The Cosmonaut of the Erotic Future

A brief history of levitation from St. Joseph to Yuri Gagarin

Aaron Schuster

What happens to levitation, one of the great imaginative figures of art and literature, in the transition from a religious culture to the disenchanted universe of modern science? What becomes of ecstasy, rapture, ascension, transcendence, grace when these give way to “space oddity”: man enclosed in a tin can floating far above the world? Is the cosmonaut a prophet of the erotic future, avatar of man’s stellar renaissance, as Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke once imagined? Or is he like Nietzsche’s madman, proclaiming as Gagarin himself was rumored to have said: “I don’t see any God up here”?

Levitation derives from the Latin levitas, meaning lightness. The term would appear to have been coined as the opposite of gravitation, sometime in the early seventeenth century when humanity’s conception of the cosmos was being revolutionized by Brahe, Copernicus, and Kepler. Rather than being based on qualitative “elective affinities,” the attraction of bodies became a matter of purely quantitative relations expressed by algebraic symbols. Though the ancient cosmology was effectively vanquished by the new clockwork universe, this was hardly a simple or straightforward affair. Even Sir Isaac Newton hedged his bets. While developing his theory of gravitation, Newton was also privately elaborating a highly idiosyncratic theology. According to certain obscure and, until recently, largely neglected writings, after the Apocalypse “children of the resurrection” (notably Newton himself) would be able to levitate at will, soaring “to the furthermost extremities of the universe.”[1]

Levitation is also related to levity, to the lighthearted, the frivolous, and the fun. The link between levitation, levity, and laughter was made explicit in the 1964 Walt Disney classic Mary Poppins. (As we’ll see, the 1960s was an absolutely crucial decade for levitation.) Near the end of the film, the curmudgeonly bank director miraculously ascends as he goes into hysterics at an employee’s little joke. I won’t tell you the joke—it’s not very good. Later we learn that the old man died. But he died happy from levitating laughter.

Cendrars ends the first part of the book with a passionate proposal to make a film about the levitating saint: “If a producer ever feels like making this prodigious film, I—I, who have sworn never again to waste my time making films—will drop everything, give up my solitude, my tranquility, and my writing, to make this film about St. Joseph of Copertino, in memory of my son, Rémy, the pilot, and as a souvenir for his sometime girlfriend, the out-of-work baker’s girl, with whom I lost touch in wartime Paris.”[2]

In order to envision the appropriate kitsch aesthetics for our hypothetical comedy, we need look no further than The Flying Nun, a highly eccentric television series that ran from 1967 to 1970. No history of levitation would be complete without mentioning this program. The show centered on the adventures of a group of nuns in the Convent San Tanco in Puerto Rico. Sister Bertrille could be counted on to get the nuns out of any jam by virtue of her unexplained ability to fly (perhaps it had to do with the aerodynamics of her oversized hat). Of course the storylines were limited—there are only so many situations one can devise that require the heroine to levitate—and so the show was cancelled after three seasons.

As it happens, a film was made about the life of St. Joseph. It is titled The Reluctant Saint and was released in 1962. The movie was directed by Edward Dmytryk, who is best known for The Caine Mutiny and for being one of the “Hollywood Ten.” It is very difficult to get hold of a copy of this film. I have seen it and can report that it is rather conventional and dull. Yet with Ricardo Montalban playing the suspicious Father Raspi, and the great Maximilian Schell in the role of St. Joseph, it is still definitely worth a view.

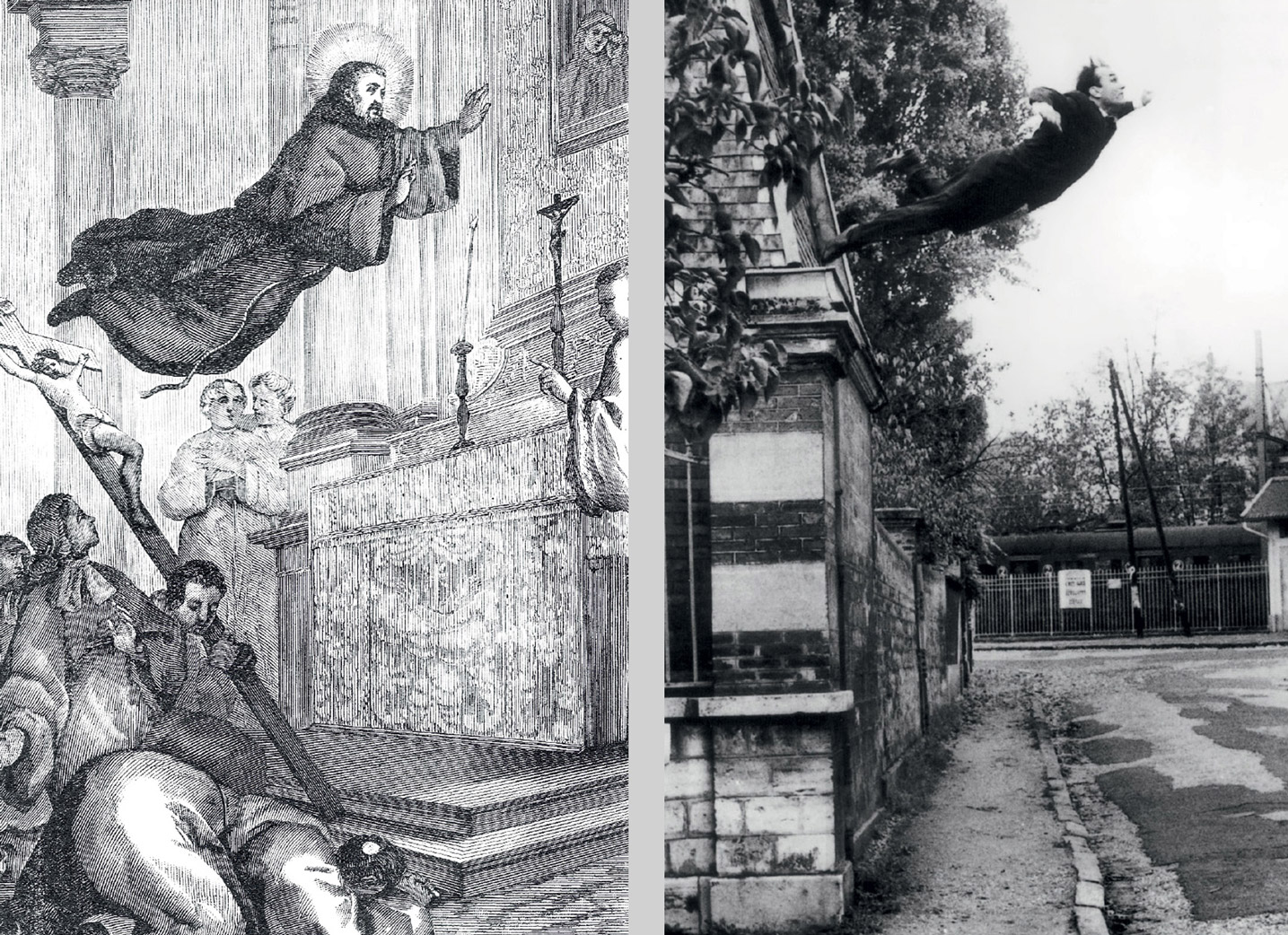

This ideal, which is simultaneously that of the artist, the artwork, and life itself, is embodied in Klein’s iconic photograph The Leap Into the Void; its other, lesser known title is Obsession of Levitation. The artist’s audacious plunge is that of a saint announcing the dawn of a new era,[4] an epoch of immateriality where buildings will be fashioned from air currents, color dissolved into the void, and life and art merged in blissful union. In the caption beneath the photograph, it is written: “Today the painter of space must, in fact, go into space to paint, but he must go there without trickery or deception, and not in an airplane, nor by parachute, nor in a rocket: he must go there on his own strength, using an autonomous, individual force; in short, he must be capable of levitation.”[5] With his leap, Klein both anticipates the space flight of Yuri Gagarin and outdoes him. The artist is superior to the cosmonaut in that his journey into space is made without the aid of technological gadgetry. Of course, it is ironic that The Leap Into the Void is precisely a doctored photograph, an early and masterful example of image manipulation before the days of Photoshop. As much as it may aspire to “True Life,” art, after all, remains a matter of illusion. The photograph was staged on 19 October 1960, with Klein’s judo pals holding a blue sheet to catch the levitating artist. It appeared soon after in the publication Dimanche 27 novembre. Le Journal d’un seul jour (Sunday 27 November: Newspaper of a Single Day).

If the classical ideal of art is a kind of elevation, lifting up or spiritualization, one way of characterizing contemporary art is as an “art of the fall.”[6] Rather than the miraculous flight of the saint, its iconic figure is the well-timed tumble of the slapstick artist. In short: Buster Keaton in place of St. Joseph. I am thinking especially of Bas Jan Ader’s Fall films, but there are many failed levitations in recent art history. After hearing about The Leap Into the Void, Paul McCarthy reportedly jumped from his balcony—and broke a leg. There should be a name for this kind of vertiginous mimetic behavior. Perhaps after the Stendhal syndrome, we could call it the Klein syndrome.

How does the analyst interpret Gagarin’s voyage? Lacan paints a vivid portrait of the cosmonaut as living pulp implanted in a tin can, quivering flesh plugged into a complex technological apparatus. If for Freud man had already become a “prosthetic God,”[7] in the era of the cosmonaut he would seem to be relegated to a button pusher, utterly dependent on the machine that supports his life functions and extends his limited sensorium. Gagarin himself, together with Soviet psychologist Vladimir Lebedev, stated plainly: “The main function of the operator in the ‘man-machine’ system, provided it functions normally, is to take the reading of instruments.”[8]

For Lacan, the precarious situation of the cosmonaut hooked into an impenetrable mechanism is not an isolated or extreme case, but reveals the universal condition of the human subject. We are all erotic cosmonauts, split between our everyday, phenomenological life experience and the computing apparatus—what Lacan calls the “symbolic order”—that parasites our body and secretly controls our thoughts and desires. The lot of the modern subject, adrift in a universe of significations without substantial support or foundation, is perfectly encapsulated by “the experience of the cosmonaut: a body that can open and close itself weighing nothing and bearing on nothing.”[9]

What does space flight signify for the Jewish philosopher? The first thing that strikes the eye is the way that Levinas puts Gagarin and Heidegger back to back. Strange comparison: what do the Russian cosmonaut and the rustic thinker of Todtnauberg have to do with one another? In fact, they represent absolute antipodes: Soviet Communism and German Fascism, technological wizardry and technophobic anti-modernism, vita activa and vita contemplativa. Most importantly, for Levinas this impossible couple stands for the choice between “enlightened uprootedness” (enracinement éclairé) and “earthly attachment” (attachement terrestre). By voyaging into space, man leaves behind his mythic homeland: even further, he discovers that this hallowed place was never anything but superstition and idolatry. Levitation makes of the human being a creature of the universe. Against the philosopher of the forest clearing, Levinas defends the astral desires of technological man.

To quote Levinas’s remarkable elegy to Gagarin in full:

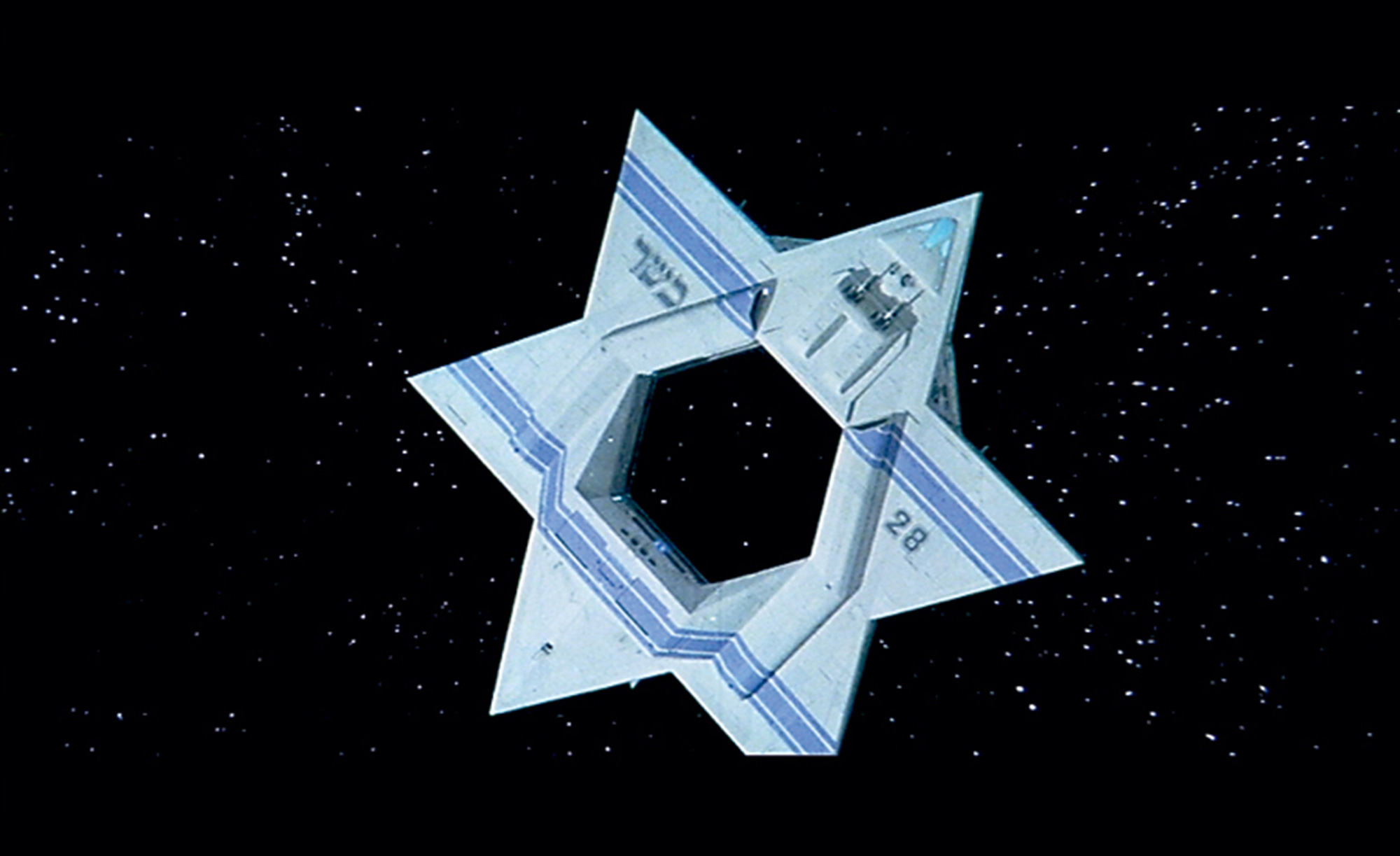

What is admirable about Gagarin’s feat is certainly not his magnificent Luna Park performance which impresses the crowds; it is not the sporting achievement of having gone further than the others and broken the world records for height and speed. What counts more is the probable opening up of new forms of knowledge and new technological possibilities, Gagarin’s personal courage and virtues, the science that made the feat possible, and everything which that in turn assumes in the way of abnegation and sacrifice. But what perhaps counts most of all is that he left the Place. For one hour, man existed beyond any horizon—everything around him was sky or, more exactly, everything was geometrical space. A man existed in the absolute of homogeneous space.[14]In brief, Gagarin is the ultimate figure of exile: a man without roots in a cosmic desert without horizon or end. Mel Brooks once made a comedy sketch called “Jews in Space,” but Levinas goes even further: in the vast expanses of space, we are all wandering Jews.

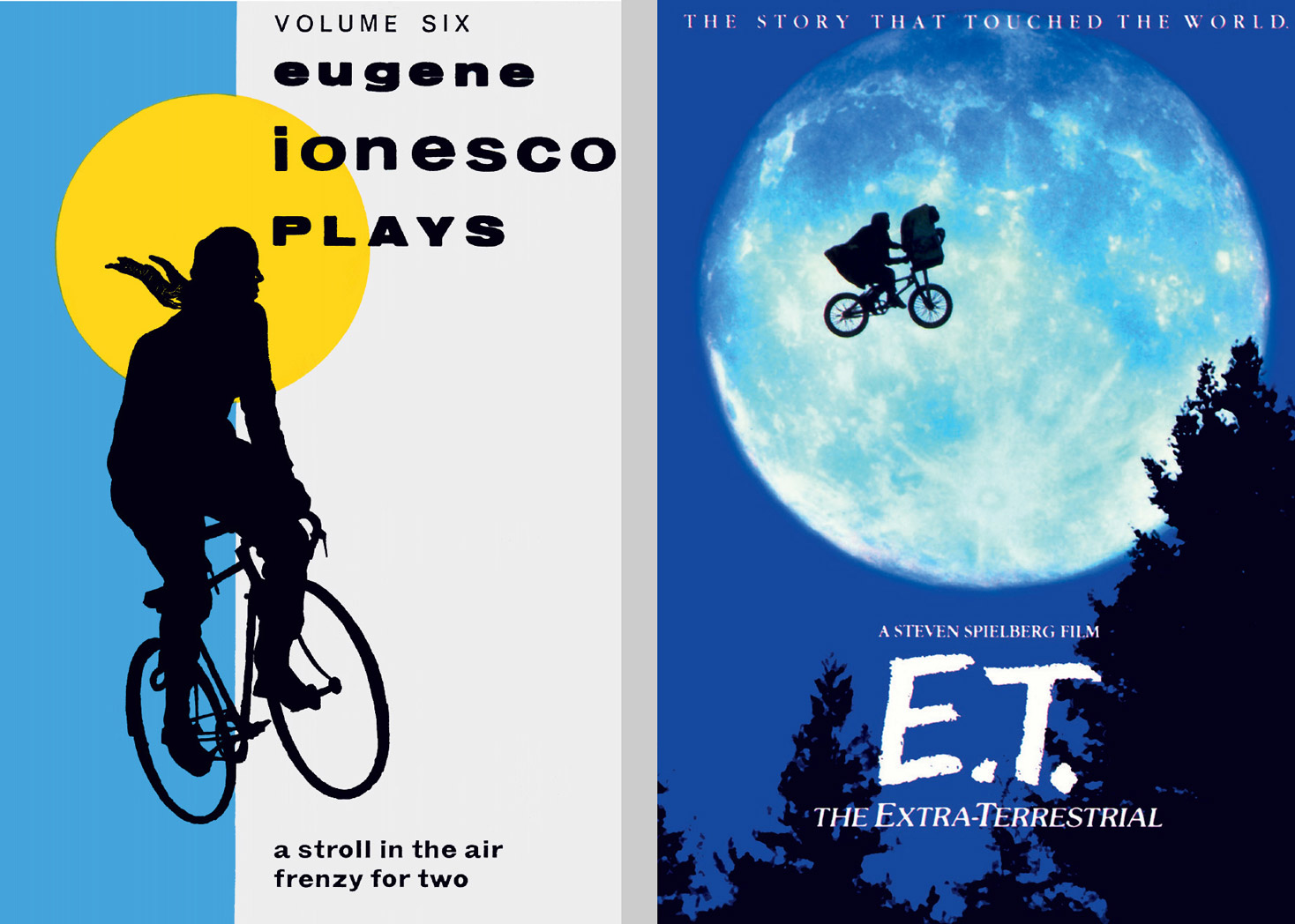

The historian of levitation cannot fail to be impressed by the different ways in which levitation is posited as universal destiny. Who is the cosmonaut of the erotic future? Is he the soaring angel of ecstasy that augurs the coming of paradise on earth? Is he the machinic apparatus that parasitizes our body and controls our deepest desires? Or is he the geometric prophet of a new interstellar Diaspora? One of Eugene Ionesco’s lesser-known plays, A Stroll in the Air, first performed on 15 December 1962 (a little more than one month after the release of Dmytryk’s film on St. Joseph), suggests that salvation lies in reclaiming our innate levitative powers. When Monsieur Bérenger rises into the sky one Sunday afternoon, he explains his behavior to dubious onlookers thus: “Man has a crying need to fly. ... It’s as necessary and natural as breathing. ... Everyone knows how to fly. It’s an innate gift but everyone forgets.”[16] The same sentiment was later echoed in Paul Auster’s Mr. Vertigo. At the novel’s end, the narrator, once a vaudevillian “Wonder Boy” renowned for his gravity-defying stunts, offers the following simple instructions for levitation:

Deep down, I don’t believe it takes any special talent for a person to lift himself off the ground and hover in the air. We all have it in us—every man, woman, and child—and with enough hard work and concentration, every human being is capable of duplicating the feats I accomplished as Walt the Wonder Boy. You must learn to stop yourself. That’s where it begins, and everything else follows from that. You must let yourself evaporate. Let your muscles go limp, breathe until you feel your soul pouring out of you, and then shut your eyes. That’s how it’s done. The emptiness inside your body grows lighter than the air around you. Little by little, you begin to weigh less than nothing. You shut your eyes; you spread your arms; you let yourself evaporate. And then, little by little, you lift yourself off the ground. Like so.[17]

This essay is adapted from a talk given as part of the night program of the Berlin Biennial (“Mes nuits sont plus belles que vos jours”) in the Zeiss Planetarium, Berlin, on 4 May 2008.

- Frank E. Manuel, The Religion of Isaac Newton (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), p. 102. I also draw here on Joel D. Black, “Levana: Levitation in Jean Paul and Thomas de Quincey,” Comparative Literature, vol. 32, no. 1 (Winter 1980), pp. 44–45.

- Blaise Cendrars, Sky Memoirs, trans. Nina Rootes (New York: Paragon House, 1992), p. 148. The other great writer of the twentieth century fascinated with St. Joseph was Italian playwright and actor Carmelo Bene, who wrote a whole play about the flying priest. For Bene, the most interesting characteristic of St. Joseph was his imbecility—he quips that Joseph was so stupid he didn’t even know the law of gravity.

- Yves Klein, “Overcoming the Problematics of Art,” in Overcoming the Problematics of Art, trans. Klaus Ottmann (Putnam, CT: Spring Publications, 2007), p. 64. Translation modified.

- The suspended pose of the self-defenestrating artist might best be described with the paradoxical expression of an “upwards fall.” As Cendrars writes: “The saint who falls into ecstasy falls into the abyss, floats On High, levitates, gyrates in a transport, breaks out, and is no longer in possession of himself. At the most, he lets out a cry or a last sigh. Then he lets himself go and plummets into the very depths of the Word of God. He soars…” See Cendrars, Sky Memoirs, p. 135.

- Klein, “Selections from ‘Dimanche,’” in Overcoming the Problematics of Art, p. 106.

- See Gérard Wajcman, “Desublimation: An Art of What Falls,” Lacanian Ink, no. 29 (Spring 2007).

- Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey (London: Hogarth, 1955) vol. 21, pp. 91–92.

- Yuri Gagarin and Vladimir Lebedev, Psychology and Space, trans. Boris Belitsky (Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2003), p. 259.

- Jacques Lacan, “Merleau-Ponty: In Memoriam,” in Merleau-Ponty and Psychology, ed. Keith Hoeller, trans. Wilfried Ver Eecke and Dirk de Schutter (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1993), p. 74. Translation modified.

- Lacan, Seminar IX, L’Identification, session of 28 February 1962 (unpublished).

- For the father of psychoanalysis, the paradigmatic levitating object is the phallus. “The remarkable phenomenon of erection,” Freud writes, “around which the human imagination has constantly played, cannot fail to be impressive, involving as it does an apparent suspension of the laws of gravity.” The Interpretation of Dreams, in Standard Edition, vol. 5, p. 394. Freud’s colleague Victor Tausk adds that erection is first experienced as “an exceptional and mysterious feat,” something “independent of the ego, a part of the outer world not completely mastered,” and even a kind of “machine subordinated to a foreign will.” See “On the Origin of the ‘Influencing Machine’ in Schizophrenia,” in Sexuality, War, and Schizophrenia: Collected Psychoanalytic Papers, ed. Paul Roazen (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1991), pp. 213–214.

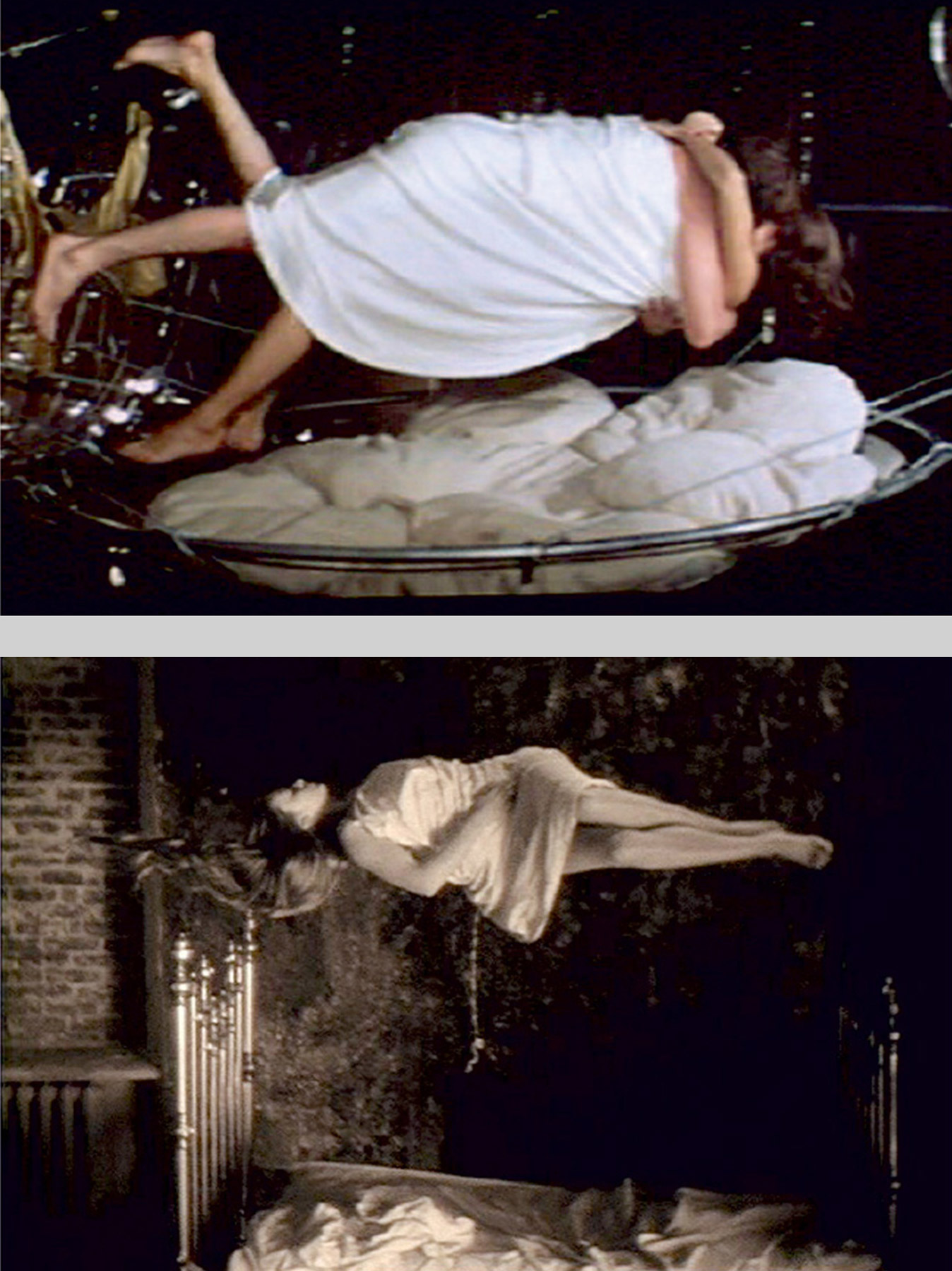

- In contrast, in the cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky, levitation always occurs in place of the sexual act. By virtue of its unreal, miraculous character, levitation is apt to convey the miracle of love, which, according to Tarkovsky, is completely obscured by images of copulating bodies. Incidentally, it was another Soviet filmmaker, Pavel Klushantsev, who first filmed zero-gravity space scenes.

- One should not forget, however, the mystical tradition of Judaism, which includes flying rabbis; see, for example, the floating Jews in Cynthia Ozick’s short story “Levitation,” or scenes of flight in the paintings of Marc Chagall. Like Judaism, official Islam also de-emphasizes levitation. One of the most interesting treatments of levitation in the Islamic tradition is found in the work of Avicenna, who, some six centuries prior to Descartes, proposed a radical thought experiment to demonstrate the nature of self-consciousness. This experiment, in which a man is imagined deprived of sense data, floating in a void, was later dubbed the “Flying Man.”

- Emmanuel Levinas, “Heidegger, Gagarin and Us” in Difficult Freedom: Essays on Judaism, trans. Seán Hand (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), p. 233.

- Samuel O. Poore, “The Morphological Basis of the Arm-to-Wing Transition,” The Journal of Hand Surgery, vol. 33 (February 2008). I thank Darius Miksys for this reference.

- Eugene Ionesco, “A Stroll in the Air,” in Plays, vol. 6, trans. Donald Watson (London: John Calder, 1965), pp. 46–47.

- Paul Auster, Mr. Vertigo (New York: Penguin, 1994), p. 293.

Aaron Schuster is a writer based in Brussels. He has lectured and published widely on psychoanalysis and contemporary philosophy, and his writings on art have appeared in Frieze, Frog, Metropolis M, and De Witte Raaf. He coauthored the libretto for Cellar Door: An Opera in Almost One Act (JRP Ringier, 2008), and his Cosmonaut of the Erotic Future: A Brief History of Levitation from St. Joseph to Yuri Gargarin will appear as a book in 2009.