Stripes

Belly up to the bars

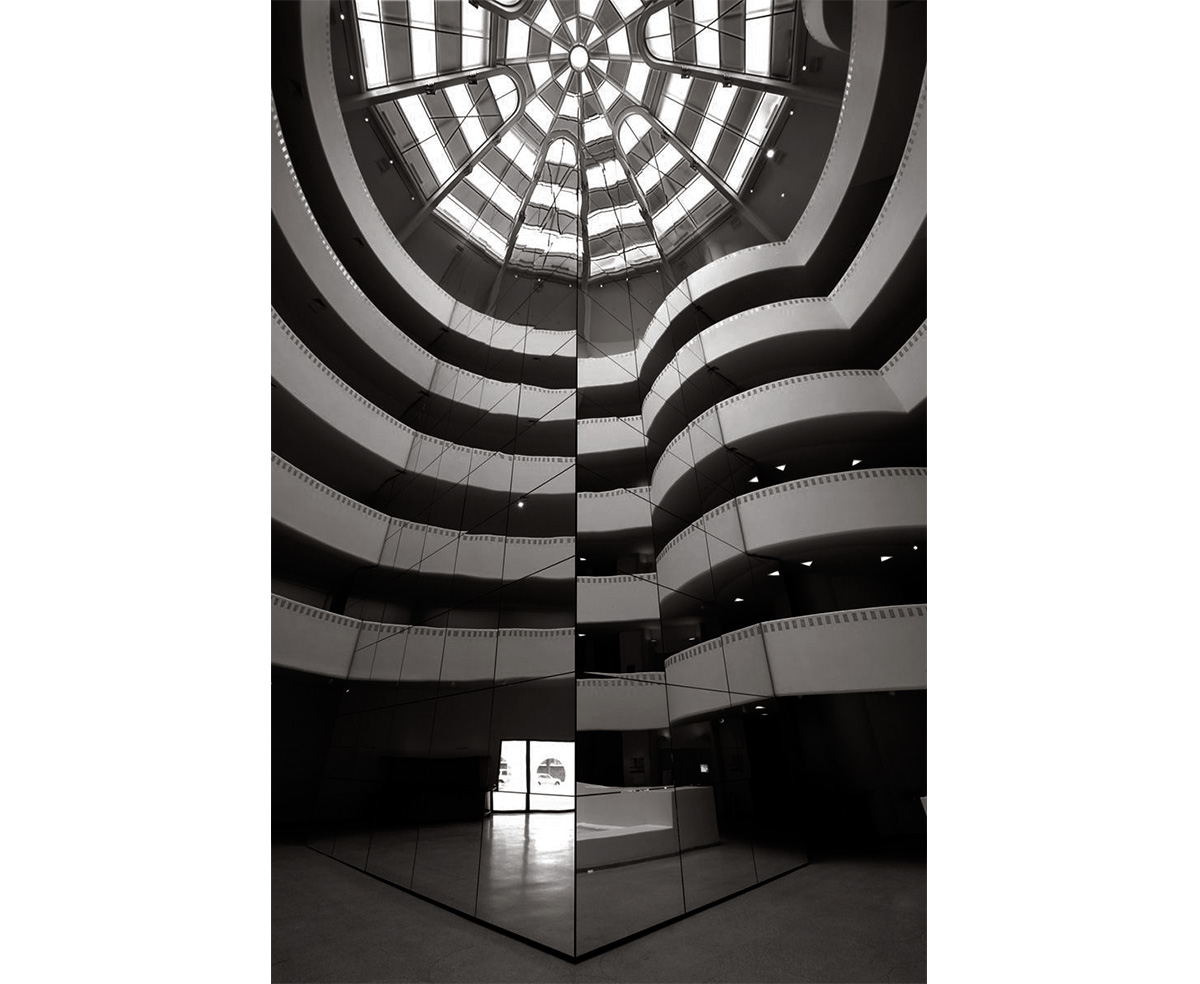

Implicasphere

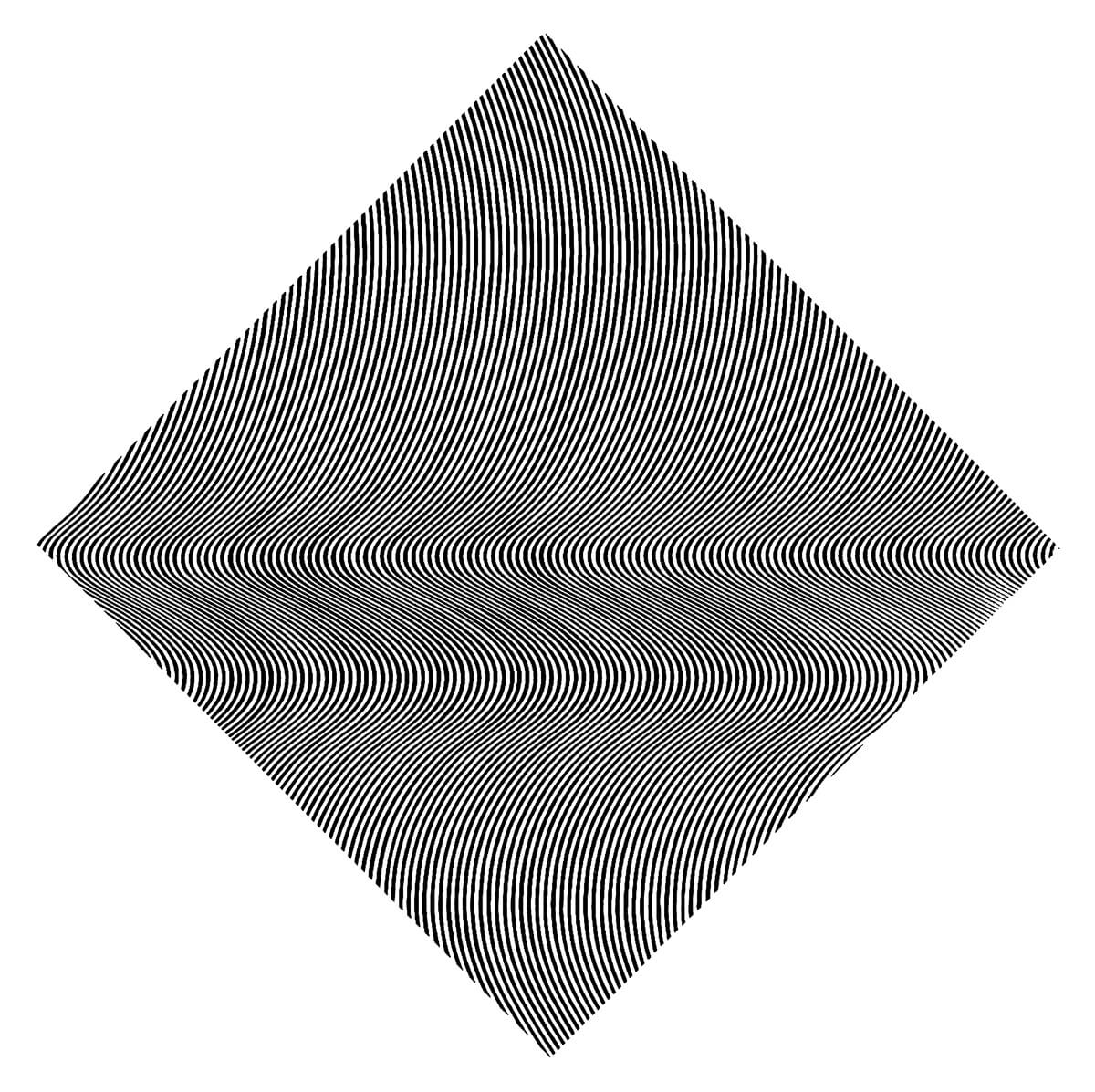

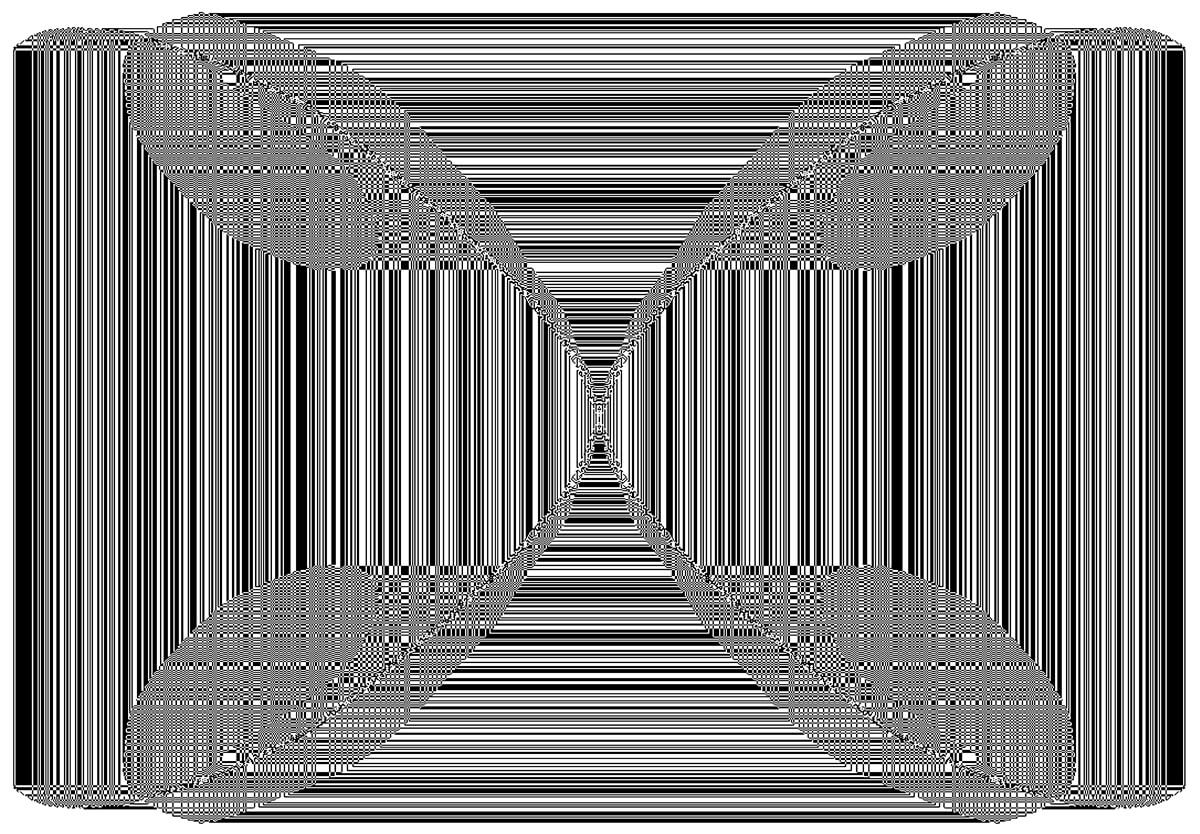

Stripes appear bold, strident even, wearing their intentions on their sleeve. And yet they are sly shape-shifters that trick the eye. They can camouflage or make ultravisible, give sculptural dimension to flat surfaces, appear to break up objects into new shapes, and reduce or expand their bearer. The Implicasphere project is an attempt to find the edges of an apparently ordinary word, to lasso an elastic cordon round the limits of where it stops being itself. But we have found stripes to be a particularly vacillating subject with no real beginning or end.

First, what’s the difference between a line and a stripe? It’s not simply a case of number, since stripes can be singular. All lines are rectangles of sorts and so share what would seem to dominate the formal character of the stripe. Yet, while the space a line crosses is not part of it, the space beside the stripe is both its counterpart and its contrast, its negative and brother. The stripe, we discover, is an optical “on” and “off” field that at once affirms and contradicts itself; it is also what it is not. In patterns of different color, tone and size of stripe, this multivalence can be eye-bogglingly complex.

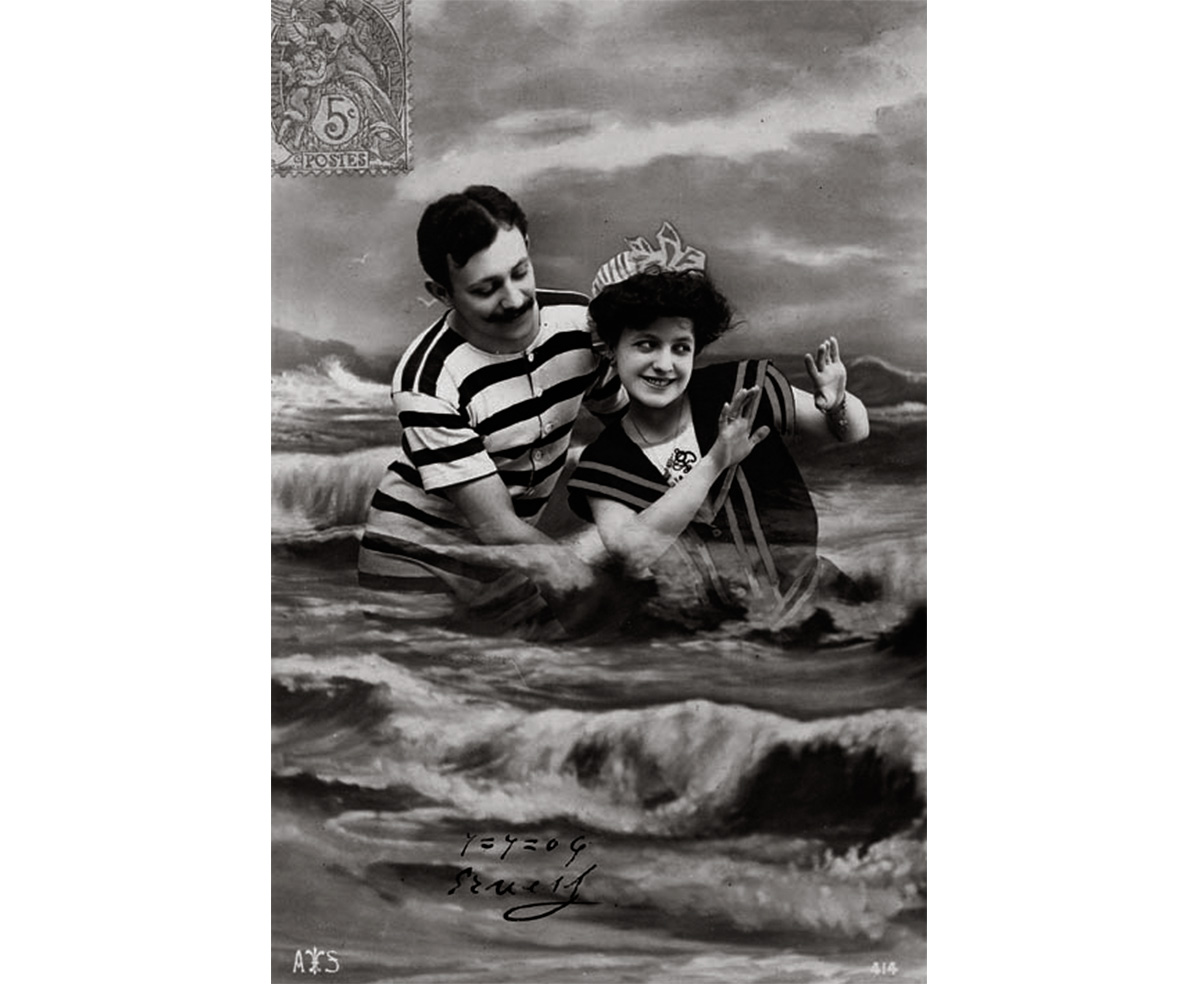

Does the stripe have innate significance? As a stigmatic motif, stripes are projected across novels and films. The slats of the louvered blinds through which we seem to read Alain Robbe-Grillet’s La Jalousie amplify its elicit atmosphere, the protagonist’s phobia of stripes in Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound is almost surgical in its insistence, and the bar-like shadows that fall across Walter Neff in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity are a premonition of a man destined for jail. Whether they traditionally signify the social outsider (on the clothes of prisoners, butchers, barber-surgeons, the Wicked Witch of the West, and the wretched bearer of the poo-stripe) or the happily exceptional and flamboyant (the circus tent and the carnival clown), across Western history stripes mark out difference. Yet, in complete contrast, they can transform a man into an insider in the uniform of the old school tie, pinstripe suit, rugby shirt, national flag, and the sleeve of the soldier or scout who has earned his stripes. In product design, stripes are a fanfare to speed, shipshape efficiency, and cleanliness: racing stripes psychologically soup up an old banger, while the chewy white squares of Pacers, a popular British confection of the 1970s and 1980s, were shot through with minty green stripes like toothpaste to hint ironically at dental health. So, it seems that both the conceptual and social character of stripes is one of contradiction and transformation.

Stripes of all stripes are manifest on every scale. The globe is wrapped in Walt Whitman’s “long river-stripes” and infested with barcodes; the inner ear contains a tiny “Hensen’s stripe” and the DNA chemistry of the body is unraveled in stripe coding. Nature seems to perpetually organize itself into stripes: the electromagnetic spectrum, thumbprints, ripples in sand, leaf markings, striated rock. Or, like the cheetah whose retina is arranged in a streak oriented to the horizon, is it rather that we perpetually read the world through the filter of the stripe?

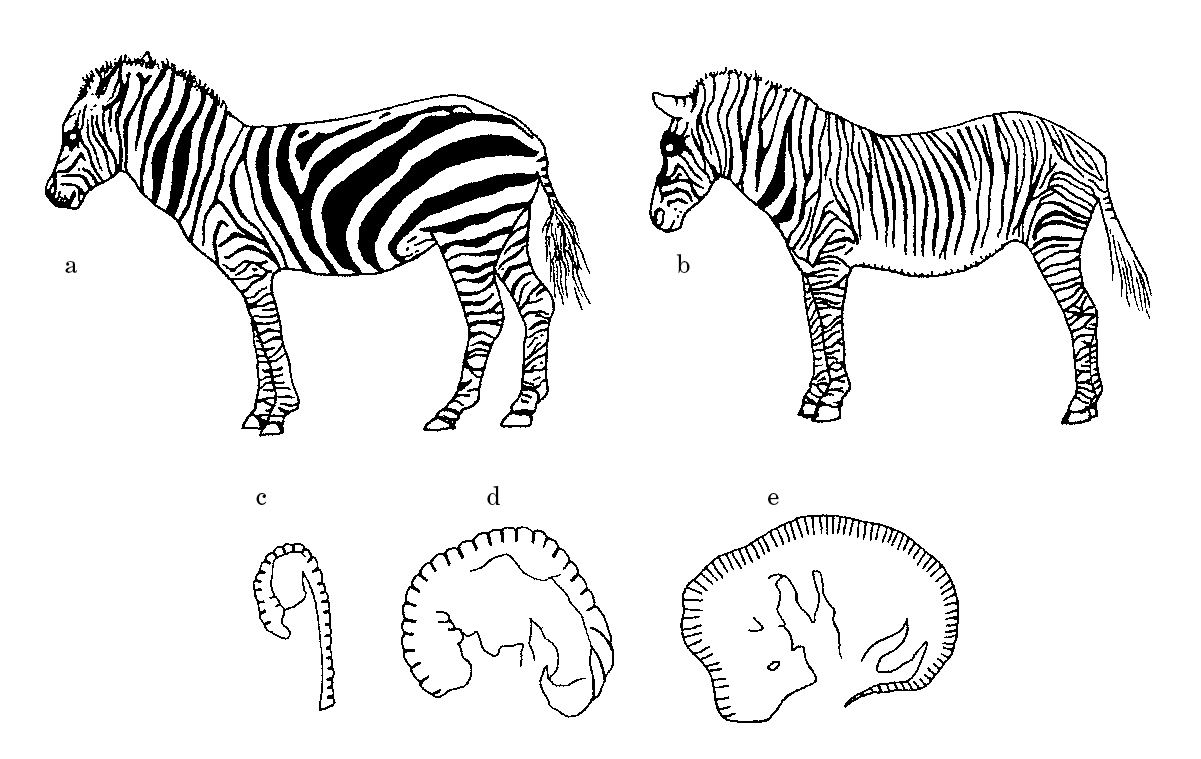

If indeed the markings of the adult animal are laid down by a chemical pre-pattern in the very young embryo, the timing of this pre-patterning stage can be crucial, since the size and shape of the embryo changes fast. This fact may be reflected in the differing stripe markings of the zebras Equus burchelli and Equus grevyi: the stripes of the former are broader and less numerous than the latter. The same chemical mechanism, producing stripes of the same width, would then give the smaller Equus burchelli embryo (Fig. c) fewer stripes than the larger Equus grevyi (Fig. e). So, when both have grown to a comparable size, the former has broader stripes than the latter.

I should add a cautionary note here: stripes are in fact not all that easy to make in Turing-type models, since they have a tendency to break up into spots. Murray assumed that stripes could survive in his model, but in practice extra ingredients are commonly needed to ensure this. For example, stripes may be stabilized if there is an upper limit to the rate of autocatalytic production of the activator, so that this reaction can become “saturated.”

Murray ventured to look at the patterns that would be generated by reaction–diffusion systems in more complicated geometries, such as the junction of the leg and body of a zebra. Here the same kind of modification of the stripe pattern is seen in all zebras—a kind of chevron pattern in which the bands of the leg blend with the stripes of the body. These markings are called scapular stripes. … Murray considered a simplified two-dimensional approximation to the shape of the leg-body junction, and found that a system that generated stripes in the body and bands in the leg would also produce the chevron pattern at the junction. …

So, within Murray’s model, if the chemical parameters in the reaction–diffusion system are much the same for all species (an assumption that is not unreasonable but not firmly supported either), then the size and shape of the embryo at the time of pre-patterning exert a dominant influence on the eventual pattern. One implication is that small animals with short gestation periods should have less complex patterns than larger animals, because their smaller embryos support fewer modes. On the whole this seems to be borne out, perhaps most dramatically by the honey badger and the Valais goat, which exemplify the simplest kind of non-uniform coloration of all: an abrupt division into a white and a black half.

—Philip Ball, The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

And if any mischief follows, then thou shalt give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe.

—Exodus 21:23.

Who puts the stripes on humbugs?

Who puts the pips in jam?

Who puts the coco in coco-nuts?

Tell me, if you can.

—B. Dooley, Who Put the Stripes on Humbugs? (London: Peter Derek, 1937).

Spots are like stripes in making evident and emphatic the difference between what is socially approved or included and what is disapproved or outlawed. But the fact that the area of intersection of spots and stripes is so extensive can also disclose some striking differences between them. The point of the stripe is to mark an absolute and unconditional boundary between the included and the excluded. Those marked off with the stripe are outlandish, visibly set apart. The stripe images and effects a permanent and absolute altering of their condition. But the horror and dread of the spot is that it invades, supervening upon and coexisting with a previously clear and unspotted countenance. Indeed, one might say, in accord with the Levitical principle of uncleanliness, that, where only the corrupt can be striped, only the pure can be spotted. It is almost better to be wholly given over to sin or crime than to bear the foul taint of partial corruption. The striped one is a renegade: the spotted one is an apostate. This, perhaps, is why knights like Clitophon in Sidney’s Arcadia live under the motto of the ermine: “Rather dead than spotted.”

—Steven Connor, “Maculate Conceptions,” Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, vol. 1, no. 1 (2003).

“In those days there was no corn or melons or pepper or sugar-cane, nor were there any little huts such as ye have all seen; and the Jungle People knew nothing of Man, but lived in the Jungle together, making one people. But presently they began to dispute over their food, though there was grazing enough for all. They were lazy. Each wished to eat where he lay, as sometimes we can do now when the spring rains are good. Tha, the First of the Elephants, was busy making new jungles and leading the rivers in their beds. He could not walk in all places; therefore, he made the First of the Tigers the master and the judge of the Jungle, to whom the Jungle People should bring their disputes. In those days the First of the Tigers ate fruit and grass with the others. He was as large as I am, and he was very beautiful, in color all over like the blossom of the yellow creeper. There was never stripe nor bar upon his hide in those good days when this the Jungle was new. All the Jungle People came before him without fear, and his word was the Law of all the Jungle. We were then, remember ye, one people.

Yet upon a night there was a dispute between two bucks—a grazing-quarrel such as ye now settle with the horns and the fore-feet—and it is said that as the two spoke together before the First of the Tigers lying among the flowers, a buck pushed him with his horns, and the First of the Tigers forgot that he was the master and judge of the Jungle, and, leaping upon that buck, broke his neck.

Till that night never one of us had died, and the First of the Tigers, seeing what he had done, and being made foolish by the scent of the blood, ran away into the marshes of the North, and we of the Jungle, left without a judge, fell to fighting among ourselves; and Tha heard the noise of it and came back. Then some of us said this and some of us said that, but he saw the dead buck among the flowers, and asked who had killed, and we of the Jungle would not tell because the smell of the blood made us foolish. We ran to and fro in circles, capering and crying out and shaking our heads. Then Tha gave an order to the trees that hang low, and to the trailing creepers of the Jungle, that they should mark the killer of the buck so that he should know him again, and he said, ‘Who will now be master of the Jungle People?’ Then up leaped the Gray Ape who lives in the branches, and said, ‘I will now be master of the Jungle.’ At this Tha laughed, and said, ‘So be it,’ and went away very angry.

Children, ye know the Gray Ape. He was then as he is now. At the first he made a wise face for himself, but in a little while he began to scratch and to leap up and down, and when Tha came back he found the Gray Ape hanging, head down, from a bough, mocking those who stood below; and they mocked him again. And so there was no Law in the jungle—only foolish talk and senseless words.

Then Tha called us all together and said, ‘The first of your masters has brought Death into the jungle, and the second Shame. Now it is time there was a Law, and a Law that ye must not break. Now ye shall know Fear, and when ye have found him ye shall know that he is your master, and the rest shall follow.’ Then we of the jungle said, ‘What is Fear?’ And Tha said, ‘Seek till ye find.’ So we went up and down the Jungle seeking for Fear, and presently the buffaloes—

‘Ugh!’ said Mysa, the leader of the buffaloes, from their sand-bank.

Yes, Mysa, it was the buffaloes. They came back with the news that in a cave in the Jungle sat Fear, and that he had no hair, and went upon his hind legs. Then we of the Jungle followed the herd till we came to that cave, and Fear stood at the mouth of it, and he was, as the buffaloes had said, hairless, and he walked upon his hinder legs. When he saw us he cried out, and his voice filled us with the fear that we have now of that voice when we hear it, and we ran away, tramping upon and tearing each other because we were afraid. That night, so it was told to me, we of the Jungle did not lie down together as used to be our custom, but each tribe drew off by itself—the pig with the pig, the deer with the deer; horn to horn, hoof to hoof,—like keeping to like, and so lay shaking in the Jungle.

Only the First of the Tigers was not with us, for he was still hidden in the marshes of the North, and when word was brought to him of the Thing we had seen in the cave, he said: ‘I will go to this Thing and break his neck.’ So he ran all the night till he came to the cave; but the trees and the creepers on his path, remembering the order that Tha had given, let down their branches and marked him as he ran, drawing their fingers across his back, his flank, his forehead, and his jowl. Wherever they touched him there was a mark and a stripe upon his yellow hide. And those stripes do his children wear to this day! When he came to the cave, Fear, the Hairless One, put out his hand and called him ‘The Striped One that comes by night,’ and the First of the Tigers was afraid of the Hairless One, and ran back to the swamps howling.”

—Rudyard Kipling, “How Fear Came,” The Second Jungle Book (London: Macmillan and Company, 1895).

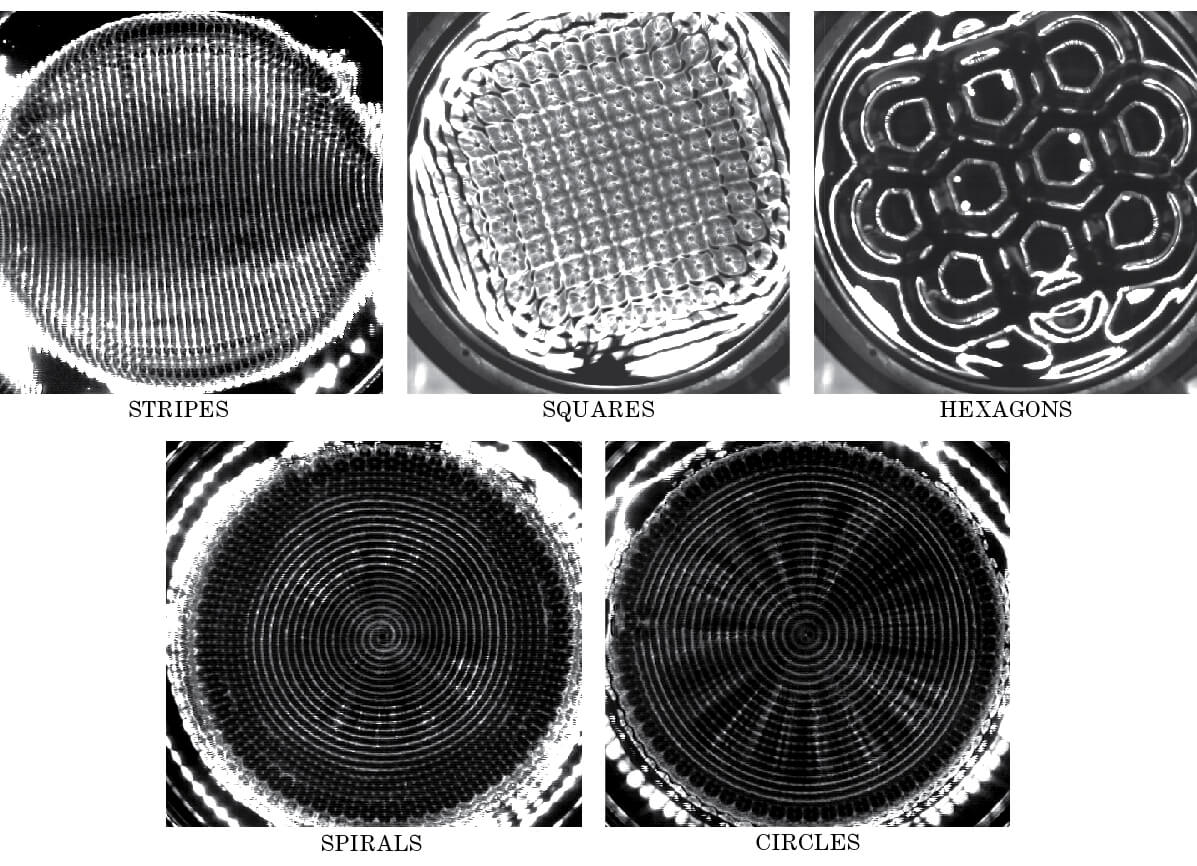

Applying a vertical sinusoidal oscillation to a dish of fluid effectively modulates the acceleration of gravity seen by the fluid. If this modulation exceeds a critical value, the normally flat state of the free surface becomes unstable to the formation of surface waves. These waves have a frequency which is half that of the driving oscillations (the first sub-harmonic). This effect was first reported by Michael Faraday in 1831. In ordinary Newtonian fluids (those that do not exhibit shear thickening or shear thinning) the wave patterns include ones with 1-fold symmetry (stripes), 2-fold symmetry (squares), 3-fold symmetry (hexagons) as well as higher orders of symmetry. When you quickly pass through onset using a circular dish, spirals and concentric circle patterns can also be produced. These patterns are metastable for about 10 minutes. The center then begins to drift to one side and eventually the stable striped pattern results.

—The Experimental Nonlinear Physics Group, “Faraday Waves,” Department of Physics, University of Toronto, n.d. Available at www.physics.utoronto.ca/nonlinear/faraday.html.

What is the sash like. The sash is not like anything mustard it is not like a same thing that has stripes, it is not even more hurt than that, it has a little top.

—Gertrude Stein, “A Substance in a Cushion,” Tender Buttons: Objects, Food, Rooms (New York: Claire Marie, 1914).

Ordinary lines, whether straight or curved, appear as lines and not as areas. They have shape, but they lack the difference between an inside and an outside and are in that respect another special case of our general one.

Geometrically, each straight line that we draw is a rectangle; psychologically, it is not. Shape, on the other hand, is a very important characteristic of lines …

Our question is: Given a certain line pattern, what figures shall we see? What are the general principles that govern this relation? …

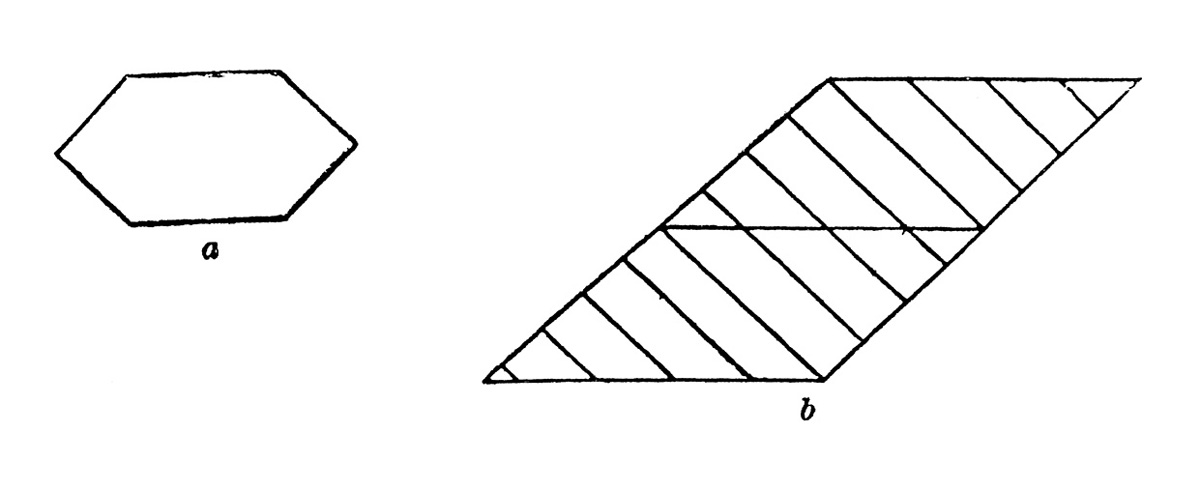

[Figures a and b give] one example, the most difficult one of the series [of Gottschaldt’s experiments]. … Now if the empiricist theory were right, practice in seeing the a figure should make the b figure look like a plus something else. In order to test this assumption three subjects were shown the a figure three times only and eight subjects 520 times. Of the three subjects in the first group two saw the b figures as new figures on all three occasions, and of the eight subjects of the second group five gave the same result. …

The conclusion is that experience does not explain why we see a line pattern in the shape in which we see it, but that direct forces of organization, such as we have analyzed, must be the real cause.

—Kurt Koffka, Principles of Gestalt Psychology (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1935).

On a Monday I was arrested (uh huh)

On a Tuesday they locked me in the jail (oh boy)

On a Wednesday my trial was attested

On a Thursday they said guilty and the judge’s gavel fell

I got stripes—stripes around my shoulders

I got chains—chains around my feet

I got stripes—stripes around my shoulders

And them chains—them chains they’re about to drag me down

On a Monday my momma come to see me

On a Tuesday they caught me with a file

On a Wednesday I’m down in solitary

On a Thursday I start on bread and water for a while

[Repeat chorus]

—Johnny Cash, “I Got Stripes,” At Folsom Prison (live album recorded at Folsom State Prison, California), 1968.

The introduction six or seven years ago of a few simple dot and stripe motifs in expensive hand printed ranges was the first sign that wallpapers could in fact contribute to a modern interior and help banish the austerity of wartime life as Dior’s “New Look” has already attempted to do in other fields.

—John E. Blake, “Designing Wallpapers,” Design, December 1955.

Our wounded need all their patience to put up with the curiosity of non-combatants. A lady, after asking a Tommy on leave what the stripes on his arm were for, being told that they were one for each time he was wounded, is reported to have observed, “Dear me! How extraordinary that you should be wounded three times in the same place!” Even real affection is not always happily expressed.

—Punch, Mr. Punch’s History of the Great War (London: Cassel and Company, 1919).

The Miwok baby is put into a frame or “carrier,” a sort of flat, hooded basket woven of slender sticks. In this it spends the greater part of the first twelve months of its life, and is easily carried about by the mother. The baby carrier has the further advantage of seeming to keep the infant still and contented. It is a notorious fact that Indian babies cry much less than white ones, and the native mothers declare that if they remove the children from their carriers the kicking about of legs and arms soon induces restlessness, discontent, and bawling. The woven hood of each of these tiny cradles is ornamented with a little pattern which differs according to sex. Zigzags or diagonal stripes show that the inmate is a boy, whereas a girl is indicated by a pattern of diamonds.

—A. L. Kroeber, “Indians of Yosemite,” in Handbook of Yosemite National Park, ed. Ansel F. Hall (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1921).

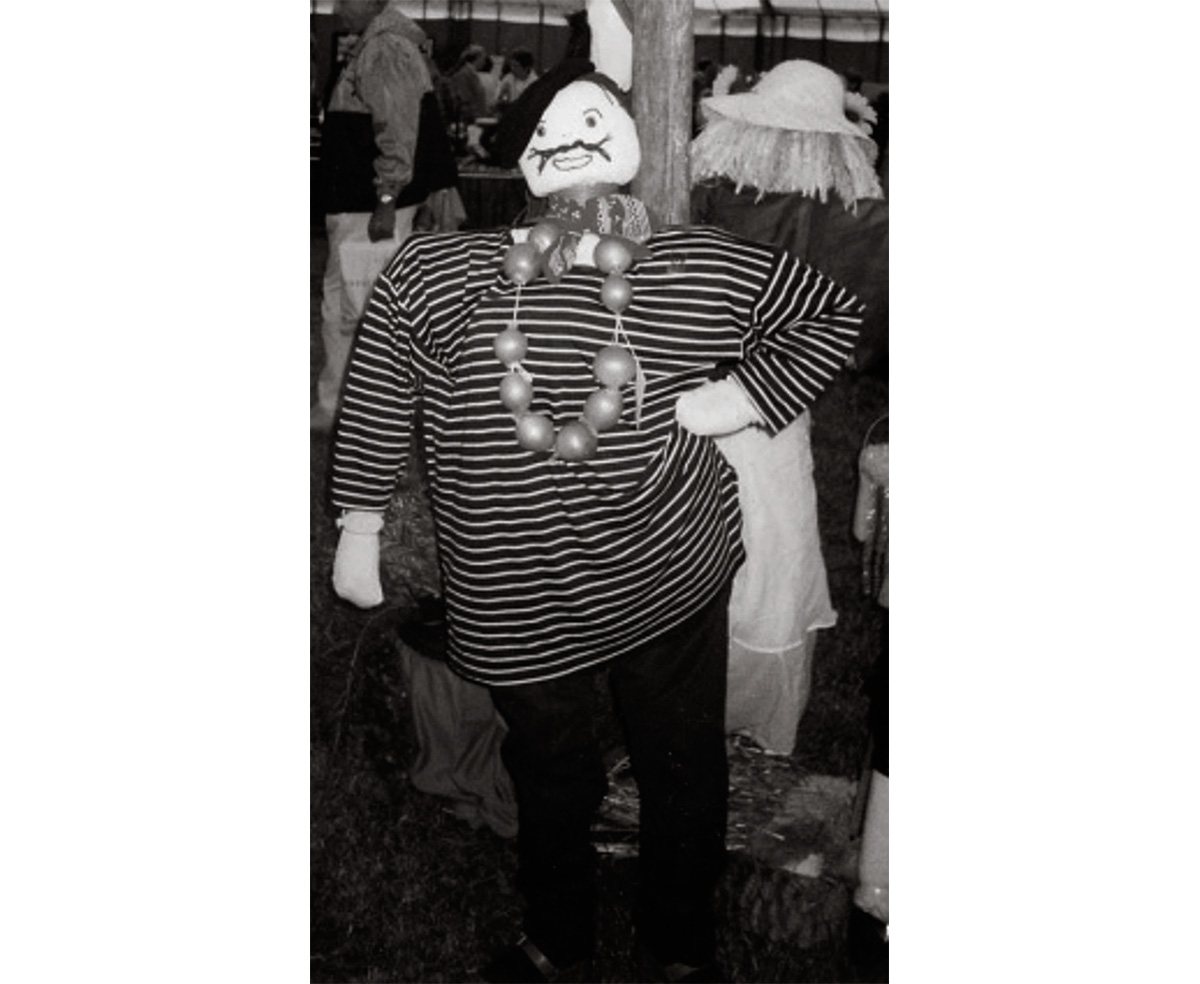

O-o-o—POP! That was the way the eyes had it one evening last week at the preview of an exhibition of Op art held by Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art. Origin of that uncertain feeling was not only the 123 pieces of calculated retina-wrenching on the museum walls. Many of the previewers seemed as bent as the artists on manipulating the wandering eye.

Gisela Oster, for instance, whose husband Gerald had two black-and-white eye foolers in the show, gave him some dazzling competition with a turquoise-and-white-striped evening coat over a turquoise-and-white-striped long dress, but Sculptor Marilynn Karp “out-striped” her by running her black-and-white stripes from dress to stockings to shoes. Painter Jane Wilson was completely optical in a sleek, hooded sheath of white organdy, delightfully dizzy in disks of black and grey. Magazine Editor Pat Coffin wrapped herself in a giant silk stole of peristaltic black dots on a white field that was designed by Painter Bridget Riley, whose Op offerings in the show were titled Current and Hesitate. Teacher-Painter Ruth Ann Fredenthal sported a polychrome print that showed Designer Emilio Pucci to be quite an Operator after all.

Op-outfitted ladies showed a tendency to linger near the pictures that best harmonized with their clothes. Collector Barbara Jakobson flitted among the black-and-white opticals, seeming to appear and disappear in a skintight jump suit with ostrich-feather cuffs under a “cage” of black chiffon, latticed with black velvet. Another black-and-white effect, frequently mistaken for a painting when it was standing still, was the calfskin coat by Furrier Jacques Kaplan, stenciled by Op Painter Richard Anuszkiewicz in a dotty pattern that focused disturbingly on Mrs. Lee Lombard’s pretty kidneys.

—Anonymous, “Fashion: Will the Real Picture Please Sit Down,” Time, 5 March 1965.

Although the “American Stripes” were destined to attain the dignity of the national flag, they did not achieve this distinction at once. (Instead, competition came from two widely different conceptions.) One was the “Pine Tree Flag,” of simple dignity and beauty …, with its solemn device “AN APPEAL TO HEAVEN.” The pine tree, however, had been too long associated with New England to be acceptable as a symbol common to all the colonies. The second contender was the rattlesnake, a purely Revolutionary symbol first featured in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1754, when it served to urge union of the colonies. Truncated serpent, each writhing segment bearing the initials of one of the colonies, it was accompanied by the motto “UNITE OR DIE.” The emblem continued to appear thus, from time to time, until union had been achieved, but meanwhile on flags the dismembered reptile had welded itself into one sleek combative unit, menacingly coiled for attack as it hissed the defiant motto “DON’T TREAD ON ME.” … While the truly mordant snake symbol admirably suited the early colonial mood of angry indignation, upon cooler consideration the “Rattlesnake Flag” would prove repugnant to many. The field would be left largely to the stripes.

—Boleslaw and Marie-Louise D’Otrange Mastai, The Stars and The Stripes: The American Flag as Art and as History from the Birth of the Republic to the Present (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973).

I have already attempted to show in this collection machines that combine the useful with the agreeable; I bring to it now a new invention by means of which the motion of the horse, so beneficial to health, is perfectly imitated. This machine offers a delightful pleasure as well as the healthy tremors of riding, while avoiding the danger that always accompanies those who mount horses: placed in a garden, it is a pretty eye-catcher.

The roof of the building that houses the machine is fashioned in the Chinese taste; at each corner there are some little bells that tinkle in the wind. A robust board from which the saddle is suspended runs through the building and across the ceiling. The user lets the saddle drop by its own weight then makes it rise up again with the aid of a rope hanging from the ceiling and elastic levers; as a result, he finds himself carried up and down rather as if he were riding a horse.

When a woman wishes to take this exercise, one may fit a side-saddle in the manner described in a drawing to be found on the base of the board. Ladies may operate the machine by a second rope suspended for them from the ceiling.

—[n.a.], “The Fitness Horse,” Ideenmagazin für Liebhaber von Gärten, Englischen Anlagen und für Bestizer von Landgütern um Gärten und ländliche Gegenden, sowohl mit geringem als auch grossem Geldaufwand, nach den originellsten Englischen, Gothischen, Sinesischen Geschmacksmanieren zu verschönern und zu veredeln (Ideas Magazine for Lovers of Gardens, English Garden Facilities, and for Owners of Country Estates, about Gardens and Rural Areas, and for Those with Little As Well As Large Amounts of Money at Their Disposal, to Beautify and Refine According to the Most Original English, Gothic, and Chinese Tastes), 1797. Trans. Cathy Haynes.

“Stop, let me tell you something else before you go on,” said Holy Thursday anxiously. “Take care of your life; enter into conversation with no one, don’t ride too fast, don’t let go of the water, believe no promises, and fly from lips that speak sweet words! Go as you came, the way is long, the world is wicked, and you have something very valuable in your hand, so listen to me. I give you this handkerchief, it is made neither of gold, silver, silk, nor pearls, but striped linen; take good care of it, it is enchanted. Whoever carries it no thunderbolt can strike, no lance stab, no sword slay, and no bullet pierce.”

—“The Fairy Aurora,” Roumanian Fairy Tales, collected Mite Kremnitz, adapted and arranged J. M. Percival (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1885).

In normal times, butter muslin or surgical gauze, bought at little cost and home-dyed, can be used for veils, waist bands, etc. (Surgical gauze is obtained from chemists in packets of one yard square. It can be stiffened a little by ironing when damp.) The bands can also be improvised by long scarves or odd lengths of scrap material.

Striped material, e.g., peasant weave, which is used for curtains and bed-spreads, is very adaptable, and generally, no cutting is necessary. Deck-chair material can also be used, but is almost too stiff. Striped and square-patterned dusters make good head-dresses. Large, striped bath towels can sometimes be adapted.

The abbeyeh of the Palestinian peasant man may be made from a smallish brown or grey blanket. The stripes can be chalked on or stripes of light material or paper tacked or pinned on.

—Anonymous, Let’s Dress Up! Using & Improvising Overseas Costumes (London: Edinburgh House Press, 1949).

A nineteen ten illustration by fashion designer Paul Poiret showing one of his dresses on a slender woman and on a less slender one.

Take a whiff on me,

Take a whiff on me,

Everybody take a whiff on me.

Well-a-hey-hey,

Baby, take a whiff on me.

—The White Stripes, “Take a Whiff on Me,” Under Blackpool Lights, 2004.

Aposematic [“warning signal”] color patterns are found everywhere throughout the insects, from black and yellow-striped stinging wasps to black and red, bitter-tasting ladybird beetles, or brightly-colored, poisonous tropical butterflies. Although warning coloration has involved fascination, empirical and theoretical studies for some time, the puzzle of aposematism still motivates much debate today. First, although there is little doubt that bright coloration is in many cases an anti-predatory strategy, how aposematism evolves is far from clear. This is because brightly-colored mutants in a population of cryptic (camouflaged) prey are more exposed to predators. How can a warning coloration evolve in a prey if the very first mutants exhibiting such coloration in the population are selected against? Second, the reasons why warning colors should be bright and conspicuous are not always clear, and may be multiple. Are aposematic colors “road signs” that predators learn better to differentiate from edible prey, or are bright colors more easily memorized and associated to bad taste by predators? ... Finally, why are warning patterns highly diverse in the insect world, whereas all toxic prey would gain by bearing the same color thus reducing the probability of being sampled by a naïve predator?

—Mathieu Joron, “Aposematic coloration” in Encyclopedia of Insects, ed. Vincent H. Resh and Ring T. Cardé (New York: Academic Press, 2002).

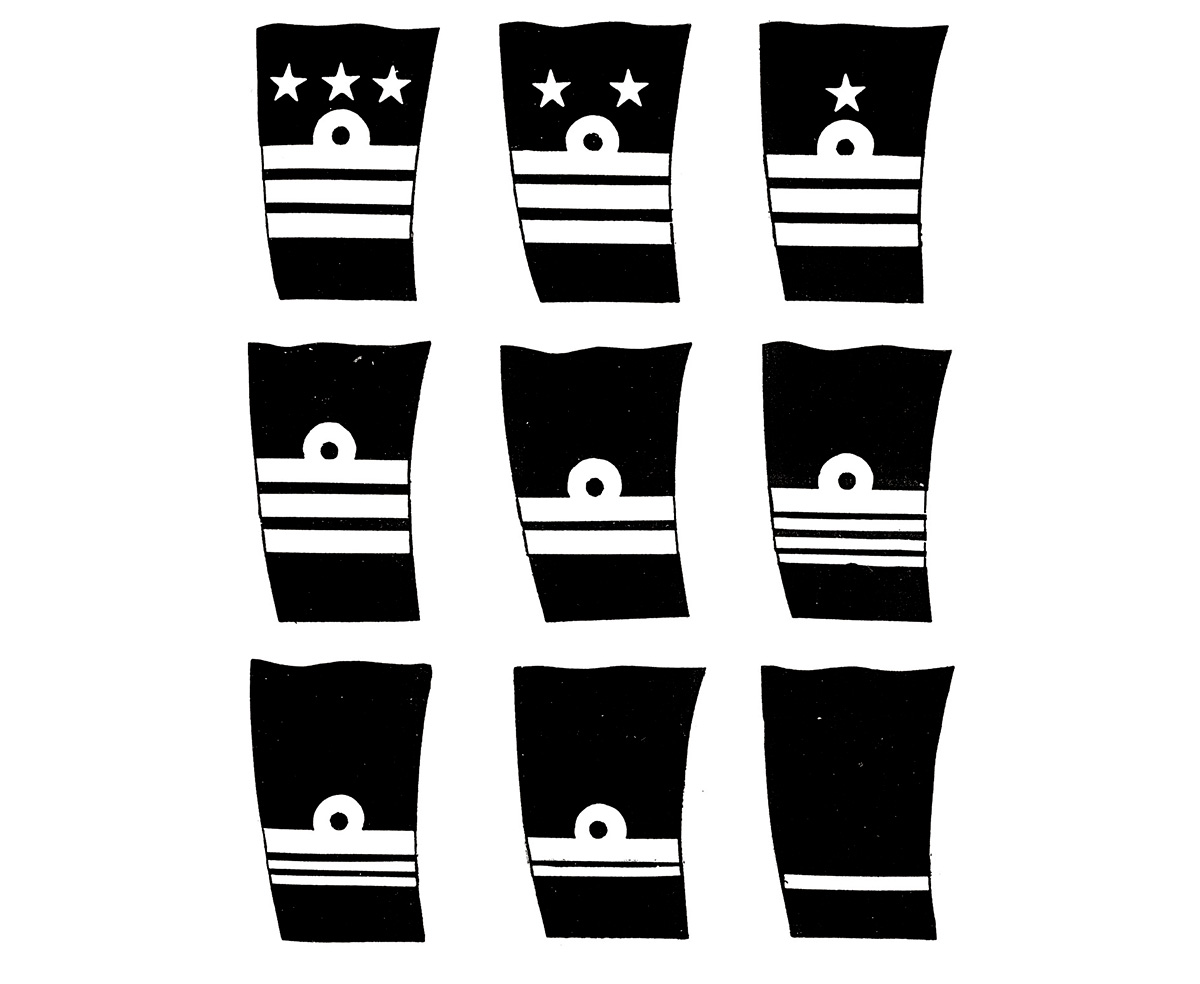

A.E.A.F. stripes were marked chordwise on each wing and also around the fuselage in alternate white and black stripes as shown. This marking was applicable to all operational aircraft of the Allied Expeditionary Air Forces, June 1944. This Spitfire is a photographic reconnaissance aircraft, which accounts for its “B” type roundel on the fuselage and an overall cerulean blue finish.

—Bruce Robertson, Aircraft Camouflage and Markings 1907–1954 (Letchworth, UK: Harleyford, 1956).

Indeed, from as early as before the year 1000, images in the Western world had acquired the habit of reserving a pejorative status for striped clothing. The first figures who are graced with them—at first, in illuminations, then in mural paintings, and later in other media—are biblical figures: Cain, Delilah, Saul, Salomé, Judas. Like red hair, striped clothes constitute the usual attribute of the traitor in the Scriptures. Of course, just as they are not always redheads, Cain and Judas, for example, are not always in stripes; but they are so clothed more frequently than all other biblical figures, and those stripes, when present, are enough to reveal their treacherous characters.

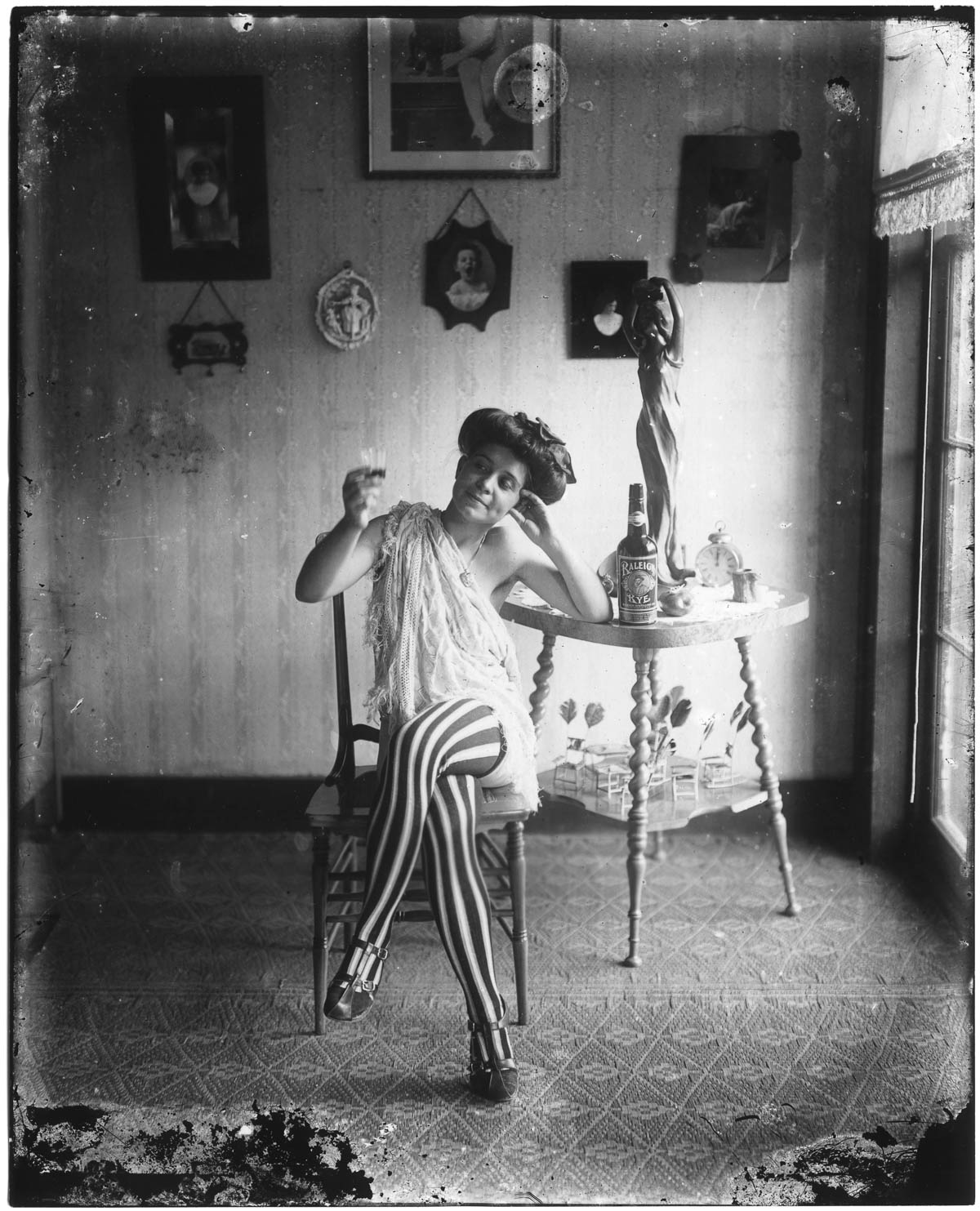

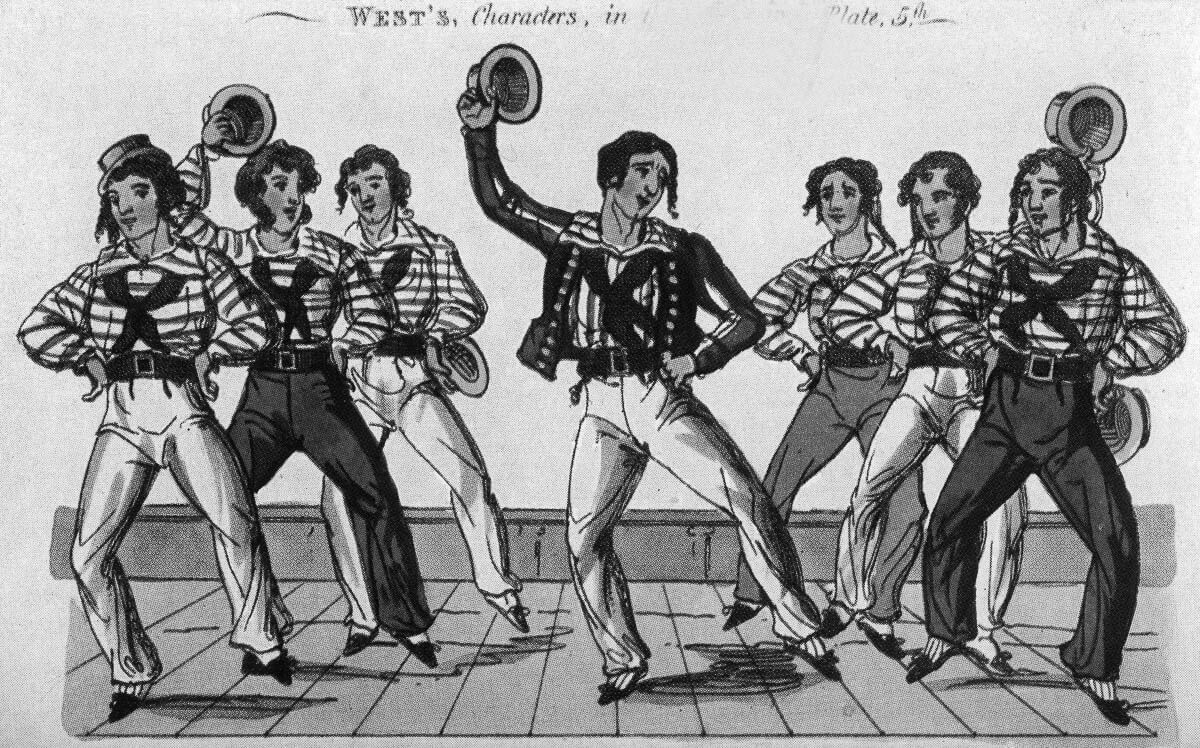

Beginning from the mid-thirteenth century, the list of “bad” characters dressed in such a way grows considerable, notably in the secular miniature. … In the image as in the street, all those outside the social order are often marked in this way by a striped attribute or piece of clothing, whether because of a condemnation (forgers, counterfeiters, traitors, criminals) or because of an infirmity (lepers, hypocrites, the simpleminded, the insane), whether because they are employed in an inferior occupation (valets, servants) or an ignominious trade (jugglers, prostitutes, hangmen, to which the image often adds three contemptible tradesmen: the blacksmiths, who are the sorcerers, the butchers, who are the bloodthirsty ones, and the millers, who are the stockpilers and the tight-fisted ones) or because they are no longer Christian (Muslims, Jews, heretics). All these individuals transgress the social order, like the stripe transgresses the chromatic order and the order of dress.

—Michel Pastoureau, The Devil’s Cloth: A History Of Stripes and Striped Fabrics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991).

No more conspicuous animal can be well conceived, according to common idea, than a zebra; but on a bright starlight night the breathing of one may be heard close by you, and yet you will be positively unable to see the animal; if the black stripes were more numerous he would be seen as a black mass; if the white, as a white one; but their proportion is such as exactly to match the pale tint which the arid ground possesses when seen by moonlight.

—Francis Galton, quoted in J. Huddlestone, “Camouflage in Nature: General Resemblance,” in C. H. R. Chesney, The Art of Camouflage (London: Robert Hale, 1941).

I’ve been asked countless times—in person, through phone calls, and in letters—how stripes are made on grass. … A wide range of myths exist on how patterns are created, ranging from being painted in varying shades of green to alternating types of grasses, mowing at different height, and being fertilized differently. It’s not as mysterious as you might think. A pattern is created when the grass blades are bent in the direction the mower is travelling by a roller mounted behind the cutting blades. The roller provides downward pressure to bend the grass blades so that reflecting light forms alternate dark and light stripes. When you’re mowing and you get to the end of the line you’re making and you turn around, the light stripe you just made will now appear dark. Stripes or shapes that look light when viewed from one direction will look dark from the other direction, and vice versa. Remembering this will keep you from getting confused when developing your designs.

—David R. Mellor, Picture Perfect: Mowing Techniques for Lawns, Landscapes, and Sports (Chelsea, MI: Ann Arbor Press, 2001).

Supposing that an ape-like ancestor developed into man, on the principles of natural selection; then his development has taken place in a manner directly contrary to the acknowledged law of natural selection. He has developed backwards; his frame is in every way weaker; he is wanting in agility; he has lost the prehensile feet; he has lost teeth fitted for fighting or crushing or tearing; he has but little sense of smell; he has lost the hairy covering, and is obliged to help himself by clothes. If this loss was ornamental it is quite unlike any other development in this respect, since no other creature has the same; for ornamental purposes the fur becomes colored, spotted, and striped, but not lost.

—B. H. Baden-Powell, Creation and Its Records: A Brief Statement of Christian Belief with Reference to Modern Facts and Ancient Scripture (London: n.p., 1855).

Animals seem to see sharp contrast on the floor as a false visual cliff; they act as if they think the darks spots are deeper than the lighter spots. That’s why cattle guards work on roads. A cattle guard is a pit dug across a road, covered with metal bars. A car can drive over it and a cow could walk over it, but it won’t because it sees the two-foot drop-off between the bars. …

Cattle guards are expensive to build, so a lot of times the Department of Transportation just uses a standard line-painting machine (that’s the machine they use to paint the center line on highways) to paint batches of bright white lines across the highway going in the same direction as a cross walk. It’s a poor man’s cattle guard.

When the cattle aren’t highly motivated to cross the road, a grouping of twenty white lines painted six inches apart will make them stay put, because the contrast scares them. If the cattle are highly motivated, it’s a different story. If you’ve got mama on one side and baby on the other, painted lines won’t work. Or if cattle are starving they’ll cross the lines to get to better grazing on the other side of the road. But under normal circumstances, painted lines work just fine.

—Temple Grandin and Catherine Johnson, Animals in Translation: Using the Mysteries of Autism to Decode Animal Behaviour (London: Bloomsbury, 2005).

The conservative view is that pinstripes are sober, reliable stripes, which have their origins in the striped pants that City bankers used to wear with a morning coat. Individual banks would identify themselves by the different stripes of the pants. Eventually, the stripes were applied to the entire suit and the ubiquitous City uniform was born. …

Other sources refute this idea. The opposing theory is that the true origin of the pinstripe is the boating suit of the 1890s. The early 20th century saw an explosion of pattern and self-expression in men’s clothing, and the pinstripe was probably the rather showy alternative to other, more somber options.

—Mark Hampshire and Keith Stephenson, Stripes: Communicating with Pattern (Mies, Switzerland: RotoVision SA, 2006).

[A] banker can wear a striped tie with ease, but a man who comes into the office with a spotted tie still risks being thought of as a fop, an oaf or an exhibitionist.

—Steven Connor, “Maculate Conceptions,” Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, vol. 1, no. 1 (2003).

Factual error: Major Strasser’s uniform trousers have a double stripe running down the side. Double stripes were reserved for General Officers therefore Strasser would not be entitled to wear them.

It is necessary to admit that it is not only abstract images but also critical artistic practices that all too easily become mere décor, and the line between accepting given conditions critically and surrendering to them is exceedingly thin and itself subject to historical change. An interpretation based entirely in the logic of ornament and crime would not even be precipitous in the case of Daniel Buren, where it seems to be so evident that a situational sign, which in the 1960s functioned merely as an indicator for intervention, has transformed over the decades more and more into an element of form and design. Buren’s stripes do bear their own historicity and indicate in their obvious designed-ness something beyond them, utilizing their decorative nature for the production of self-reflective situations.

—Helmut Draxler, “Letting Loos(e): Institutional Critique and Design,” in Art After Conceptual Art, ed. Alexander Alberro and Sabeth Buchmann (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006).

1. At a noon or afternoon wedding.

2. On Sunday for church (in the city).

3. At any formal daytime function.

4. In England to business.

5. As usher at a wedding.

6. As pall-bearer.

—Emily Post, Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1922).

The [first Rainbow Flag] design may have been influenced by flags with multicolored stripes used by various left-wing causes and organizations in the San Francisco area in the 1960s. The Rainbow Flag originally had eight stripes (from top to bottom): hot pink for sex, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for sun, green for serenity with nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony, and violet for spirit. Handmade versions of this flag were flown in the 1978 Gay Freedom Day Parade. …

After the November 1978 assassination of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and openly gay Supervisor Harvey Milk and the subsequent lenient sentence given to their killer, former Supervisor Dan White, the Rainbow Flag began to be used in San Francisco as a general symbol of the gay community. San Francisco–based Paramount Flag Co. began selling seven-striped (top to bottom: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet) flags from its Polk Street retail store, which was located in a large gay neighborhood. These flags were surplus stock which had originally been made for the International Order of Rainbow for Girls, a Masonic organization for young women. When [Rainbow flag designer Gilbert] Baker approached Paramount to make flags for the 1979 Gay Freedom Day Parade, Paramount informed Baker that fabric for hot pink was not available for mass production, and Baker dropped the hot pink stripe.

—Steve Kramer, “History of the Gay Pride/Rainbow Flag”, in Flags of the World, 24 April 1998. Available at fotw.fivestarflags.com/qq-rb_h.html.

The colored stripes in toothpaste are applied as the toothpaste exits the container as it passes through a bladder of dye.

—Steve Kummer, Fog Creek Software Forum, 12 April 2002.

Such is the mood with which I approach the end of our probe into the error which is prison, and prisoners, and crime, and criminals. The answers to our diarist’s questions stand out sharp and clear against the background of human life. We know why men “come back to prison a second, third or fourth time.” It is because society lacks faith in its own measures for rehabilitation. It is because the prisoner, on his discharge from prison, is conscious of invisible stripes fastened upon him by tradition and prejudice.

—Warden Lewis E. Lawes, Invisible Stripes (New York: Farrar & Rhinehart, 1938).

As Syme strode along the corridor, he saw the Secretary standing at the top of a great flight of stairs. The man had never looked so noble. He was draped in a long robe of starless black, down the center of which fell a band or broad stripe of pure white, like a single shaft of light. The whole looked like some very severe ecclesiastical vestment. There was no need for Syme to search his memory or the Bible in order to remember that the first day of creation marked the mere creation of light out of darkness. The vestment itself would alone have suggested the symbol; and Syme felt also how perfectly this pattern of pure white and black expressed the soul of the pale and austere Secretary, with his inhuman veracity and his cold frenzy, which made him so easily make war on the anarchists, and yet so easily pass for one of them. Syme was scarcely surprised to notice that, amid all the ease and hospitality of their new surroundings, this man’s eyes were still stern. No smell of ale or orchards could make the Secretary cease to ask a reasonable question.

—G. K. Chesterton, The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare (Bristol, UK: J. W. Arrowsmith, 1908).

Looking nearly straight up into the vault region of the mature storm, we can see impressive striations on the updraft tower. The supercell storm is not rotating hard in the mid-levels. This is called a “barber pole” due to the stripes (striations).

—Chris Collura, “US Midwest Storm Chase Log,” 21 May 2006. Available at sky-chaser.com/mwcl2006.htm.

“The barber’s pole,” it is [stated in the Antiquarian Repertory], “has been the subject of many conjectures, some conceiving it to have originated from the word poll or head, with several other conceits far-fetched and as unmeaning; but the true intention of the party colored staff was to show that the master of the shop practised surgery and could breathe a vein as well as mow a beard: such a staff being to this day by every village practitioner put in the hand of the patient undergoing the operation of phlebotomy. The white band, which encompasses the staff, was meant to represent the fillet this elegantly twined about it.”

—William Andrews, At the Sign of the Barber’s Pole (Cottingham, UK: J. R. Tutin, 1904).

A large drum, painted on the inside with black-and-white vertical stripes, rotates slowly about its axis. When a visitor focuses on the stripes, the eyes will involuntarily follow the stripes momentarily and then snap back. This can be observed by either watching another visitor’s eyes or closing one eye and placing one finger gently against the eyelid to feel the movement. The involuntary motion can be stopped by focusing on a finger near the drum, but then the stripes are blurred.

—From a “Catalogue of Exhibits for Sale” issued by Exploratorium.

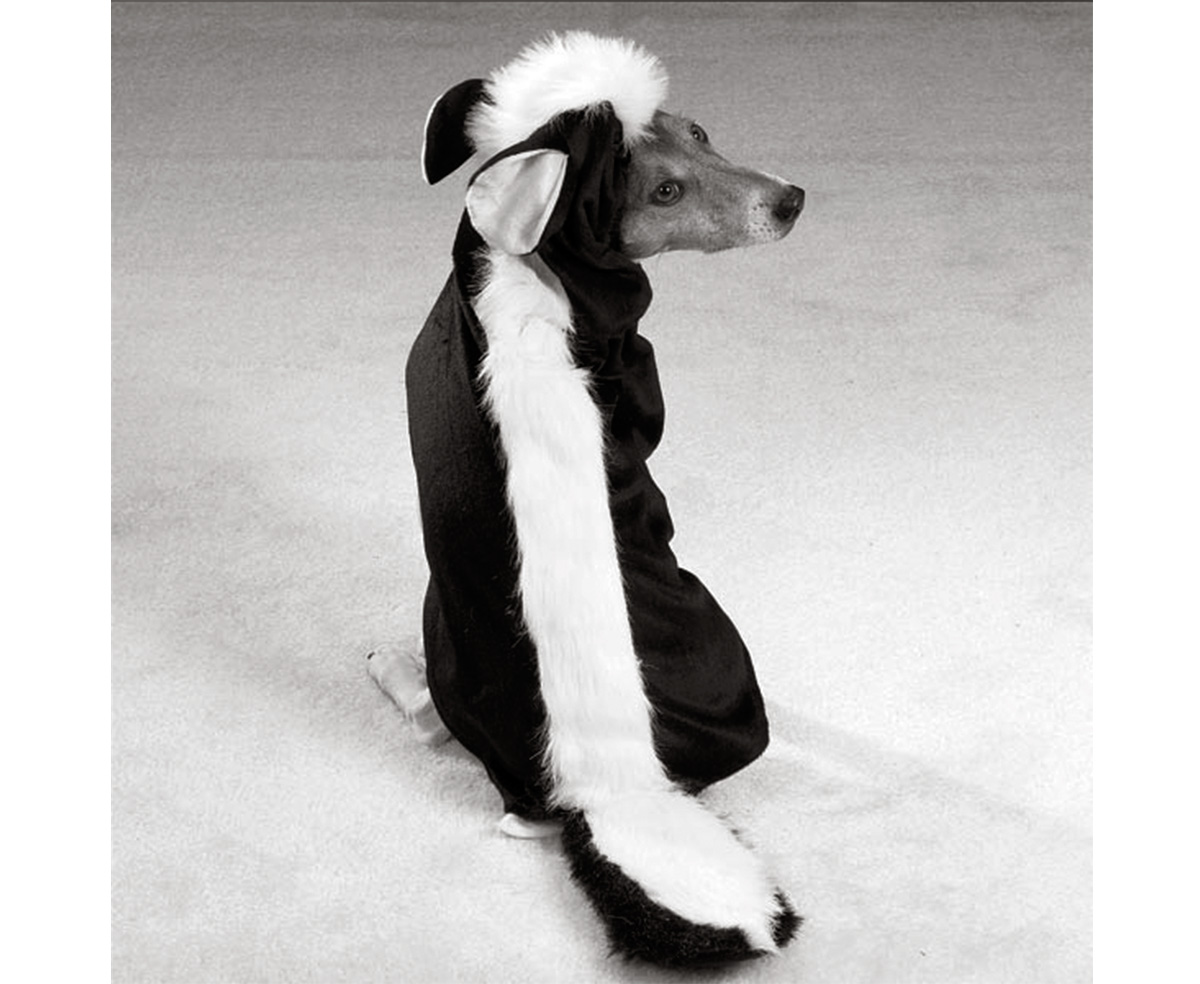

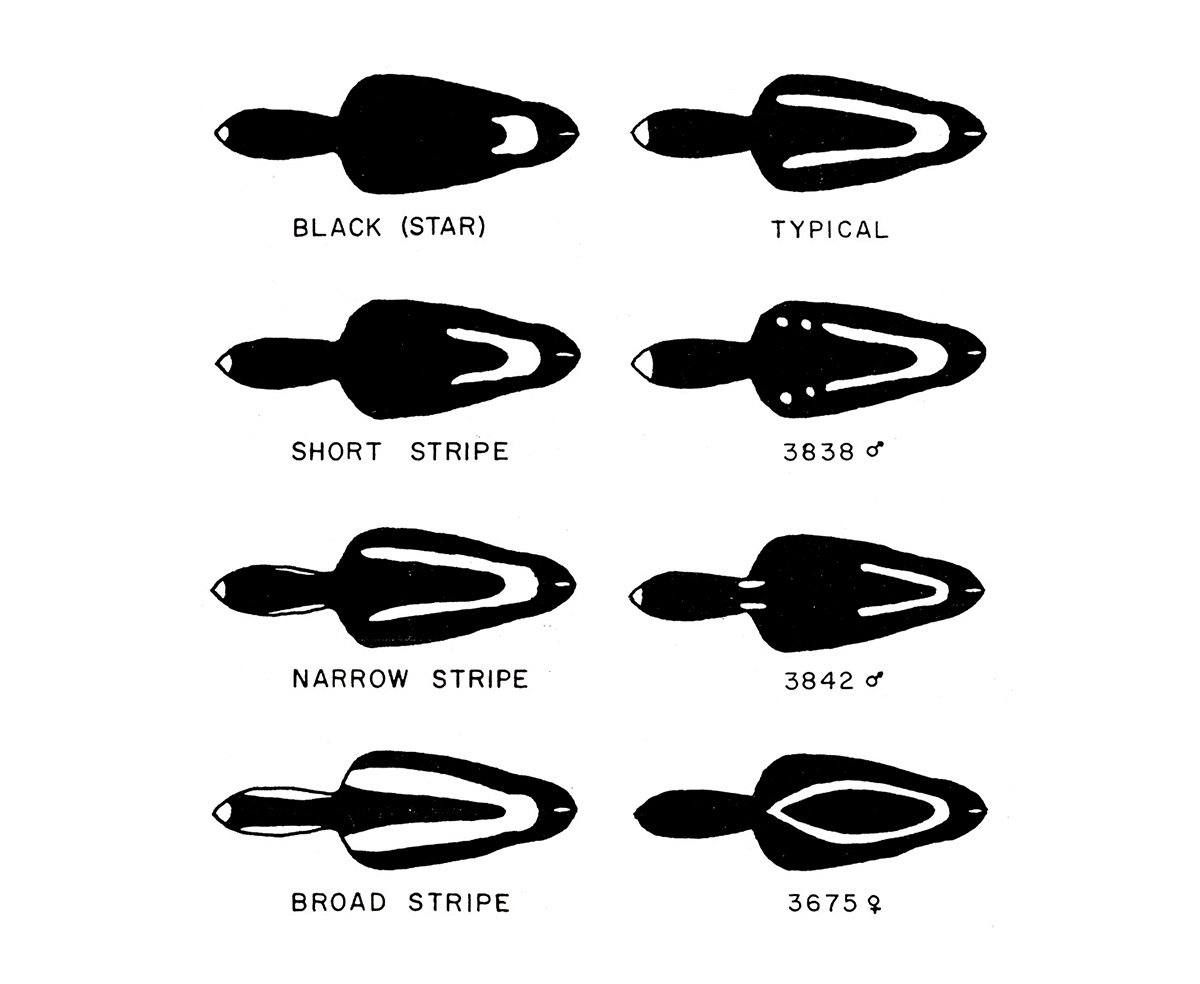

Right: Atypical color patterns of three striped skunks caught in northwestern Illinois.

From B. J. Verts, The Biology of the Striped Skunk (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1967).

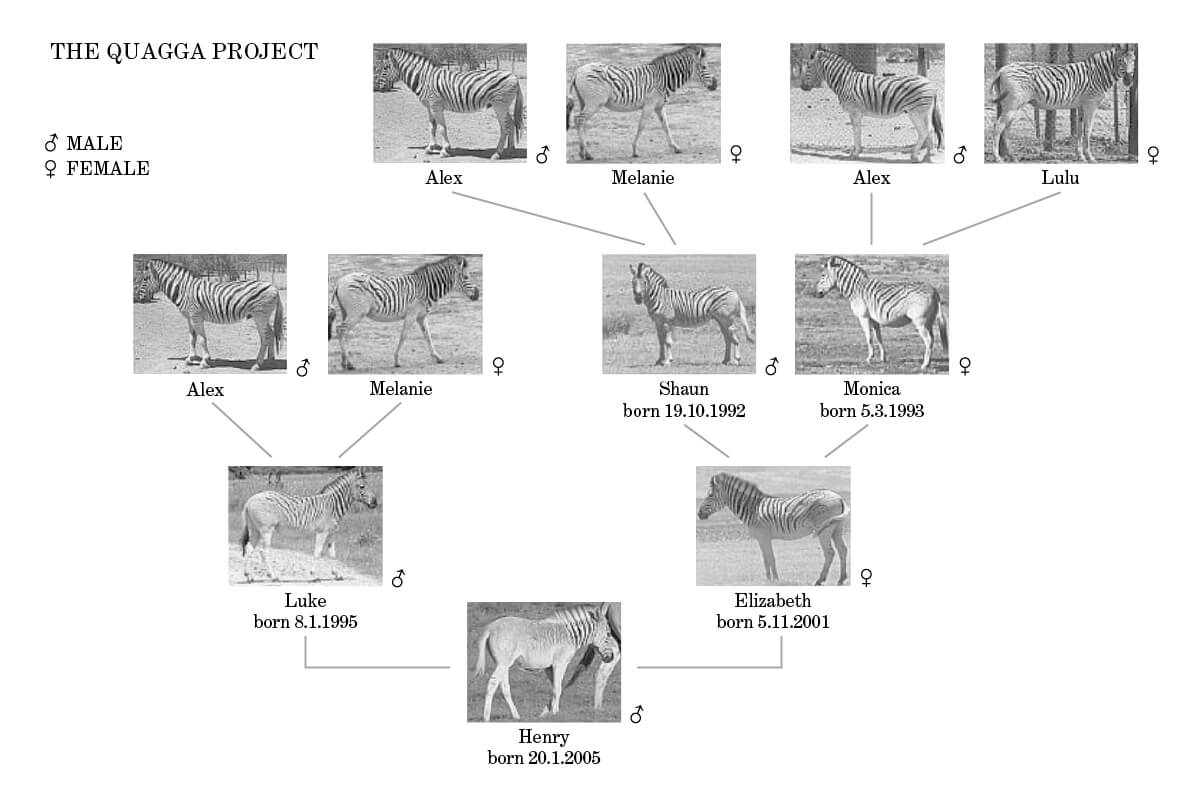

If a species of animal or plant has disappeared from the earth, either through natural causes, or through mankind’s activities, the loss is irreversible. However, the extinct “Quagga” was not a zebra species of its own but one of several subspecies or local forms of the Plains Zebra. This fact makes a big difference—the Quagga’s extinction may not be forever! An exciting breeding project has been on-going since 1987 which aims at reversing the Quagga’s extinction. …

By breeding with selected southern Plains Zebras an attempt is being made to retrieve at least the genes responsible for the Quaggas’ coloration.

The project, if successful, will rectify a tragic mistake made over a hundred years ago through greed and short sightedness. Once again herds of Quaggas will roam the plains of the Karoo.

—Reinhold Rau, “Extinction is Forever” and “Selective Breeding,” The Quagga Project, 2006. Available at quaggaproject.org/the-project/.

Delightful designs composed of multiple lines, stripe patterns became the vogue as kimono patterns during the Edo period (1603–1867), and countless combinations have been created. Today they are used not only for kimono, but every conceivable article of clothing from underwear to outerwear, as well as packaging, interior design, and even modes of public transportation.

—Touzan and Yatara stripes from [n.a.], Stripe Design: Textile Patterns in Japan (Tokyo: Pie Books, 2005).

Implicasphere is an occasional publication. Past editions include “String,” “Mice,” “Folly,” “The Nose” and “Salt & Pepper.”

Implicasphere is edited by Cathy Haynes and Sally O’Reilly.

The first three editions were commissioned by PEER. The latter two were supported by the Moose Foundation for the Arts and the Elephant Trust. This edition is supported by Arts Council England, London, and the Henry Moore Foundation.

Thanks to Cabinet, New York.

Printed in an edition of 13,000 on Cyclus Offset (recycled).

© Implicasphere Ltd, London, 2007. Registered company no. 5757303.