The Onion

Peeling back the layers

Implicasphere

Unlike the plum or the mouse or the pebble-dashed house—whose exterior belies its inner form—the onion seems a pure example of material integrity. Once the papery skin is discarded it appears to be every inch itself, formally identical through to its innermost layers. Implicasphere’s mission to glean the full flavor of a word by making a casserole of its various associations would seem simple then, especially as we have confined ourselves to the common “garden” or “bulb” onion, neither dallying with the scallion nor other alliums. So, we march out like Baden-Powell’s blindfolded scouts, sniffing our way along a trail of onion-scent, smeared on the passages and gateposts of language in pursuit of the prize of understanding. But once within our grasp, if the onion does have a fundamental meaning this eludes us as we endlessly peel away at it.

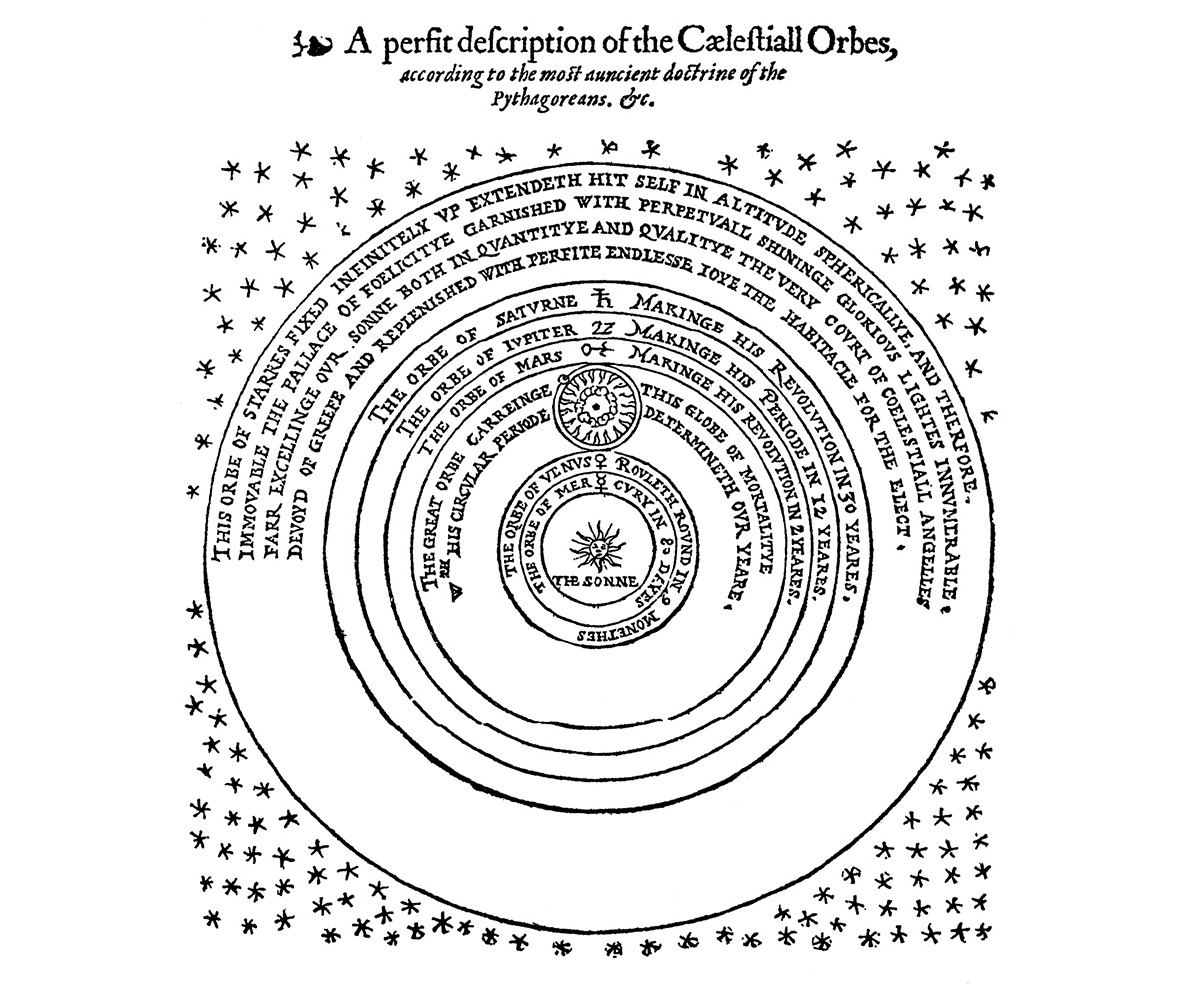

As a topological metaphor the onion is ripe for scientific thinking. It lends its name to the nanoscopic carbon rings in interstellar dust as well as to the structure of dying stars, while its formal resemblance to our understanding of the cosmos was made clear as early as the first English publication of the Copernican model of the universe in 1576. The onion’s symbolism in art, however, is more unstable and discordant. Literary theorist Roland Barthes pits his semiotic onion—with its manifold but centerless layers—against the apricot of classical epistemology and its claim for a center-stone of truth. Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt compares his own being to an onion, his failure to find a kernel of soul revealing he is no more human than a troll; conversely the movie character Shrek uses an ontological onion to demonstrate his ogre soul has depth. The Incredible String Band’s 1967 album title The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion promotes it as a Western rendition of the lotus flower, symbolizing the unfolding of the spirit toward enlightenment. But we learn that James Joyce’s onion in Ulysses is an altogether more pungent version of the mystical lotus.

Beyond metaphor and besides its global status as a culinary staple, the onion is perhaps most notorious as the raiser of mists in the eyes. How to counter its lachrymatory effect is the subject of much conjecture—some say put a piece of bread in your mouth or run cold water over your wrists. But in our emotionally stilted age an onion-stimulated catharsis might be encouraged. In Günter Grass’s fictional Onion Cellar, contemporary real-life Japanese crying bars, and London’s decadent Last Tuesday Society, the collective blub is purposely provoked by chopping the sulphurous bulb, its vapor dissolving the veil of civilized life. Counter to the onion’s communalizing capacity, however, are its ostracizing, derogatory connotations: while at the top of the pile we have those who know their onions, at the bottom languishes the lunatic bonce of the village onion-head or the drunk who is off his onion. No matter how we slice or dice the onion it remains ever stratified with contradiction.

The onion, now that’s something else.

Its innards don’t exist.

Nothing but pure onionhood

fills this devout onionist.

Oniony on the inside,

onionesque it appears.

It follows its own daimonion

without our human tears.

Our skin is just a coverup

for the land where none dare go,

an internal inferno,

the anathema of anatomy.

In an onion there’s only onion

from its top to its toe,

onionymous monomania,

unanimous omninudity.

—Wislawa Szymborska, “The Onion,” View with a Grain of Sand, trans. Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh (London: Faber & Faber, 1996).

The guests peeled the onions. Onions are said to have seven skins. The ladies and gentlemen peeled the onions with the paring knives. They removed the first, third, blond, golden-yellow, rust-brown, or better still, onion-coloured skin, they peeled until the onion became glassy, green, whitish, damp, and water-sticky, until it smelled, smelled like an onion. Then they cut it as one cuts onions, deftly or clumsily, on the little chopping boards shaped like pigs or fish; they cut in one direction and another until the juice spurted or turned to vapour—the older gentlemen were not very handy with paring knives and had to be careful not to cut their fingers; some cut themselves even so, but didn’t notice it—the ladies were more skilful, not all of them, but those at least who were housewives at home, who knew how one cuts up onions for hash-brown potatoes, or for liver with apples and onion rings; but in Schmuh’s Onion Cellar there was neither, there was nothing whatever to eat, and anyone who wants to eat has to go elsewhere, to the “Fischl,” for instance, for at the Onion Cellar onions were only cut. Why all these onions? For one thing, because of the name. The Onion Cellar had its speciality: onions. And moreover, the onion, the cut onion, when you look at it closely … but enough of that, Schmuh’s guests had stopped looking, they could see nothing more, because their eyes were running over and not because their hearts were so full; for it is not true that when the heart is full the eyes necessarily overflow, some people can never manage it, especially in our century, which in spite of all the suffering and sorrow will surely be known to posterity as the tearless century. It was this drought, this tearlessness that brought those who could afford it to Schmuh’s Onion Cellar, where the host handed them a little chopping board—pig or fish—a paring knife for eighty pfennigs, and for twelve marks an ordinary field-, garden-, and kitchen-variety onion, and induced them to cut their onions smaller and smaller until the juice—what did the onion juice do? It did what the world and the sorrows of the world could not do: it brought forth a round, human tear.

—Gunter Grass, The Tin Drum, trans. Ralph Manheim (London: Secker & Warburg Ltd, 1962).

DOCTOR: One last question. It may sound silly, but, um, have you imagined recently that you’ve smelt something that couldn’t possibly be there?

PETER: What an extraordinary thing.

JUNE: What is?

PETER: How did you know?

DOCTOR: It was a long shot. You have.

PETER: Yes, but it’s so silly I would never have told you.

DOCTOR: It’s important. It might explain everything abnormal that you’ve seen and heard.

PETER: Well, that would be a relief, but it still can’t explain how I can jump without a parachute and be alive.

DOCTOR: No, it couldn’t do that. But there might be a possible explanation even of that. Now, this heavenly messenger, you saw him quite clearly?

PETER: I told you, as clear as I see you.

DOCTOR: And this smell you imagined, was it at the same time?

PETER: Yes, it was particularly strong.

DOCTOR: Was it a pleasant smell?

PETER: Yes.

DOCTOR: Could you place it?

PETER: Fried onions.

—Dialogue from A Matter of Life and Death, 1946, written and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

According to [Honoré de] Balzac’s theory, all physical bodies are made up entirely of layers of ghostlike images, an infinite number of leaflike skins laid one on top of the other. Since Balzac believed man was incapable of making something material from an apparition, from something impalpable—that is, creating something from nothing—he concluded that every time someone had his photograph taken, one of the spectral layers was removed from the body and transferred to the photograph. Repeated exposures entailed the unavoidable loss of subsequent ghostly layers, that is, the very essence of life.

—Félix Nadar, “Nadar: My Life as a Photographer,” trans. Thomas Repensek, October, no. 5 (Summer 1978).

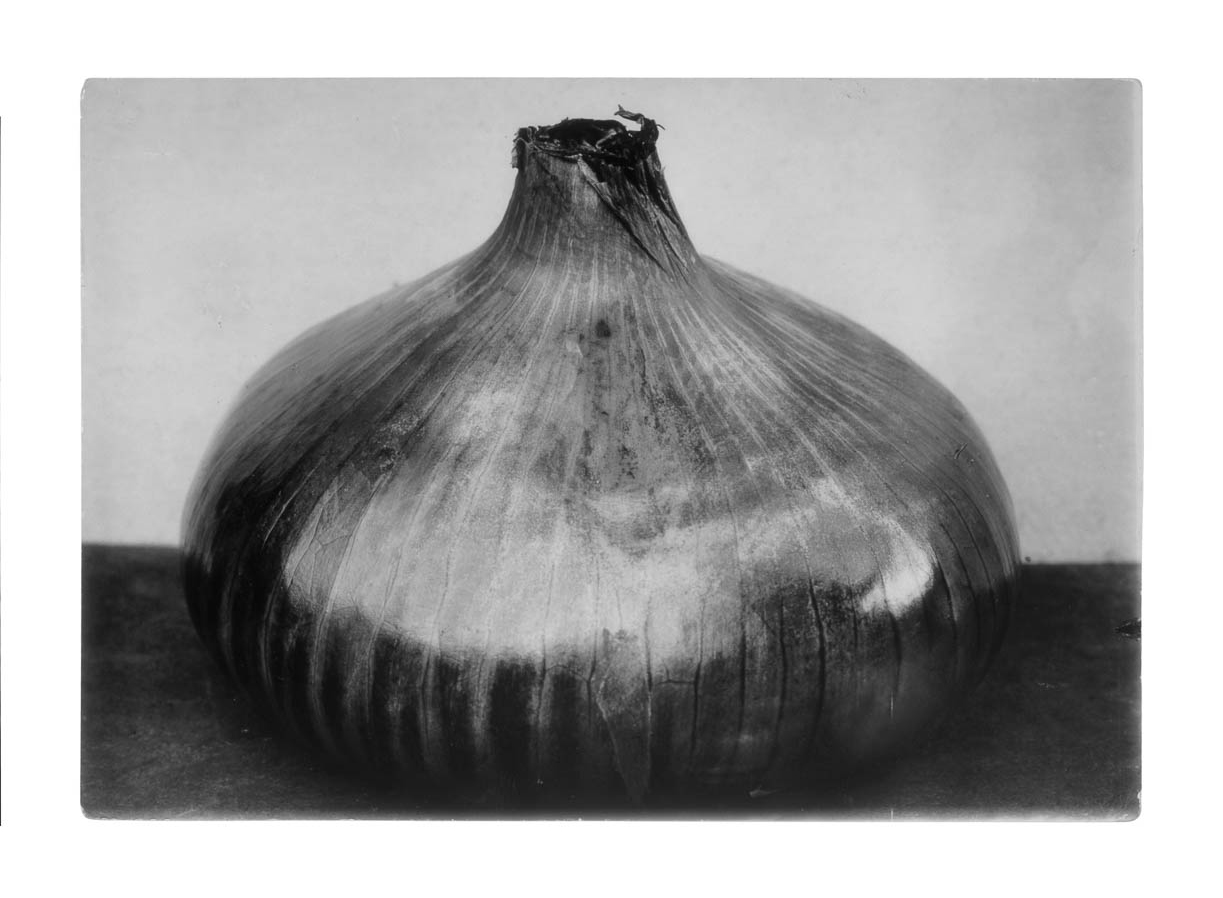

More than 20 years after [Charles] Jones’s death, the photographic historian and collector, Sean Sexton, came across a trunkful of his prints [at Bermondsey Market], about 500 of them, but unfortunately not dated. None of the original glass negatives was with the prints and none has yet come to light. …

[The gardener-photographer’s youngest daughter] Kathleen [recalls] the poignant image of Jones’s precious glass plates, the original negatives from which he made his prints, propped up as makeshift cloches. In his garden, the ghostly spectres of onions past sheltered the emerging seedlings of onions present from the vicious east wind of the Fens.

—Anna Pavord, “Best in Show,” The Independent Magazine, 19 May 2007.

There is a tablet on the pyramid inscribed with Egyptian letters, and which details the amounts spent on radish, onions, and garlic for the workers.

—Herodotus, Histories, Book 2, trans. G. Woodrouffe Harris (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1906).

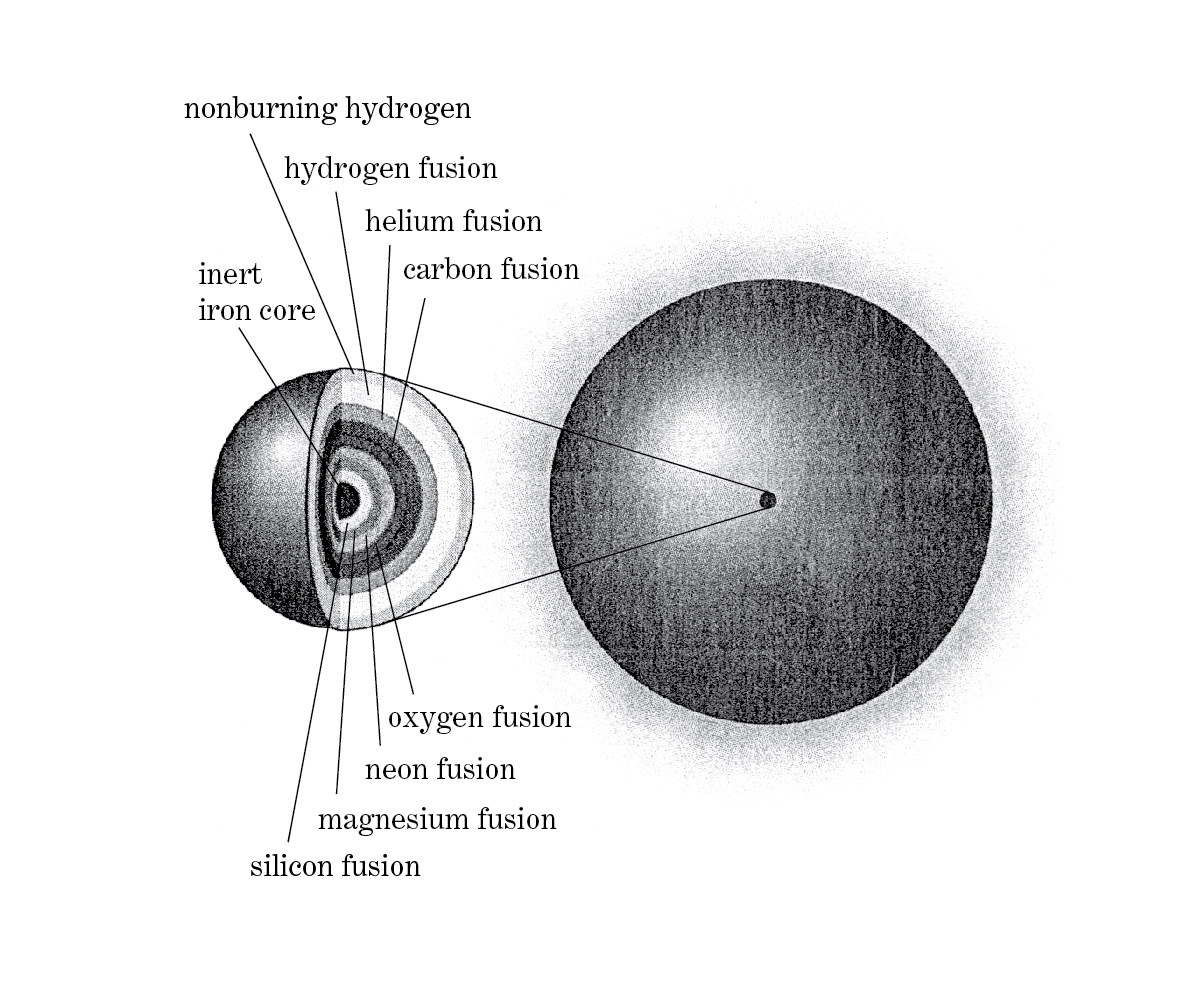

The multiple layers of nuclear burning in the core of a high-mass star during the final days of its life. ... The star’s central region resembles the inside of an onion.

—Jeffrey Bennett, Megan Donahue, Nicholas Schneider, and Mark Voit, The Essential Cosmic Perspective (New York: Pearson, 2007).

The wettest June on record and a below-par July so far mean that most crops are suffering at a time when demand for them is unseasonably high.

“In a normal year, the industry would be looking forward to the harvest of the early-season crop,” said Tim Wigram, chairman of the British Onion Producers’ Association (Bopa). “But the abnormally wet and dull weather of the last eight weeks has started to have a serious effect.” …

If there are further rainfalls over the next two weeks, Bopa fears there could be a further detrimental effect on both volume and internal quality as well as a risk to the external appearance of bulbs through staining.

—Kathy Hammond, “Vegetable Alarms Ringing,” Fresh Produce Journal, 14 July 2007.

What is the fate of stars that cannot settle down to a quiet retirement as a white dwarf? Stars more massive than a few solar masses experience more phases at the ends of their lives, going through one nuclear fuel after another to battle the crush of gravity. After the star’s helium is exhausted, the core contracts and heats again, and the outer layers expand, sending the star up the asymptotic giant branch of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram [which shows some of the stars of M3 (an old globular cluster) and plots those that have left the main sequence to form a horizontal and a giant branch]. In very massive stars, carbon may first ignite; for sufficiently massive stars, increasingly heavy elements are subsequently burned, fusing all the way to iron. The star becomes a gigantic cosmic onion, consisting of concentric shells in which increasingly heavier elements are fused. The final product is iron. Unlike the lighter elements, iron demands an input of energy to be forced to fuse into heavier elements. Iron cannot provide the energy the star needs so desperately to support its weight, since further fusion would actually consume the star’s precious energy. Once the available matter has been burned to iron, the star is out of usable fuel; iron is the end of the nuclear road.

—John F. Hawley and Katherine A. Holcomb, Foundations of Modern Cosmology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

ONION SKINS. (Brown.) Mordant the wool with alum and a little cayenne pepper. Boil it up lightly and keep warm for 6 days. Drying 2 or 3 times in between makes the colour more durable. Dry. Boil a quantity of onion skins and cool; then put in wool and boil lightly for half-an-hour to an hour; then keep warm for a while. Wring out and wash.

—Ethel M. Mairet, A Book on Vegetable Dyes (London: Douglas Pepler, 1916).

Slice ½ pound (250 grams) of onions finely and fry in butter, cooking them through thoroughly but without allowing to colour too much.

When the onion is nearly done, sprinkle it with 2 tablespoons (25 grams) of flour. Stir with a wooden spoon for a few moments. Add 2 quarts (litres) of white consommé or, if soup is tended as a Lenten dish, an equal quantity of water. Cook for 25 minutes. Pour this soup (strained or not, as preferred) over slices of bread dried in the oven.

—Prosper Montagné, Larousse Gastronomique, trans. Nina Froud et al., ed. Charlotte Turgeon and Nina Froud (New York: Crown Publishers, 1961).

You are a roast beef I have purchased

and I stuff you with my very own onion.

—Anne Sexton, “Buying the Whore,” Anne Sexton: The Complete Poems (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981).

There are many different kinds of onions in [James Joyce’s] Ulysses. They are objects of consumption, markers of religious affiliation and of “raw” sexuality, and, in their most elevated incarnation, onions are associated with different notions of subjectivity. …

[That] the Spanish onion comes to stand in for Bloom’s wife, Molly, … is made clear in “Ithaca”—the question and answer section of Ulysses. In it, we’re provided with an inventory of Bloom’s kitchen dresser: “two onions, one, the larger, Spanish, entire, the other, smaller, Irish, bisected with augmented surface and more redolent.” In this instance, Joyce tropes on the notion of an onion-skin theory of identity, the folds and involutions of transparent skins that make up a life. Those two onions in the kitchen dresser are representations of Molly and Bloom. Not only has Molly’s “Spanishness” been emphasized in the previous chapter—“large” and “entire” in the “fullness” of Bloom’s fantasy of her as Moorish queen (she even wears peau d’Espagne perfume)—but also Bloom’s nostalgia—he’s overly “redolent” (full of memories) of Molly. Furthermore, the “bisected” “Irish” onion aptly describes the conflicted and divided subject Bloom, who is both Irish and Jewish. In “Cyclops,” a chapter that isn’t focalized through Bloom, but through a local barfly, Bloom is referred to as “a half and half” and as “[o]ne of those mixed middlings.” Although both epithets in their context refer to Bloom’s ambiguous sexuality, they also reveal his dual ethnic identity. …

Spanish onions return as a prop in “Circe,” Joyce’s nighttown chapter, which takes place in Bella Cohen’s brothel: “[Myles Crawford’s] scarlet beak blazes within the aureole of his straw hat. He dangles a hank of Spanish onions in one hand and holds with the other hand a telephone receiver nozzle to his ear.” Embedded in these stage directions is Joyce’s reference not only to Molly Bloom, that “hank of Spanish onions,” but also to her lover Blazes Boylan, with his “scarlet beak”—here the onion is a placeholder for genitalia. Indeed, if the onion stands in for human subjectivity, then it’s most readily tied to sexual identity. …

As I have already suggested, Bloom—in his “bisected” onion state—straddles national boundaries (the theme is reprised in “Circe” in its evocation of the new “Bloomusalem”); he also blurs the borderlines of gender definition, offering a new kind of sexuality. Nationality and sexuality understood as discrete and bounded can only be whole in myth. Words may temporarily mask division—“the womanly man” and the new “Bloomusalem”—but the subject, Bloom, remains divided, with multiple layers. Finally, at the risk of fetishizing the onion, the world of Ulysses is an Irish onion: bisected (conflicted in its relationship to home and abroad), with an augmented surface (polysemous, multiple, circular, centreless). “For a person who has never seen the Orient, Nerval once said to Gautier, a lotus is still a lotus; for me it is only a kind of onion” (qtd. in Edward Said, Orientalism). If Nerval signals his disenchantment with the lotus by likening it to the common garden onion, then I’d like to suggest that Joyce celebrates a “kind of onion” as having more significance than an Egyptian lotus ever could.

—Alexandra Neel, “Orientalism in Joyce’s Ulysses,” undergraduate thesis (Cambridge University, 1995).

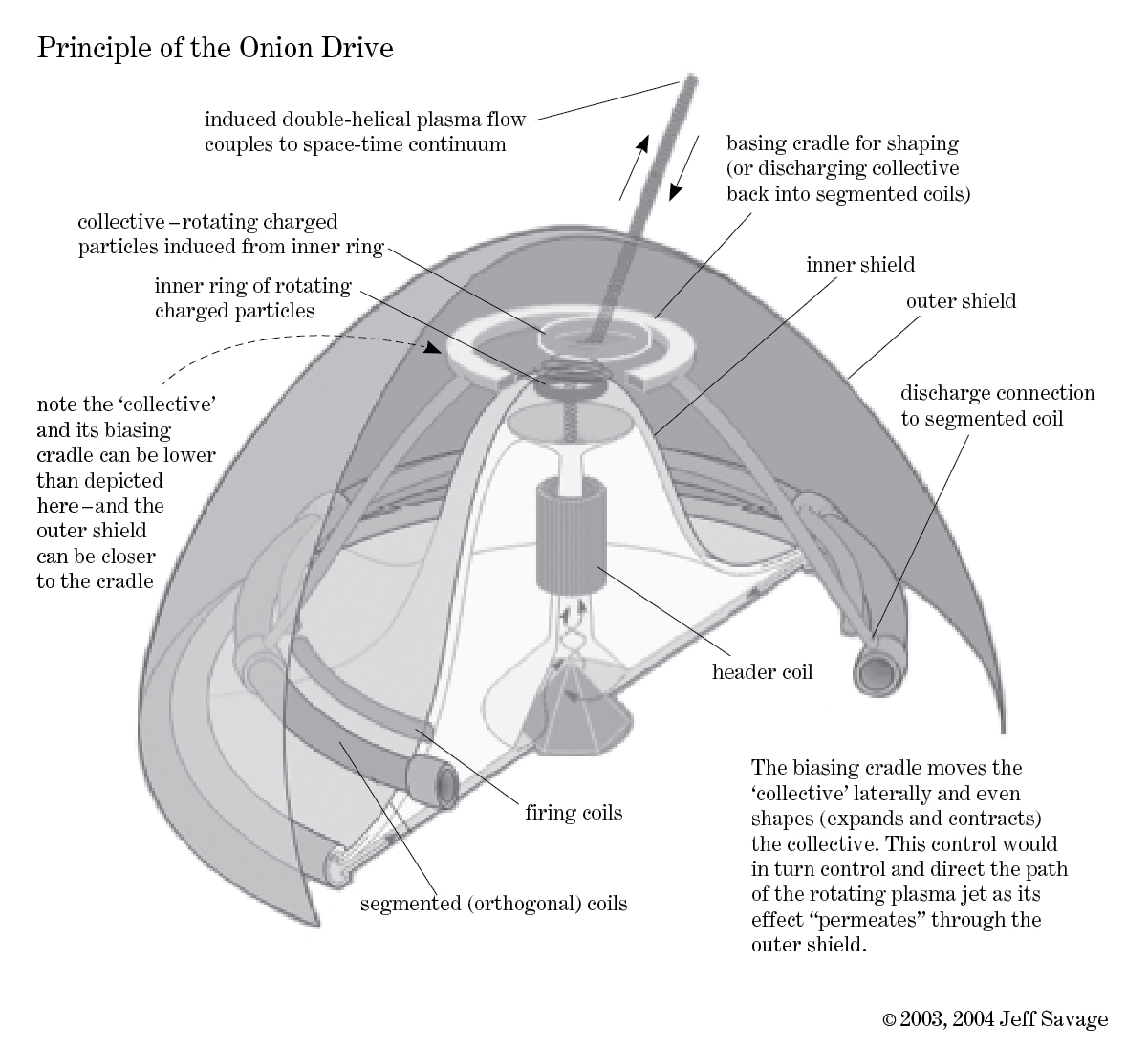

From a study of the very comprehensive technical information and diagrams, supplied recently by Jeff Savage and his associate Richard Robson, it soon became apparent, to me at least, that although there are many different designs to observed UFOs most all of them share a common set of attributes regarding the energy flow configuration they use to move through the air with, even though each individual design of UFO arrives at that energy flow configuration in different ways. Consequent to the above discovery it would seem that the various drive systems of UFOs, whether disc shaped or orb/globe shaped, all generate a rotating EM [electro-magnetic] field which at its source in the center of the craft, is configured in such a way as to disassociate, or disassemble, atomic particles so that an imbalance is created within the craft with respect to positive and negative charges and also, with respect to the ambient atmosphere external to the craft. At the same time by generating this rotating magnetic field—that is now turning a polarized electrical field (confined within the center of the craft)—the whole EM field is speeded up until there results a vortex “jet” or “filament” extending out from the top (usually straight up from the top but it can be angled) of the UFO.

—Paul E. Potter, “The UFO Onion Drive System,” 2004. Available at thelivingmoon.com/41pegasus/01archives_local/Onion_Drive.htm.

SYMPATHETIC INK

FLUORESCENCE (Visibility to naked eye under Ultra-Violet light)

BEST DEVELOPERS

Onion Juice

Yes

Iodine Fumes

Heat

Ultra-Violet Light

Onion Juice & Saliva

Yes

Ultra-Violet Light

Heat

Iodine Fumes

—“Secret Inks,” SOE Syllabus: Lessons in Ungentlemanly Warfare, World War II, 2004.

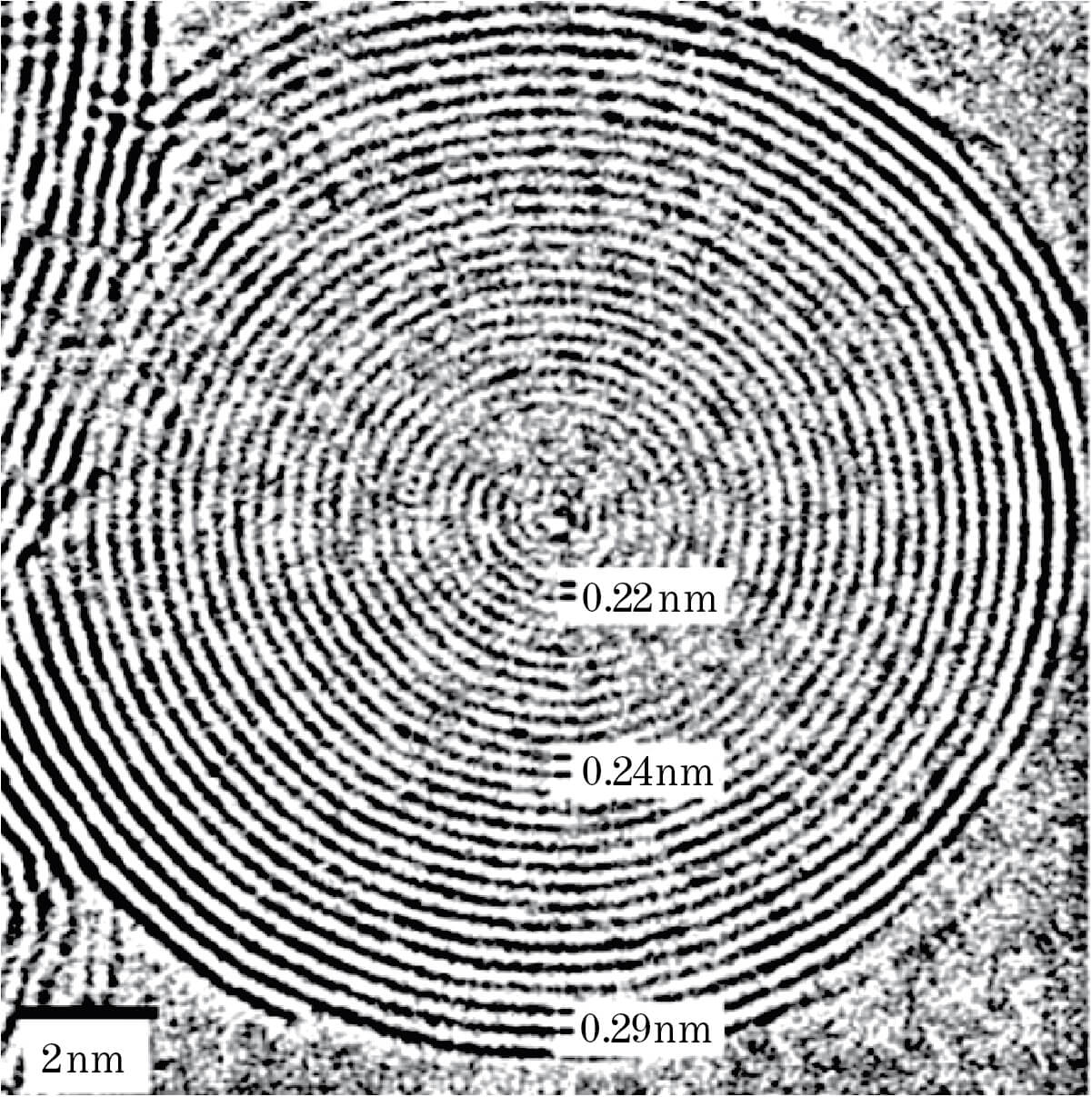

Intense electron irradiation of amorphous or graphitic specimens in an electron microscope results first in graphitisation (when an amorphous precursor is irradiated), then curling of the graphene planes, and finally closure, leaving perfectly spherical concentric-shell graphitic onions.

When such an irradiation experiment is carried out at specimen temperatures above 400°C, no defect clustering takes place and the shells of the onions are perfectly coherent. Careful examination of such onions reveals the unique property of self-compression during irradiation. This manifests itself by the reduction of the spacing between the shells below the usual layer spacing of crystalline graphite (0.335 nm). This phenomenon can be explained by the permanent loss of atoms in the outer shells as a result of sputtering by the electron beam. When two adjacent carbon atoms in a shell are missing (a divacancy) the shell can close again by reducing the number of faces.

—Florian Banhart, “Carbon Onions and Diamond Nucleation,” n.d.

It all began in 1756. Friedrich Siegfried Zweibel, an Immigrant tuber-farmer from Prussia, shrewdly bartered a sack of yams for a second-hand printing press and, according to legend, named his fledgling newspaper The Mercantile-Onion after the only words of English that he knew. …

Herman Ulysses Zweibel, my father and the grandson of the founder, took the reins in 1850, and I grew up under his astute tutelage. Upon my father’s death in 1896, I assumed the editorship, and although reverent of my father’s great memory, I wished to modernize the newspaper a bit. Rechristening it The Onion, I moved the operations to the bustling new industrial metropolis whose name I forget, but it was an electric place where the smell of rancid cow entrails and human feces intermingled in a distinct aroma that invigorated the spirit. As I look back, I realize that these were the golden years of The Onion. I was in the bloom of youth, and, with our ever-growing profits, increasing prestige, and strategic garrotings of various rivals in the newspaper trade, we stood poised at the brink of the Twentieth Century, ready to take it on and make it our own.

—T. Herman Zweibel,“An Introduction,” Our Dumb Century: The Onion Presents 100 Years of Headlines, ed. Scott Dikkers (London: Boxtree, 1999).

Onion Raw

Onion Fried

in Oil

Pickled Onion

(All average size)

Energy (Kcal)

54

66

4

Protein (g)

1.8

0.9

0.1

Carbohydrate (g)

11.9

5.9

0.7

Sodium (mg)

5

2

68

Calcium (mg)

38

19

3

—From Dave Hamilton, “Onions Allium cepa,” Selfsufficientish, 6 July 2008. Accessible at selfsufficientish.com/main/2008/07/onions-allium-cepa-by-dave-hamilton.

British farmers have developed a new kind of onion, called “Supasweet” onion. It is said to be so mild that it can be eaten like an apple. “Supasweet” onions have been available in supermarkets around England since August 2003. The onion has a pale, thin skin, is easy to peel and quick to prepare. “Supasweet” onions are not genetically modified. Their secret is that they have been specially grown in low-sulphur soils!

—The Knowhow Team, “Why Do Onions Make Us Cry?,” The Telegraph (Kolkata), 13 August 2007.

An onion may make you cry—but it could also boost your memory, scientists said yesterday.

Eating the vegetable was found to help people suffering from memory loss.

The Japanese study could be useful in the fight against brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

An antioxidant in onions is thought to flush harmful toxins out of the brain.

But food expert Ian Marber warned last night that overcooking them may destroy the memory-helping properties.

They should instead be cooked on a low heat.

—The Sun, 11 September 2007.

[Honoré de Balzac’s] dinner parties often had themes. Once he served a meal of nothing but onions: onion soup, his favourite onion purée …, onion juice, onion fritters and onions with truffles. The idea was to showcase the purgative properties of the vegetable. It worked. All his guests were sick.

—Bee Wilson, “La gastronomie humaine,” New Statesman, 19 July 1999.

Rooti Frooti. Fresh and juicy

Let me see that Onion Booty!

Woh oh oh, see you coming down the street

Onion Booty looking so sweet

Tears of mine, you gotta give me a break

’Cause I know you got fries

To go with that shake

Boomshackalacka

—The Kingpinz, “Onion Booty,” on Double Phatinum, 2002.

[In] my opinion [the vision of style] must consist today of seeing style as one of a number of textual elements: a number of semantic levels (codes), the interweaving of which forms the text, and a number of citations which reside in that code which we call “style” and which I should prefer to call—at least as a first object of study—literary language. The problems of style can only be treated by reference to what I shall refer to as the “layeredness” (feuilleté) of the discourse. And to continue the alimentary metaphor, I will summarize these few remarks by saying that if up until now we have looked at the text as a species of fruit with a kernel (an apricot, for example), the flesh being the form and the pit being the content, it would be better to see it as an onion, a construction of layers (or levels, or systems) whose body contains, finally, no heart, no kernel, no secret, no irreducible principle, nothing except the infinity of its own envelopes—which envelop nothing other than the unity of its own surfaces.

—Roland Barthes, “Style and Its Image,” Literary Style: A Symposium, ed. Seymour Chatman (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1971).

The mathematic may approximate

And clue us into but may never mate

Exactly: bulb, root, fruit of the fortunate fall

that feeds us with the weeps and utter tang

Of ovoid circles and the slipshod squares,

Triangles rounded at their corners, space

Geometrized resisting its geometry

Imperfectly, as it was meant to do—

—Howard Nemerov, “Inside the Onion,” Inside the Onion (New York: The University of Chicago Press, 1984).

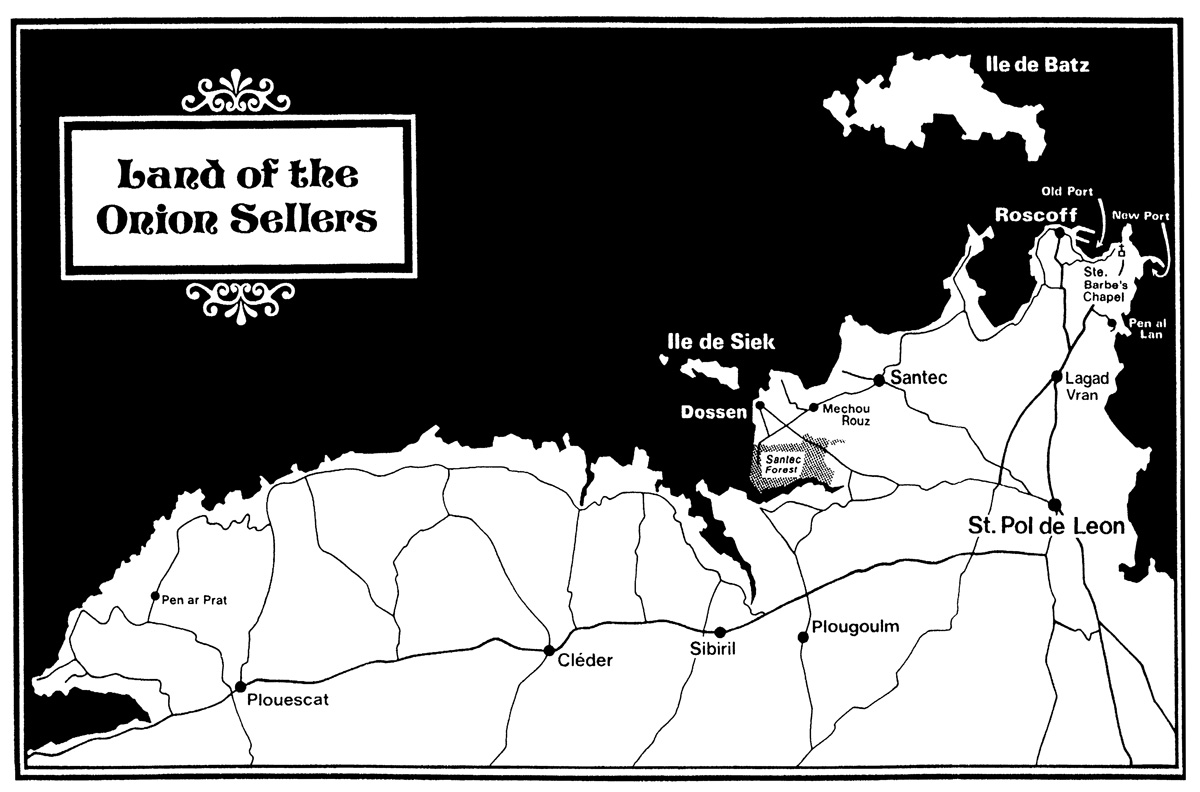

For the five months from September to January 1977–78, 253 Bute Street provided shelter and a storehouse for Jean-Marie Cueff and Olivier Bertevas on what was to prove their last visit selling onions in Cardiff. This was their base, whether they wheeled their onion laden bicycles through the streets of Cardiff or whether they hired a car to pay a swift visit to Brynmawr, Merthyr, Bridgend, Aberdare, or Ystrad Mynach. Their pronunciation of the Welsh place names is perfect and their accent pure valleys but with a slight French “soupçon.” Alone, they always speak Breton, the gruff accents of true “Leonards.” …

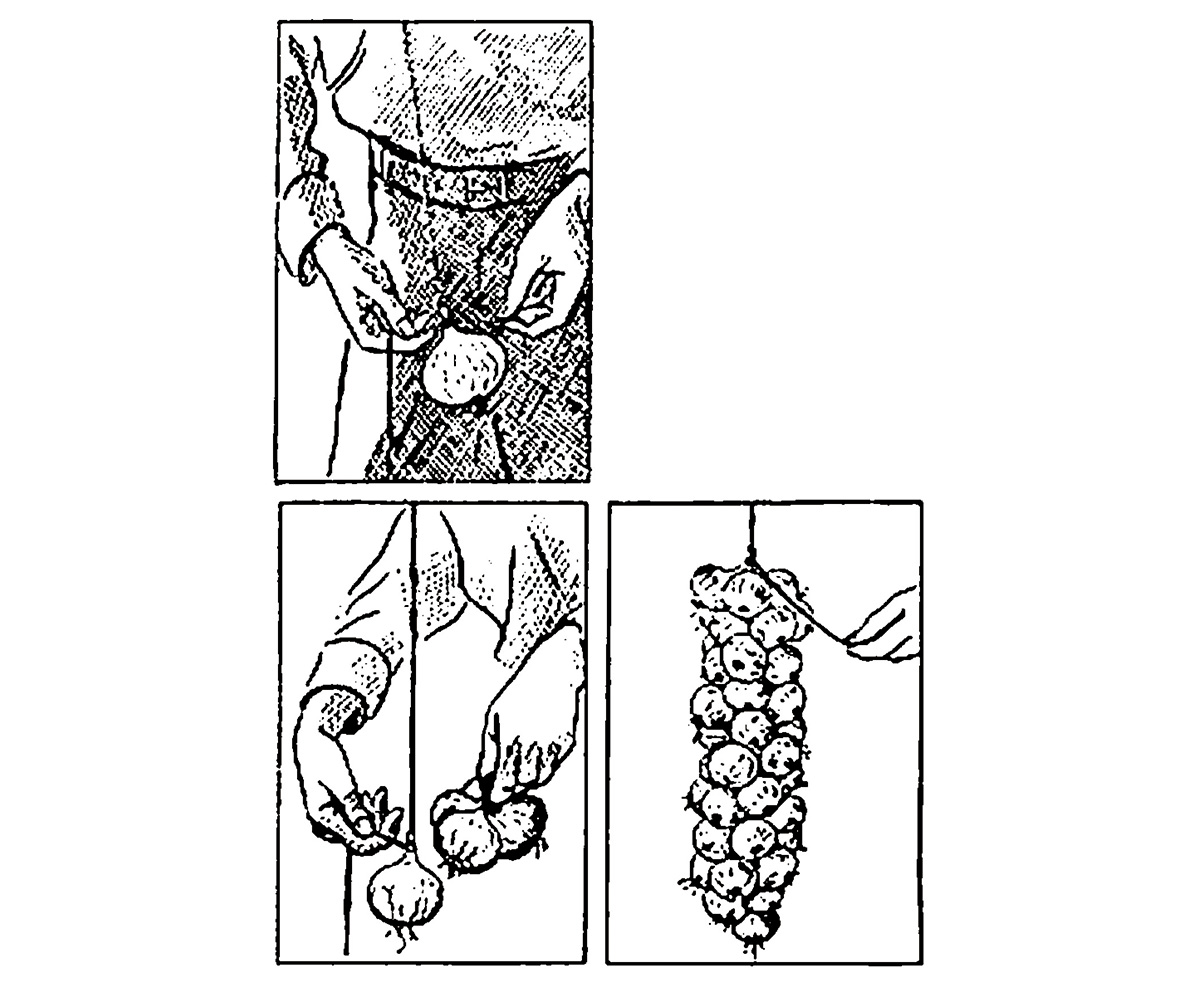

In the back room the two are stringing onions. They use rushes and bits of raffia. … They string the onions rapidly without interrupting their conversation—six or seven rushes, a piece of raffia, a large onion at the bottom as an anchor, then small onions round the bottom of the string with larger onions as they get near to the top. Two single strings are then tied together to make a double string which can be draped over the handlebars of a bicycle. There is no sign of a scale but I feel certain that if we were to weigh a number of strings they would be almost identical in weight.

—Gwyn Griffiths, Goodbye, Johnny Onions (Redruth, UK: Dyllansow Truran, 1987).

Peel the onions and cook slowly in boiling water and salt for about one-and-a-half hours. Drain, and serve with White Wine Sauce.

—H. H. Tuxford, Miss Tuxford’s Cookery for the Middle Classes (Including a Few Vegetarian Dishes) (Manchester: John Heywood, 1931).

Gilt frames should be dusted and brushed over with onion water. Slice and boil a large onion in 1 pint water. Apply the liquid lightly, leave to dry, then rub with a clean cloth.

—Helen Burke, One Thousand Hints for Housewives (London: Waterlow & Sons, 1934).

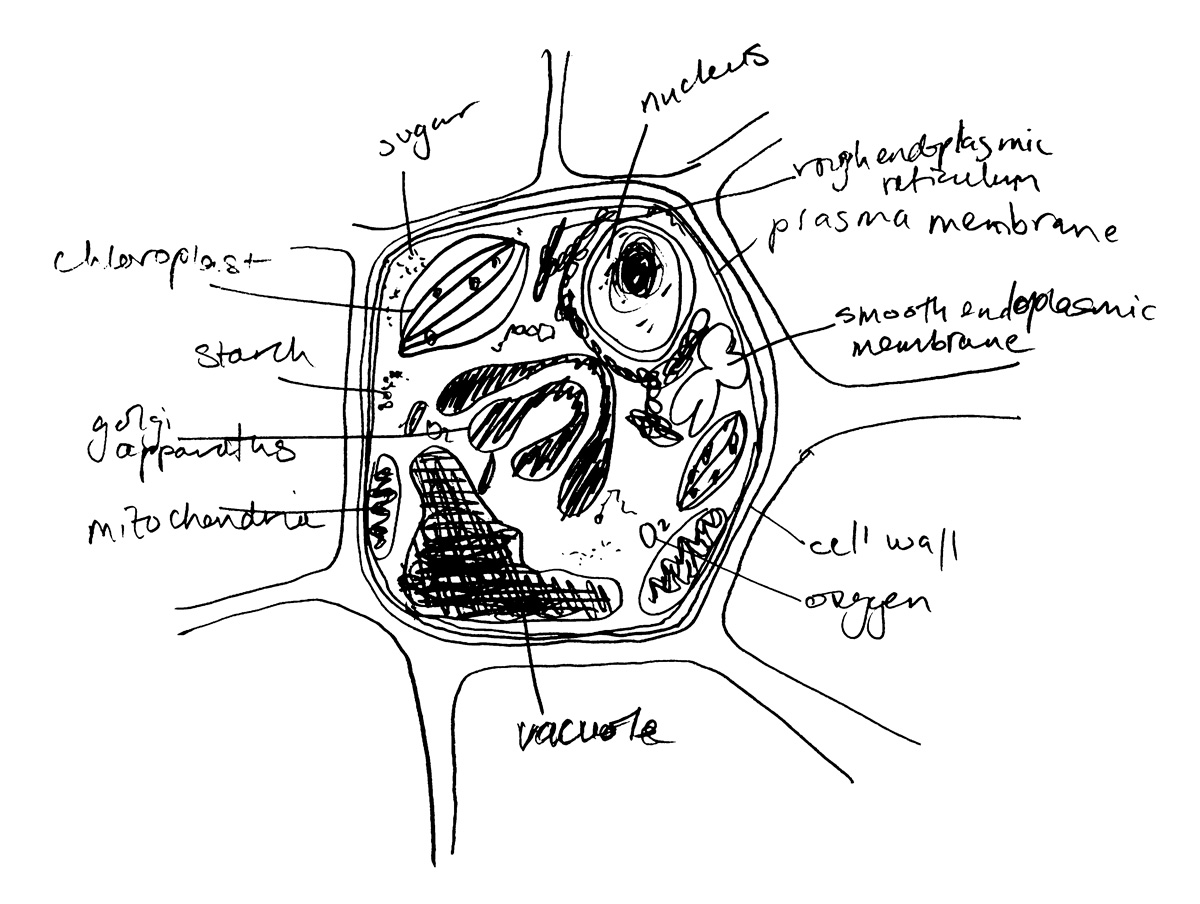

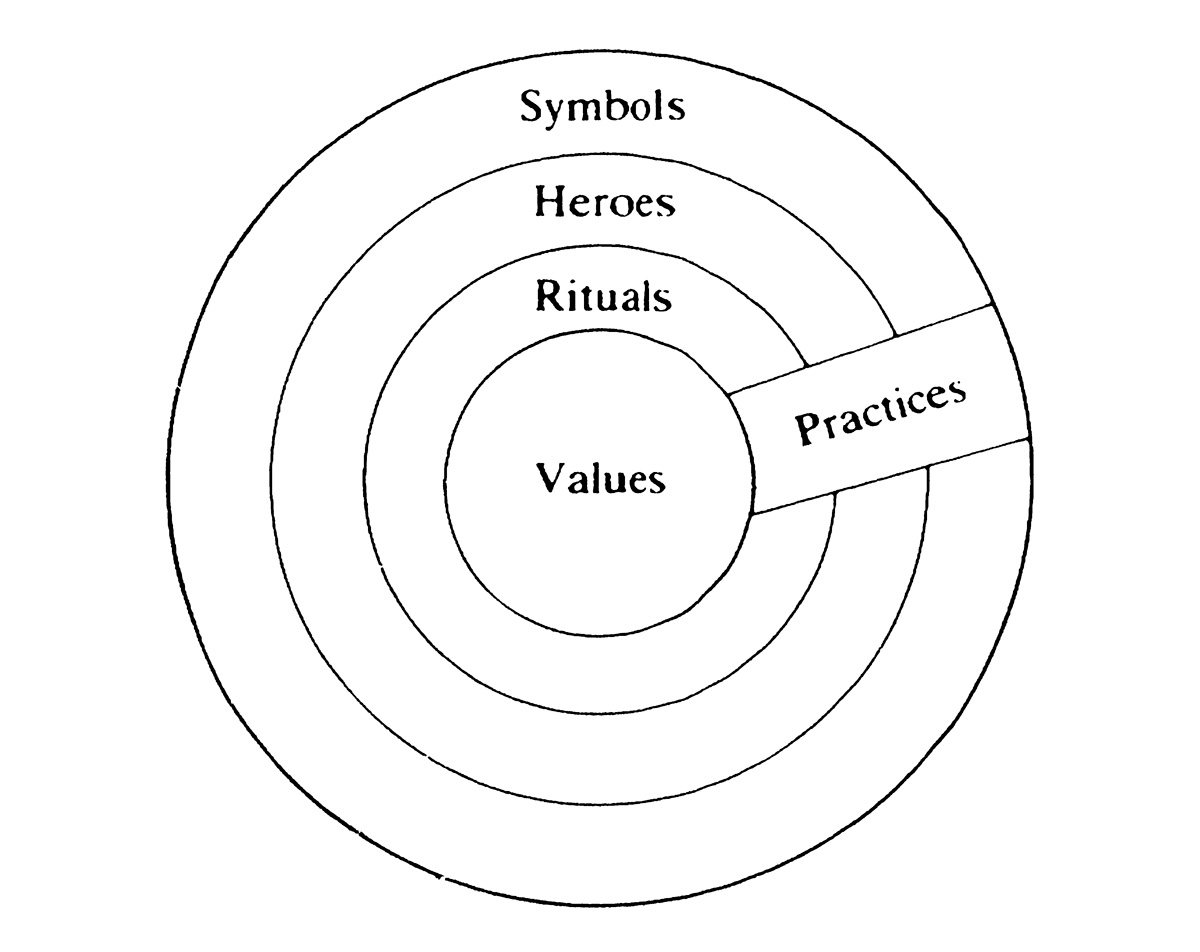

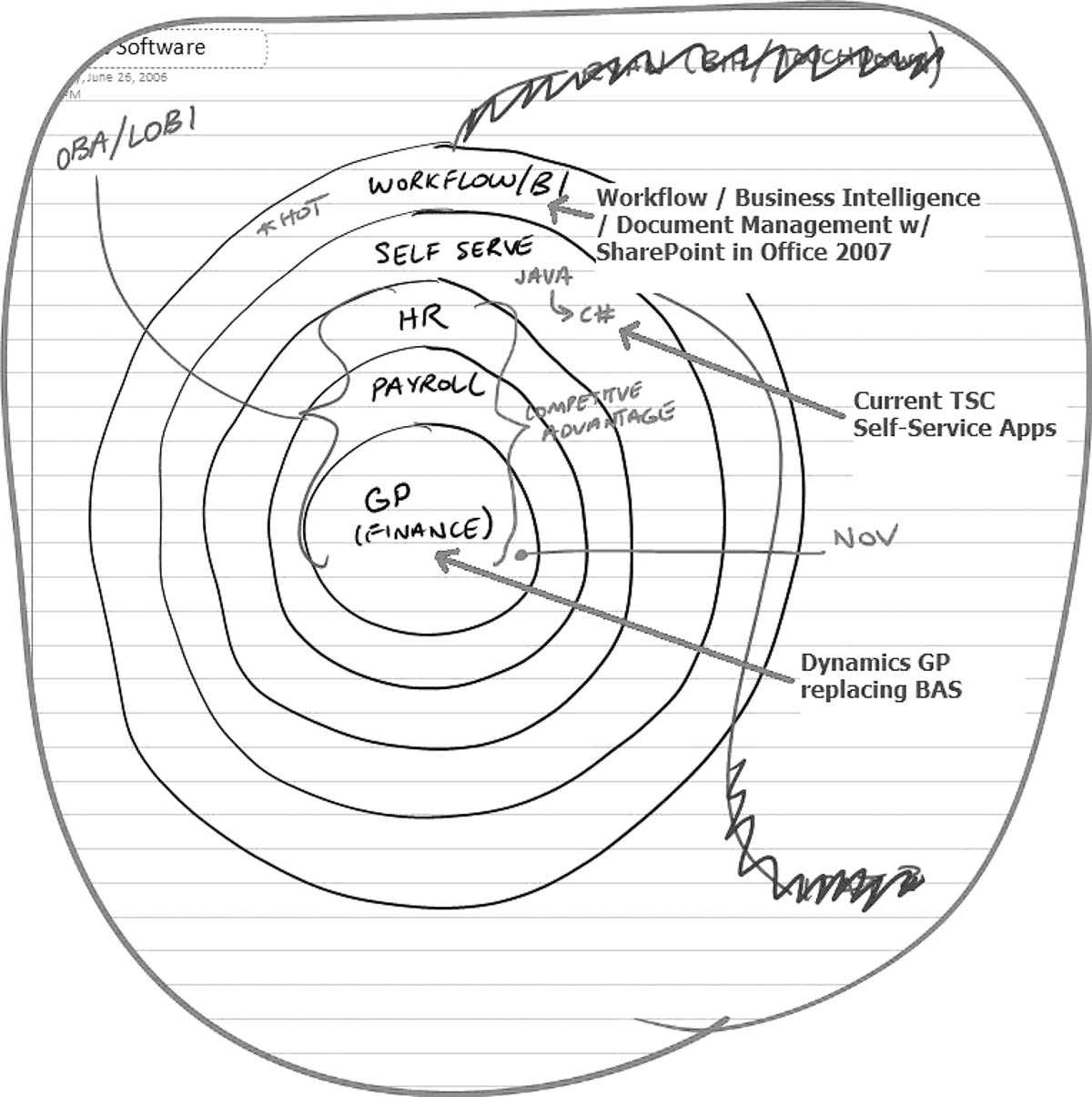

Cultural differences manifest themselves in several ways. From the many terms used to describe manifestations of culture the following four together cover the total concept rather neatly: symbols, heroes, rituals and values. In Fig. 1.2 these are illustrated as skins of an onion, indicating that symbols represent the most superficial and values the deepest manifestation of culture, with heroes and rituals in between. …

In Fig. 1.2 symbols, heroes and rituals have been subsumed under the term practices. As such, they are visible to an outside observer; their cultural meaning, however, is invisible and lies precisely and only in the way these practices are interpreted by the insiders.

The core of culture according to Fig. 1.2 is formed by values. Values are broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others. …

Development psychologists believe that by the age of 10, most children have their basic value system firmly in place, and after that age, changes are difficult to make. Because they were acquired so early in our lives, many values remain unconscious to those who hold them. Therefore they cannot be discussed, nor can they be directly observed by outsiders. They can only be inferred from the way people act under various circumstances.

—Geert Hofstede and Gert Jan Hofstede, Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind—Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival (London: Harper Collins, 1994).

The[r]e are blank pages in the back of the bible that I see no problem with smoking. They are the traditional onion paper, which roll excel[l]ent joints…

—Anonymous, “Recreational Marijuana Use,” grasscity.com discussion board entry, 19 March 2003.

When garnished with a pickled pearl onion, the Martini is known as a Gibson, endearingly called “onion soup.” There are three stories about the origins of the Gibson. One has an American ambassador named Gibson serving in London during Prohibition. He wished to make his English guests welcome with a cocktail, but personally felt constrained to follow his country’s laws even while abroad. So during receptions he would circulate a glass of water with a cocktail onion in it, while the guests would be served real gin. When someone asked his aide what the diplomat was drinking, the young man answered “a Gibson.”

Steve Zell at the Occidental Grill in San Francisco says the name came out of Chicago. “You’ll notice that Gibsons are usually served with two skewered onions. I heard that during the twenties in Chicago there were twin sisters named Gibson who loved Martinis but hated olives. Whenever they’d go out, they’d get bartenders to use two pickled onions—twins for twins.”

A more likely story is that Charles Dana Gibson, the famed illustrator and creator of the Gibson girl, dropped into The Players, his New York club, and asked the bartender, Charley Connolly, to mix him “a better Martini.” Connolly simply exchanged an onion for an olive and dubbed it the Gibson.

—Barnaby Conrad III, The Martini: An Illustrated History of an American Classic (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1995).

I told you about the walrus and me, man

You know that we’re as close as can be, man

Well here’s another clue for you all

The walrus is Paul

Standing on the cast iron shore, yeah

Lady Madonna trying to make ends meet, yeah

Looking through a glass onion

Oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah

Looking through a glass onion

I told you about the fool on the hill

I tell you, man, he’s living there still

Well here’s another place you can be

Listen to me

Fixing a hole in the ocean

Tryin’ to make a dovetail joint

Looking through a glass onion

—John Lennon and Paul McCartney, “Glass Onion,” 1968.

[“Glass Onion” by the Beatles] was linked to the “Paul is Dead” rumors. The line “The Walrus was Paul” was seen that it indicated Paul [McCartney] was dead. In some religions, the walrus symbolizes death. The term “Glass Onion” is a crude reference to a casket [with a see-through lid].

—Patrick, Conyers, GA

I hear a lot that the glass onion refers to a casket, but glass onions were also large hand blown glass bottles used aboard sailing ships to hold wine or brandy. They were round and if you tried to look through one (like a telescope), everything would look distorted. John [Lennon in “Glass Onion”] was saying that people were viewing his songs through a distorted perception because they wanted to extract a religious meaning from every song. Most Beatle[s] songs are actually far less mysterious than people suppose and John was sick of people over comp[l]icating them.

—Burt, nonya, WA

One theory is that “Glass Onion” refers to Lennon’s opinion of the yogic concept of the lotus with its layered petals (layers of consciousness to be stripped away, much like an onion, through meditation) as a bunch of transparent bull used by the Maharishi to manipulate and seduce. He’s also saying the Maharishi’s whole shtick stinks and is a crying shame. (thanks)

—ELBUSH, Greensboro, NC

—“Glass Onion by The Beatles” comments page, Songfacts.com, ca. 2007. Available at https://www.songfacts.com/facts/the-beatles/glass-onion.

GRANDPA SIMPSON: We can’t bust heads like we used to, but we have our ways. One trick is to tell ’em stories that don’t go anywhere—like the time I caught the ferry over to Shelbyville. I needed a new heel for my shoe, so, I decided to go to Morganville, which is what they called Shelbyville in those days. So, I tied an onion to my belt, which was the style at the time. Now, to take the ferry cost a nickel, and in those days, nickels had pictures of bumblebees on ’em. “Give me five bees for a quarter,” you’d say.

Now, where were we? Oh yeah—the important thing was that I had an onion on my belt, which was the style at the time. They didn’t have white onions because of the war. The only thing you could get was those big yellow ones…

—Dialogue from “Marge Gets a Job,” The Simpsons, season 4, episode 7, 1993, written by Jay Kogen and Wallace Wolodarsky, directed by Mark Kirkland.

PEER GYNT: Idiot, old fool. You’re no Emperor, you’re an onion, and I shall peel you, Peer my love. (He takes an onion and peels off layer after layer.) The outer layer’s pretty ragged, that’s the man clinging to the wreck. Here’s the traveller poor and thin, but still a faint taste of Peer Gynt. Inside here’s the man digging for gold—no juice, had it ever? The one beyond looks like a crown. Thank you, we’ll dispose of that quickly. (He peels several in one go.) Here’s a right handful, doesn’t the centre appear soon? (He peels the whole onion). No, it damn well doesn’t. Into the inner and it’s only layers, smaller and smaller. Isn’t nature a right wit? (He throws it all away.)

—Henrik Ibsen, Peer Gynt, trans. Frank McGuinness (London: Faber and Faber, 1990).

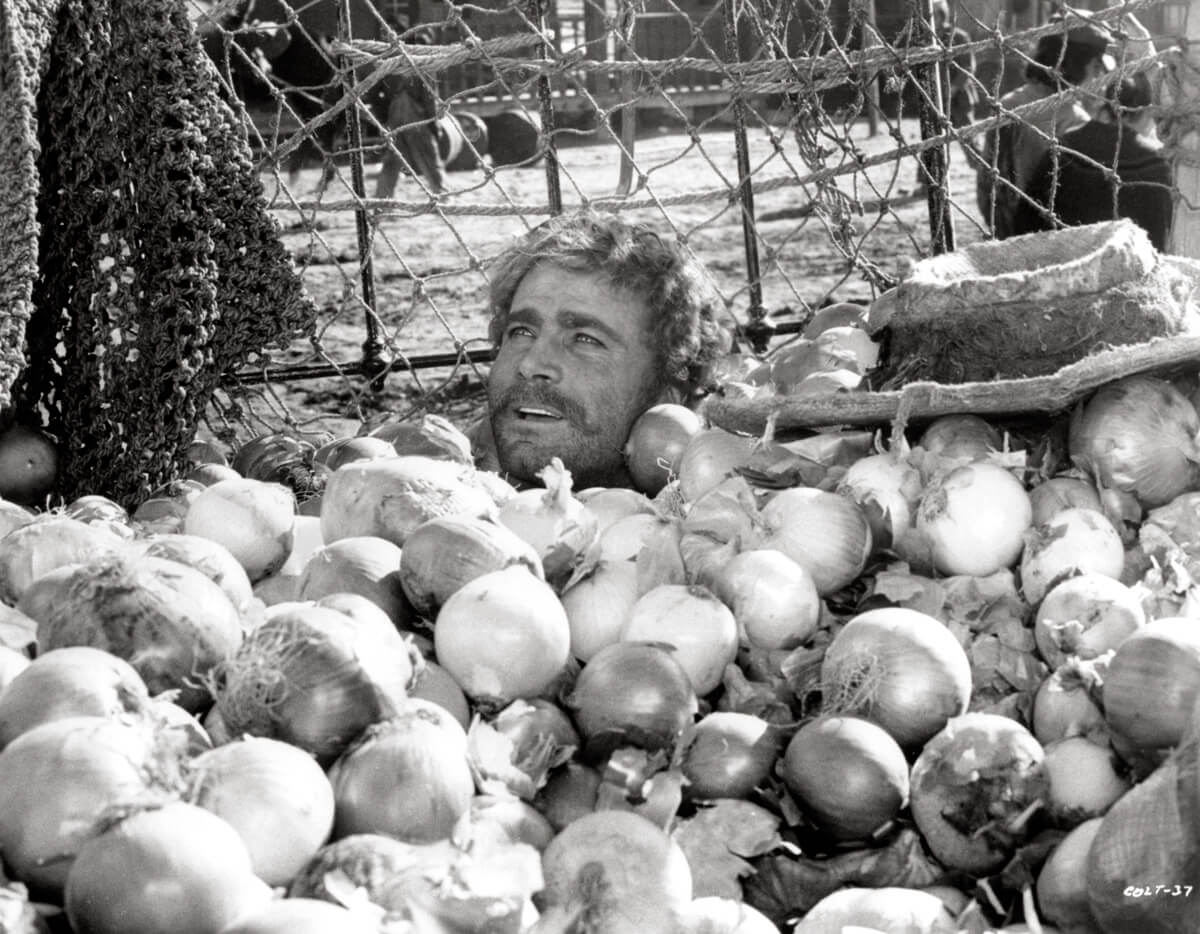

Freckle-faced Franco Nero (a gormless, onion-eating fanatic who refuses to sell a bunch of land to Balsam, an oil baron with a dart-firing mechanical hand), … spends most of the [slapstick Western] throwing onions at the baddies, or rendering them unconscious with his malodorous breath.

—[n.a.], Time Out Film Guide, ed. John Pym (London: Penguin, 2001).

The onion was another portender of weather:

“Onion’s skin very thin,

Mild winter’s coming in,

Onion’s skin thick and tough,

Coming in winter cold and rough.”

In Lancashire the onion had to be sown on St. Gregory’s Day (12th March) to ensure a good crop. Snakes dislike onions and to carry a raw onion keeps them at bay. An onion was also an anti-witch charm and a house protector but only if not cut or peeled. Raw onion rubbed on the hand deadened the pain of a blow and chilblains could be cured by rubbing with salt and onion. A roasted onion held to the ear was helpful in ear ache and in Oxfordshire a bald patch was rubbed with onion and honey to encourage the hair to grow again. Some of these protective beliefs are still in use: during the disastrous outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease on British farms in 1968, on one Cheshire farm which escaped, although in the midst of raging infection, the farmer’s wife laid rows of onions along all the windowsills and doorways of the cowsheds and attributed the farm’s escape to this. This belief seems especially associated with Cheshire for in the Rows, Chester, is an old house of 1652 with the inscription: “God’s Providence is Mind Inheritance.” The plague of the seventeenth century stopped here and the family are said to have hung a bunch of onions at their door. Sir John Harrington in The Englishman’s Doctor, 1608, recommended:

“If your hound by hap should bite his maister,

With honey, rew and onions make a plaister.”

A nineteenth-century Lincolnshire cure for toothache was to put an onion skin, like a thimble, on the big toe of the patient. Onions were used in divination. If the name of the future husband were in doubt, the initials of the possible suitors would be scratched on onions and put in the chimney corner. The first to sprout would show the husband to be. In Derbyshire on the Eve of St. Thomas (21st December) girls peeled a large red onion and stuck nine pins into it, one in the centre and the others radially. As they were inserted, the following rhyme was said:

“Good St. Thomas, do me right,

Send me my true love tonight,

In his clothes and his array,

Which he weareth every day,

That I may see him in the face,

And in my arms may him embrace.”

If the onion were placed under the pillow the charm was said to be infallible.

—Margaret Baker, Discovering the Folklore of Plants (Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications, 1971).

After failing in various plans, IAN [Saville] summons MEPHISTOPHELES (in the form of Leon Rosselson), who proposes that he buys his way into the arms industry, on payment of a certain fee:

MEPHISTOPHELES: You’ll need to look deep inside yourself to find what you need.

IAN: Look deep inside myself, eh? Well, if you don’t mind, I think that’s a very private thing to do. So, if you could all just look away … Or, on the other hand, I could use this cloth to retain my privacy. (holds up cloth) Hello in there.

VOICE BEHIND CLOTH: Hello.

IAN: Who are you?

VOICE: Don’t you recognise me?

(floats up to reveal itself as ONION-SHAPED SOUL, whose eyes light up when he speaks)

IAN: No, I can’t say I’ve ever met a floating onion before.

SOUL: It’s true we haven’t met for some time.

IAN: All right. I give up. Who are you?

SOUL: I’m your soul.

IAN: But you can’t be my soul. You’re an onion.

SOUL: Oh no. I’ve just taken the form of an onion. I’m not an actual onion.

IAN: So you can take any form, can you?

SOUL: Oh yes.

IAN: Can you take the form of a rabbit?

SOUL: Of course.

IAN: Go on then.

(SOUL makes strenuous efforts but emerges still as an onion)

IAN: That’s not a rabbit.

SOUL: Well I must have got stuck. I appear to have a small defect in my metamorphosing mechanism. It doesn’t matter.

IAN: Anyway, I don’t believe in the soul.

SOUL: That’s all right. You don’t have to believe in me.

IAN: But how can I have a conversation with you, if I don’t believe in you?

SOUL: Aha.

IAN: Aha? What do you mean, Aha?

SOUL: I’m just being enigmatic.

IAN: Well could you stop that? It’s very annoying.

SOUL: Anyway, I couldn’t care less whether you believe in me. What rankles is that you’ve neglected me.

IAN: What are you here for anyway?

SOUL: I heard you wanted to sell me.

IAN: Yes I did think about it. But I’m not going to get much for you am I?

SOUL: Why not?

IAN: Because you’re an onion, that’s why. Not a particularly valuable vegetable. And you’re defective.

SOUL: I can’t help that.

IAN: Well it’s certainly not my fault. I always suspected there was something odd about my spiritual dimension. What a thing to happen. Just when I was about to put my foot on the first rung of the ladder to success, I find I’m saddled with an unsaleable, slightly faulty soul.

SOUL: Maybe you could get me repaired.

IAN: No chance. I’m well past the warranty period. And I can’t afford the call-out charges. I understand it all now. Even my soul is worthless. I’m just one of life’s failures.

MEPHISTOPHELES: Look at it this way. There are those who succeed and those who fail. That’s the way it is. That’s the way it works. The job of government is to see that it works efficiently. To see that the right people get to the top. That’s what efficiency means. The right people getting to the top. And who, you may ask, are the right people? The right people are the ones who get to the top. That’s the way it is. That’s the way it works.

—Dialogue from Left Luggage, 1994, performed with Leon Rosselson as Look at It This Way, 1996. Written and performed by Ian Saville. Onion prop by Paul Colbeck. Courtesy Ian Saville.

“The onion is an illuminating bulb. But only by peeling its many layers, can one reveal whether it has a sweet heart or a rotten core. Suspense: thy metaphor is onion!”

The onion is used metaphorically to describe sequentially removable layers that conceal an important something. That is, when we use a metaphor involving an onion—such as “peeling away another layer”—we visualize a central concept (a heart or core) that is buried beneath an organized series of increasingly central issues or arguments. …

There is nothing of material value between each layer of a metaphorical onion: it is treated as skin upon skin, fortification upon fortification. When an “onion of a story” is formed, we beckon for that certain something that one is “hiding from us,” “not letting us in on,” “not disclosing” or “not revealing.” We will approach the matter “from another angle,” in the hopes that this will reveal underlying issues or help us gain further insight. And we may often angrily say “chaff!” when rejecting a given unwanted layer, as if an onion is a scintilla of nutritious truth surrounded by unwanted, unpalatable, irritating dross. In the onion metaphor, that which is not deemed the central truth has no lasting value. …

Unlike many fruity metaphors, the onion is not used as if bearing a central nutrition or seed of life under a simple, necessary level of protection, but rather as a series of false cores, the end of which is likely to offer a truth that is often not so palatable. While the veils of a strip-tease may necessitate a journey through undesirable layers towards the desirable beautiful core, an ugly corporate secret may be veiled away beneath layer upon layer of progressively less-beautiful mistruths. The duality of the veil is that it can both uglify the beautiful and beautify the ugly. The veil is that layer of onion—flimsy and translucent enough to beg for a deeper investigation.

The onion, then, describes the progression, rather than the destination; requiring a separate tone to distinguish the nature or value of the destination itself. It is a road—a choppy road to an uncertain, secluded destination. Whether a journey along this road results in good news or in bad news, it always results in truth, however dicey.

The onion is the stripper of metaphors—layer upon layer of mystique with no certain end. The truth is, it is the journey to the core that makes the tease.

—John D. Casnig, “The Seven Veils of the Onion,” Jaywalker, vol. 1, no. 10, January 2004.

This man was olde

And of complecyon colde

Nothynge lusty to playe

She was full ranke

And of condycyons cranke

And redy was alwaye

In Venus toyes

Was all her joys

Seldome sayde she naye

At the laste she thought

That her husbande was nought

And purposed on a daye

To shorten his lyfe

And as a true wife

She wolde it not delaye

Mayde Emlyn.

To fulfyll her lust

In a well she hym thrust

Without any fraye

And made countenaunce sad

As thoughe she be sory had

Also in good faye

A reed onyon wolde she kepe

To make her eyes wepe

In her kerchers I saye

She was then stedfast and stronge

And kepte her a wydowe veraye longe

—Anonymous, The Boke of Mayd Emlyn (London: John Skot, 1530).

A Des Moines man went to jail Wednesday afternoon for allegedly throwing an onion at his wife.

The police report begins: “[The victim] states her husband had been drinking and they got into an argument.”

James Izzolena … was charged with domestic assault causing injury. Police said he became upset with his wife, Nicole Izzolena, 27, and tossed an onion at her, striking her in the back of the head.

She told police it made her head hurt.

—Staff Report, The Des Moines Register, 20 September 2007.

Any space is not quiet it is so likely to be shiny. Darkness very dark darkness is sectional. There is a way to see in onion and surely very surely rhubarb and a tomato, surely very surely there is that seeding. A little thing in is a little thing.

—Gertrude Stein, “Mutton,” Tender Buttons: Objects, Food, Rooms (New York: Claire Marie, 1914).

“Well, you see, old Sir Roderick, who’s a loony-doctor and nothing but a loony-doctor, however much you may call him a nerve specialist, discovered that there was a modicum of insanity in my family. Nothing serious. Just one of my uncles. Used to keep rabbits in his bedroom. And the old boy came to lunch here to give me the once-over, and Jeeves arranged matters so that he went away firmly convinced that I was off my onion.”

—P. G. Wodehouse, “The Rummy Affair of Old Biffy,” Carry On, Jeeves (London: Herbert Jenkins, 1925).

One Scout goes off with half a raw onion. He lays a “scent” by rubbing the onion on gateposts, stones, tree trunks, telegraph poles, etc. The troop follows this trail blindfolded—the Scoutmaster, however, is not blindfolded, so that he may warn his boys of any danger (as when crossing roads). The Scout or patrol which arrives at the end of the trail first wins the game. The boy who lays the “scent” stays at the end of the trail till the first “scenter” arrives.

—R. S. S. Baden-Powell, “Chapter III: Tracking Games,” Scouting Games (London: C. Arthur Pearson, 1938).

The world is just a great big onion

And pain and fear are the spices that make you cry

Oh, and the only way to get rid of this great big onion

Is to plant love seeds until it dies, uh huh

—Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, “The Onion Song,” 1969.

Implicasphere is an occasional publication. Past editions include “String,” “Mice,” “Folly,” “The Nose,” “Salt & Pepper,” and “Stripes.”

For orders and information, and to give feedback, email info@implicasphere.org.uk or visit www.implicasphere.org.uk [link defunct—Eds.].

Texts have been reproduced as they appear in the original publications. Idiosyncrasies and house styles have been largely left intact. Considerable effort has been made to trace and contact copyright holders and to secure replies before publication, but this has not been possible in all instances, particularly with older material. We apologize for any inadvertent errors or omissions. If notified, the editors will endeavor to correct these at the earliest opportunity.

Implicasphere is edited by Cathy Haynes and Sally O’Reilly.

“String,” “Mice,” and “Folly” were commissioned by PEER. “The Nose” and “Salt & Pepper” were supported by the Moose Foundation for the Arts and the Elephant Trust. “Stripes” was supported by the Henry Moore Foundation and the National Lottery through Arts Council England, London.

“The Onion” is supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, London. The editors are also grateful to Cabinet (New York), The Photographers’ Gallery (London), Gerry Gilmore, Alexandra Neel, Ian Saville, and the audience for “Peeling Onions with Implicasphere” at the Photographers’ Gallery, 12 June 2007.

Designed by Fraser Muggeridge studio.

Printed in an edition of 13,000 on Cyclus Offset (recycled).

Copyright Implicasphere Ltd, London, 2007. Registered company no. 5757303.