Divine Wind: An Interview with Atsushi Takatsuka

Training to be a Kamikaze pilot

Ryo Manabe and Atsushi Takatsuka

On 25 October 1944, a group of Japanese airplanes flew out of a Philippine airfield: a few hours later, the mission was completed as all of them crashed suicidally into the US escort carrier St. Lo and several other naval vessels. This was the first official Kamikaze attack, organized as the last resort of the severely diminished Japanese military. A campaign of aggressive recruitment was conducted to fully mobilize the last and only resource with which Japan was left, namely fighters with a mentality of total self-sacrifice. The monumental honor of single-handedly sinking an enemy ship anesthetized the fear of death, and nearly 2,400 airplanes were said to have followed in the next ten months. However, the abrupt ending of the war in 1945 dismissed the remaining pool of the Kamikaze trainees to unexpectedly, and perhaps unwillingly, resume their ordinary lives in the shadow of once-accepted death. Atsushi Takatsuka, today a retired elementary school art teacher and a practicing painter, has put out a quarterly newsletter for more than twenty years. It has grown into an unprecedented compilation of thoroughly researched facts and hitherto unvoiced testimonies of the surviving Kamikaze pilots. Not only does Takatsuka’s newsletter help his fellow Kamikaze trainees cope with the stigma of not completing their missions, but also provides a counterpoint to both the wartime glorification of and post-war repugnance toward the Kamikaze program. Ryo Manabe met Takatsuka in Tokyo to discuss the historical profile as well as sociological implications of the notorious operation.

Cabinet: Let’s start with the definition. What is Kamikaze?

Atsushi Takatsuka: Kamikaze is shorthand for “Kamikaze Special Attack Force” [”Special Attack” being an euphemism for suicide missions]. The phrase “Kami-Kaze” [Divine Wind] was derived from the late-thirteenth-century incident in which phenomenal typhoons saved Japan from the Mongols.[1] As far as suicide missions are concerned, there were non-aviation units as well: the “Kaiten” [Revolving Heaven] unit, which was also referred to as “Human Torpedo”; the submarine units “Kouryu” [Biting Dragon] and “Kairyu” [Sea Dragon]; the motorboat-based “Shinyo” [Shaking Ocean] unit, etc. As you can see, none of these is technically “Kamikaze,” although the distinction is blurred nowadays. The first group of crash-dive airplanes with the officially given name of Kamikaze flew out on the 25th of October 1944, and the Kamikaze was dismantled at the end of the war in August of 1945, so in all it lasted only for about ten months. At the earlier stage of the Kamikaze tactics, which is to say the beginning of the Philippines Campaign, the Kamikaze unit consisted only of selected pilots who had completed the official flight training. However, in the latter phase of the campaign, they appointed even those who were still in the middle of training as Kamikaze candidates. And, by the way, there was a difference between a Kamikaze pilot and a candidate for Kamikaze missions: only immediately prior to an actual sortie did the military issue the ceremonial announcement by which a candidate became a Kamikaze proper. So sometimes people call me an “ex-Kamikaze pilot” or a “survivor of Kamikaze squadrons,” but these are contradictory by definition: becoming a Kamikaze inevitably entailed death.

What was the historical context of the Kamikaze tactics?

In the year prior to the end of the war, the number of lost battles was swiftly mounting. This prompted young Japanese officers to confidentially propose various last-resort options to the military council. The Kamikaze strategy was one of them, without being an order handed down by the military authorities.[2] For instance, the idea of Kaiten, the suicide torpedo, was conceived as a way to utilize excess torpedoes. The Japanese torpedoes were technically advanced and the Navy was invested in the production. However, as Japan lost more and more battleships, opportunities for launching these torpedoes dramatically decreased. As a result, a number of torpedoes were left unused and piled up in warehouses until they were given a second chance as suicide weapons. Kaiten was a manned torpedo loaded with 1,500 kilos of high explosives, which is more than twice as much as conventional torpedoes. To target enemies and accurately conduct bodily attacks on them, a special periscope was devised. As soon as an enemy vessel was spotted and its location confirmed, Kaiten pilots would climb into the torpedoes, measure the distance and angle, and be launched from their carrier submarine. Once separated, even in a case of unsuccessful attempt, a Kaiten was given no choice but self-destruction in order to maintain the confidentiality of the weapon. This made it possible for the crew of the carrier submarines to determine whether a Kaiten attack was successful or not, by judging the timing of the explosion heard in relation to that of launching.

It was around the same time that the aviation Special Attack weapon, “Ohka” [Cherry Blossom], was invented. It was a heavy glider with 1,200 kilos of explosives loaded in its nose. An Ohka would be carried above an enemy vessel by a mother airplane and released when the target was confirmed. It traded the basic functionalities of an airplane such as maneuverability and speed for the greater impact of an explosive that was beyond the craft’s normal loading capacity. But the Ohka shared the same idea of vehicle-weapon hybrid with the Kaiten, and in fact with most of the other Special Attack inventions. When the war situation further worsened and the number of surviving fighter jets dropped, patrol jets and even outdated models that had been used only for training were mobilized for the Kamikaze missions. The Ohka eventually came to be utilized for most of the Special Attack missions after the Okinawa Campaign, since, despite their lack of speed, their compact bodies were ideal for flying out of small hidden airports constructed on dry riverbeds or golf courses, and for weaving in and out of mountains at night.

How did individual Kamikaze candidates get selected? Were there any limitations applied?

In the earlier stage of the Kamikaze operation, the Japanese Navy could afford a democratic process of selection. For instance, the first twenty-four Kamikaze pilots were asked by their commander, and none declined his request. When the unexpected recruitment of the Kaiten was announced in my Naval Primary Aviation Course, everyone but the students and a few commanders were ordered to leave. In this highly confidential and intense atmosphere, four-inch square slips were passed around, and five minutes were given to make the decisions: those who wished to switch to the submarine unit were told to put a double circle, those who would leave the decision to their commanders a single circle, and those who only wanted the initial flight career were to leave it blank. In this specific case, there were a few limitations. For instance, oldest sons and only children were excluded due to the concerns for their family structures. Since this particular recruitment was for submarine unit, those who were not skilled in swimming and those who were susceptible to seasickness were disqualified. Generally speaking, the physically fit and relatively older (seventeen and over) ones were preferred. Given these criteria, it is said that roughly one-tenth of the applicants were accepted in this recruitment. Shortly after, they were transferred to other training bases that were specific to the Kaiten troops. All this, however, was forced to change dramatically by the spring of 1945. The Secondary Aviation Course was discontinued in order to speed up the transition from the foundational education to the practical training, and the focus of the practical training shifted to the Kamikaze flight itself. The draft became less selective and less voluntary.

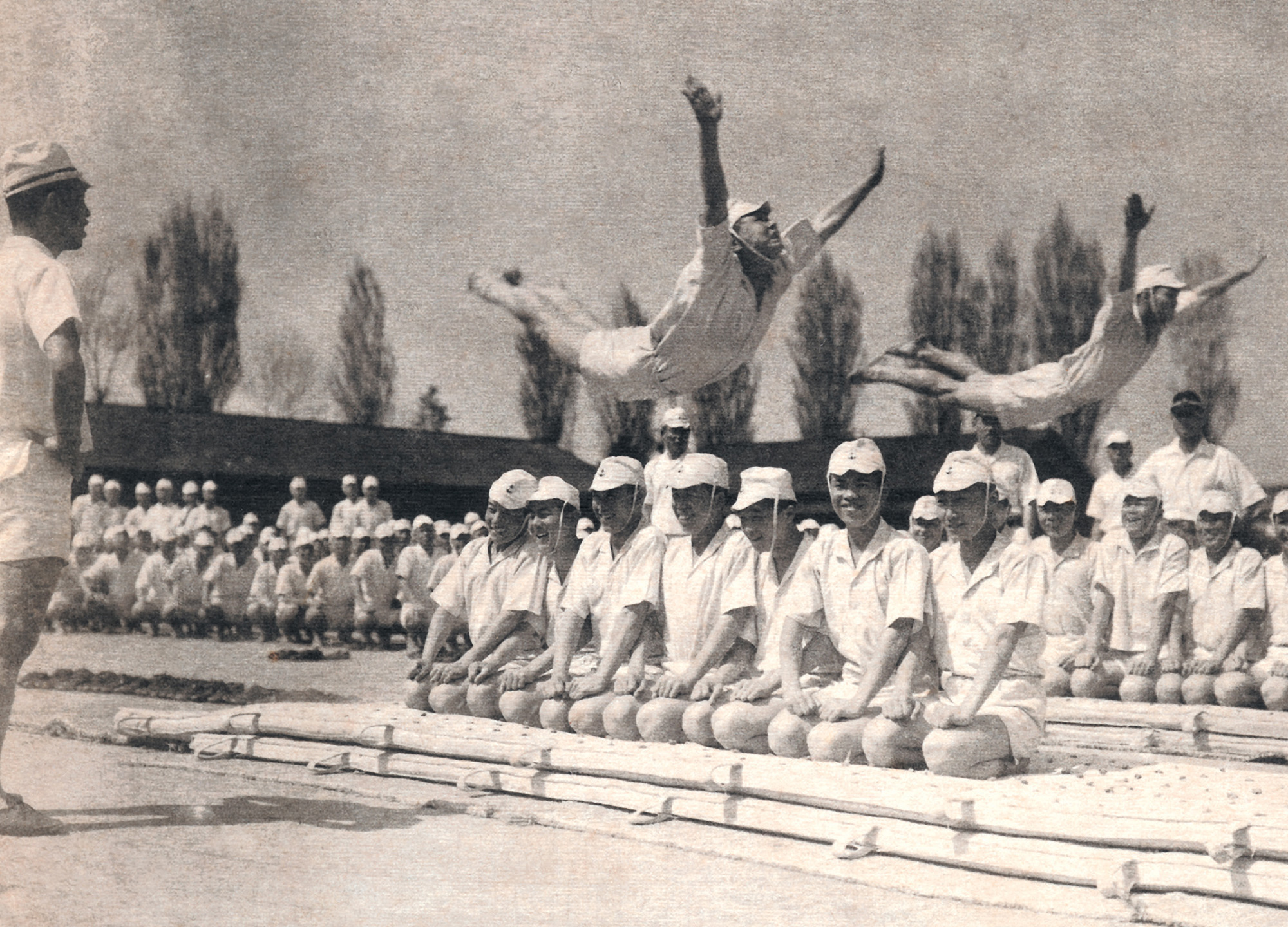

What kind of special training was required for the Kamikaze pilots?

Kamikaze attack may sound easy when described merely as a suicidal dive at an enemy. In fact, there was a rumor after the war that even those who did not know exactly how to fly an airplane were appointed for the Kamikaze missions. But there was a specialized training menu for the Kamikaze pilots because, for instance, they needed to be capable of steering the airplanes under extreme gravity when detached from mother carrier aircrafts. Other examples are launching from catapults built on mountaintops and high-altitude flight on newly invented rocket-engine airplanes.

How much damage from the Kamikaze attacks was reported? Besides physical destruction, was symbolic damage also taken into account?

Even today, exact figures are hard to obtain, but according to one report, which is supposed to have matched the American sources, 2,370 Kamikaze planes flew out of the military bases, half of which were confirmed as crash-dived. As a result, 203 ships of the Allied Forces were damaged, 83 of which sank. The damage brought about by the Kaiten unit is still unknown. As for the Shinyo unit, there were only one or two attacks reported to be successful in the Philippines, and only one in Okinawa. Needless to say, gathering and delivering information was extremely difficult during the war, so even the military authorities had no more than a vague idea of how successful the Kamikaze operation would turn out to be. Symbolic damage may have been expected, but personally, I never thought about how threatening I might be to the enemy. I was preoccupied with whether or not I could successfully carry out the mission when the time came.

What about the psychological effects on the Japanese side? I assume the Kamikaze strategy fueled patriotism and inspired a sacrificial mentality.

Well, as a whole military community, I am not sure if we were in good enough shape to put the Kamikaze operation in such a perspective, although there were flyers and posters on the street saying, “All One Hundred Million Suicide Attacks,” or “Move Forward, One Hundred Million! You Are Fireballs.” So I would say that Japan certainly had an ideological momentum in which each member of the nation was encouraged to look up to the suicide-attack soldiers and do his or her absolute best for the country.

Did the government promise any type of tangible compensation to the Kamikaze pilots?

Compared to deaths in regular duties, fallen soldiers in the suicide missions were entitled to exceptional posthumous promotions. For example, four-rank promotion would be given to a Private after his death, allowing him to skip the rank of the officer and advance to Second Lieutenant. This was not only to honor his completion of a suicide mission, but it also affected the amount of pension his family would receive after the war. However, in terms of the motivation for volunteering for Special Attack missions, these forms of tangible compensation were secondary: what came first was a desire for recognition in a strictly hierarchical and highly competitive community. We all experienced an enormous sense of superiority when we were called to serve as Kamikaze candidates, leaving the rest of the group behind. As you can imagine, seventeen or eighteen is generally a time when boys get most competitive, you know? I would say this competitive nature of the youngsters, who comprised a major portion of the Special Attack Force, fueled the suicide operation more than anything.

Securing a certain number of pilots must have been crucial to the administration of the Kamikaze force. Did the government devise any strategic advertisements?

Aviation was the department that needed the most reinforcement, and in order to supply more pilots, recruitment for the Primary Aviation Course got more aggressive than in previous years. The most immediate change was that they suddenly started talking about this foundation course differently: what used to be a place for dropouts, who were not good enough for the elitist Imperial Naval Academy, was transformed overnight into a decent career choice. But since the number of candidates they acquired did not quite match their expectations, the military authority put pressure on prefecture-level administrators to have each school provide a required number of candidates. The consequence was evident in the size of Class 13 of the Primary Aviation Course to which I belonged: there were 28,000 of us, which is nearly ten times more than the previous class. However, ironically enough, they were confronted with another problem: the number of training facilities and airplanes fell far short of what was needed for that many trainees. I think this was the reason why redesignation of soldiers for marine/submarine suicide units was arranged. Compared to the suicide airplanes, the marine weapons were more easily manufactured and mastered. Nevertheless, the recruitment continued to be uncompromising until the very end of war, for there was nothing else available to keep their hopes high given the worsening situation with the war. It finally reached a point where a troop called “Fukuryu” [Hidden Dragon] was organized: wearing simple scuba gear, they hid under water along the coast and blew up the landing crafts that passed above them using bamboo sticks with explosives attached to the tips. Another unit, called “Doryu” [Earth Dragon], specialized in suicide attacks on enemy tanks: they would crawl out of pits with bombs strapped to their bodies and explode right under the tanks.

As is clear in the examples you have already given us, the unusual nature of suicide missions suggests that the designs of the vehicles were equally unusual.

Yes, the basic idea behind the Kamikaze tactics is that everything is disposable. Therefore, the designs of the vehicles were simple enough for mass production.

I recall “Shinyo” was simply a wooden boat with a used Toyota motor attached and loaded with as much explosives as it could physically bear.

Right. As much as 250 kilos of explosives was loaded on one boat. It was true with the Ohka, also. The parts that did not require much structural strength were all made of wood.

When it came to war technology, the Germans were mentors to the Japanese. Were the designs of the Kamikaze vehicles influenced by the Germans?

Certainly Japan had an established relationship with the Germans at the time, but it was difficult to maintain communication. For instance, a blueprint for “Shusui,” Japan’s first rocket-engine jet, was lost while being transported from Germany because the submarine was destroyed. So the prototype for Shusui was built based on the memories of the surviving officers.

By definition, the Kamikaze mission is one-way. In preparing for the final flight, were there standard rituals such as prayers, songs, dances, or drugs? Was the last meal any different?

No, as far as I know, we did not have any procedure that was particularly formatted. I have heard that some people buried locks of hair in the backyard of a shrine, and others took alcohol to reduce their stress, but this was not required nor recommended by the officers. They just told us to leave a will if we wanted, and some of us did leave final statements in the form of poetry, but the style of mental preparation was principally up to the individual. I wouldn’t say the length of military career made no difference in this process of self-control, but by and large, the Kamikaze candidates had already accepted their imminent deaths by the time they had completed the basic training. Besides, I think the sense of attachment to life itself was numbed. In some troops, though, it was a custom that those who had their final sortie scheduled were entitled to a few days of vacation and given permission to visit home.

Wasn’t it a concern that sending the pilots home might affect their determination?

No. Remember that love for your family and love for your country perfectly coincided with each other during the war.

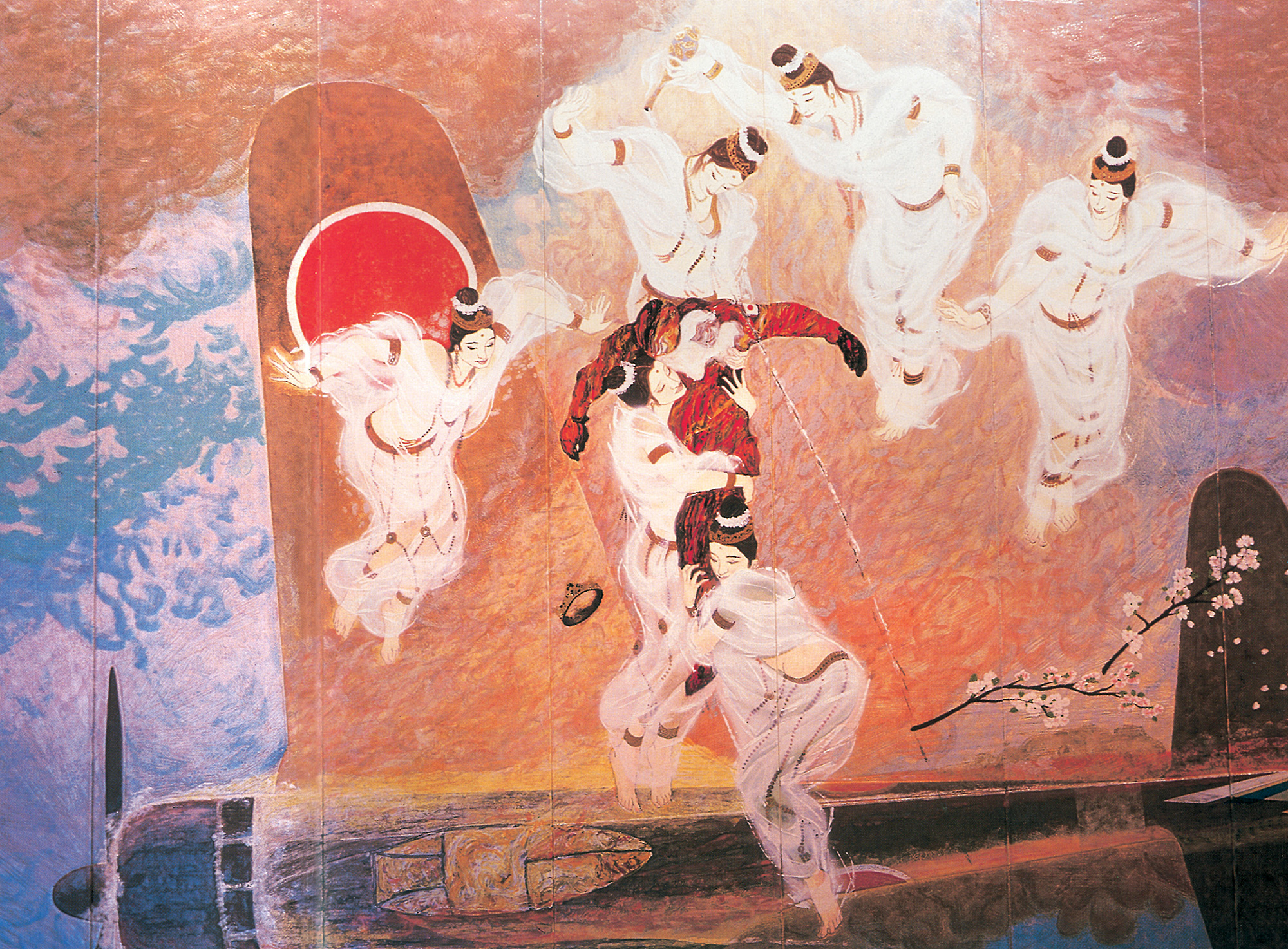

In your book Yokaren [The Foundation Course], I noticed that the icon of the cherry blossom appears repeatedly. Although it is a popular icon in Japanese literature and poetry throughout history, its omnipresence in the war context was rather surprising. The term “cherry blossom” is integrated into the title of a war anthem and into the name of a troop and a fighter plane. There was even a war medal in the shape of a cherry blossom. How would you read the relationships between the Japanese, the cherry blossom, and the Kamikaze mentality?

I think the cherry blossom symbolizes a sense of detachment from life that is characteristic of the Japanese aesthetic. Cherry blossoms are simple, transient, and seem to willingly accept their fate in perishing.[3] To praise such simplicity and impermanence is a uniquely Japanese aesthetic, which I think is fair to reference when we think of why the Kamikaze operation was met with such minimal resistance.[4]

How do you and other Kamikaze candidates who never had a chance to complete your missions feel about those who did fly?

I have posed that question to numerous ex-Kamikaze pilots whom I have come to know through the newsletter I publish, and the response varies from person to person. Some survivors literally owe their lives to those who flew, since the rule was that in case of sickness or injury, you would be replaced by another pilot who was next in line. So they must have suffered from indescribable feelings to this day. But the bottom line is that it was inevitable. All of us shared the same vision of the suicide mission being our fate, and as individuals, we had no power over the decision of ending the war either. Many of us continue to attend memorial services and recognize the distinguished accomplishment of fellow aviators, but I think those occasions also give us opportunities for sharing the inexplicable resentment and ill feelings that we normally suppress. To me, what has been more excruciating than anything is the fact that my life was forced to dramatically change twice in only two years, regardless of my will. The first was to have been carried away by the decision our school made in response to the prefecture-level recruitment, which was that everyone must volunteer to serve in the military. Before, I had never imagined myself being a serviceman. The second is to have survived rather accidentally despite my acceptance of and resignation to death.

When you first saw the news on September 11, did you make a connection to the Kamikaze?

I had never even thought about the connection between terrorism and the Kamikaze operation until someone pointed it out to me. Then I thought, “How could they possibly be thought of as in any way being related when one is a non-discriminatory attack on citizens and the other is a military strategy targeting battleships!” Also, they are completely different in terms of their technical and procedural aspects. But after a while, they started to present some similarities: the Kamikaze and the terrorist attacks on 9/11 were both belief-based acts of self-destruction, for example. Our Emperor used to be referred to as a human deity, and worshipped as such.

Did the Kamikaze pilots have clear images of the world to come after the completion of their missions? It was said that the 9/11 terrorists believed a very concrete scenario: after the mission they would enter heaven where virgins would be waiting for them, and so on.

In a popular war anthem at the time called Douki no Sakura [Cherry Blossom of Comrades], there was a line: “At the floral capital of Yasukuni Shrine, we will bloom on the spring treetops to see each other.” I do not think we necessarily had a concrete image of the Yasukuni Shrine, but we vaguely thought that after our deaths we would be enshrined and get to see our comrades who had died before us.[5]

Can you think of any myths involving the Kamikaze? Have you encountered outrageous rumors and absurd misperceptions?

If I come across the word Kamikaze used synonymously with “reckless and insane,” I certainly cannot help feeling uncomfortable. At the same time, though, I don’t think we have made conscious efforts to correct this kind of misinterpretation. For years, many of us hid the fact that we were involved in Kamikaze because the post-imperialist society of Japan quickly developed an antagonistic stance against anything or anyone that was associated with the word Kamikaze. In fact, it sometimes caused trouble when we applied to schools and jobs after the war. There was a term “Special Attack Syndrome,” which referred to a state in which an ex-member of the Special Attack Force was devastated from the missed opportunity of dying in honor, and yet not able to find an alternative aspiration in life. In my case, looking at the increasingly darkened series of paintings that I started after the war, I finally realized that my memory of Kamikaze was fermenting. That was when I started my research in order to obtain the entire picture of the thing, which was followed by the process of writing. As for my painting, it has still continued to address the theme of “distance,” a kind of tension between two non-objects.

What prompted you to launch your newsletter?

It has been nearly twenty years, but I consider it a continuation of the book Yokaren because it inherits the original purpose of identifying what felt like murk lying on the bottom of my heart. It has been widely supported by my generation, those who share the same emotional complications, and recently, I have become motivated to enlighten younger generations about the war through this newsletter.

- In 1264 and 1281, Mongol emperor Kublai Khan, grandson of the great Genghis Khan, made determined attempts to conquer Japan with massive fleets. Both times, Japan was unprepared to repel such overwhelming and technically advanced military forces, but miraculously timely typhoons destroyed a significant portion of Mongol fleets, forcing them to retreat after just a few days of fighting. These heaven-sent typhoons were later hailed as answers to Japan’s prayer and became known as Kamikaze, or “Divine Wind.” See Robert Leckie, Okinawa: The Last Battle of World War II (New York: Penguin Books, 1995).

- It was Admiral Takijiro Onishi who inaugurated Kamikaze tactics when he arrived in the Philippines in mid-October 1944. His statement made in October 1944 reads: “Once we make the decision to use body-crash tactics, we are sure to win the war. Numerical inferiority will disappear before body-crash operations.” See Albert Axell & Hideaki Kase, Kamikaze: Japan’s Suicide Gods (London: Pearson Education, 2002), p. 36.

- Inazo Nitobe’s classic text, Bushido: The Soul of Japan, offers an interesting comparison between the Japanese cherry blossom and the Western rose: “We cannot share the admiration of the Europeans for their roses, which lack the simplicity of our flower. Then, too, the thorns that are hidden beneath the sweetness of the rose, the tenacity with which she clings to life, as though loathe or afraid to die rather than drop untimely, preferring to rot on her stem; her showy colors and heavy odors—all these are traits so unlike our flower, which carries no dagger or poison under its beauty, which is ever ready to depart life at the call of nature, whose colors are never gorgeous, and whose light fragrance never palls.” See Inazo Nitobe, Bushido: The Soul of Japan (Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1969), p. 113.

- During the war, the verb “Chiru” (literally translated as “scatter”) was often used as a euphemism for dying in suicide missions. This illustrates the poetic notion of the suicide mission: it is as natural and inevitable as flower petals scattering in the air.

- The Yasukuni Shrine (“Peaceful Country” Shrine) in Tokyo was built in 1868 as the guardian shrine of Japan, where fallen servicemen were believed to join the guardian spirits of the nation. It was the only shrine in the country that the Emperor himself visited twice a year to show his respect; being enshrined at Yasukuni was therefore considered a special honor. The post-war Yasukuni, however, has been increasingly a target of criticism, especially in Asian countries, since its glorification extends to controversial figures like General Hideki Tojo, Japan’s most prominent war criminal. See Axell & Kase, pp. 12–18.

Ryo Manabe is senior assistant editor of Cabinet.

Atsushi Takatsuka is the author of Yokaren (Hara Publishing House, 1972) and the editor of 13, a newsletter about the experiences of Japanese pilots who trained for kamikaze missions.