They Rode the Rockets

Animals in space

Colin Burgess

Before achieving lasting fame as America’s first man in space in May 1961, Mercury astronaut Alan Shepard was asked why he had been selected to make the historic flight. He grinned and responded, “I guess they just ran out of monkeys!”

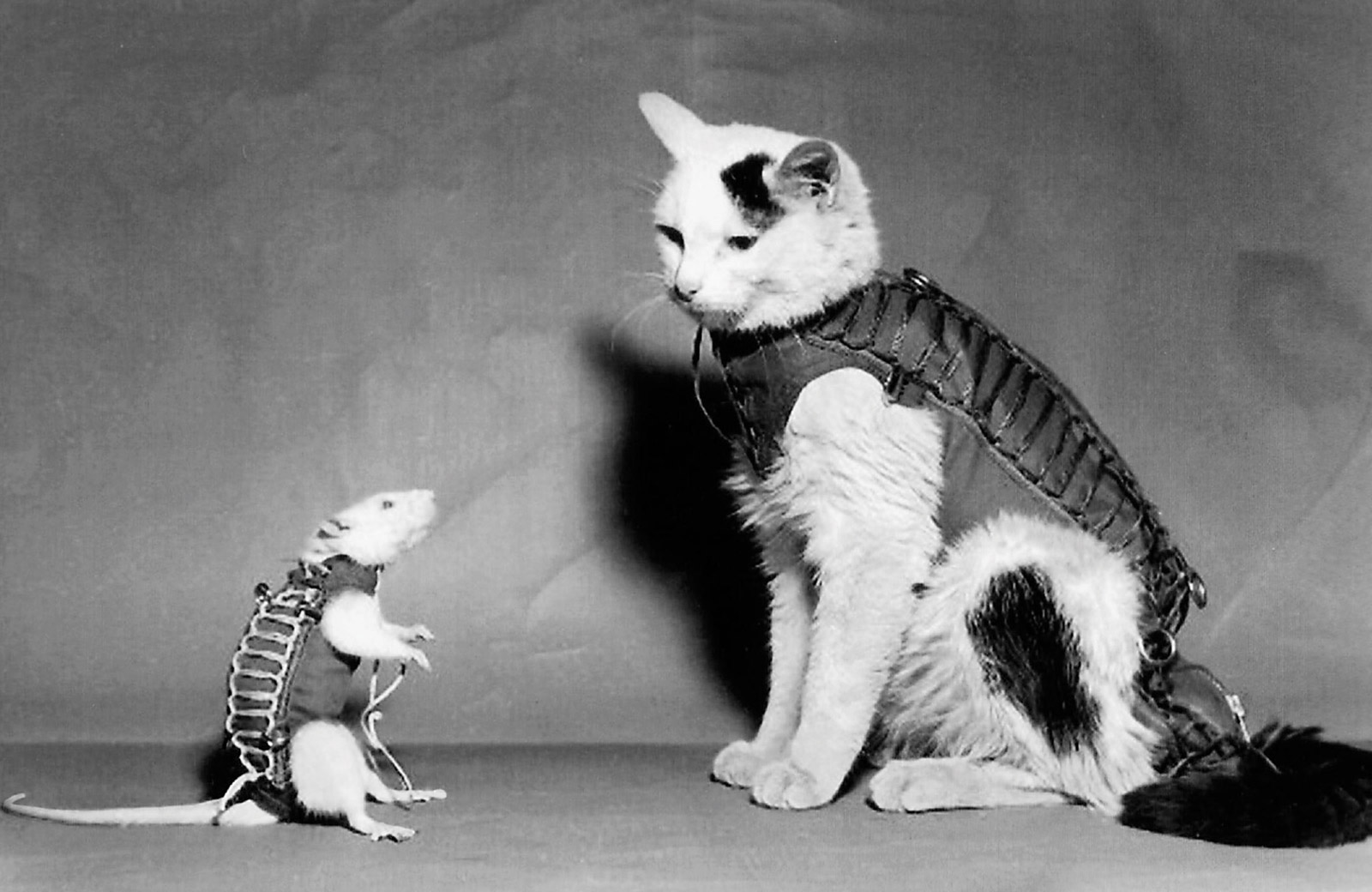

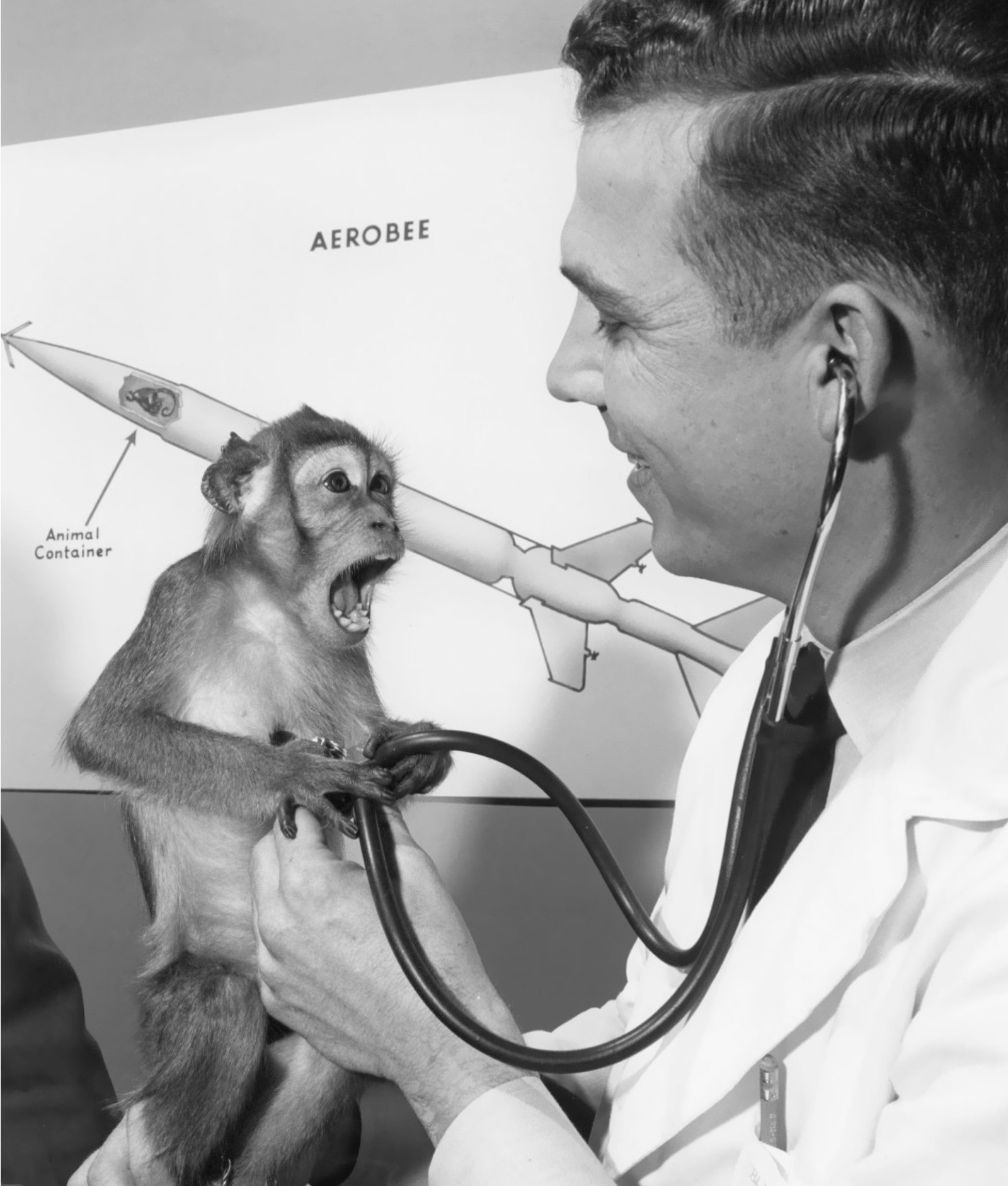

Shepard was not simply being self-deprecating. In the late 1940s, when the US and the Soviet Union began military ballistic test flights using captured German V-2 technology, the high-altitude flights also carried animals in order to determine whether humans could eventually survive a rocket launch and the expected disorientation caused by weightlessness. American stratospheric test flights carried a series of monkeys as “simulated pilots.” The first six of these animals perished, primarily due to parachute failure. It was four years into Project Blossom before two macaque monkeys named Patricia and Michael became the first animals to survive a US rocket flight, reaching an altitude of thirty-nine miles in May 1952.

Soviet scientists, meanwhile, preferred small dogs as their test subjects and set about gathering hardy candidates from the streets of Moscow. These dogs were tough, inured to hunger and cold, and therefore considered suitable for the rigors of training and space flight. The first series of high-altitude flights carried a total of eight dogs aboard modified V-1 rockets in 1951; only half survived the ordeal.

In October 1957, the Soviets launched the first satellite, Sputnik, into space. The following month, a tiny terrier named Laika (“barker”) was hurled into orbit aboard Sputnik 2. The Soviets, however, had not developed a satellite recovery system, and the first animal cosmonaut was predestined to perish in space. As it happened, Laika died from heat prostration within hours of launch, when a loss of insulation during staging created unsustainably high temperatures within the satellite. Three years later, in August 1960, a pair of Soviet dogs named Belka and Strelka (accompanied by thirty-four mice and two rats) achieved global fame as the first animals successfully recovered from orbit. Other canine orbital flights successfully took place before a small dog called Zvezdochka flew in March 1961. This final test of the spacecraft’s systems in orbit paved the way for Yuri Gagarin to achieve humankind’s first space flight just two weeks later.

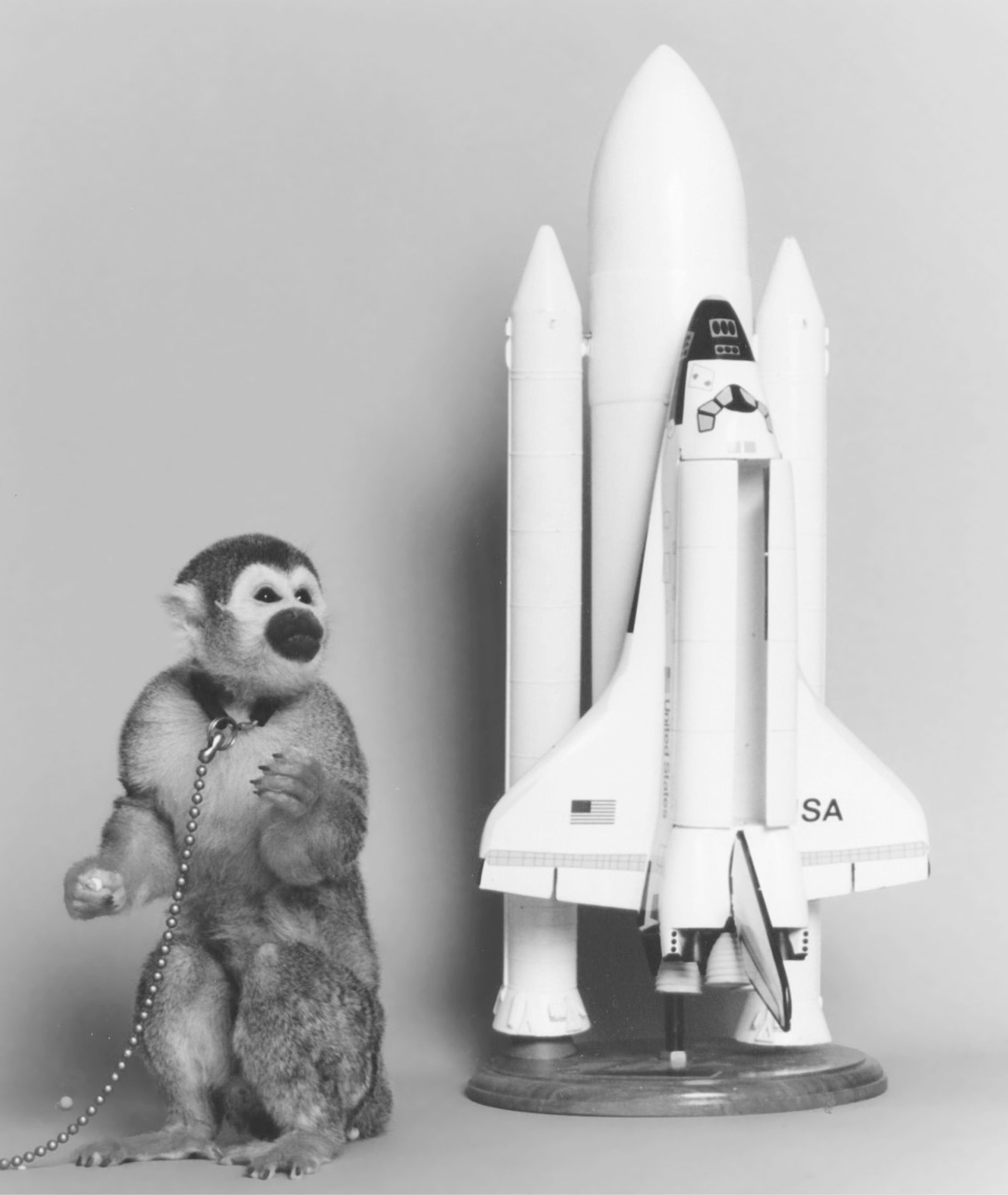

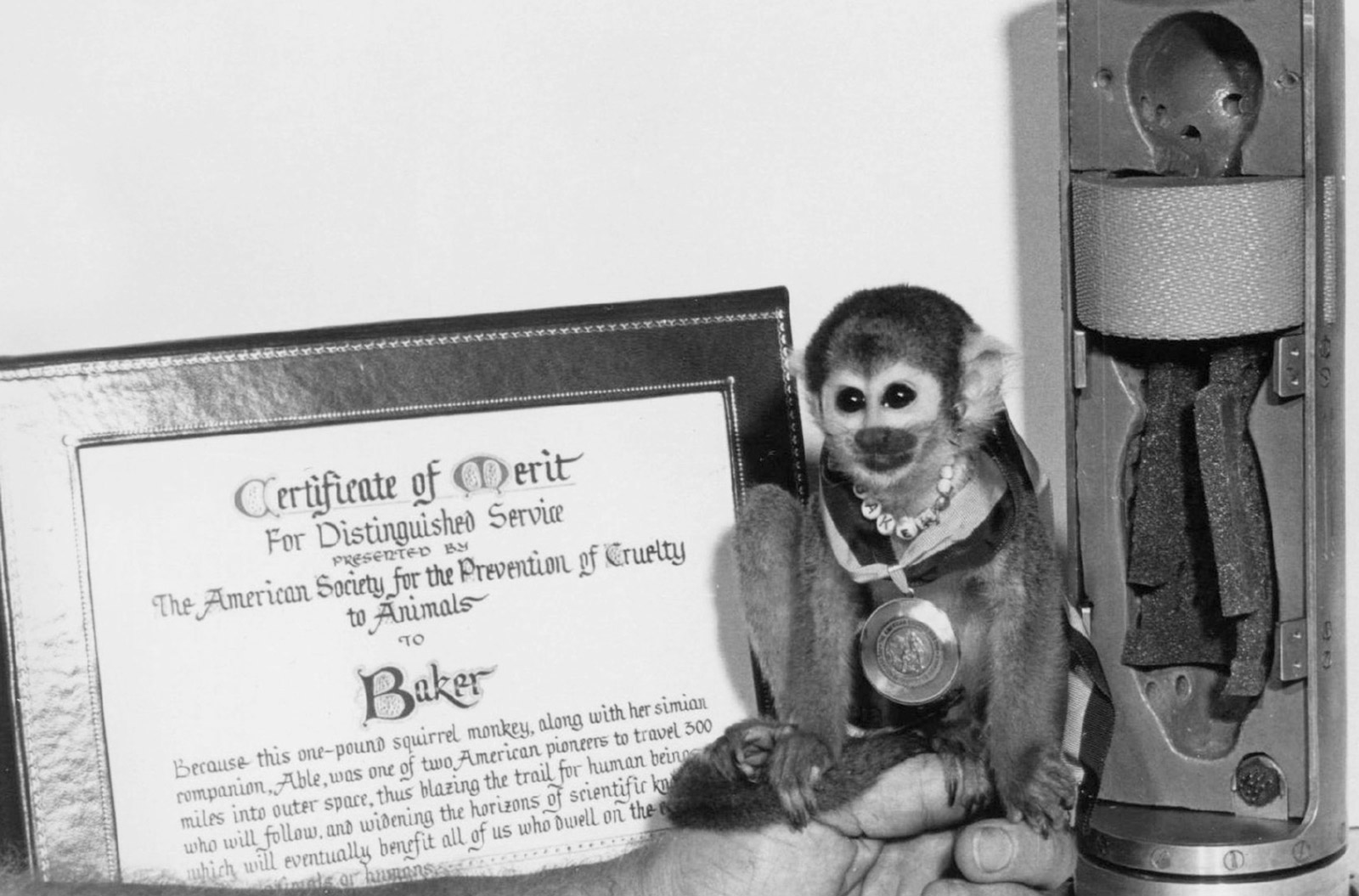

After a six-year hiatus, America would resume bioflight operations on Friday, 13 December 1958, when a Navy-trained squirrel monkey named Gordo was launched aboard a Jupiter ballistic missile. Gordo survived the nine minutes of weightlessness, but perished when her spacecraft sank after splashdown in the South Atlantic. Traditionally, no Navy ship is launched on Friday the 13th, and it seems poor Gordo fell afoul of that particular superstition. Redemption would come on the next Jupiter launch, which carried a female rhesus monkey named Able and a female squirrel monkey named Baker 360 miles into space on 28 May 1959. Following their successful recovery at sea, a Navy diver opened the small container holding the squirrel monkey and was rewarded with a good, solid bite on the arm. Miss Baker, as she came to be known, lived to become a true celebrity of the space age, appearing in countless publications and gracing the cover of Life magazine. Able fared less well: she died four days after splashdown under anesthetic as doctors removed sensors implanted beneath her skin.

Despite the success of the Jupiter mission, NASA wanted more data prior to sending the first American into space, and decided to test the Mercury spacecraft and its Redstone rocket on a precursory suborbital flight with a chimpanzee taking the place of an astronaut. On 31 January 1961, Ham soared into spaceflight history with a perfect launch from Cape Canaveral, clearing the way for Alan Shepard to follow. A similar scenario preceded the orbital flight of astronaut John Glenn, when a feisty chimp named Enos completed a two-orbit mission. It was then judged safe to launch Glenn on his own historic mission.

As late as 1985, two squirrel monkeys were launched aboard space shuttle Challenger to test the effects of prolonged space flight, research that had originally begun in the 1960s when the Soviets sent two dogs through the Van Allen radiation belt. Up until 1996, the two countries, now partners in space, carried out a series of joint biosatellite flights. All the monkeys involved survived, but animal activist groups successfully petitioned for the termination of any future flights involving primates.

Colin Burgess is an Australia-based spaceflight historian. His numerous publications on the subject include Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle (Springer-Praxis, 2007), co-authored with Chris Dubbs.