Leftovers / Ashes to Diamonds

Turning grandma into a Treasured Family Heirloom™

Tom Vanderbilt

“Leftovers” is a column that investigates the cultural significance of detritus.

In 1999, heralded by a small advertisement that read “Death Got You Down?,” a company called Investors Real Estate Development unveiled a memorial-park concept titled “Final Curtain.” More theme park than traditional cemetery, Final Curtain allowed the future deceased to design their own premature memorials, which ranged from a neon sign reading “Nick is Dead” to giant Etch-a-Sketches and Ant Farms that incorporated funereal ashes as their medium. Final Curtain was later revealed to be the latest conjuration of the notorious media hoaxist Joey Skaggs; as with any successful prank, it was initially received with certain genuflections of credulity.

Behind the risible veneer of Final Curtain was a tacit kernel of truth; i.e., that the “American way of death,” as Jessica Mitford called it, was becoming gradually liberated from its hoary reliance on marble headstones, lavish statuary, and carefully apportioned plots in increasingly dear neighborhoods. The leading economic indicator of this was the rate of cremation: From a mere 3.56% in 1963, to a projected 32.5% in 2010. This itself was also driven by economics—burial costs now account for less of the GDP than they did in 1960—and by social changes, such as the Vatican’s 1963 lifting of its prohibitions against cremation (having banned the practice in response to its adoption as an anticlerical practice in the wake of the French revolution).

With a rising turn toward cremation, there has been a certain rematerialization of death, a move away from fixed rites and territories of mourning—where marble and stone are the only tactile markers—and towards a condition where the remains of the dead, which now become the markers themselves, can be incorporated into a whole new array of ceremonies and objects. Where cremated remains, or “cremains,” in industry parlance, have for a long time mostly been stored in urns or scattered across specific places, there has recently emerged a panoply of novel end-uses for the ashes of the deceased. Eternal Reefs, for example, a Decatur, Georgia-based company that manufactures artificial reefs, will merge cremains with marine-grade, non-acidic concrete to create what it calls “reef balls,” vaguely wiffle-ball-like orbs whose spheres are intended to encourage the growth of coral. Those not content to sleep with the fishes can turn to Houston-based Celestis, which will launch a vial of ashes into stellar orbit for roughly a grand per ounce (Timothy Leary and Gene Roddenberry are among the company’s more famous clients). Those aiming for nearer atmospheres have incorporated cremains into everything from pyrotechnic displays (as His Dark Materials author Phillip Pullman did for his father-in-law) to paintings.

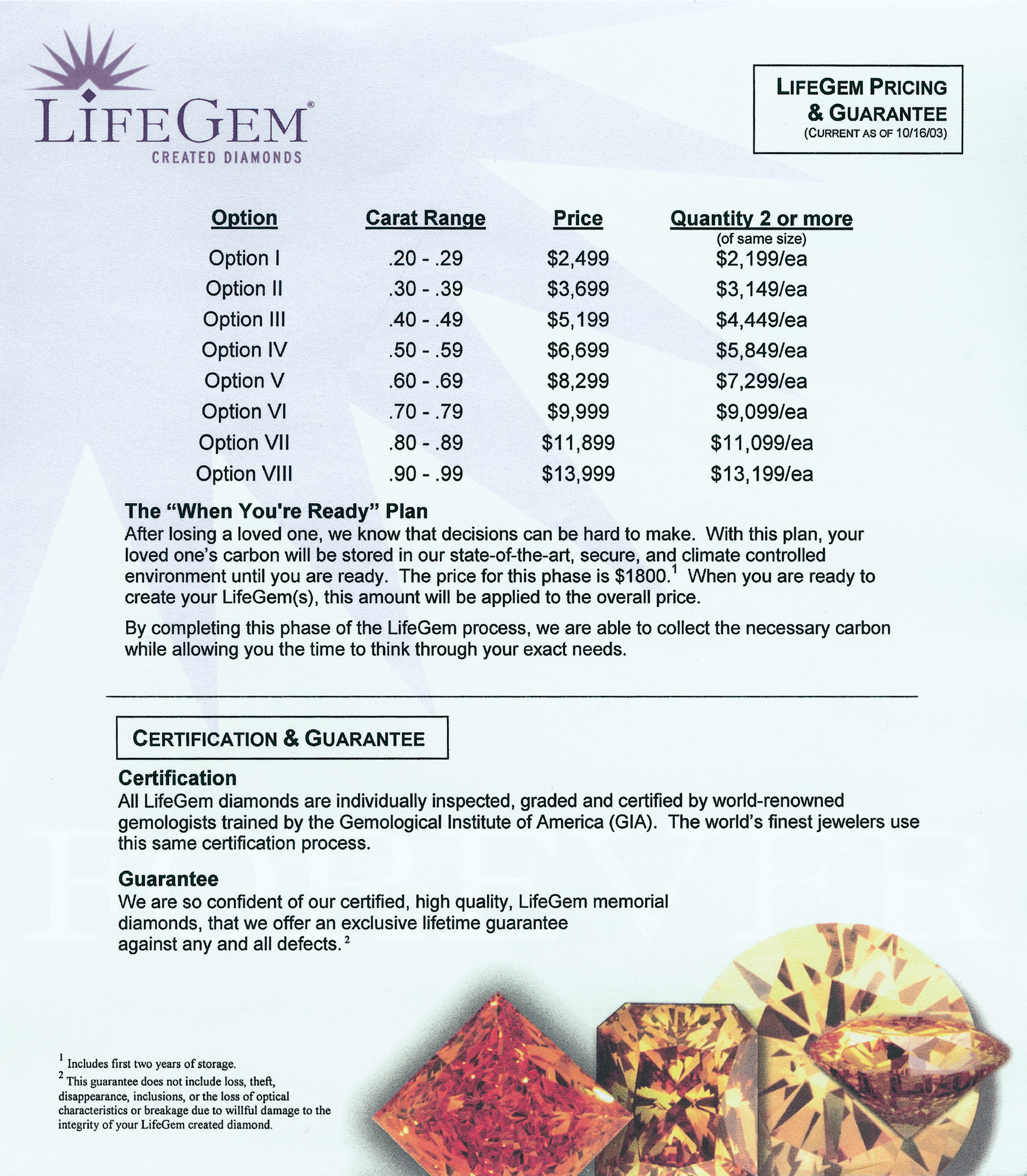

One of the most striking new forms, however, comes in a “memorial product” sold by the Illinois-based firm LifeGem. As the company describes it, “The patent pending LifeGem is a certified, high-quality diamond created from the carbon of a loved one as a memorial to their unique life.” Starting at roughly $4,000 for a quarter-carat (available in princess, round, or radiant cut), LifeGem will take a certain portion of cremains (usually about eight ounces, or a tenth of the total remains) that they have collected from a special cremation process in which oxygen levels are controlled to prevent the body’s carbon from coverting to carbon dioxide. The resultant black powder (“his dark materials”?) is then submitted to ultra-high temperatures in a vacuum, converting it to graphite; the graphite is then placed in autoclaves meant to mimic the convulsive pressures and temperatures by which diamonds are formed in nature. As LifeGem points out, “a diamond that takes millions of years to occur naturally can now be created from the carbon of your loved one in about eighteen weeks.”

The reader may note with some curiosity, and perhaps alarm, this strange convergence of two industries—each of which deals in its way with what might be termed the commodification of emotion—that have come under scrutiny for less than reputable business practices. At least since Mitford’s The American Way of Death, the funeral business has been regarded with skepticism, as operators endeavor to “upsell” bereaved (and thus vulnerable) patrons more elaborate means of burial than they can afford. Similarly, the diamond industry—a closely guarded cartel that artificially manipulates to its own financial end the available supply and distribution of diamonds (often obtained under dubious social circumstances)—works to “educate” consumers with a vocabulary of desirable cuts and has managed to insert itself into virtually every marriage ceremony of this century and the last (when it is not busy trying to craft new occasions for the purchase of diamonds by, say, single women); it now trots out the phrase “a diamond is forever” as if it were some ancient folk koan and not the sudden inspiration, one afternoon in 1947, of a copywriter for the N. W. Ayer advertising agency.

“Unlike men, diamonds linger,” sang Shirley Bassey in Diamonds Are Forever, in a line that takes on new meaning post-LifeGem (“Men are mere mortals,” she continued, “who are not worth going to your grave for.”) There is, of course, something entirely appropriate and perhaps poetic about the company’s viewable remains. For one, carbon is a primary component in the human body and the sole component of diamonds (coal, by contrast, is about 92% carbon). Carbon is what is known as an allotrope: meaning, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, that which is “susceptible to a change as to nutritive or physiological properties, without any change in physical or chemical characters.” Depending on its molecular structure, it can be diamond, graphite, or “fullerene,” named for the similarity of its molecular structure to the hexagonal “Buckyball” created by Buckminster Fuller; fullerene has been located in the burnt wicks of candles. Carbon is thus inextricably bound up with the cycle of life and death, and we might even say our lives are marked by a series of allotropic encounters with carbon: writing one’s name in graphite pencil on a piece of paper milled from a tree; burning leaves in the backyard; even taking one’s own life in a sealed garage with the car running. There has even been a movement afoot to replace traditional cremation techniques in which a wooden coffin is burned, as that releases carbon dioxide into the air, which denigrates the ozone layer and will someday be the death of us all.

One imagines a host of new and perhaps awkward social situations as LifeGems begin to become more prevalent. Will the earnest fiancé still achieve the desired romantic effect when he presents a ring that did not, as such things usually go, “belong to my grandmother,” but in fact is largely comprised of his grandmother? Will the diamond industry risk a backlash in declaring that LifeGems are not “real diamonds,” or perhaps could “real diamonds” conversely lose value as they come to be seen as cold, impersonal relics of a prehistoric volcanic flume reaching to the earth’s molten core, and not the shining eternal light of a dearly departed? Actually, though the technology of LifeGems is new, the idea behind it is not. In Victorian England, for example, “mourning jewelry” was a quite accepted, even revered, form of personal adornment; e.g., lockets that housed a strand of hair or even necklaces woven from the hair of the deceased. The fashion spread to nineteenth-century America, as in a letter-press advertising pamphlet from a hair braider in Athens, Georgia, titled Hair Braiding of Every Style and Pattern, which announced a particular specialty of bracelets, crosses, and necklaces fashioned from hair, including “special attention paid to interbraiding the hair of deceased friends into mementos and keepsakes, of any pattern desired.”

Perhaps the LifeGem, or any of the other novel cremains of the day, will actually help us, in their physical immediacy, get closer not only to the actual dead person but to the idea of death in general, moving us away from such palliative phrases as “loved ones” and “passed” (as in, “he passed”) and into more honest appreciations of the cycle of life and mortality. It may also provide the rather shocking contours of our materiality, our thingness that puts us on a molecular spectrum that includes living trees and dead hunks of coal. The LifeGem reminds us that we may be what we make of ourselves, but in death, it is from ourselves that things are made. As John Webster wrote in the Renaissance drama The Dutchess of Malfi, “Whether we fall by ambition, blood, or lust, Like Diamonds, we are cut with our own dust.”

Tom Vanderbilt lives in Brooklyn and writes for many magazines, including Wired, the London Review of Books, Smithsonian, and Artforum. He is author of Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America.