Inventory / Wanted and Unwanted at the Zoo

I’ll trade you a freckled duck for a spiny terrapin

Clem Blakemore

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

Rather like the classifieds buried in the back pages of a newspaper, or the “Lonely Hearts” section of a magazine, official lists advertising surplus and sought-after animals are maintained internationally by associations of zoos and aquaria. The lists have two roles. In one way, they function as a kind of dating service, of particular value to members of endangered species, that pairs off “attractive and available” animals. They also imitate (vaguely tragic) rummage sales, allowing zoos to cast off “excess stock”—undesirables who simply aren’t a hit with the visitors, or happen to belong to a captive population overzealous in its reproductive habits.

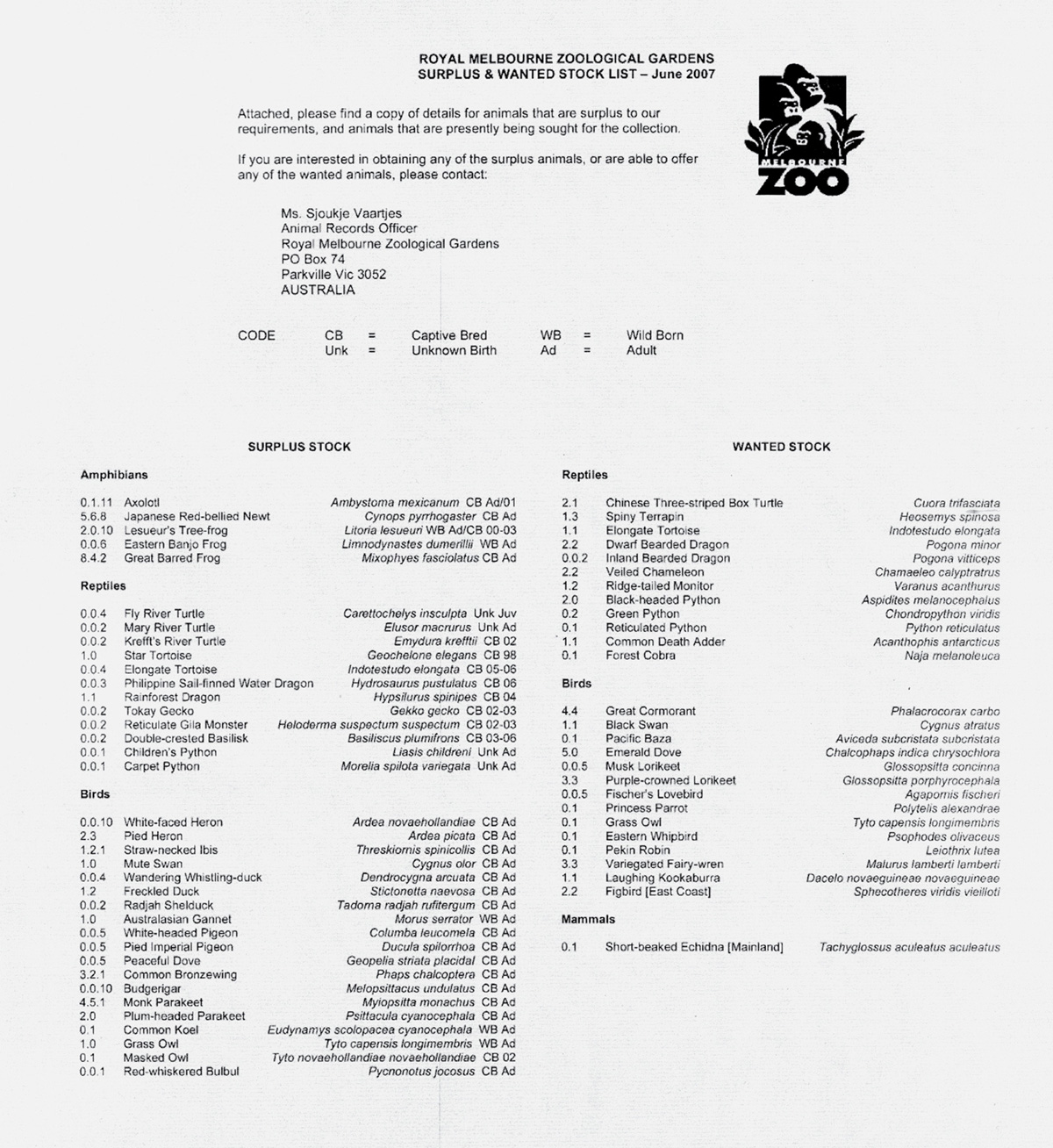

Printed here is the most recent list, as of publication, from the Royal Melbourne Zoological Gardens. Organized into two categories, the names of the species registered in each are accompanied by their “vital statistics”: quantity, gender, age, and origin. The numbers noted on the far left column reflect the male to female ratio; a third digit indicates neutered or sexually unidentified animals whose matchmaking potential has yet to be exploited (usually birds or reptiles, which often require DNA-testing to confirm gender). The codes on the right of the Latin nomenclatures signify three categories used to differentiate between wild, captive, and “unknown” births, as well as between adult and juvenile animals; for some of the species bred in captivity, dates of birth are also recorded.

Source details about each animal group in these lists are drawn from data logged in “studbooks,” intimate records documenting the private lives of every member of a captive species. Historically, studbooks were used to register differences between individuals of the same species in order to improve livestock through selective breeding. The first official record of this kind, set up in England in the late nineteenth century, was the “General Stud Book for Thoroughbred Horses.” The genes of all thoroughbreds living today can still be traced back to three “foundation sires,” stallions imported from the Middle East in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: the Darley Arabian, Godolphin Arabian, and Byerly Turk. Later, in the 1930s, the practice was appropriated by zoos to help prevent the extinction of wild animals in captivity; the first international studbook of this kind, for the European bison, was started in 1932 by Heinz Heck, the then-director of the Hellabrun Zoo in Munich.

Today, the coordinated management of zoo populations is supervised by national, regional, and global associations, with which most major zoos are affiliated. As comprehensive records of animals in captivity, contemporary digitized studbooks enable zoos to monitor and manipulate their collections, satisfying both display preferences and breeding requirements. New studbooks, proposed for those species not yet covered, must be endorsed by the relevant “Taxon Advisory Group” (or TAG), and ought to include the full known history of that species in captivity. The data gathered by “studbook keepers” (zoo employees who take on the responsibility of maintaining and updating the record for each species) should incorporate not only movements between institutions, but also births, deaths, and parental information.

A well-kept studbook should therefore function as an up-to-date source of genealogical data for each animal within the captive population of a species, including those deceased. Starting preferably with the original animals caught in the wild, these records vary in detail and geographic scope, covering national, regional or global collections. Demographic and genetic analyses drawn from a studbook’s data can be harnessed to increase the numbers of endangered species born into captivity. Initially employed as a means of selecting and promoting a limited number of characteristics beneficial for the cultivation of domestic animals, studbook keeping has thus developed into a method of ensuring maximum genetic diversity within captive populations.

Financial and practical burdens result in the majority of transfers taking place within one continent, and even nationally in countries with many zoos. Occasionally institutions are able to send animals to establishments or dealers not affiliated with the regional regulating body, such as permit-holding animal sanctuaries, but must in these circumstances ensure the destination’s husbandry conditions are suitable for the species concerned. Access to the lists of surplus and wanted animals is, in the United States, restricted to those working for accredited establishments; however, Melbourne Zoo, a member of the Australasian Regional Association of Zoological Parks and Aquaria, has been more forthcoming. With any luck the animals on their list, including the pair of wanted Common Death Adders and four unwanted Wandering Whistling-ducks, will reach loving partners, or at the very least appreciative new homes, safely.

Thanks to Sjoukje Vaartjes, Animal Records Officer, Royal Melbourne Zoological Gardens (Australia); Katherine Mcleod, Exhibitions Specialist, Bronx Zoo (US); Harry Schram, Executive Director, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (The Netherlands); Peter Dollinger, Director, World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (Switzerland); Pierre De Wit, EEP-Coordinator for Humboldt Penguins, Zoo Emmen (The Netherlands); Christine Jackson, Zoo Registrar, Drussilas Park (UK); Emma Kenly, Press Officer, Zoological Society of London (UK); Alison Reiser, Communications, Bronx Zoo (US), and to Barbara Pacheco.

Clem Blakemore is an editorial assistant of Cabinet.