Leftovers / I Was Opened

The beauty of what remained

Anonymous

“Leftovers” is a column that investigates the cultural significance of detritus.

I repudiate the violence. Now. But then it felt different. Then, we were violent. I was violent. There were those among us who were intent to kill. There were those among us who did kill. This is important to remember. To state. We had, many of us, declared war on the United States. Are you listening? Declared war on the United States. From within. Which is to say, our intention was to destroy the capitalist, racist, imperialist enterprise of Amerika. We thought of ourselves as revolutionaries. We were revolutionaries. Now the preferred term is terrorist. Then, that word was little used. But as currently defined, it fits us, as we were at that time.

We failed, of course. And I have come to believe we were deeply wrong in many ways. We did fundamental wrongs. Crimes. Sins, even. Acts that I would not now try to defend. Shooting people. Bombings. Yes, we were seeking justice—we did these things in the name of “justice.” Yes, we sought an end to the deranged and sadistic and genocidally brutal war in Southeast Asia. Yes, we correctly diagnosed the foundational maladies of the nation: psychotic greed; a schizophrenic yawing back and forth between megalomania and fawning sycophancy; the inbred and delusional fantasy of God’s special love for righteously violent white men. But despite the good intentions and the hard-won insights, we failed. And we failed ugly. One of the ironies? Most of us turned out to be righteously violent white men, enmeshed in delusional fantasies of our own transcending grandeur. We treated the women like shit, and we condescended to our black brothers. But that was the least of it, frankly. After all, the alternative regimes in which we placed our hope were, if anything, still more appalling than the geyser of self-satisfied cruelty we hoped to cap; the ideologies we then espoused have proven, under scrutiny (or is it just ill use?), both dehumanizing and dysfunctional. The toll of the damage we did was, in the end, when one thinks at the scale of nations, worlds, war, relatively small. But had we secured success along the lines of the heroes we lionized, I have no doubt but that the bodies would have been stacked like cordwood. Picture mass graves in the Maoist re-education camps we’d have built in wherever we’d have built them. Georgia. Alabama. Mississippi.

It is difficult to recover the moment. To return to the state of mind, the climate, the sense of possibility. For a time, for two years, really, (perhaps a little more) it seemed as if revolution was actually possible. Was upon us. It seemed that Amerika might fall. The riots of ’68 had given us a taste of our power, and a tiny taste of blood. From there, each incremental high-water mark is a matter of public record. These events are history: the formation of the Weather Underground in the summer of 1969; our clandestine delegations to meet Cuban and North Vietnamese leaders; plans for armed alliance with the Panthers; the “Days of Rage” in Chicago, and mounting clarity that our job was to “bring the war home”—to make the complacent stateside pigs bleed. A severed limb in Khe Sanh, we wished to demonstrate, was phenomenologically no different than a severed limb in Newburyport. Ethically and politically, we believed the latter to be infinitely easier to defend.

So we all became fugitives. By early 1970, the domestic bombing campaign had begun, and plots were afoot for attacks on weapons depots and military bases. Armed robberies (for money to fund the rebellion) and guerilla work by snipers (on police and other agents of the state) would soon follow.

I rehearse these brutal facts in an effort to clear the tiresome miasma of condescension that has descended over the whole enterprise. I watched as the 1980s made the 1970s into an opera buffa of bumbling hippies and blowout afros. We were not ridiculous. We were not some risible clutch of long-haired buffoons, engaged in a collegiate prank that briefly overstepped the threshold of the dormitory (before promptly turning to EST-ing and disco). We struck fear into the hearts of the domestic security establishment. We were dangerous, we were organized, and we were totally committed to the destruction of the established order. This was not some pathetic outtake from The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. This was declared war on a global hegemon. Yes, we failed. But it might have been otherwise. And for a moment, it seemed as if it would be.

Ok, enough with the scene-setting. Let me turn to the matter at hand.

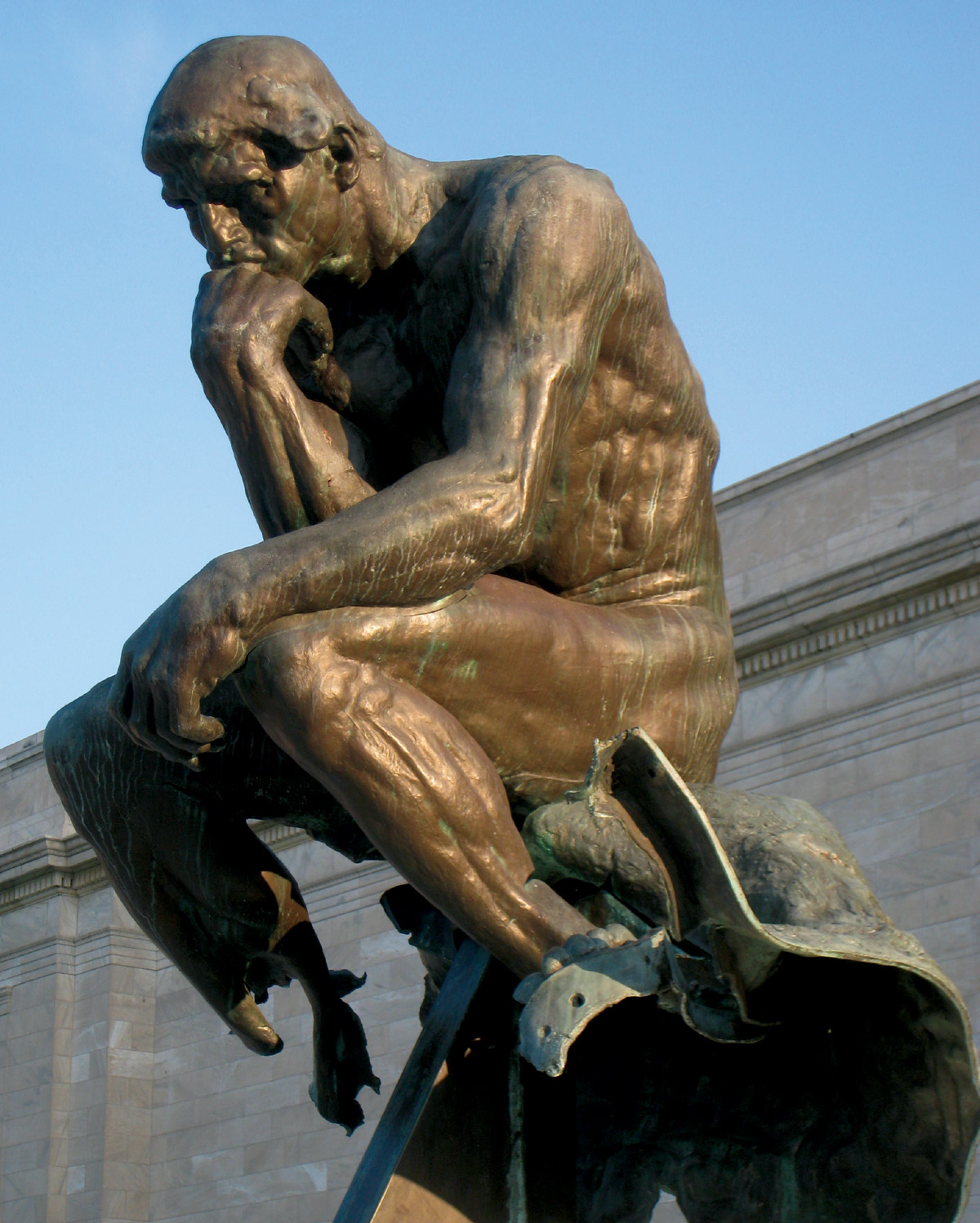

Much of the preparation for the Chicago riots had happened in Cleveland. We had a presence there. Individuals. A penumbral force. And while the highly repetitive and derivative writings on the action of 24 March 1970 never fail to represent the bombing of the Cleveland cast of Rodin’s Thinker as some sort of incomprehensible bizarrerie, the bombing of sculptures was not new. Indeed, just a few months earlier, on 6 October 1969, under cover of night, some of us placed a powerful explosive device between the legs of the towering bronze police officer at the Haymarket in Chicago—six tons of reactionary desecration, casting its fascist salute over the memory of massacred leftist workers. It was utterly destroyed.

As things progressed, though, statues were the least of it. The bloodshed began to shock. To unsettle. Several of the bombs of early 1970 took lives, and there were those among us whose consciences recoiled. The always-heated debates about tactics got hotter. There were many who insisted that if our violence looked indiscriminant, we risked the alienation of the very populations who were within reach, who were on the cusp of radicalization.

This was the context. I don’t remember who first mooted The Thinker as a target, but I certainly remember our conversations. They were rich. They were detailed. They were impassioned. And they were informed. It has never ceased to irritate me that our act has been endlessly depicted as “incomprehensible” or “mad”—as if it were somehow impossible to understand why one would wish to attack a looming figure of brooding “reason.” A brute of green bronze. A bauble of the chattering classes—cast from the stuff of the revolution.

I’ll say it again: I recant; I retract; I regret.

But that does not mean that I forget. So let us recall. Let us reconstruct. Let us recover.

Why did we bomb it? What were we thinking?

As is ever the case with collective action, we came from different directions, and converged only in the act. Nor did we ever achieve anything like consensus as to the rationales for and/or symbolic import of our target. For instance, one of us had recently read Conrad’s The Secret Agent, and had been much taken by Mr. Vladimir’s exhilarating desire to “throw a bomb into pure mathematics.” That being impossible, the anarchists turn to the Greenwich Observatory—both in the novel, and in real life (Conrad based his story on the botched attack on Greenwich by Martial Bourdin in 1894). That set of instruments in that hilltop tower materialized mathematics, and in doing so set the expressive conditions of possibility for hot rage against the logic of abstraction itself, the original sin of indifference to what obtains, a move both invented and nourished by the flight to number. And once we are in the realm of number, we have entered the frictionless spaces of manipulation. There, we may operate upon any and all, in sovereign indifference.

And so there was a mood, among some, that to bomb The Thinker was not simply to blow up the grim figure of surveillant white patriarchy, but actually to blow up thought itself—as the perennial antithesis of action, as the passivity of cognitive withdrawal, as nothing less than the vaunted “inwardness” of bourgeois subjectivity.

But for others this was itself already wholly too abstract as a rationale for the act we were contemplating. Some of these, as I recall, harped on the visage of the figure itself—its actual countenance. In fact, it was perhaps this that first pricked the attention of those who initially proposed the sculpture as a target. It was as if that face, lowered onto the supporting hand, projected a monstrous apartness. Was this merely the inherent viciousness of introspection? The inevitable solipsism? Perhaps. But there was a rebarbative power in it. Something that was received by some in our number as a kind of contempt. I never saw that, myself. But those who did spoke with conviction.

Did we know anything about the sculpture itself? Of course. Yes. We were not ignorant. Our reading was uneven, but we were resourceful. And relentless. The original placement of the figure on the tympanum of the Gates of Hell. Yes. We knew about that. The various interpretations, too: that the figure was Dante himself, surveying the inferno (and, of course, the Inferno) or perhaps better, some universal figure of the poet or artist contemplating human fate and folly. And what about the notion of the figure as the soul itself, perched on the cliff of eternal destiny? Yes. There was discussion of these matters. The richness of the tradition was not lost on us. At stake was the whole awkward contraption of allegory, the whole theological iconography of the West, plus its literary and beaux-arts apotheosis into “humanism.” But this was, for us, hardly exculpatory. On the contrary. It headed the indictment. It was that exact tradition, we had decided, with its fetishistic devotion to the individual, its romantic narcissism, and its bankrupt metaphysics, that had spawned the great dervish of murderous self-justification and mawkish solemnity that was whirling in a pirouette of relentless, profiteering death across the globe.

We knew what we were doing. Or we thought we did.

And so we set the charge. At his feet. By night.

• • •

As a small boy, I recall catching a glimpse of some nature-documentary on television. This was the old days. Divers in a cage used a “bang-stick” on a Great White, and filmed the results. A bang-stick is just a twelve-gauge shotgun shell mounted at the end of a long shaft, and outfitted with a snap-hammer that fires the shell when the stick is poked into something solid. So, it is a way of manually delivering a pointblank shotgun blast. The divers hit the big shark in the mouth, and the shell blew the whole side of the mouth open. I recall so vividly the panicked animal, bolting in wide-eyed circles past the camera, the thin skin of its face billowing loose like wind-blown laundry on a line.

It was this image that returned to me when I saw what we had done. There was something of the same loose billow in the metal that had burst open into a new and fluid form, undulating and suddenly fragile.

The cant and platitudes that greeted our handiwork may be reviewed by anyone who wishes to poke around in the period newspapers. The denunciations. The protestations. The Victorian moralizing. It is all “right,” of course. It is “correct.” The obscenity of what we had become is beyond dispute.

I must nevertheless confess, here, that I fell deeply in love with the object the moment I saw it in the papers the next day, resting in the fetal position at the foot of its own pedestal. This was not something I felt I could discuss with the others—though I know for a fact not one of them ever made another bomb. The whole occasion marked a very real change in our perspective. And it was the beginning of a period of considerable confusion for me, from which I can hardly be said to have emerged.

There have always seemed to be two possibilities. The first, and perhaps the more probable, is simply that the fallen and damaged figure awoke me from my rabid slumbers—that some cold slap of guilt or shame or even, simply, of the grotesque (the absurd?) brought me out of my coarse and chiliastic militancy, if not fully back to my senses (whatever that might mean). But the other possibility is weirder: that it was not the ugliness and incongruity of our act that precipitated my peripeteia, but rather the actual beauty of the thing that remained.

I still find it difficult to say this. It feels awkward. Inappropriate. But I have never really recovered from seeing the thing that resulted from our explosion. It is as if the work had been reborn. Gone was the solid base. Gone the sense of rock-rootedness. Gone the sturdy mass of anchored contemplation. Gone the brooding grandeur, the in-folded masculine brutality curved over sturdy legs. Instead, now, that same broad torso lofted above a kind of open cape, or breeze-lifted skirt. Yes, there is the damage—the shattered legs. But I never look at the work and see a maiming. I see something like a lightness, a liberation, an opening.

When the museum solemnly announced that they would not attempt to repair the damage, but would instead preserve it in its shattered form, they had the audacity to suggest that this was because now it had become a “historical artifact.” I felt a momentary surge of the old rage. The gesture cannot be so easily contained. In fact, I think they secretly know that. They love it. And they don’t dare to admit it.

In his affecting essay “A Few Steps toward an Anthropology of the Iconoclastic Gesture,” the French sociologist Bruno Latour describes the process by which the hammer of the iconoclast can ricochet, can rebound, and shatter not the icon, but the project of icon-shattering. For it is only the iconoclasts, he asserts, who have “naïve” belief: they have naïve belief in the naïve belief of others. This is what the work says when it is struck. When it rings like a gong as it hits the hard earth, forever thereafter to float.

Damage it? We completed it. And ourselves. In a flash.

I return often. Just to look.