A Little Etymological Test

Keep your eye on the balls

Joshua T. Katz

A quip, told to me long ago by a friend who adopted a Peter Lorre-like accent and leered at me as a mad teacher might at his students: “If you like my little quizzies, wait till you see my big testies.”

Does size matter? It did for the Chinese who sat the imperial examinations, which stretched over several days. And it does today in the United States: 2400 on the SAT (no longer an acronym now that it is apparently deemed neither a Scholastic Assessment nor a Scholastic Aptitude Test) is the new 1600; scores have been “recentered” upward, as a way of compensating for lower average results; and there is in the writing section a correlation—embarrassingly independent of quality—between length and grade, as MIT professor Les Perelman pointed out a few years back. (At the time, at least, the official guide for scorers blithely stated, “Writers may make errors in facts or information that do not affect the quality of their essays. For example, a writer may state … ‘“Anna Karenina,” a play by the French author Joseph Conrad, was a very upbeat literary work.’”) Not readers of big books, aside from Harry Potter, Americans are, nonetheless, a nation of test-takers, as Elizabeth Alexander reminded the world transfixed by Barack Obama’s inauguration, describing in her poem “Praise Song for the Day” how “A teacher says, Take out your pencils. Begin.”

The swarms of students who take out their #2 Faber-Castells—the main definition of the Latin word examen is “swarm (of insects),” though our examination comes from the other sense, related to the multivalent verb exigere, which can mean “to examine”—no longer have to deal with analogies on the SAT, so gone are the days of quiz : test :: pamphlet : X, where X = (a) tome; (b) zygote; (c) magazine; (d) exiguous; or (e) epitome. The College Board explains that “analogy questions have been removed because they are less connected to the current high school curriculum.” (Also removed is the connecting hyphen [from Greek, ὑφ’ ἕν, “in one”] in “high-school curriculum,” but since it’s not there in High School Musical either, it seems safe to assume that hyphenation, too, is “less connected.”) No students will henceforth scratch their heads over quiz : quizzes :: test : X.

The word test, which in its earliest uses in English refers to a cupel, is a borrowing from an Old French word for “pot” that itself goes back to a variant of Latin testa, “earthenware jar; potsherd; hard outer covering of (e.g.) a crustacean.” (The deeper background of testa is unknown.) A portable hearth, the cupel is used in assaying—that is to say, testing—alloys of precious metals. It is often made of bone ash and looks a bit like an upside-down skull: the semantic sidle from testa to French tête (“head”) finds English analogues in our mug (shot) and in the compounds jughead (think of Archie’s girl-disdaining, hamburger-eating friend) and jarhead (a Marine). Admittedly, the meaning of pothead is a different matter.

Let us scratch our heads over quiz : quizzes :: test : X anyway. Broadly speaking, the etymology of testes (singular testis) and its morphologically well-hung diminutive testiculi (singular testiculus, whence our testicle) is in one respect known and in another disputed. Clear is that testis meant in the first place “witness,” as in the legal dictum unus testis, nullus testis (“one witness [is] no witness”), a view expressed in a language other than Latin in Deuteronomy: “One witness shall not rise up against a man for any iniquity, or for any sin, in any sin that he sinneth: at the mouth of two witnesses, or at the mouth of three witnesses, shall the matter be established.” Not clear, however, is how Latin came to find itself in the position of having two apparently quite different meanings of testis, namely both “witness” and “testicle.” To quote the title of a short, sweet, but linguistically maladroit article by three urologists from Portsmouth in a 2002 issue of the British Journal of Urology International, “The testis: what did he witness?”

Unlike with testa, the deeper background of the primary meaning of testis is known and is, indeed, a testament to etymological method: testis once had an r in it (compare trstus in the closely related Oscan language) and was transparently a compound, whose Proto-Indo-European preform is reconstructed by linguists as *trito-sth2-o, literally “standing (Latin sto, ‘I stand’) as third (tertius).” But why would a bystanding witness also become a testicle, except to give Roman wags such as Plautus (the inspiration behind A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) endless opportunities to engage in what a gym teacher of mine once referred to as “low ball games”?

It turns out that it is cross-culturally common for people—let me say men—to manipulate genitalia—let me stress others’—during the swearing of oaths. In Genesis, Abraham’s servant swears with his hand “under the thigh” of his master, and some chapters later, Joseph puts his hand under his father Jacob’s “thigh.” An eighteenth-century BC Old Babylonian letter from the city of Kisurra (in present-day Iraq) includes the words, “Thus you (have said to me): ‘Let your envoy grasp my testicles and my penis, and then I will give (it) to you.’” Hindu and Arabian pledges of honor from the eighteenth century AD and beyond in which men hold each other’s private parts are described in graphic detail by the orientalist and sexologist Allen Edwardes. Somewhat differently, in Athenian homicide trials, the accuser trampled the testicles of a boar, a ram, and a bull, swearing to the veracity of his claim and invoking destruction on himself and his family if he was perjuring himself. These are serious oaths: one possible implication of holding onto (or standing on) testicles is that the bearing of false witness may call down a curse upon not only oneself but one’s house and future line.

Can you use your own testicles for testimonials? You might think so, but strangely, there does not appear to be a lot of evidence for such a practice. This has, however, not stopped some people from imagining colorful scenarios: “When a man swore something was true, giving testimony, he put his hands on his testicles. In effect, he was saying: You can cut off my balls if I’m lying. In time, law courts decided that asking a man to put his hands on the Bible might be more decorous” (Diane Ackerman, in A Natural History of Love). Still, Italian men even today do give themselves quick grabs with the words io mi tocco i … (“I touch my …”); the equivalent of our touch (or knock on) wood, this gesture was ruled a criminal offense by Italy’s highest appeals court in early 2008.

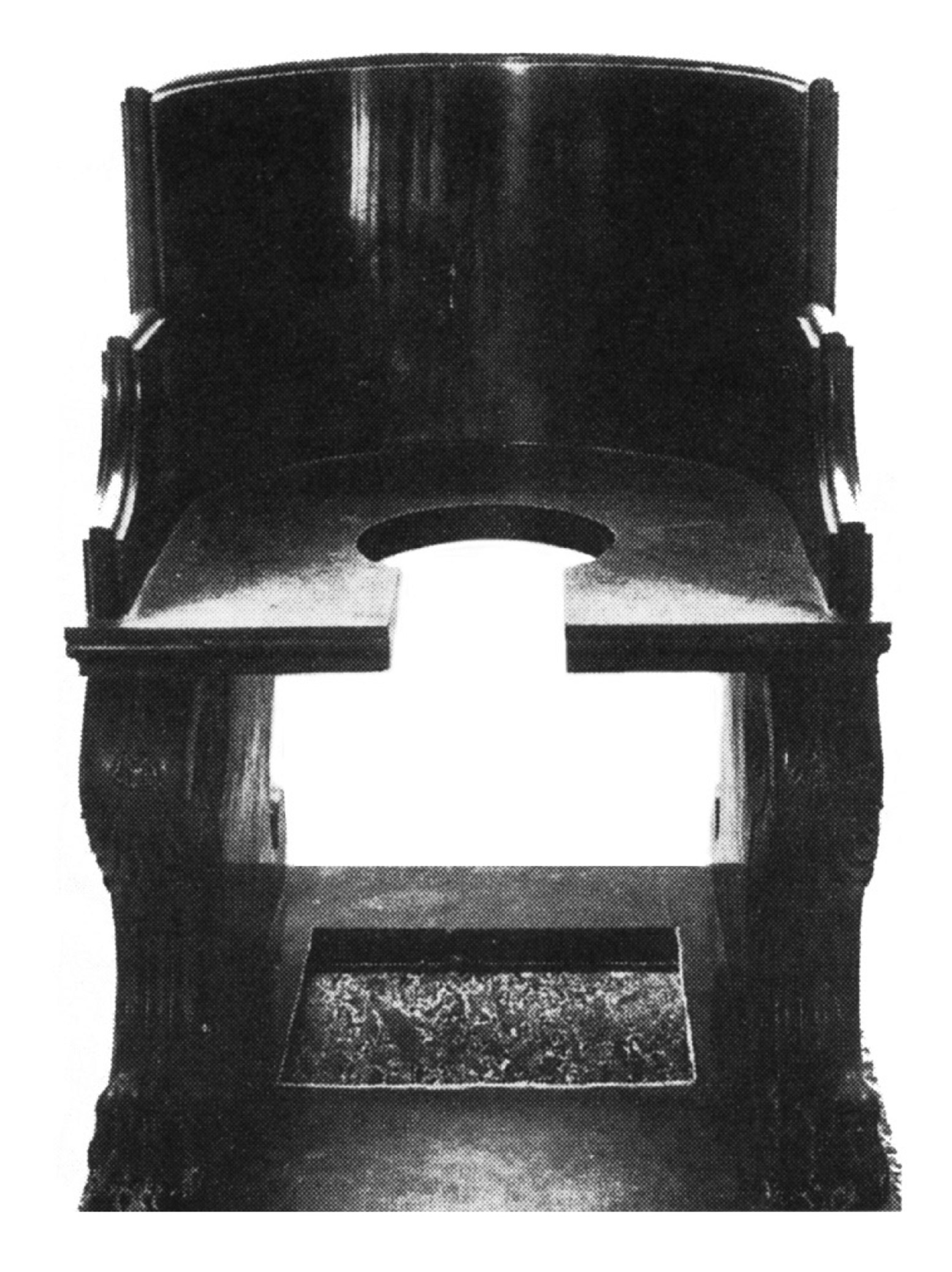

Can women swear testicular oaths? Consider the historian Huw Pryce’s description of the following scene from medieval Wales, where oaths were commonly sworn on holy relics: “a woman who persisted in accusing a man of having raped her after his initial denial was required to repeat the charge on oath while holding the relic in her right hand and the man’s penis in her left.” Some readers will now think of the widespread belief that the pierced chairs, such as the famous sedes stercoraria (literally “shit seat”) at the Lateran, were introduced in the aftermath of the papacy of “Joan” to allow for a functionary to grope the Pope and attest to his worthiness by crying out, testiculos habet (“He has testicles!”).

This is an urban legend. (Remember that the Eternal City is the urbs, from which the Pope addresses the “Urbi et Orbi.”) To back up the connection between witnesses and testicles in ancient Rome itself, we have only a hermeneutically difficult passage about mnemotechnics in the rhetorical handbook Ad Herennium, once upon a time attributed to Cicero, in which a lawyer is advised to keep in mind a picture of the defendant testiculos arietinos tenentem (“holding a ram’s (or rams’) testicles”) so as to remind himself that there were witnesses to the crime.

Unus testiculus, nullus testiculus? I like to think that the shift in Latin from “witness” to “testicle” is no longer as peculiar as it seems at first glance, but rests on a robust cultural institution. For details, lay your hands on my papers in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 98 (1998) and Journal of Indo-European Studies 34 (2006). And criticize them, if you wish. Plenty of other people have done so, most recently Lochlan Shelfer in volume 69 (2009) of a journal I’m happy to say I don’t (yet) regularly check out: The Prostate. I expose myself to you, dear reader, and await my test score.

But to come full circle, what about test? When you attest to and testify to and give testimony of your knowledge on a little quiz or a big test, you are using your head, not your cojones. When, however, you attest to and testify to and give testimony of your knowledge in court, it’s the other way around: your nuts are doing the talking, not your nut. Or at least that’s the case from an etymological point of view. And since the Greek-derived term etymology refers etymologically to “true (etymos) speech (logos),” shouldn’t you take my word for it?

Joshua T. Katz is professor of Classics and director of the Program in Linguistics at Princeton University. He is particularly interested in etymology, which he views as part of the history of ideas. This fall, he will be teaching a freshman seminar on the history and practice of wordplay.