Astronymy

The philosopher’s stone

Justin E. H. Smith

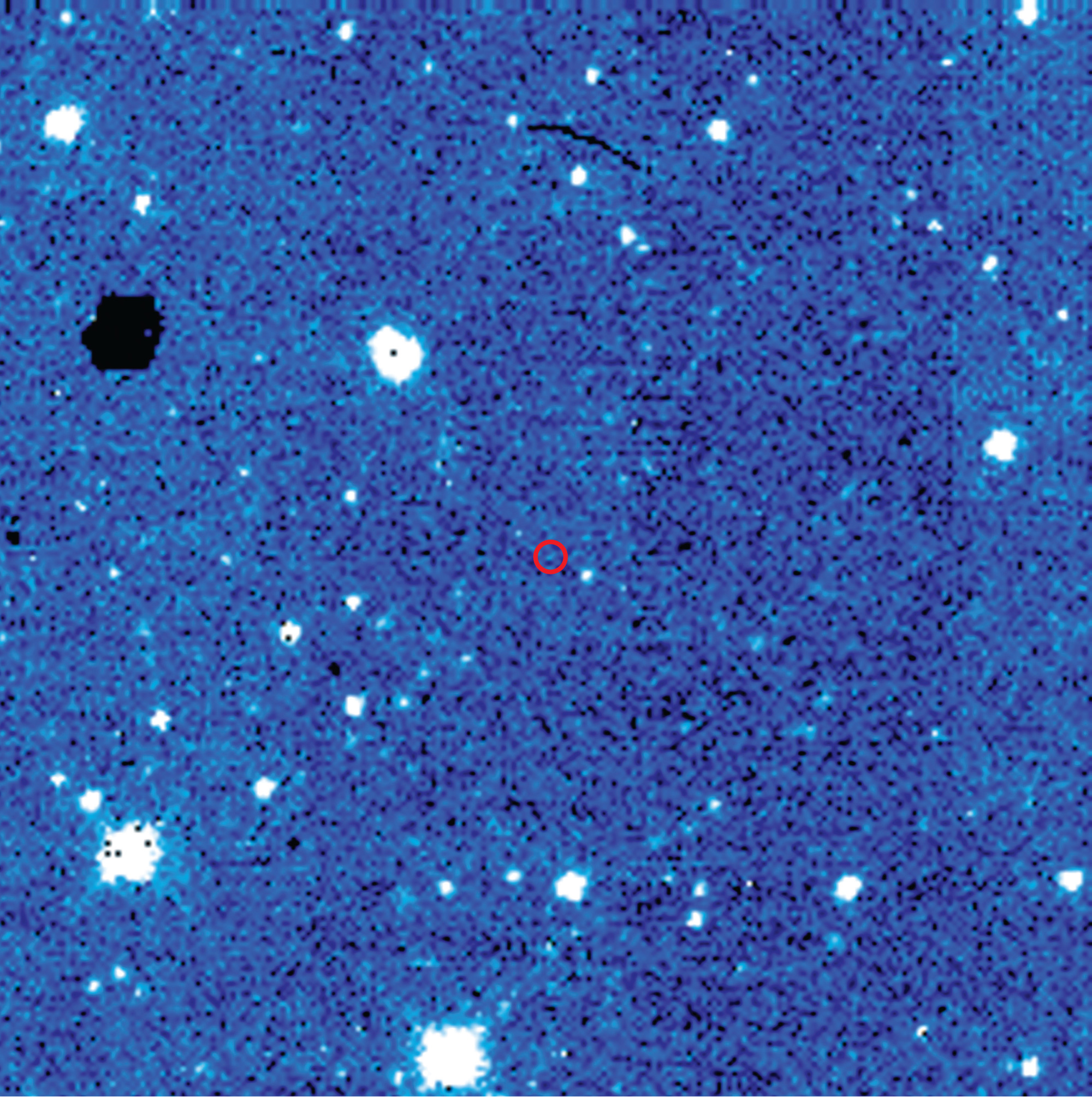

There is a main-belt asteroid of stony composition, roughly four kilometers in diameter, and with an albedo, or solar reflection coefficient, of around 17 percent. It bears the same name as the author of the present article, though with the middle initials eliminated, the first and last names concatenated, and a string of numbers added to the beginning: 13585 Justinsmith. To be more precise, it does not just have the same name as the author, but was in fact named after the author. Its relationship to the author is like that of Colombia to Columbus, or of the Vince Lombardi Travel Plaza to Vince Lombardi: a relationship of eponymy.

“I hope that some people see some connection between the two topics in the title,” is how, in 1970, Saul Kripke began the first of his lectures on “Naming and Necessity.”[1] Plainly, though, it was not necessary that Justinsmith should come to bear my name. The asteroid was first observed in 1993, when I was twenty-one years old and had yet to accomplish anything that would merit so much as an eponymous clod of dirt. According to the rules established by the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, discoverers enjoy the exclusive right of naming for the first ten years, though they may still choose a name after that deadline, pending approval by the IAU’s fifteen-member Committee for Small-Body Nomenclature, if no one else has gone through the complicated steps necessary to do so.[2] In this case, the discoverer, Belgian astronomer Eric W. Elst, would not choose the name until the middle of 2015: it was, after all, only one of at least 3,600 asteroids he had discovered in his long and distinguished career.

While trans-Neptunian bodies may only be named after divinities, main-belt objects—those, that is, generally found orbiting at a distance from the sun somewhere between Mars and Jupiter—may be named after any person, living or dead, who has done anything at all of note, though there is a waiting period of one hundred years after the death of anyone noted for contributions in the field of politics: a measure taken, we may presume, to prevent the partisan carving up of outer space.

Information gleaned from the Internet tells us that Elst is a devoted student of the history of philosophy, and particularly admires Enlightenment-era materialism. He is in fact the founder of the D’Holbach Foundation, dedicated to the study and promotion of the work of the atheistic and radically anticlerical author of the 1770 treatise Système de la nature. In October, having just learned of 13585 Justinsmith, I sent Elst a message care of the Royal Belgian Observatory, from which he had retired some years earlier, expressing my sincere thanks for this great honor, and also explaining that I am not, myself, a materialist, but rather somewhat closer to a phenomenalism of the Leibnizian variety. I cited to him G. W. Leibniz’s motto: “Où il n’y a pas un être, il n’y a pas un être,” which tells us that where there is no true unity, there can be no being. “But material bodies are by definition composite,” I went on, “while only minds or mind-like entities are simple and one. So, if bodies are real, this reality must in some way result from, and be underlain by, minds. This explanation would certainly apply to bodies such as asteroids and planets, not in order to explain them away as illusory (as some versions of idealism might be said to do) but only to provide an adequate account of their nature.” I did not receive a reply.