Inventory / Two Gardens in Two Books

Early modern herbaria and the question of botanical representation

Bennett Gilbert

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

To describe a plant with words hardly brings a reader close to its mysterious reality. Neither the most specific nor the most allusive words can replace a living presence. Even the simplest being has an elusive, intense reality whose fullness provokes problems of representation, not just for writers but also for artists. In many ways, it is our contingent grasp on life itself, and our fear of its loss, that underlie these challenges to representation, whether it takes the form of mimesis, incarnation, abstraction, or trace.

Botanists who aspire to represent the complexity and beauty of plants in books have typically supplemented their words with visual material. This can take the form of handmade images produced using pencil, ink, crayon, or watercolor; drawings reproduced through such media as woodcuts, engravings, and photographs; or by incorporating actual specimens of plants. Though this last option is, of course, the most direct from of representation, it is also by far the least common method of botanical illustration.

A specimen in the presence of text becomes something other than a plant, though it is a piece of a plant. It turns into a picture. As a picture, it represents the plant’s passage across time, from life to death to image and finally again to a kind of life—at least, life as the specimen-collector chooses to represent it. This trajectory is one that arcs from enchantment to disenchantment and, finally, to re-enchantment—for it seems that something about us can enchant the world, as well as destroy it.

Numerous, sometimes very old, collections of plant materials, known as herbaria, are to be found in the drawers of natural history museums. Yet, in the period of the hand-press book, from around 1450 to around 1820, only two printed books illustrated using dried plant specimens were published.

One of these two efforts has this marvelous title: Herbier forestier, ou Collection des espèces d’arbres et arbrisseaux qui composent les forêts.: Qui mieux encore que ces arbres, les biens qu’ils nous produisent, et leur aspect majestueux, en nous offrant l’un des plus beaux ouvrages de la nature, peut mériter notre vénération, et nous faire connaître la main toute-puissante du Créateur! Dédié et présenté au Roi. Par J.-B. Duchesne fils, jardinier en chef de Sa Majesté. [Forest herbarium, or a collection of the species of trees and shrubs that fill the forests: What could merit our veneration and make known to us the omnipotent hand of the Creator more than trees, the benefits they produce for us, and their majestic aspects, in presenting to us one of the most beautiful works of nature! Dedicated and presented to the King. By J.-B. Duchesne the younger, head gardener to His Majesty.]

Dedicated to Louis XVIII in 1820, the book comprises forty-two large pressed specimens of trees and shrubs cut from the forest that Jean-Baptiste Duchesne supervised for the king. Each sample is sewn with green thread onto heavy white paper on which is printed the specimen’s Latin botanical and French colloquial names; these are in turn placed between two sheets of extra-thick, deep blue Holland paper. The book is bound in gilt-lettered, straight-grained red morocco leather. There is no census of the number of extant copies. The Bibliothèque nationale does not record a copy and only two are known in the United States: one at the Henry E. Huntington Library, Art Gallery, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California; and one in Rachel Mellon’s Oak Spring Garden Library in Upperville, Virginia.[1]

Duchesne wrote detailed texts about the cultivation of trees, such as his Guide de la culture des bois, ou Herbier forestier (1826), but here he clearly had a goal other than direct instruction. Duchesne was making a picture of the beauty of nature through a kind of collage. The lush pages and huge cuttings of this book show us an Elysium of enormous, abundant trees and shrubs: a fully enchanted natural world that has sprung to “majestic aspect” under the protective nimbus of a creator-king. This beautiful world Duchesne made for his king in turn shows us the glory of God.

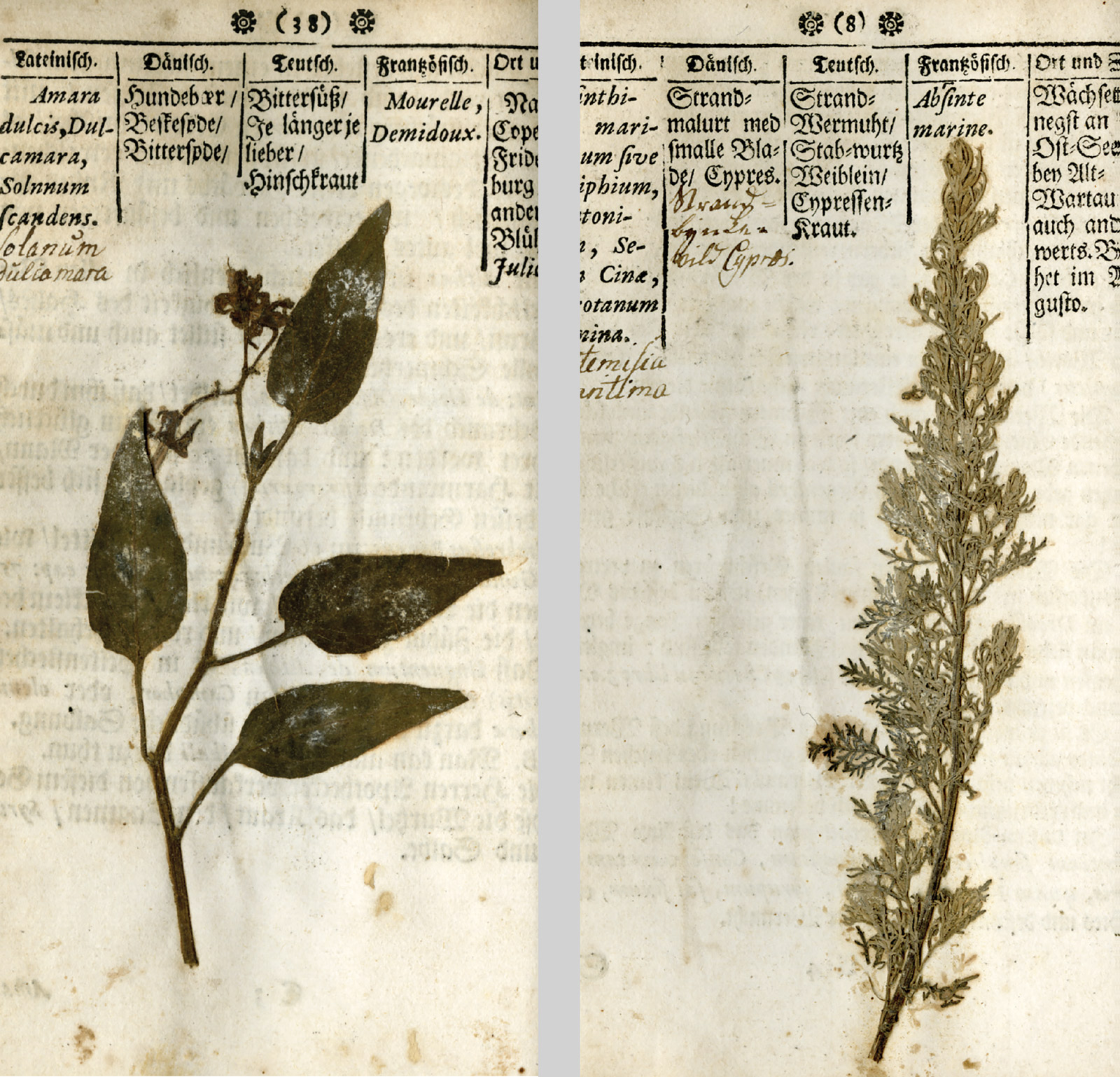

The other book illustrated with dried specimens was designed from a very different point of view. It was not made for the pleasure of a king but for the use of working pharmacologists and botanists. Its plants, however, like Duchesne’s, were also picked from a royal garden—the medical garden of the King of Denmark—in this case by a physician named Balthasar Johannes Buchwald (1697–1763). Printed in Copenhagen in 1720, its title is Specimen medico-practico-botanicum, oder kurtze und deutliche erklärung derer in der medicin gebräuchlichsten und in Dännemarck wachsenden erd-bewächse, pflanzen und kräuter.... [Medical, practical, and botanical specimen book, or, a short and clear explication of the plants and herbs grown in Denmark most commonly used in medicine....]

Buchwald’s view of life, and the mode in which he preserves past life, is quite opposite to Duchesne’s. His book is squat, thick, and dense, rather than tall and grand; the garden it preserves useful, rather than ideal. One would find 239 specimens in a perfect copy; the text for each includes its Latin, Danish, German, and French names plus the months of blooming. The cuttings are glued to the page beneath these lexica, and discussions of therapeutic uses with references to ancient and modern literature are located below the specimens. The columns of text govern the spaces allocated to the specimens, whereas in Duchesne’s book the plants branch as they will, challenging the rectangular page. At least a dozen copies are recorded, many lacking most or all of the specimens, but in a copy held by Stanford University, 218 specimens are present.[2] (The specimen of cannabis sativa, classed by Buchwald as an aphrodisiac, is, predictably, among the missing.)

The practical difficulties of showing what a text talks about by including the actual object under discussion (unless the object is a picture) do not alone account for the rarity of this type of artifact. There is an oddity to mixing ideas and things, as if the author were challenging the immaterial with the material. Mixing them threatens what seems to be immutable—all that which print fixes to the page by the blood-kinship between ink and paper—with what is at the heart of change itself: nature, understood as all that comes to be and passes away. The plants embody the seasons, their color, shape, and mass all decomposing. On Buchwald’s pages, one sees seeds, which should have met damp earth to carry on the lives of the withered leaves next to them. Seeds and leaves both are here sewn onto leaves of another kind, made from plant fibers but dried, clipped, pressed, and compiled. Selection and classification slim the abundance of nature. Even in Duchesne’s Eden, there is melancholy. One feels this loss in the incommensurability between living nature and the human purposes to which it is adapted. Or perhaps, no less sad, mourning can flicker in these leaves because words sometimes have the power to degrade nature. The very memory of nature puts us to shame, reminding us of what we snip and tread, need and destroy.

Buchwald’s world is not completely disenchanted. Words and specimens bring each other to life. The specimens have personality and nourish the words. The book was published during a period marked by an efflorescence of rococo, a style that depicted continuous creation in every part of nature—most famously in motifs such as shells or grottoes. But it was also sometimes based on an imagined, infinitely productive, and motile prime matter called rocaille, a substance that the center of the earth was thought to ceaselessly produce, like tuff out of volcanoes. This style stood athwart mechanism, arguing that it is not causality but deeper sympathies that hold the world together. Rococo artists and thinkers observed nature in a manner characteristic of the eighteenth century (and in some ways much like a modern), but at the same time, they held the view that there is a reality beyond mechanical causation, the principle that formed the basis of the new science of the seventeenth century. They saw life as abundantly interconnected by powers and sympathies, and by words and forms. Buchwald’s pages suggest vitalism as a way of perching at the juncture of the mechanistic and magical views of reality. In these pages, an unyielding hope connects living and dead words, and living and dead matter—a hope presented without glamor or fanfare but as a real, vast, and sustained practice.

In Buchwald’s book, the mise-en-page alters the relationship between the logical order and the temporal order. While the organization of the upper portion of the page is quasi-taxonomic, the words just below the header trail down the pages like catkins or roots, undaunted by the mummified remains of twigs, petals, pods, fronds, blades, and bracts to which they point. They enfold these plants in the diverse conceptions preserved in languages, memories, and traditions, saying: “We hold another kind of life.” Decay becomes merely a tense, interchangeable with a great array of other tenses that can also defy containment or logic. The roots of things—of life and of language alike—are old but current; they always are past, present, and future.

Exactly one century after Buchwald, the bourgeois grandeur of Duchesne’s Herbier projects bland repose but is in fact a more tense and fractious world than it claims to be. We see in Duchesne the evidence of disconnection from nature, a world in which the fashion is not to work with nature, to know its ways and the secret sympathies between plants and us, but instead to observe it from a pleasing distance. To do this, we must set nature as we set a stage or decorate a room, choosing each object for effect and beauty, carefully making their presence seem careless. The art renders the plants harmless, and so they can no longer be our true friends. The least misstep in the floral arrangement spoils the effect, and the customer-king will not be pleased. Its enchantment is over-precious re-enchantment, compensating for the loss of real enchantment, very much like spiritualism and sugary nature-worship in the nineteenth century.

The garden Duchesne invites us to imagine is impressive but restrained by its elegance. Though the size of his cuttings could project the strength of nature, the silence of his pages hides this. It is the Romantic garden, snipped into a pose of naturalness. What Buchwald presents is constructed as well, but according to different rules—those of taxonomy and those dictated by a form of empiricist rigor. And yet, the garden we imagine through his miniature cuttings is more tangled and wild than Duchesne’s because it names the curative and toxic powers of the plants. This accompaniment of words and concepts, quite lacking in Duchesne, makes the profusion on Buchwald’s pages more like that of untended nature. Here, words and facts give us something powerful that refined sentiment does not offer. They express how to grasp nature while deepening our view of its creative force, which endures and extends far past our efforts to hold it still.

- The Huntington copy is described in the online catalogue at http://catalog.huntington.org/search?/l499479. In An Oak Spring Sylva (Upperville, VA: Oak Spring Garden Library, 1989), Sandra Raphael notes that the specimens in the Oak Spring Garden Library copy include “main forest trees (oaks, beech, ash, chestnuts, birches, hornbeam, elm); secondary ones (poplars, limes, alder, willows, acacia (that is, robinia), sycamore, field maple, service trees, horse chestnut, wild apple and cherry, walnut); main forest shrubs (hazel, hawthorn, dogwood, cornel, wild medlar, blackthorn or sloe, privet); and secondary ones (black alder, purging buckthorn, wayfaring tree, spindle tree, barberry, briar rose, holly, box).”

- A digitized copy of a 1721 edition at the university library of Erlangen-Nürnberg is available at http://digital.bib-bvb.de/publish/content/14/12779553.html. The Stanford copy, also a 1721 edition, is described in the online catalogue at https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/2944618.