Drawing Out Your Mind

A sampler of projective psychological tests

Sina Najafi and Christopher Turner

We live in a culture so saturated with tests—administered by schools, corporations, the military, and hospitals, amongst others—that we have come to believe that we can only know ourselves through the mechanics of examination. Every one of us leaves a paper trail of test results that places us in a hierarchy and enables us to be judged against a predetermined norm.

With the invention of psychoanalysis, a new tool emerged for measuring personality—“the projective psychological test,” in which an individual is invited to project meaning onto ambiguous visual stimuli. Unlike “objective psychological tests,” which are normally multiple-choice, projective tests assume the existence of an unconscious mind. Through their responses, the test subjects are believed to reveal their hidden impulses and desires.

By far the best-known projective test is the one created in 1921 by Hermann Rorschach (1884–1922), a Swiss psychologist working at the institute and asylum of Herisau. Interest in inkblots, however, long preceded Rorschach. In the visual arts, Leonardo da Vinci and Victor Hugo were early experimenters with the technique, and in 1857 Justinus Kerner published Kleksographien, a book of inkblot-inspired poems. Alfred Binet was just one of many turn-of-the-century psychologists who thought random blots could yield a useful psychological test. But as historian Peter Galison has written, Rorschach’s approach was distinct from all his predecessors’ insofar as he assumed a very different, and modern, self faced with the task of finding meaning in the random stains. Until Rorschach, inkblots had been given primarily to test, or encourage, the autonomous faculty of the imagination. Rorschach rejected the notion of the self as an aggregate of distinct faculties, instead creating examination protocols that assumed a dynamic, integrated self irreducible to distinct components. For this complex subject to speak, the mute inkblots needed to be evacuated of all recognizable cultural references.

In the Rorschach’s heyday, many well-known figures, including Albert Einstein and Franklin D. Roosevelt, submitted to the test, as did the Nazis at the Nuremburg trials and Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961; Ted Bundy and Theodore Kaczynski are two recent test-takers. But outside of the forensic context, the Rorschach no longer holds the preeminent position it once did, having been replaced by more easily administered tests. The same fate has befallen many of the other projective personality tests, a small selection of which is presented here.

The test subject was presented with ten images, selected according to his or her age and sex, and, in a session lasting fifty minutes, was invited to make up as dramatic a story as he or she could for each. The following day the examinee was shown a further ten cards and told to “disregard the commonplace realities and let your imagination have its way, as in a myth, fairy story, or allegory.” One of the last cards was left deliberately blank and the subject was instructed to make up a picture and to describe it in detail.

The subject’s interpretations of each card were thought to reveal aspects of his or her personality and uncover “core complexes.” Morgan and Murray believed a patient’s answers revealed as much as five months’ worth of psychoanalysis. The TAT became one of the most widely administered tests in clinical psychology. It is still in use today.

The test subject is presented with a booklet containing twenty-four cartoon-like pictures, each depicting a frustrating everyday interaction. In each image, two figures are accompanied by speech bubbles. One figure is typically saying something that is likely to frustrate his or her interlocutor; the speech bubble of the listener is left blank, and the examinee is invited to fill in a caption. (The test comes with an additional instruction: “Avoid being humorous.”) Originally, the faces of the two figures were deliberately left void so as to facilitate projection. Later pictures, such as the one depicted here, became increasingly specific when testing for attitudes toward social issues such as racial and ethnic prejudice. The test, which grew out of research intended to prove Freud’s theory of repression, was designed to measure latent hostility and became popular in Europe and the former Soviet Union. It was featured in Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel, A Clockwork Orange (as well as in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 movie of the same name), where it is administered to the protagonist Alex by the sinister “Doctor Vecks.”

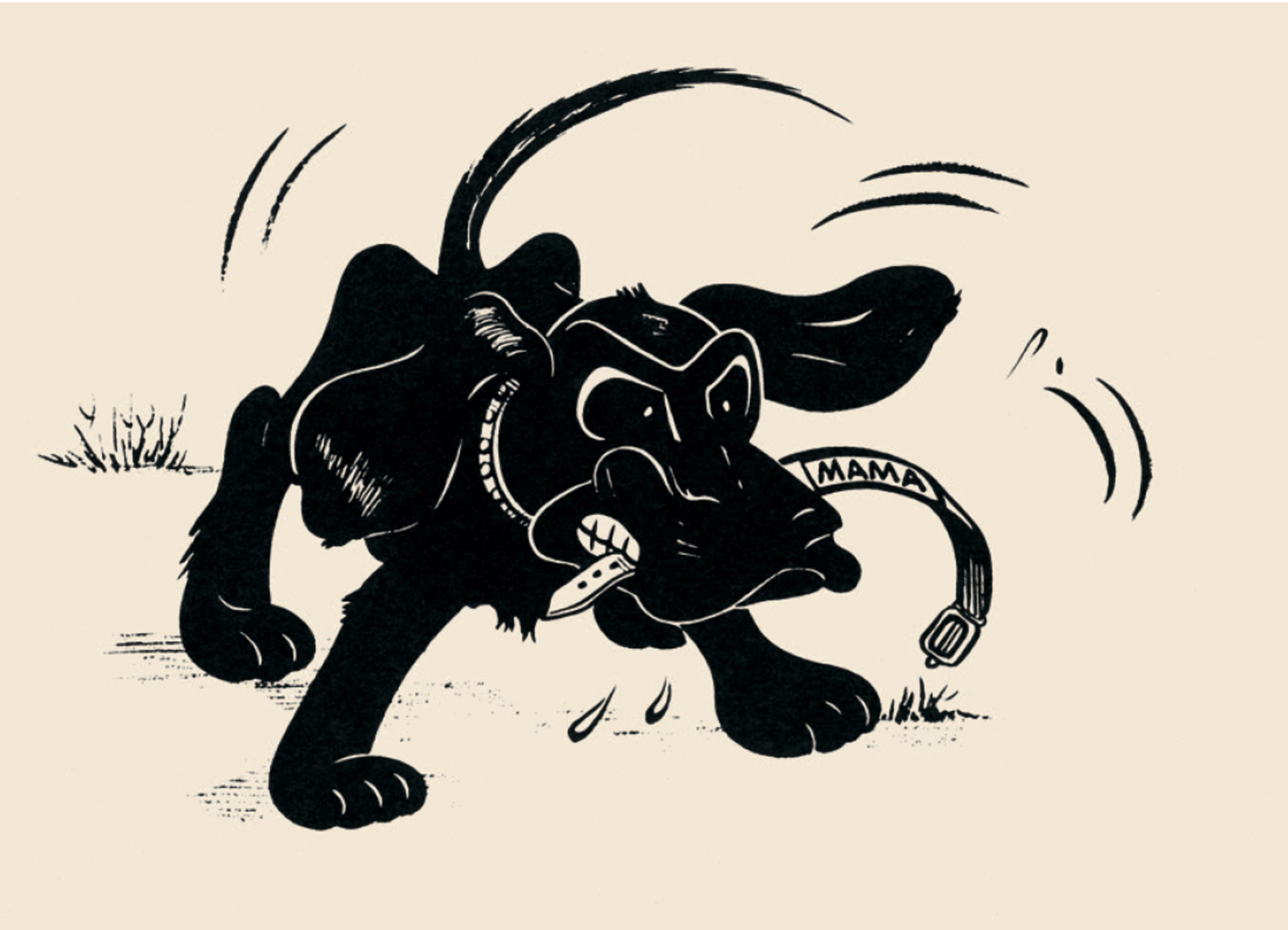

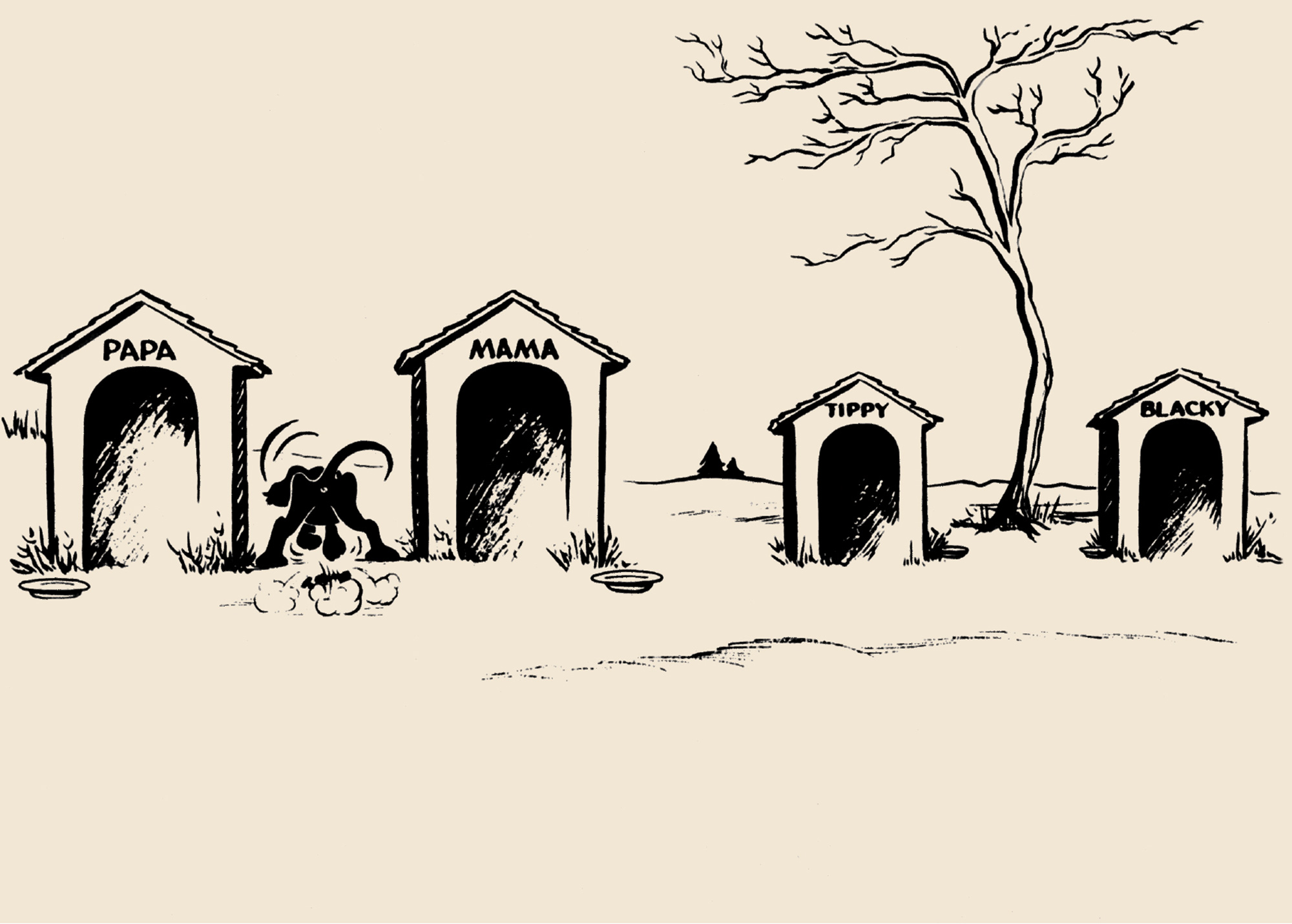

The ambiguity of the black puppy’s activities is intended to help assess the presence of psychological conflicts derived from Freudian theory. Various cartoons were designed around explicitly Freudian crises of personality development, such as Blacky being nursed by his mother (oral eroticism) or Blacky’s sibling about to have his/her tail cut off (castration anxiety). One cartoon pictures Blacky defecating between his parents’ kennels.

The test has fallen out of use.

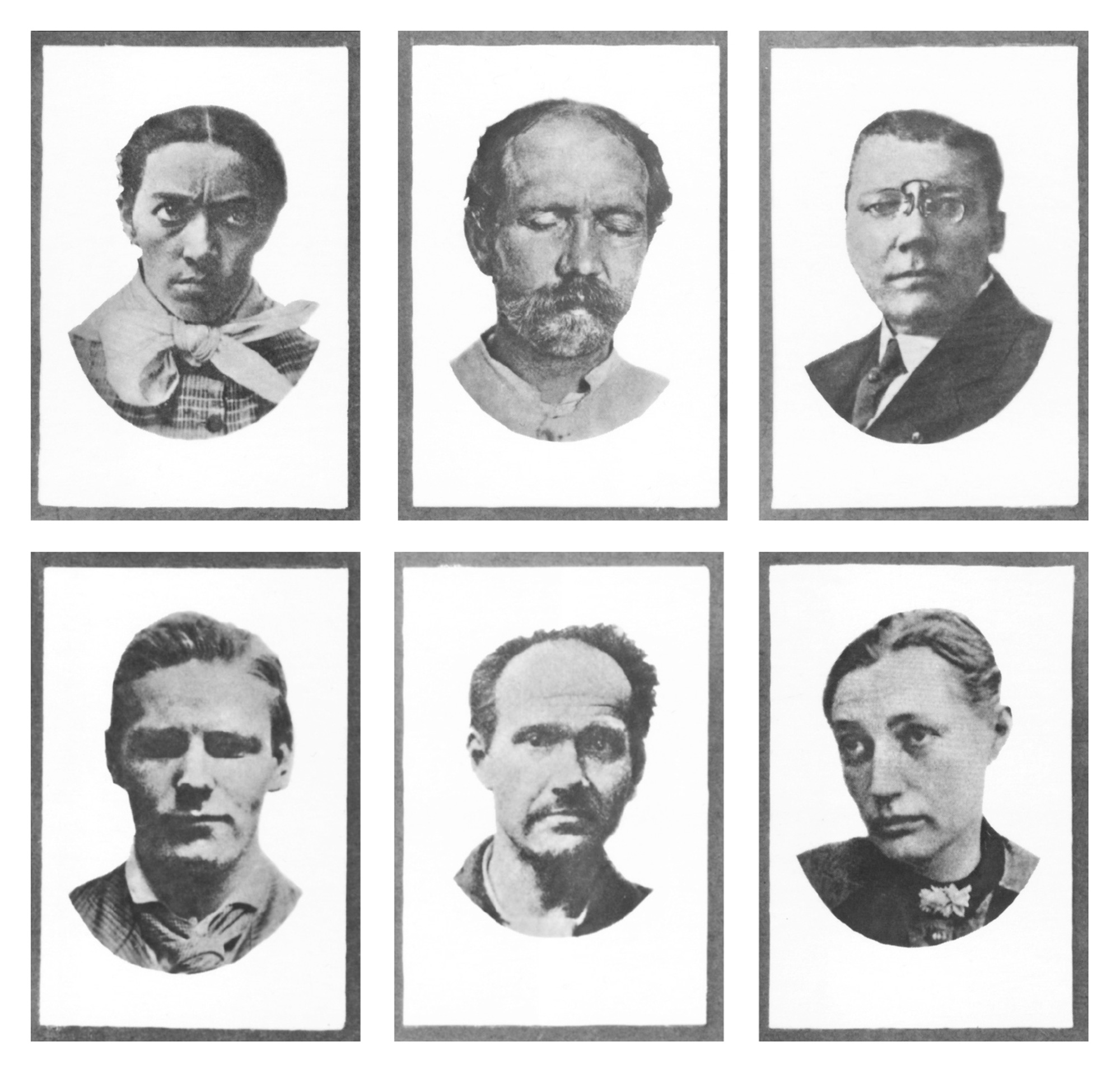

The forty-eight portraits that Szondi selected from a variety of sources were all mental patients whose manifest sickness, Szondi believed, related strongly to a particular “drive factor.” Szondi identified eight such factors, divided among four so-called Vectors: the Sexual Vector; The Paroxysmal Vector, which determines emotional control; The Schizophrenic Vector, which reflects the fluidity of the ego; and the Contact Vector, which indicates the subject’s object relationships. Heavily influenced by psychoanalytic theory, biology, and genetics, Szondi believed that an examinee indicating affinity or distaste for a specific photographs does so “upon the basis of his genic relationship to the person represented by the photograph. This signifies that the person represented by the chosen photograph suffers from a psychiatric disorder (or a characterologic disorder) which also is inherent in the subject’s own familial genealogy.” Humans in Szondian theory were fatalistically determined by their hidden genetic characteristics. The popularity of Szondi’s brand of Schicksanalyse (fate analysis) has declined since the 1970s, although the test has not been completely discarded.

Cabinet wishes to thank Eric Zillmer and Wesley G. Morgan for their generous assistance.

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief of Cabinet.

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.