Ingestion / Planet in a Bottle

Extended life through calorie restriction

Christopher Turner

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

At 8:15 am on 26 September 1991, eight “bionauts,” as they called themselves, wearing identical red Star Trek–like jumpsuits (made for them by Marilyn Monroe’s former dressmaker) waved to the assembled crowd and climbed through an airlock door in the Arizona desert. They shut it behind them and opened another that led into a series of hermetically sealed greenhouses in which they would live for the next two years. The three-acre complex of interconnected glass Mesoamerican pyramids, geodesic domes, and vaulted structures contained a tropical rain forest, a grassland savannah, a mangrove wetland, a farm, and a salt-water ocean with a wave machine and gravelly beach. This was Biosphere 2—the first biosphere being Earth—a $150 million experiment designed to see if, in a climate of nuclear and ecological fear, the colonization of space might be possible. The project was described in the press as a “planet in a bottle,” “Eden revisited,” and “Greenhouse Ark.”

Before entering, the Biosphere’s pioneer inhabitants had enjoyed a final, hearty breakfast consisting of ham, eggs, and buttered bread, but from here on, they would be self-sufficient—everything they ate would be grown, processed, and prepared in their airtight bubble. A few years before designing the Biosphere, architect Phil Hawes had proposed a space city 110 feet in diameter, a flying doughnut that would spin to create its own gravity and in which miniature animals could be kept and plants cultivated, along with a store of cryogenically frozen seed for the propagation of twenty thousand other species. The space frame of the Biosphere, a terrestrial version of such a sci-fi fantasy, had been built by an engineer who had worked with Buckminster Fuller, author of Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, which compared the planet to a spaceship flying through the universe with finite resources that could never be resupplied. The Biosphere was intended as a similar symbol of our ecological plight.

The project caught the national imagination. Discover, the popular science magazine, declared the mission “the most exciting venture to be undertaken in the US since President Kennedy launched us towards the moon.” Tourists came by the busload to peer through the glass at the bionauts, trapped in their vivarium like laboratory rats (the project was an acknowledged precursor to the Big Brother reality-TV show). Over the first six months, 159,000 people visited, including William S. Burroughs and Timothy Leary.

Life inside the glass city was colored by its inventors’ countercultural idealism. They had all met on the Synergia Ranch, a commune they founded near Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the late 1960s and ran according to Wilhelm Reich’s idea of “work democracy”; they practiced improvisational theatre and made a fortune building developments of adobe condos, which helped pay for the Biosphere (the commune is described in Laurence Veysey’s 1971 ethnography, The Communal Experience: Anarchist and Mystical Communities in Twentieth-Century America). The Biosphere’s half-acre arable plot had been cultivated for three months in preparation for the crew’s arrival to what was supposed to be a high-tech Eden. However, the members of the chosen team lacked experience as farmers and, despite reading how-to manuals with titles such as How to Grow More Vegetables than You Ever Thought Possible on Less Land than You Can Imagine, yields were disappointing and they began to starve.

The bionauts had to perform hard physical labor to produce their food, but there was only enough for them to consume a measly 1750 calories a day, and they found it difficult to sustain such active lives. On a diet of beans, porridge, beets, carrots, and sweet potatoes, their weight plummeted and their skin began to go orange as a result of the excess beta-carotene in their diet. “It was very stressful, especially with a crew like that,” recalled Sally Silverstone, the Agriculture and Food Systems Manager, “essentially white middle-class, upper-middle-class Western individuals who had never been short of food in their whole life—it was a tremendous shock.”

Silverstone would weigh out the day’s allotment of fresh food for whoever’s turn it was to cook, entering into a computer database the amount of nutrients to check that the crew was keeping above the recommended intake levels of calories, proteins, and fats. At first the meals were served buffet style but, as the crew got hungrier, the cooks scrupulously divided their offerings into equal portions. Leaving every meal still hungry, all the bionauts could think about was food, and their memoirs of the two-year project are full of references to their recurring dreams of McDonald’s hamburgers, lobster, sushi, Snickers-bar cheesecake, lox and bagels, croissants, and whiskey. They bartered most of their possessions, but food was too precious to trade. They became sluggish and irritable through lack of it, and were driven by hunger to acts of sabotage. Bananas were stolen from the basement storeroom; the freezer had to be locked.

The medic who presided over the team’s health was Dr. Roy Walford, a professor of pathology at UCLA Medical School who had served in the Korean War and, at sixty-nine, was the oldest member of the crew. He was a gerontologist and specialist in life extension who, in studies with mice, thought that he’d successfully shown that one could live longer by eating less; his skinny mice outlived his fat ones by as much as forty percent. In his books Maximum Life Span (1983) and The 120-Year Diet (1986), Walford promised that “calorie restriction with optimal nutrition, which I call the ‘CRON-diet,’ will retard your rate of aging, extend lifespan (up to perhaps 150 to 160 years, depending on when you start and how thoroughly you hold to it), and markedly decrease susceptibility to most major diseases.”

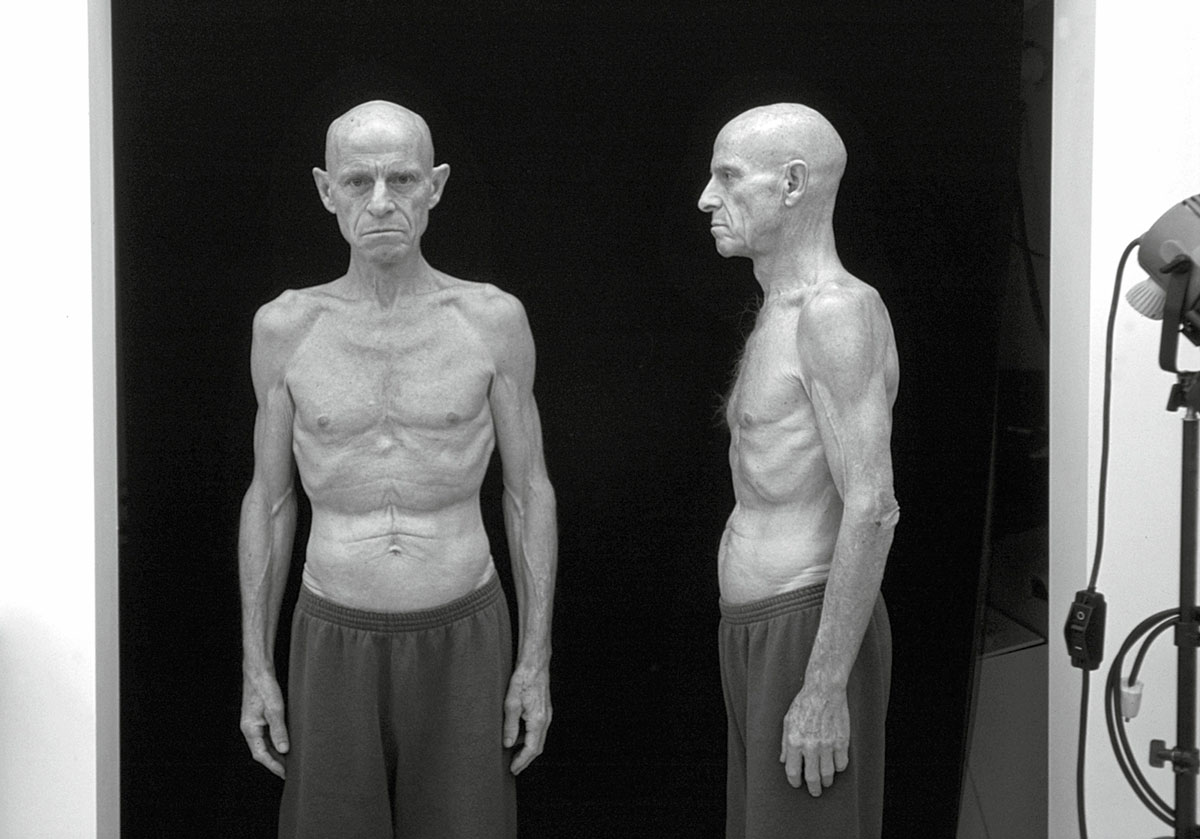

The disappointing crop yields in the Biosphere allowed Walford to experiment with his “healthy starvation diet” on humans in unprecedented laboratory conditions. While his subjects pleaded with mission control for more supplies, Walford—who had been on the CRON-diet for years—maintained that their daily calorie intake was sufficient. “I think if there had been any other nutritionist or physician, they would have freaked out and said, ‘We’re starving,’” Walford said, “but I knew we were actually on a program of health enhancement.” Every two weeks he would give them all a full medical checkup. He discovered that their blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol counts did indeed drop to healthier levels—which he presumed would retard aging and extend maximal lifespan as it seemed to in mice—though an unanticipated side effect of this was that their blood was awash with the toxins that had been stored in their rapidly dissolving body fat.

In their 1993 book Life Under Glass: The Inside Story of Biosphere 2, crew members Abigail Alling and Mark Nelson note: “Each biospherian responded differently to the diet. Initially, over the first six months or so, we lost between eighteen and fifty-eight pounds each. ... Roy continued to assure us not to worry when we commented on our baggy pants and loose shirts because our overall health was actually improved by the combination of our diet and the superb freshness and quality of the organically grown food.” They acknowledged that their natural diet was incredibly healthy: “The only problem was that there never seemed to be enough of it.” Every month Walford took a Polaroid photo of each member that recorded their dramatic physiological changes—men lost eighteen percent of their body weight, women ten percent, mostly within the first six months.

During her two years inside, Silverstone wrote a cookbook with the fantastic title, Eating In: From the Field to the Kitchen in Biosphere 2, which contains forty-eight recipes from the biospherian diet, along with the story of how the crew planted, grew, processed, and prepared the food on their half-acre farm. In the book, the team are photographed a year into the mission, standing behind a table loaded with food, but they all look gaunt and bony. By this time, the team had splintered into two opposing factions that barely spoke to each other, but they still ate together (a favorite dinner spot was the balcony overlooking the Intensive Agriculture Biome, from which you could see the sun setting over the Catalina mountains and which they dubbed the Café Visionaire). They stockpiled their supplies for such feasts, sacrificing livestock and saving milk, eggs, figs, and papayas, and lubricating the meals with homebrew or punch spiked with alcohol from Walford’s medical supplies. The menu for their first Thanksgiving feast was:

Baked chicken with water chestnut stuffing

Sautéed ginger beets

Baked sweet potatoes

Stuffed chili peppers sautéed with goat cheese

Tossed salad with a lemon-yogurt dressing

Orange banana bread

Tibetan rice beer (chung)

Sweet potato pie topped with yogurt

Cheesecake

Coffee with steamed goat’s milk

The rest of the time they were so famished they chewed on peanut shells, coffee grounds, and banana skins. Fennel leaves became known as “biospherian chewing gum.”

When the crew emerged from the experiment after two years, the project was judged by the media to be a failure. Early in the second year, carbon dioxide levels had risen so high (twelve times that of the outside) that the crew were growing faint and Walford asked for more oxygen to be pumped into the structure on two occasions. The Biosphere had proved not to be a self-sufficient, autonomous world as it would need to be if it were to become a base station on another planet. In 1999, by which time the Biosphere had been taken over by Columbia University as a research center into the effects of climate change,Time magazine judged it one of the hundred worst ideas of the twentieth century. But Walford’s experiments with diet, reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in December 1992, were judged a success. The bionauts not only showed dramatic weight loss (stabilizing at an average of fourteen percent overall), but also lower blood pressure and cholesterol, more efficient metabolisms, and enhanced immune systems.

The year after his release, Walford began the Calorie Restriction Society, which now has seven thousand members (it is estimated that one hundred thousand practice the diet worldwide). The CRONIES, as Walford’s devotees refer to themselves, measure and weigh out everything they consume using electronic scales, the idea being that each calorie you consume should contain as many nutrients as possible (you can download Cron-O-Meter software free on the internet to help plan such a diet). The CRONIES live at the border of self-starvation, in the hope of delayed gratification; like their mentor, they live in their own biosphere, a self-absorbed bubble of discipline and resolve, and maintain the science-fiction dream of an age when we will all be able to live forever. Calorie restriction failed to dramatically increase Walford’s lifespan, however: he died in 2004 of Lou Gehrig’s disease, aged seventy-nine.

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came to America, will be published in June 2011 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US and HarperCollins in the UK.