Fragments from a History of Ruin

Picking through the wreckage

Brian Dillon

For the eyes that have dwelt on the past, there is no thorough repair.

—George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss

1. For the Renaissance, the ruin was first of all a legible remnant, a repository of written knowledge. Classical ruins had preserved a certain stratum of the linguistic culture of Greece and Rome: the inscriptions on monuments, tombs, and stelae. Other mute objects—fragments of statuary, columns, bits of orphaned arch or broken pediment—composed in themselves a kind of script made of gesture, line, and ornament. In 1796, the French archaeologist Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy would ask, “What is the antique in Rome if not a great book whose pages have been destroyed or ripped out by time, it being left to modern research to fill in the blanks, to bridge the gaps?” But already, at the end of the fifteenth century, the rubble of the classical past had been figured as a sort of scattered cipher: a text that was alternately readable and utterly mysterious.

It happens most dramatically in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: the curious literary work attributed to one Francesco Colonna and first published in 1499. At the level of its language, the book is strange enough: it is written in a mélange of Greek, Latin, and Italian that led the critic Mario Praz to declare its author “the James Joyce of the Quattrocento.” Its narrative, however, is equally odd, and tells us a good deal about the conceptual proximity, in this period, of the architectural and the written enigma. The Poliphilo of the title travels in search of his lost love, and finds himself in a territory strewn with classical detritus: capitals, epistyles, cornices, friezes, kiosks, and pyramids; all, as he only dimly discerns, somehow significant. There are obelisks inscribed with hieroglyphics, linking the text to the long tradition of the emblem: the conjunction of word and image in which the reader is meant to divine a moral meaning. It is no accident that the emblem books of the following two centuries are full of such devices as disembodied hands, butchered torsos, and empty masks. Knowledge, so the emblematic ruin insists, is a matter of piecing together a sundered past.

2. In the eighteenth century, the ruin is an image both of natural disaster and of the catastrophes of human history. In fact, it is difficult to tell the two apart. The aesthetics of the sublime is in part an effort to name the confusion that comes over us when faced with wholesale destruction: we experience storms, battles, earthquakes, and revolutions as equally impressive facts of both nature and history. The text in which the universal significance of localized ruin is most elaborately dramatized is Les Ruines, ou Méditation sur les révolutions des empires, published in Paris in 1792 by the Comte de Volney. He begins: “Hail, solitary ruins! holy sepulchres and silent walls! you I invoke; to you I address my prayer. While your aspect averts, with secret terror, the vulgar regard, it excites in my heart the charm of delicious sentiments—sublime contemplations.” The author recounts his travels among the ruins of Egypt and Syria, before his eye ostensibly settles on a view of the Valley of the Sepulchres at Palymyra, where Volney had never been (all that follows is imagined on the basis of illustrations by the English archaeologist Robert Wood). Overcome by a “religious pensiveness,” he imagines the dead streets full of people, falls into a reverie on the cities of Babylon, Persepolis, and Jerusalem, and concludes, as he contemplates silted ports, fallen temples, and ransacked palaces, that the earth itself has become “a place of sepulchres.” Tears fill his eyes as he imagines contemporary France reduced to the same desuetude. A spectral figure now appears before him—the “genius of tombs and ruins”—and spirits him high into the air, from which lofty vantage he sees the globe spotted with deserts, fires, and “fugitive and desolate” peoples. It is a law of nature, Volney surmises, that all things must fall into ruin. But the apparition corrects him: the hideous earthly vision, above which he floats at a sublime distance, is not natural at all. It is, precisely, human history.

3. Romanticism turns the ruin into a symbol of all artistic creation; the literary or painted fragment is more highly prized than the finished or unified work. An aphorism by Friedrich Schlegel states: “Many works of the ancients have become fragments. Many works of the moderns are fragments at the time of their origin.” Everything tends towards the status of a torso: the incomplete or mutilated hunk of sculpted stone. The Romantic impulse is to valorize the very decay of the classical artifact. In 1779, the painter Henry Fuseli depicted The Artist Overwhelmed by the Grandeur of Antique Ruins: head in hands, he despairs at ever matching the splendor of the statues whose remnants are scattered around him in the form of a massive marble hand and a gargantuan foot. Even finished works are reimagined as mere fragments. For John Keats, the figures on a Grecian urn are frozen in time; they are both immortal and unfulfilled, “For ever panting and for ever young; / All breathing human passion far above.”

For Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, in his Laocoön, the classical sculpture represents not a narrative, nor even the frozen climax of a story, but a randomly chosen instant, a single moment that comes to stand for all that is missing. “The more we see,” writes Lessing, “the more we must be able to imagine. And the more we add in our imagination, the more we must think we see ... to present the utmost to the eye is to bind the wings of fancy and compel it, since it cannot soar above the impression made on the senses, to concern itself with weaker images, shunning the visible fullness already represented as a limit beyond which it cannot go.” This is the insight behind a poem like Coleridge’s Kubla Khan: the finished work is a short fragment of the text the poet claims originally to have imagined, before his opium-induced reverie was interrupted and he forgot two hundred lines.

The Romantic fragment differs from the earlier literary forms of the maxim, aphorism, and motto in this regard: it refuses to resolve itself into a discrete thought, polished witticism, or paradox among a collection of similar jeux d’esprit. The Pensées of Pascal are the tiles of a mosaic; the fragments of Romanticism—and later of Nietzsche, E. M. Cioran, Walter Benjamin—are like the same tesserae scattered as if by some cataclysmic eruption or invasion.

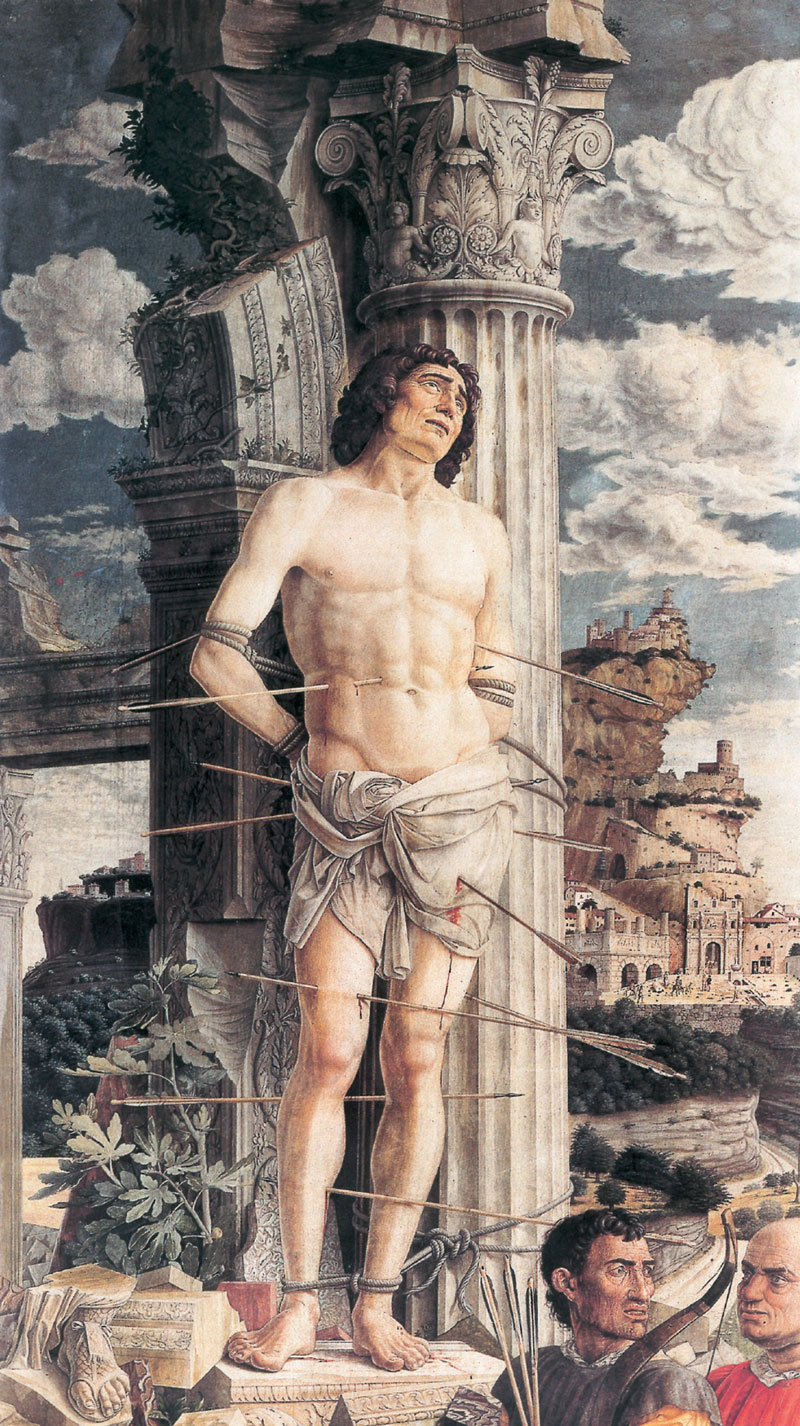

4. The ruin is made meaningful by the interposition, between object and viewer, of a frail human figure. In the art of the Renaissance, ruins appear first of all as a fractured ground or hinterland upon which to present the sacred or suffering body. In several cases, the Savior or saint in question (St. Jerome, for example, in a wilderness of toppled marble) is shown surrounded by the remains of a vanquished pagan world (which is also a reminder of the viewer’s own inevitable end). Less often, the Virgin is framed by a crumbling arch or tottering pillars. In Mantegna’s St. Sebastian (1480), a vast landscape of ruin opens out behind the perforated body of the martyr; in the foreground, where a pair of archers are about to vacate the scene, a single stone foot (all that remains of an adjacent statue) rhymes with the saint’s.

The history of ruins in art records the gradual diminution of the human figure until it is merely a tiny marker of the enormity of the destruction that has been wrought in the scene. In the seventeenth century, the figures shrink to take part in incidental anecdotes in the foreground, or at the edge, of the central drama of decay. Later, in the paintings of Hubert Robert, human beings clamber like infants among the ruins of ancient Rome, or form a thin frill of activity atop the Bastille, as they begin to raze it to the ground.

This dramatic shift in perspective—the insertion of the human as a scarcely visible vanishing point in the composition of disaster—occurs not long before another set of catastrophes is considered and pictured by geologists. In Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830–1833), the earth is revealed to have been “lacerated,” riven by scarcely imaginable forces. In the accompanying illustrations, the scale of the upheaval is conveyed by a series of minute figures, perched on the edges of volcanoes or precipices: intrepid tourists lured by the spectacle of destruction. The drawings are the geological equivalents of the Prisons of Piranesi. In 1822, Thomas De Quincey wrote of their endlessly ruined imaginary interiors: “Again elevate your eye, and a still more aerial flight of stairs is beheld: and again is poor Piranesi busy on his aspiring labors: and so on, until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall.” At last, it seems, the individual quite vanishes into darkness and decay.

The human figure reappears, however, within a few years, in the earliest photographs of ancient ruins. In Maxime du Camp’s photographs of the antiquities of Egypt, there is inevitably (sometimes tucked to the side of the structure in question, so as not to interrupt the composition unduly) the tiny punctuation mark of a local guide, giving some indication of the scale of the monument. But he is a reminder too—as also in the photographs of Édouard Denis Baldus, taken as part of the French state’s mission héliographique, that depict the Roman ruins of France—of the puny stature of the provincial population compared to the grandeur of the ancients (and by extension of the empire that even now is preserving that heritage for the future).

5. If ruination is in part a return to nature, in the nineteenth century nature itself is imagined as already ruined. In the writings of John Ruskin, for example, the natural world appears subject to an alarming erosion: its outlines have begun to blur, its forms to dissolve. Ruskin first bruits his distress at the apparent decomposition of landscape in 1856, in his Modern Painters. The modern landscape painting, he writes, is distinguished (or rather, not distinguished at all) by a certain loss of formal integrity: it has become smoky, cloudy, foggy, ignoble (in the sense, as one says of a gas, of having lost its “nobility,” its purity). The natural world has come to resemble, in fact, the murky atmosphere of the modern city, or of the industrial hinterland. Still, Ruskin does not definitively blame pollution from factories for the strange phenomenon that, in an essay of 1884, he claims has arrived in the skies above London: “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century.” This “plague-cloud,” says Ruskin, has haunted him since the 1870s. It looks, he claims, “partly as if it were made of poisonous smoke; very possibly it may be: there are at least two hundred furnace chimneys in a square of two miles on either side of me. But mere smoke would not blow to and fro in that wild way. It looks more to me as if it were made of dead men’s souls—such of them as are not yet gone where they have to go, and may be flitting hither and thither, doubting, themselves, of the fittest place for them. You know, if there are such things as souls, and if ever any of them haunt places where they have been hurt, there must be many above us, just now, displeased enough!” This last is a reference to the dead of the Franco-Prussian War. The passage looks forward, too, to a Europe whose landscape will have been more comprehensively devastated a quarter of a century later, and to another poetic response—T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, with its desperate motto: “these fragments I have shored against my ruin.”

6. In the dialectic between the ruin and nature, the ruin comes to be seen as natural; this is why it is possible to ruin a ruin. A particularly resonant example of a ruin ruined is the archaeological excavation, in 1874, of the Colosseum. In 1855, the English botanist Richard Deacon had published his Flora of the Colosseum, recording the 420 species of plant growing in the site that had been, until the construction of the Crystal Palace in London four years earlier, the largest architectural volume in the world. The six acres of flora included species so rare in Western Europe that their seeds must originally have been carried there, Deacon conjectured, by the animals imported from Asia and Africa for the city’s games and spectacles. These precious plants, he writes, “form a link in the memory, and teach us hopeful and soothing lessons, amid the sadness of bygone ages: and cold indeed must be the heart that does not respond to their silent appeal; for though without speech, they tell us of the regenerating power which animates the dust of mouldering greatness.” By 1870, the vegetation had all been stripped away, and a few years later the floor of the Colosseum was dug out to reveal the cellars and sewers. The area flooded, and the center of the Colosseum remained a lake for five years.

In his essay of 1911, “The Ruin,” the German sociologist Georg Simmel identified the precise relationship that had been disrupted in Rome. “Architecture,” he writes, “is the only art in which the great struggle between the will of the spirit and the necessity of nature issues into real peace, in which the soul in its upward striving and nature in its gravity are held in balance.” In the ruin, nature begins to have the upper hand: the "brute, downward-dragging, corroding, crumbling power" produces a new form, "entirely meaningful, comprehensible, differentiated." But at what point can nature be said to have been victorious in this battle between formal spirit and organic substance? The ruin is not the triumph of nature, but an intermediate moment, a fragile equilibrium between persistence and decay.

7. Where imagined future ruins were once the objects of metaphysical fancy or hubristic imperial dreams, the modern ruin is always, to some degree, a palpable, all-too-real remnant of the future. In 1830, having completed his architectural masterpiece, the Bank of England, Sir John Soane commissioned the artist Joseph Gandy to paint a series of views of the structure in ruins. Ten years later, Lord Macauley wrote of a future New Zealand tourist standing on a broken arch of London Bridge and contemplating, “in the midst of a vast solitude,” the ruinous dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral and a desolate city. (In the 1870s, Gustave Doré would imagine Macauley’s New Zealander perched by the banks of the Thames, sketchbook in hand.) The most ambitious projection of the future ruin, however, is that of Albert Speer, who claimed to have seen a concrete hangar, half-demolished, and been convinced that modern materials were unsuitable to picturesque decay: “It was inconceivable that a hunk of rusting metal could one day inspire heroic thoughts like the monuments of the past Hitler so admired. By using special materials, or by obeying certain laws of statics, one might be able to build structures which, after hundreds, or as we fondly believed, thousands of years, would more or less resemble our Roman models.”

The modern ruin—the industrial ruin, the defunct image of future leisure (the vacant mall or abandoned cinema), or the specter of Cold War dread—is in fact always, inevitably, a ruin of the future. And that future seems, retrospectively, to have taken over the entire twentieth century: all of its iconic ruins (Battersea Power Station in London, the atom-age archipelago that now stretches across America, the derelict environment of the former Soviet Union) now look like relics of lost futures, whether utopian or dystopian. For how long will the century gone by still look like it has some frail purchase on futurism? Modernist architecture, especially, seems reluctant to cede its franchise on the future: there is still a thrill of things to come to be felt among the ruins of the early part of the century, as if confirming the statement of Vladimir Nabokov’s that Robert Smithson was fond of quoting: “The future is but the obsolete in reverse.”

8. For all its allure, its mystery, its sublime significance, the ruin always totters on the edge of a certain species of kitsch. The pleasure of the ruin—the frisson of decay, distance, destruction—is both absolutely unique to the individual wreckage, and endlessly repeatable, like the postcard that is so often its tangible memento. The very recent, industrial ruin is the contemporary equivalent of the picturesque view of a decaying Roman amphitheatre: it is part of an aesthetic now so generalized as to have lost almost all of its charge as a generic image. The twentieth-century ruin has become the preserve of countless urban explorers and enthusiasts of decaying concrete: the evidence of their obsession is spreading across hundreds of websites devoted to haunted asylums, silent foundries, vacant bunkers, and amputated subway stations. The secret of these places, in short, is out: the motivation behind such a fascination for decay is less clear, however. The ruin, still with us after six centuries of obsession, is no longer the image of a lost knowledge, nor of the inevitable return of repressed nature, nor even of a simple nostalgia for modernity. Instead, it seems almost a means of mourning the loss of the aesthetic itself. Ruins show us again—just like the kitsch object—a world in which beauty (or sublimity) is sealed off, its derangement safely framed and endlessly repeatable. It is a melancholy world in which, as Adorno put it, “no recollection is possible any more, save by way of perdition; eternity appears, not as such, but diffracted through the most perishable.”

Brian Dillon is UK editor for Cabinet and the editor of the “Ruins” section of this issue. He is the author of In the Dark Room: A Journey in Memory (Penguin, 2005) and writes regularly on art, books and culture for Frieze, Modern Painters, the Financial Times, and the New Statesman. He lives in Canterbury.