Measuring Desire

The science of phallometric testing

Tom Waidzunas

In post–World War II Czechoslovakia, the military believed it had a serious problem: male soldiers were escaping service by pretending to be homosexual, falsely obtaining psychiatric “homosexuality certificates” which released them from their duties. In response, a Czech sexologist named Kurt Freund invented a solution: the “phallometric test.” In the interests of ferreting out “fake” homosexuals and distinguishing them from “true” ones, a male subject seeking a certificate would be shown slides of nude men and women while a monitoring device measured the erection level of his penis. Freund and his team would closely examine the soldier’s erection data to determine if he was predominantly homosexual or predominantly heterosexual, and, consequently, whether he should be forced back into the ranks.

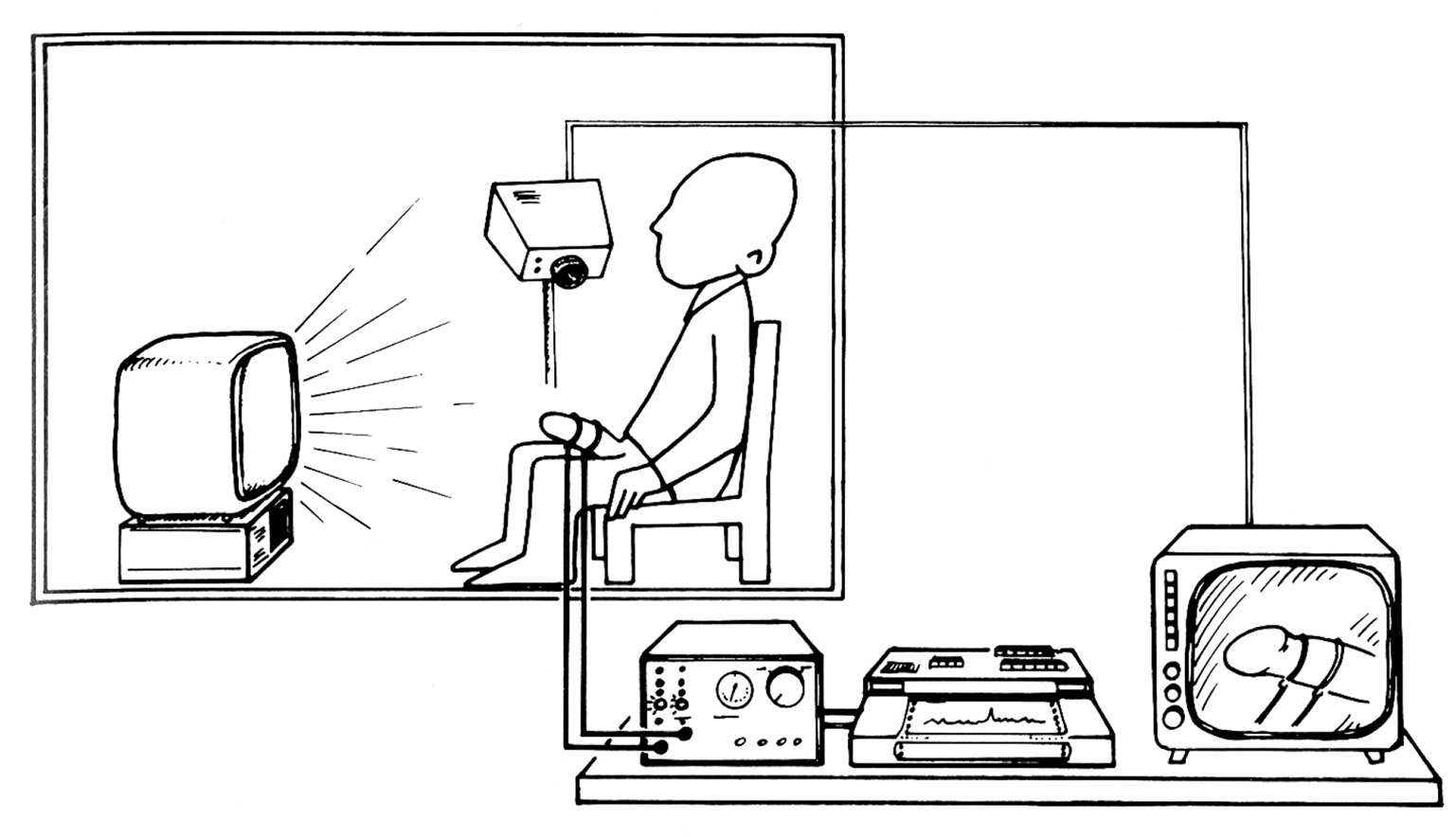

Building on the medical practice of “plethysmography,” whereby physiologists measured the swelling of limbs by sealing them in chambers and measuring displaced air, Freund’s new test was based on the “penile plethysmograph,” the device he had invented to monitor sexual arousal. The original “volumetric air chamber” (VAC) design of the penile plethysmograph included a long, bell-shaped glass tube which was sealed around the base of the penis, while the displacement of air was recorded on an inscription device. A pen recorded the “tracing” of the erection event on a sheet of paper mounted on a rotating drum, typically recording a rise, a sustained erection, and a return to a flaccid state.

But from the beginning, Freund had to deal with the problem of “faking.” It was immediately apparent that some men could withhold erections or even create them on demand, foiling the test’s ability to identify the “true” sexuality within. One technique Freund developed to catch false erections was to scan tracings for what he called “mechanical artifacts,” that is to say, evidence of “pumping.” These artifacts, or jagged lines, in a tracing indicated that a man had faked his erection by flexing muscles attached to his penis. To prevent his subjects from withholding erections, Freund pre-administered testosterone and wine—apparently presuming the penis had a mind of its own when its owner was under the influence of alcohol or a hormonal boost.

Freund soon took his testing apparatus and applied it to other purposes, including the corrective treatment of homosexuality. Aversion therapy, which Freund adopted from behaviorists, presented erotic images along with aversive stimuli such as nausea-inducing drugs or noxious chemicals to purge men of “faulty” sexual desires. Freund’s phallometric test added to this therapeutic regime a new emphasis on precise measurement. To Freund’s surprise, when he applied his diagnostic method, he found that he could diminish same-sex attraction but could not induce heterosexuality. Consequently convinced that sexual orientation could not be changed, Freund became an influential advocate for the legal changes that ultimately led to the decriminalization of homosexuality in Czechoslovakia in 1961.

While many sexologists liked the concept of phallometric testing, the VAC device proved cumbersome in the laboratory. A sleeker design called the “mercury-in-rubber strain gauge,” or the “circumferential transducer,” was invented by British sexologist John Bancroft in 1966, and quickly became the most popular technique among researchers for its ease of use: all the subject was required to do was place an expandable ring onto the shaft of his penis. But while the new device was simpler, Freund and another VAC advocate, Nathaniel McConaghy, argued that the circumferential transducer was inferior because of the dynamics of erection. Freund and McConaghy tested men wearing both devices simultaneously and found that, at low levels of arousal, the penis expands in length before it expands in girth. In fact, penile girth tends to decrease slightly before it expands during the early stages of erection. This initial expansion is detected by a volumetric air chamber, but not by a circumferential transducer. Nevertheless, the simpler method prevailed.

Today, the strain-gauge phallometric test has found its way into many other applications, including testing for impotence within urology and predicting recidivism among sex offenders (the erotic stimuli used in the latter instance are audio vignettes when slides or videos would take the form of illegal child pornography or offensive violent imagery). Despite these continued applications, the persistence of the problem of faking and the frequency of non-responses in phallometric tests both continue to raise questions about the validity of such procedures for measuring male sexual arousal and the meaning of such measurements.

Tom Waidzunas is a doctoral candidate at University of California San Diego studying science studies and sociology. His dissertation is a social history of epistemic struggles over sexual reorientation therapies for homosexuality that involve the characteristics, ethics, and boundaries of science. For more information see sociology.ucsd.edu/~twaidzun [link defunct—Eds.].