organizations, and heritage groups, including the Sons of Italy, the Knights of Columbus, the Order of the Eastern Star, the Woodmen of the World (not to be confused with the Modern Woodmen or the Woodmen Circle, both of which are also represented), the Knights of Pythias, the Order of the Golden Sceptre, the United Commercial Travelers, the Order of Owls, the Elks, and the Luther League.

Many of these groups are now defunct, as fraternal organizations no longer play a significant role in American life. “But we still do some of that work,” says Andy Webster. “Lineage societies like the Daughters of the American Revolution, they come to us for their regalia ribbons. That’s pretty steady stuff. And we still do things for the Order of the Eastern Star and the Shriners, but probably not in the same volume as in the past. They just don’t decorate themselves like they used to.”

But if fraternal groups are on the wane, the contemporary ribbon market boasts a growth sector that wasn’t yet on the horizon in the days of the old catalogue: symbolic causes, like AIDS awareness ribbons and “Support Our Troops” ribbons (the latter of which have become so iconic that they’re now depicted on car magnets—a symbol of a symbol). “It started with the yellow ribbons for the hostages in Iran during the late 1970s,” says Webster. “If you didn’t have that product on the shelf, you were in trouble. And then after September 11, the red-white-and-blue ribbon got popular. We’d always manufactured that, so I had plenty of it on the shelf, and I sold every last stitch I had. But I didn’t run out and make more, because most of that stock had been sitting there for ten years.

It’s that kind of savvy ribbon acumen that has kept the company going since 1899, when it was founded in Philadelphia by one John Wick. The firm remained in Wick’s family until 1974, when his son-in-law’s son-in-law sold the operation to Webster’s father. “The company’s first order was for the guys coming back from the Spanish-American War,” explains Webster. “It was for the first medal that was mass-produced, called the Dewey Medal, and we did the ribbons for that. We bid on it with the federal government, and our bid was selected. It was the first piece of business we did.”

Webster, whose product is manufactured at a mill in upstate New York, says the biggest difference between today’s ribbon business and the one represented in the old catalogue is in the fabrics. “When we started, we were making ribbons out of silk. Now the industry is mostly textured polyester, which is a yarn that’s frizzed out so much that it looks bulkier than it is, but there’s hardly anything there—it’s a very cheap yarn.” Although Webster uses a filament polyester, which he says has “a silkier feel” than the textured poly, he acknowledges that standards have generally gone to hell. “If someone wants a sash, they might not care anymore if it’s an actual woven piece, or if it’s what we call a cut-edge ribbon, which is made out of a thermoplastic yarn like an acetate. You don’t see those ribbons in that catalogue you’ve got, because that technology didn’t exist until after World War II—it’s much cheaper.”

All of which helps explain why people now toss away their ribbons instead of saving them. Is Webster disappointed by the decline in ribbon standards and status? “Oh, I suppose, in a way,” he says. “But you know, time marches on.” Fortunately, a fixed moment from that march can be preserved in a document like the old Wick catalogue.

Paul Lukas lives in Brooklyn, where he writes about the picky little details of just about everything.