Ingestion / More Shoes! More Boots! More Garlic!

Werner Herzog’s gastronomic bet

Jeffrey Kastner

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

The act of eating the inedible—especially when performed as the centerpiece of symbolic penance or ritual humbling—has a pedigree of sorts, if not in actual practice then certainly in language and the cultural imagination. Whether eating one’s hat or one’s shirt, crow or humble pie (in actuality, a complex corruption of umble pie, an indeed rather “humble” medieval dish, made from deer offal baked in crust and typically served to the below-stairs staff), such conduct would seem to turn all normative understandings of cuisine on their head. Instead of providing enjoyment and nourishment, this peculiar brand of masochistic degradation is instead intended to enact modes of penitence, to evoke pathos. It may stop short of actual physical harm, but it nevertheless manages to channel both private mortification and public shame via one of humanity’s most necessary and uniquely personal activities.

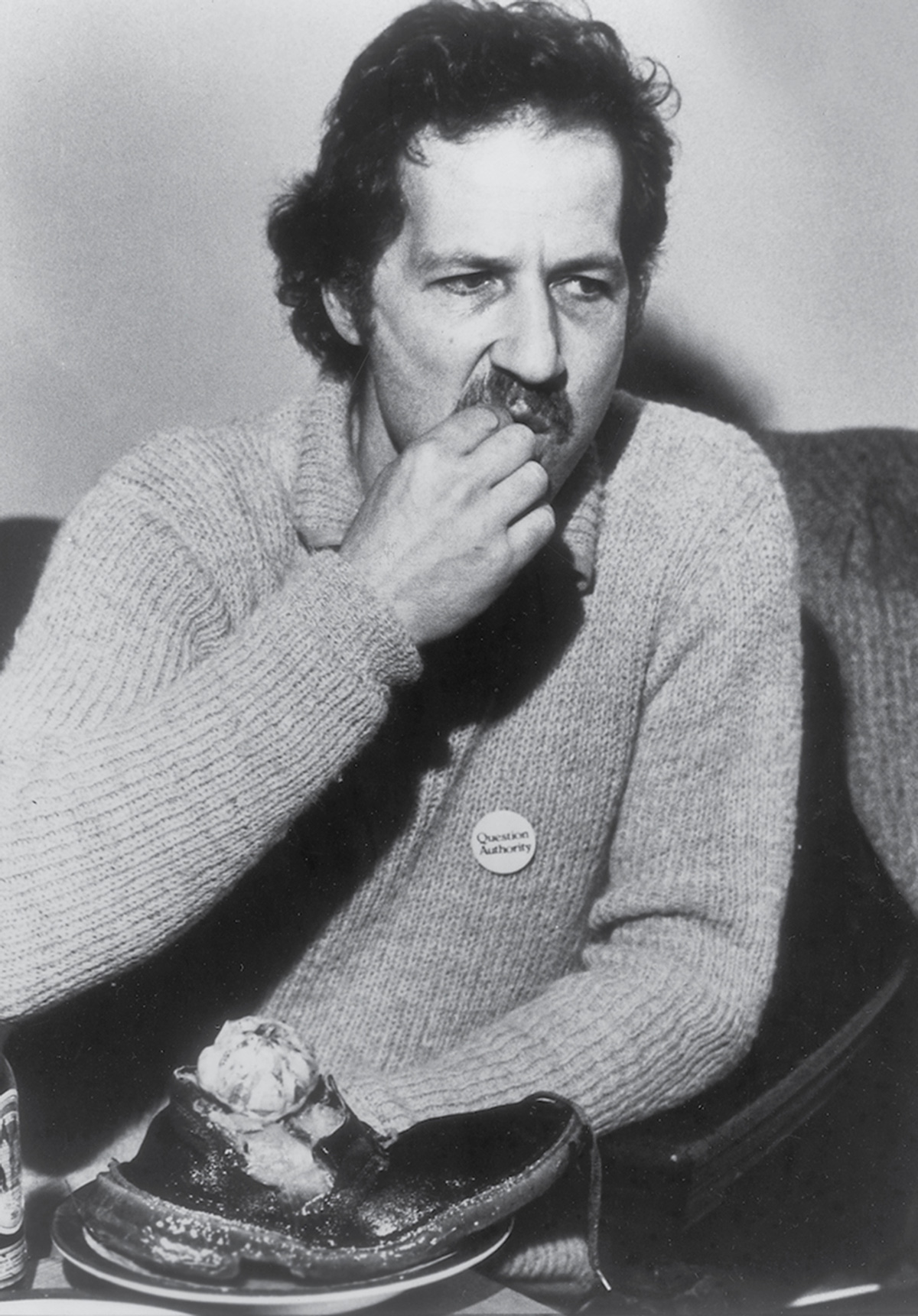

Examples of individuals voluntarily ingesting the theoretically indigestible are for the most part confined to the aforementioned realm of rhetoric, to art (witness the wounding poignancy of Chaplin’s boiled shoe in the Thanksgiving scene from The Gold Rush), or to borderline pathological attempts to garner publicity, as in the case of Michel “Monsieur Mangetout” Lotito, the French entertainer who has famously eaten bicycles, televisions, and an entire Cessna airplane. Yet in Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, a documentary from 1979 by Les Blank, the German director, in characteristic fashion, puts his own idiosyncratic spin on the concept: he cooks and then eats, in front of an appreciative audience, one of his own shoes (real leather, as opposed to Chaplin’s licorice) as a way of satisfying a bet lost to his friend and protégé, Errol Morris.

In the mid-1970s, Morris—later to become the director of such celebrated documentary films as The Thin Blue Line and Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control—had yet to find his true calling. A gifted musician who had trained as a young man to be a concert cellist, he had left the conservatory behind and gone the familiar liberal arts route instead, studying history first at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in graduate school at Princeton and later, after dropping out there, taking up philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. Yet he ended up spending significantly less of his Bay Area time in class than he did at the Pacific Film Archive (PFA), the legendary rep house/hangout on the Berkeley campus. It was through the PFA’s then-director Tom Luddy that Morris met Werner Herzog. During one of numerous hiatuses in his studies, Morris—who by then had begun steeping himself in stories of social outcasts and deviants, without any particular sense of what might become of such research—had returned to Wisconsin and done a number of interviews with the notorious serial killer, grave robber, and cannibal, Ed Gein. Herzog, who by then already had a dozen or so films under his belt, shared Morris’s fascination with outsiders. Recognizing a kindred spirit—if not yet at that point a professional equal—he even schemed with Morris to go in 1975 to Gein’s hometown of Plainfield, where, armed with shovels, the two intended to pay a midnight visit to the local cemetery to surreptitiously determine whether Gein, as legend had it, had disinterred his own mother in the course of his gruesome activities.

Herzog actually made the trip, but Morris had second thoughts and, at the last moment, stood up his new potential colleague. Yet the next year, when Herzog returned to Plainfield to shoot some footage for his film Stroszek, he unexpectedly found Morris there, living in a rented room next to Gein’s old house and conducting interviews with various townspeople, potentially as the basis for a future book or movie project. Despite the younger man’s total lack of filmmaking experience, Herzog invited Morris to join the Stroszek crew, cementing a lifelong, if frequently prickly, friendship between the two. Morris used the modest payment he received for his work to fund another speculative research trip (this time to a town in Florida where insurance companies had identified a suspicious number of locals “accidentally” losing limbs in order to cash in on fraudulent claims) but when the two men’s paths crossed in Berkeley the following year, Herzog learned that Morris had left that idea behind and had embarked on yet another.

This time he had begun doing research for a film on California pet cemeteries—the film that would eventually become his first, Gates of Heaven, and the one around whose realization the famous shoe-eating bet was made. The various characters involved all remember the specifics of the wager differently—in the Blank film, Herzog describes the bet as an attempt to encourage a brilliant if unfocused friend to realize his potential, but in a comprehensive 1989 profile of Morris by Mark Singer in the New Yorker, Luddy remembers the bet as a flippant dare from Herzog, as in, “if you ever manage to actually make a film, I’ll eat my shoe.” Meanwhile Morris, who refused to participate in the film and is conspicuous by his absence from it, tells the New Yorker that the whole thing was nothing more than a publicity stunt cooked up, as it were, by Luddy.

Whatever the genesis, the event—as it unfolds in Blank’s quirky cinematic retelling—begins with Herzog deplaning at San Francisco International on the day of Gates of Heaven’s April 1979 Berkeley debut (it had been shown first at the New York Film Festival a few months earlier) and walking across the tarmac in a pair of worn, brown leather shoes to the tune of an odd, rollicking polka tune called “Old Whiskey Shoes.” Following a sequence in a car during which Herzog muses on the relationship of gastronomy and the cinema—“I’m quite convinced,” he says with a smile at one point, “that cooking is the only alternative to filmmaking,” and later bemoans a recent realization that “for almost a year, I had not cooked a meal,” when “a grown-up man” like him should in fact “not spend a week without having cooked a big meal!”—he ends up at the doorstep of the famed Chez Panisse in Berkeley.

Chez Panisse, a hangout for the movie people at the PFA, also happened to be one of America’s most celebrated restaurants, co-founded by Alice Waters, the hugely influential California chef who began advocating for the joys of fresh local-grown ingredients when the American food industry was still loudly hawking the unlimited virtues of the can, the box, and the freezer bag. In the restaurant’s kitchen, Herzog does the cooking, while Waters points out potential ingredients and serving suggestions. (I spoke to both Waters and her long time Chez Panisse partner Patricia Curtan, and neither had any specific recollections of that afternoon beyond the basic events, although Curtan did recall the whole thing as “a bit of a circus” given that it was going on while the rest of the kitchen staff attempted to prepare the evening’s service. And that the stewing shoe “smelled absolutely horrible.” The recipe, which was obviously nothing more than a spontaneous lark, was never written down, but Cabinet’s crack staff of kitchen testers has reconstructed it, based on the footage in the film. It appears below.)

In the end, the proof of this particularly unpalatable pudding is not so much in the eating as it is in the telling. In the film, Herzog is shown on stage, before a table laid with ketchup, steak sauce, bottles of beer, and a vase full of cut flowers. But he is only seen nibbling a bite or two of the leather, which he cuts from the now slumping boot using poultry scissors—instead, he is focused more on the impromptu lecture he’s giving about the necessity of perseverance in the pursuit of art. Later, backstage, as he gnaws another small mouthful of upper, he is more expansive, connecting the act both to its traditional linguistic meaning and relating it to his own lot as a filmmaker.

“Ever since I have been in contact with audiences,” Herzog says in response to a question by Blank, “I have wondered what the value of films was. I don’t know—it gives us some insight, but it doesn’t change people. … I thought film could cause revolutions or whatever and it does not. But films might change our perspective of things. And ultimately in the long term, it may be something valuable. But there is a lot of absurdity involved as well. As you see,” he continues, gesturing at the glum-looking, half-eaten shoe on the table before him, “it makes me into a clown. And that happens to everyone. Just look at Orson Welles or look at even people like Truffaut—they have become clowns. Because what we do as filmmakers is immaterial. It’s only a projection of light and doing that all your life makes you just a clown. It’s an almost inevitable process. … It’s just embarrassing to be a filmmaker and to sit here like this. But thank heaven I don’t sit here for my own films, but I’m sitting here for a film that was made by a friend of mine. … To eat a shoe is a foolish signal, but it was worthwhile. And once in a while I think we should be foolish enough to do things like that. More shoes!” he laughs, his voice rising. “More boots! More garlic!”

CHAUSSURES CONFIT

Chefs: Werner Herzog & Alice Waters

1 pair ankle-height leather shoes, well-worn

2 heads of garlic

4 red onions

1 bunch fresh parsley

1 bunch fresh rosemary

Hot sauce (preferably a Mexican salsa picante like Cholula or Valentina)

Warm duck fat

Water

Salt

Brush dirt off soles of shoes. Unlace and stuff each inner cavity with a whole head of unpeeled garlic, two peeled red onions, and several bunches of parsley. Season with a dozen or more generous shakes of hot sauce. Reinsert laces and use them to truss shoes. Place the stuffed shoes in a large metal pot. Add equal parts liquid duck fat and hot water to cover shoe tops. Add up to a dozen whole sprigs of rosemary and additional hot sauce if desired. Salt to taste. Cook over moderate heat for approximately five hours.

Serve, per Waters’s suggestion, as one would “a pig’s foot, with something like beans and chili and lots of onions sprinkled on top and a little raw garlic and some spices like oregano or more rosemary.” Or, as Herzog actually does, straight from the pot in front of an audience, with the somewhat more pliant uppers cut into pieces with poultry scissors and washed down with cold beer and the soles discarded, because, as the director notes, “when you eat a chicken you leave the bones away.”

Adapted from Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, 1979

Jeffrey Kastner is a Brooklyn-based writer and senior editor of Cabinet.