Drawing the Foul

Simulation and dissimulation on the soccer pitch

Luke Healey

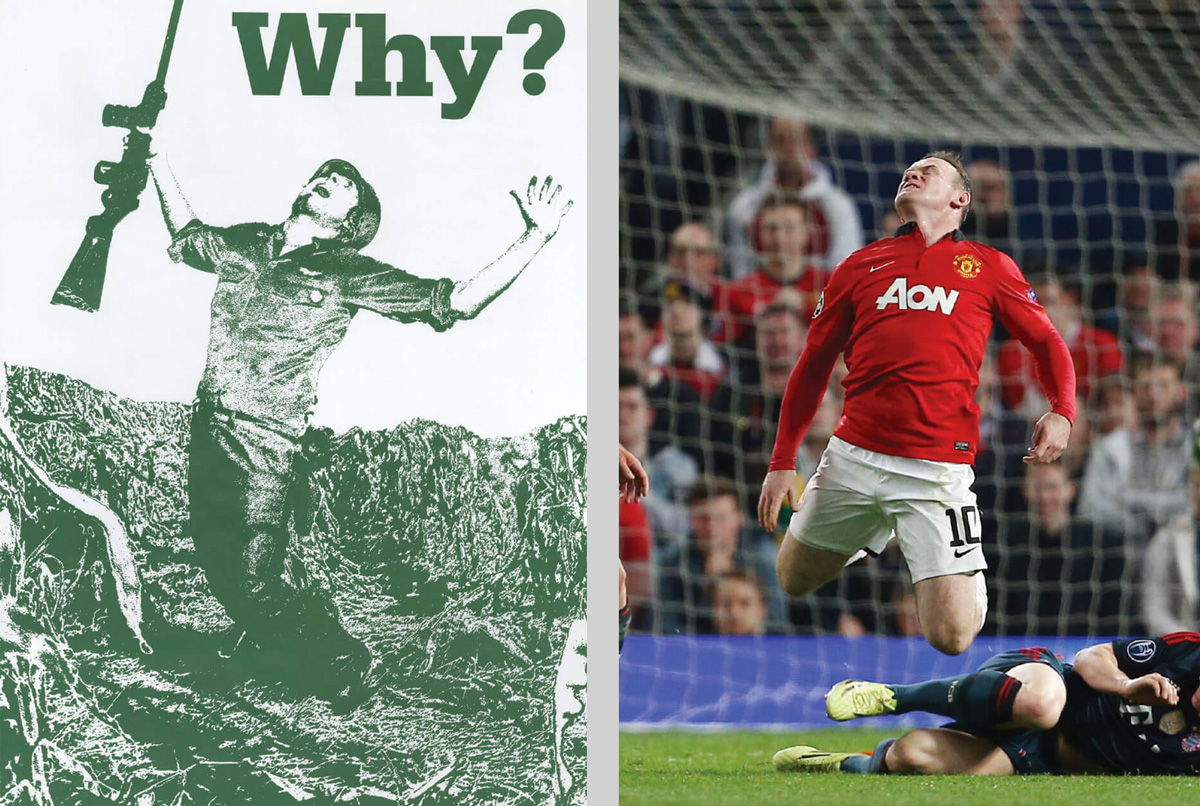

On 2 April 2014, the German soccer magazine 11Freunde tweeted one of its occasional “Bei der Geburt getrennt” (separated at birth) vignettes, which typically attempt to milk humor from the resemblance between footballers and other public figures from culturally disparate fields. The diptych concerned the European Champions League quarterfinal match between Manchester United and Bayern Munich played the previous evening. Late in the game, the referee had made a controversial decision to send off Bayern’s Bastian Schweinsteiger for a sliding tackle on United’s Wayne Rooney—his second bookable offence. Rooney was widely judged to have made Schweinsteiger’s tackle look more brutal than it really was, and thus stood accused of “simulation,” an offense prohibited following a ruling of the International Football Association Board in March 1999. In that year, the twelfth of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association’s seventeen Laws of the Game was changed to include a clause stating, “Any simulating action anywhere on the field, which is intended to deceive the referee, must be sanctioned as unsporting behaviour.”[1] Since then, a player guilty of simulation—or “diving,” as it is colloquially known—must be shown a yellow card.

The wags behind 11Freunde’s social media rendered their own accusation of simulation by suggesting kinship between Rooney and a dying soldier depicted in an antiwar poster. These two images do indeed contain a common gesture: like the soldier, Rooney’s arms are extended behind his body, his knees buckled, and his face arranged in a grimace. The spirit of this gag is clear: Rooney had no right to assume the posture of a dying brother-in-arms, and was a pompous fraud for having done so. For anyone weaned on the English Premier League, which supplanted the old Football League Division One in 1992, there is another irony. When increased television revenues made it easier for Premier League clubs to recruit talented foreign players—aided in turn by the so-called Bosman Ruling of 1995, which made it illegal for leagues in the European Union to place restrictions on the number of EU citizens their teams were permitted to sign—it was German footballers who became the first foreign group to be saddled with a blanket reputation as divers by the English press. The caption to a photograph of Jürgen Kohler, published in the Times in June 1994, described the defender as “executing a nine-point dive in the accepted German manner.”[2] When striker Jürgen Klinsmann (latterly coach of the US men’s national soccer team) joined Tottenham Hotspur in 1994, his deceitful reputation was so entrenched that he acknowledged it in goal celebrations in which he dived theatrically onto his stomach and slid along the turf. (The ever-inflammatory Luis Suarez did likewise in 2012, in response to accusations from Everton manager David Moyes.)

English footballers, by contrast, have long been seen by their fans as untainted by the duplicitousness made manifest in diving. The notion of diving as a foreign contagion was notoriously espoused by Manchester United manager Sir Alex Ferguson and England national captain John Terry, among others, the latter opining in 2009, “I can speak about the England lads and I think it is something we don’t do. … I think we’re too honest, sometimes even in the Premier League you see the English lads get a bit of contact and stay on their feet and try and score from the chance they have been given.”[3] Diving is antithetical to the self-ascribed characteristics of the English game—“strength, power, energy, fortitude, loyalty, courage,” as enumerated by David Winner in his book Those Feet: A Sensual History of English Football.[4] These salt-of-the-earth virtues are widely supposed to be dying out in English soccer as it moves further and further away from its traditional social base, as the leagues fill up with flashy migrants, and working-class communities find themselves excluded from elite-level games by ticket price hikes. Given this, English fans find it especially difficult to accept diving from the decidedly less-than-cosmopolitan Rooney, a rumbustious and powerful forward who has been trading for some years off the reputation he established, during his early seasons at Everton and Manchester United, as a prototype of virtuous English football.

The English idea that diving is a foreign novelty introduced by the international reach of the Premier League is contradicted by earlier commentary on the game. Perhaps the moral panic over the rise of cynicism in soccer can be traced back to the day after the sport’s initial codification in December 1863. But certainly by 1975—long before the arrival of foreign players—a Daily Express article could record the Huddersfield player Brian O’Neil’s “cheerful” admission “that he had dived to win a penalty ... in other words that he had faked and cheated,” warning that with this confession, soccer had been “sent hurtling faster still towards complete moral decay.”[5] The language here is practically indistinguishable from commentaries on diving from the 1990s and 2000s: Mick Dennis’s article from a 2011 issue of the Daily Express, for example, presents a dive by Bulgarian striker Dimitar Berbatov as evidence that “chicanery has become commonplace” and an illustration of “how debased football has become.”[6] Historical continuities notwithstanding, newspaper archives clearly demonstrate that with English soccer settling uneasily into the cosmopolitan, highly mediatized, commodified, and embourgeoisified paradigm introduced by the Premier League, the 1990s marked the moment when diving became the national game’s Big Bad.

This context alone does not, of course, fully explain the increase in commentaries on diving from the early 1990s on. For instance, television coverage of English soccer increased rapidly during this time, accompanied by improvements in instant replay technology, and both made diving incidents easier to spot and analyze. But regardless of the real causes, it is undeniable that over the course of the decade, commentaries on diving became a rhetorical device through which certain perceptions about the pitfalls of increased internationalization could be represented. Often, and perhaps unsurprisingly, this rhetoric uses diving as a means of associating foreignness with effeminacy. Though the occasional overseas player has been known to flop to the floor “like a sack of potatoes,”[7] it is more characteristic to find them swooning like the hysterical transvestite Emily from the BBC sketch show Little Britain, or “going down like Monica Lewinsky in the Oval Office”—to offer just two images from the columns of tabloid journalist Des Kelly.[8] When they don’t employ direct homo- or transphobia, commentators may choose to characterize divers as merely louche, luxurious, and effete: this impression is summoned, for example, by Kevin Moseley’s image of Klinsmann taking “a quick dive into the Mediterranean” from Tottenham chairman Alan Sugar’s yacht in Monte Carlo, or by Harry Harris’s reference to the “dying swan impression” of Chelsea’s Ivorian striker Didier Drogba.[9] The idea of an English soccer player engaging in transvestism, going down on a world leader, schmoozing in Monaco, or lacing up a pair of ballet pumps is, we are supposed to believe, ludicrous and beyond the pale.

• • •

There can be little room for error in the 11Freunde tweet, however: Rooney’s posture could hardly be more redolent of the characteristic iconography of diving. The pose—which calls to mind nothing so much as the arc de cercle that nineteenth-century French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot noted in outbursts of hysteria in patients at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris—is a go-to resource for newspaper editors seeking to stir up scandal around the issue of diving. It is also increasingly found in representations like the piñata made in the likeness of certified diver Arjen Robben, created by Mexican fans after their 2014 World Cup defeat to the Netherlands. One of the most widespread images of this type among amateur writers publishing online is a professional photograph of Drogba taken during the Ivory Coast’s 2006 World Cup match against Argentina. In it, the circular effect of the player’s bent limbs shares something of the gestural elegance of the platform diver, demonstrating what Steven Connor, in reference to those athletes, has described as a “closing of the curve on itself, in a defiance of the order of the direct and the perpendicular.”[10]

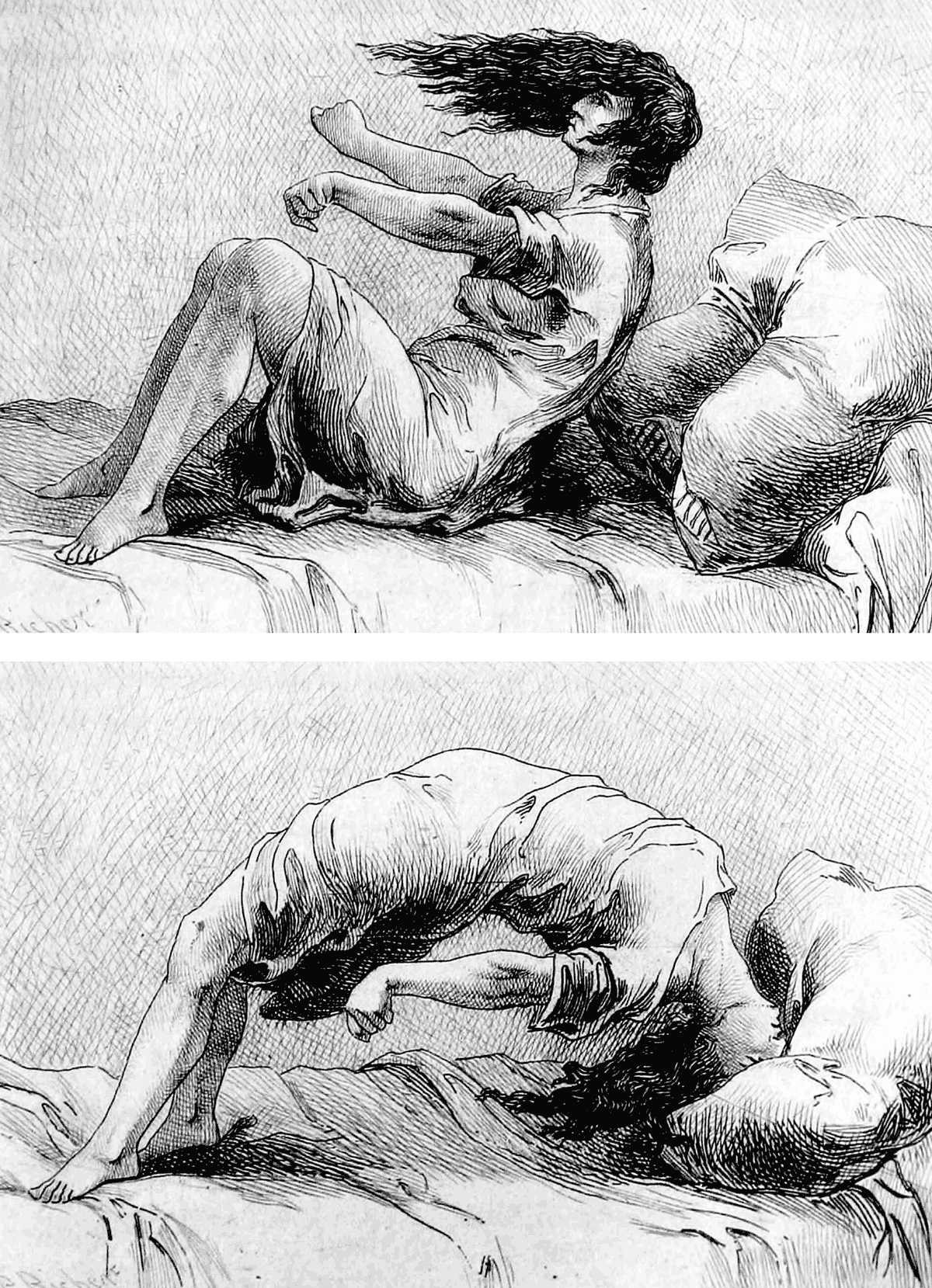

The observations that can be made of images like the ones of Drogba and Rooney—or, to add a third, of Neal Simpson’s photograph of Leeds United’s Harry Kewell taken during the 1999–2000 Premier League season—tend toward the paradoxical. The players in question appear to have lost all control, their bodies tormented by the demonic energies of a hysterical episode or by a fatal blow to the back. At the same time, their poses are articulated with a certain grace and artistry that invites sustained contemplation of such images. Taking the comparison with hysteric patients a step further, one might note the tendency toward “simulation” that was known to occur under Charcot’s watch. Georges Didi-Huberman, for instance, argues that in Charcot’s wards at the Salpêtrière, “every hysteric had to make a regular show of her orthodox ‘hysterical nature’” in order “to avoid being transferred to the severe ‘division’ [for] … incurable ‘alienated women.’”[11] Hysterics, by this account, retained some mastery over their violent displays, pressing them into the most stereotypical forms when doing so enabled them to gain some small amelioration of their miseries. Footballers may be worlds apart from hysteric patients in most respects, but their simulations are similarly calculated to eke out advantages, which are sometimes enough to change the game: witness Fred’s dive in the box to win the penalty that gave Brazil the lead over Croatia in the opening game of the 2014 World Cup.

• • •

In Paul H. Morris and David Lewis’s behavioral psychology study “Tackling Diving: The Perception of Deceptive Intentions in Association Football (Soccer),” the researchers present a taxonomy of simulation in soccer. It has four categories, all of which offer referees clear guidance in distinguishing simulation from genuine foul play. The absence of “temporal contiguity,” “ballistic continuity,” or “contact consistency” in relation to the tackle that prompted the fall in question are all indications that the player has in fact dived.[12] In addition, Morris and Lewis identify a fourth category, which they call the “archer’s bow,” a behavior “unique to deception.”[13] In “its most complete form,” the authors state, “the tackled player resembles a drawn bow: the chest is thrust out; the head is back; the arms are fully raised and pointing upwards and back; the legs are raised off the ground and bent at the knee.”[14] Morris and Lewis’s identification of this posture advances the notion that diving has its own proper form of expression, arising independently of the actions integral to the rest of the game. The images of Drogba and Kewell show this form of expression in its most “perfected” state.

Morris and Lewis confess that “the origin of the set of behaviours we name the ‘archer’s bow’ is to a degree puzzling,” before noting that the most straightforward motivation is communicability: “the behaviour is clearly noticeable.”[15] Remarking that the position adopted by players performing the “archer’s bow” is contrary to the momentum that challenges would ordinarily create in the tackled player, and furthermore offers little by way of self-protection, the researchers surmise that “the ‘archer’s bow’ is used by the player to convey the extreme nature of the collision; it is so intense that all the normal self-protection mechanisms involved with preparing for the fall cannot be utilized.”[16] In reaching for the apex of expressive representation, the “archer’s bow” thus reveals its own essential falsity. Morris and Lewis subsequently compare the ur-image of the “archer’s bow” to Robert Capa’s famous 1936 photograph of a dying Spanish Republican soldier, a juxtaposition intended to connect their own material to a work that belongs to a visual tradition of hyperbolic violence and heroic suffering. (I will leave aside the controversy over the veracity of this photograph, which has at least since 1975 been suspected of having been staged.) This, of course, is the same gesture made by the 11Freunde diptych. For those interested in iconography, these pairings propose diving as a kind of bodily autopoiesis, a moment stolen from the normal creative performance of “the beautiful game” in which the player strives to embody a resonant posture, to become more artwork than artist.

• • •

As much as diving represents a problem of sporting ethics, the phenomenon cannot be fully understood without a consideration of aesthetics. Diving is profoundly tied to questions about the status of images and of image making. The idea that star players produce picture-worthy moments of sublime skill while humbling their opposition is as old as the game itself. Today, working symbiotically with a photographic apparatus that records their every movement, soccer players can attempt the “archer’s bow” as a means of turning themselves into pictures, visual representations of violence and vulnerability calculated to affect and influence the relevant audience, namely the referee and his or her assistants.

What a gift this is to an art historian! Though not their direct intention, diving soccer players are a boon to the visual analyst who wants to take sports photography seriously, who seeks deep lineages for its iconographies and pathos formulae. The talented diver calls to mind Laocoön, or Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa, because there are few stronger examples of the representation of bodily extremes. The flip side of this expert performance is opprobrium from the world of soccer itself. W. J. T. Mitchell has written of the “default feminization of the picture,” and his words resonate with an intriguingly iconophobic article from the September 1981 edition of FIFA’s in-house publication, FIFA News.[17] Written by René Courte, then public relations and press officer for the federation, the piece describes the resolutions of a meeting of FIFA’s Technical Committee, whose members, Courte recounts,

expressed their concern about the excessive demonstrative attitude of some players and teams when a goal is scored. For several years various National Associations have attempted to subdue the un-manly behaviour of some football players who embrace, kiss and hug each other in an over-emotional fashion after scoring a goal.[18]

The identification of an “excessive demonstrative attitude” in goal celebrations suggests a suspicion that visuality is a subversive force, one that FIFA feels compelled to police and regulate. Visual historian and soccer scholar Horst Bredekamp notes that the attempted implementation of Courte’s ideas was at the time badly received, arguing that virtually no “announcement of recent times has met with such unanimous refusal as this ban on body contact.”[19] The proscription was never ratified, yet the 1981 Technical Committee’s concern over visual exuberance has gradually found expression in rules such as the one that punishes players who remove their shirts to celebrate goals, added to FIFA’s Laws of the Game in 2004. As contemporary tabloid rhetoric about simulation shows, similar anxieties over excessive demonstrativeness, and associated fears about feminization, also frame commentaries on diving.

Courte’s generation of regulators did not have to contend with the vast image economy that soccer spawned in the following decades. Commentators like Des Kelly appear as residual believers in the ethos outlined in the 1981 document, writing late into the profoundly mediatized 1990s. In a 1999 column for the Mirror, a British tabloid, Kelly discusses the French winger David Ginola, then playing for Tottenham. Ginola’s long hair and silky skills already placed him under a certain degree of suspicion in the muscular, no-nonsense world of English soccer. That Ginola was also known to dive transformed this suspicion into a full-blown crisis of masculinity. Kelly criticizes the player for possessing the “morals of a pop tart,” and finds a way to intimately tie his Frenchness to his suspect masculinity by referring to him, in an appropriation of the name of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s beloved character, as a “Little Ponce.”[20] Kelly has no problems admitting that Ginola is a fine footballer; what is taboo here is the player’s awareness that he is one of the best, a self-consciousness that manifests itself distastefully whenever he dives:

Ginola is revered by the Spurs fans, not because he has mastered the careful flick of the locks, the Gallic shrug, or the winning smile for the camera. He is lauded at the club because he is a footballer who has the ability to make the White Hart Lane admission charge seem worthwhile with one scintillating run, a jaw-dropping turn or a searing shot.

Sadly, he does not seem to understand that one pitiful somersault with pike over an imaginary leg destroys that magic.[21]

For Kelly, Ginola rewards those who invest in the spectacle of his performances when he demonstrates his skills. His ability to turn his absorption in the game into beautiful play leads in turn to an absorbing spectacle for the gathered crowd. When Ginola reaches beyond on-field absorption, however, and dives—and Kelly ties this expressly to the player’s exotic sense of vanity—he pulls back the curtain to “destroy the magic.” This argument calls to mind the anti-theatrical ideas put forward by Denis Diderot in his Paradoxe sur le comédien, with particular gender conceptions thrown in.[22] To wit, when Ginola’s performance dissolves into a form of demonstrativity that implicitly acknowledges the presence of an audience, he debases the game and feminizes himself. However, Ginola’s feminization is not just self-directed: if, following Mitchell, we consider the picture to possess a value coded feminine by default, then Ginola’s dives dismantle football’s magic, the magic that justifies an admission charge, by portraying in unacceptable clarity the player’s exhibition value. Ginola’s critical act of autopoiesis, his sudden shift from artist to artwork, reflects the audience’s gaze back on itself, bringing to light a massive, non-normative circuitry of men-watching-other-men, found anywhere sport is followed.

• • •

Soccer’s reputation as “the beautiful game” means that its events and protagonists are often described in terms that borrow from high aesthetic discourse. Doing so, however, can sometimes feel like a colonization, a means of forcing a vibrant and historically proletarian entertainment into a framework of genteel discourse. In diving, soccer players insert themselves into this process of translation as they claim for their own ends forms of representation that lie outside of the relatively narrow range of available on-field actions.

In so doing, they reach out to the visual analyst on their own terms, at great risk to their professional credibility. For these beautiful, unacceptably expressive images, I thank them.

- Fédération Internationale de Football Association, Laws of the Game 1999 (Zurich: Fédération Internationale de Football Association, 1999), p. 27.

- Simon Barnes, “Bizarre Moments Attract Coveted Awards,” The Times, 29 June 1994.

- Mikey Stafford, “England v Slovenia: England Are Too Honest to Dive, Says Terry: Playing Fair Can Go Against Us, Says Capello’s Captain: ‘England Lads Get Contact But Try to Stay on Feet,’” The Guardian, 5 September 2009.

- David Winner, Those Feet: A Sensual History of English Football (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), p. 7.

- Alan Thompson, “Now Hit Them Hard,” Daily Express, 3 November 1975.

- Mick Dennis, “Honest Theo Shouldn’t Be the Fall Guy,” Daily Express, 11 January 2011.

- Richard Lewis, “Flop Yuran Is Warned: Don’t Blow It by Diving,” Daily Express, 15 January 1996.

- Des Kelly, “Football’s Prize Hams Make My Stomach Turn,” Daily Mail, 29 December 2004; Des Kelly, “The Dive Artist Formerly Known as Prince...,” The Mirror, 22 January 1999.

- Kevin Moseley, “The Diver with a Soft Centre!,” Daily Express, 30 July 1994; Harry Harris, “Fall-Guys Will Need Our Help,” Daily Express, 25 March 2006.

- Steven Connor, A Philosophy of Sport (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), p. 115.

- Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, trans. Alisa Hartz (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), p. 170.

- Paul H. Morris & David Lewis, “Tackling Diving: The Perception of Deceptive Intentions in Association Football (Soccer),” The Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, vol. 34, no. 1 (March 2010), p. 8.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 11.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), p. 44.

- René Courte, “Editorial,” FIFA News, no. 220 (September 1981), p. 461.

- Horst Bredekamp, Bilder bewegen: Von der kunstkammer zum endspiel aufsätze und reden (Berlin: Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, 2007), p. 159. My translation.

- Des Kelly, “The Dive Artist Formerly Known as Prince.”

- Ibid.

- See Michael Fried, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980).

Luke Healey is a writer and a PhD candidate in the department of Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Manchester. His doctoral research concerns the relationship between football and visual culture at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first.